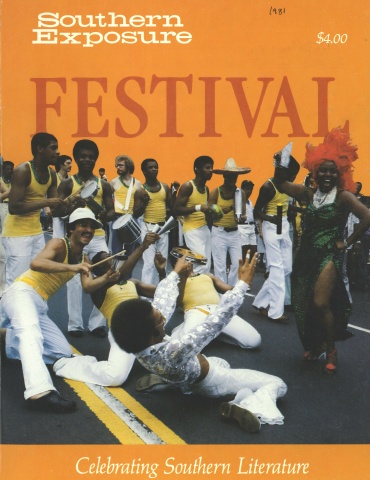

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

A feller wanted to marry this man’s daughter. Said he told the boy first he’d have to find two or three worse fools than he was. So he took off down the road and after a while passed by a bam where they was a man going in and out pushing an old empty wheelbarrow. He stood there watching a little bit and finally asked the man; said. “What you a doin?” “Well,” he said, “I got some wet hay in the barn ’n don’t want it to rot or get wet, so I’m just toting out some of that shade in there and carrying back sunshine to dry it out!”

Well, that feller allowed this’n was fool enough for one so he lit again and fore long he heard the awfullest squealing and grunting ever was, sounded like all hell was busted loose. Looked off to one side and there was a man beating the pure devil out of a young boar at the foot of a big oak tree. “Buddy, how come you’re beating that poor hog like that?” “Poor hog my eye! All that mast [acoms] up there and this damn thing’s too crazy to climb up and get it. But hit will once’t I beat him up there!” So that made number two fool. They was more to it. I reckon that feller got his girl in the end. Now her daddy - seems like the old man was a king or something. Mother used to tell it but I just can’t recollect all that tale.

The darkly complected furniture worker at the Bryhill Pacemaker plant in Lenoir, North Carolina, wiped sweat from his forehead as we faced the present reality of driving screws into the base rails that semi-circle the dressers made in our cabinet room division. In spite of the heat, behind those sparkling eyes a cool breeze of memory was blowing away the foul fumes of wood stains and the stink of hot glue and replacing the shrouded, polluted sun of today’s world with a clearer, cleaner one which shone for him once more on the fields, streams, woods and home of his childhood in the 1930s and ’40s.

They was one - mighta been the same one, I forget now - where the feller had to do so many jobs before he could marry the girl. And the king, or whoever, told him he’d have to plow this great big 40-acre field real soon, maybe by dinner or supper. Before the feller started though he took a drink the old man gave him - didn’t know they was something slipped in it to work him [loosen his bowels]. Well, pretty soon he felt it coming and seen what was going on - hadn’t much more than got started, neither. So, knowing sure he’d lose if he didn’t do something quick, he dropped his britches below his hind end, tied his galluses [suspenders] to the plow arms, squatted a little while follerin the mule, and just let her fly! He got the job done in time, too.

If there were more tales of this sort, Mr. Kirby didn’t recall them at that time. He quit his job at the plant soon afterwards and I haven’t since had the opportunity to speak with him. I hope that day’s conversation may have led him to pass these tales on to his family.

Mr. Kirby should not be thought of as one of those fleeting carriers of tradition that many academics (and other collectors of folklore) seem to be always on the lookout for, ere they all become extinct. To me he is a friend and a neighbor who, because of our close association at work and my enthusiasm for such things, was willing to share some of his personal memories of times gone by. I could perhaps have expounded to him what little I knew of the German “marchen” or mentioned that his stories bear resemblance to certain features of the Norske Folkwentyr, but to have done so would have been meaningless to him. Mr. Kirby needed no explanations about the special, age-old quality of his stories; such remarks would have served only to break the spirit and feeling of the moment, as surely as Sir Walter Scott’s printed ballad did when shown to an old woman for recognition, who upon seeing it remarked that the song would never “be sung mair.”

“Riddle to my riddle to my right,

Where was I at this time last Saturday

night?

All that time in a ivory tree

A ’looking for one but along came

three.”

Oral folk literature is subtlest has many faces. When you look at one facet of oral tradition, other sides appear, many of which are jewels — valuable not so much for their antiquity, but for the way they are conveyed by the teller and for the impressions made upon the listener. Thus, although oral traditions may not always play a great part in the sweep of a person’s everyday life, they are actual and living within that life; these traditions are offshoots of human existence and experiences, born in the deeps of time and passed on through untold generations in one form or another. Ever in a state of flux and change, these forms seem to take on new shapes but are really only variations of older models. The purist may lament the disappearance of age-old dialect and primitive patterns of speech, but I’ve yet to find myself in an area in which folktales and their kin are not expressed in ways that warm a person’s heart and soul.

Probably the greatest mistake made by researchers in collecting and assimilating oral tales is in burdening the tales with many symbolisms and interpretations that really aren’t there, and in overlooking how the tales are intimately bound up with the tellers. It’s true that for the scholar there are interpretative problems to be solved, but for most of us in the everyday business of living, these problems shouldn’t interfere with the enjoyment and absorption of stories as a natural part of life. In schools and libraries, many treatises express opinions as to origins of folk tales and how they proliferated throughout the world. These works are important as records and as models for further research, but paper cannot reproduce the sound of the spoken word, nor can it express the degree to which the tellers’ whole range of experience, their lives and innermost feelings, are tied up in their lore, and vice versa. The only truth to be found is that what remains or continues of this heritage should be taken simply for what it is, nothing more nor less. As the most illiterate backwoods storyteller alive could attest, the knottiest problems have the simplest answers. Moreover, he or she would know it is foolish to complicate such beautiful pictures with questions like: “When and where?” “Why and how?” — when the answers are: “Here and now,” “What does it differ why,” and “Like this.”

“And the giant hollered, said,

‘When ye comin back to see me,

little Nippy?’

‘Never, you son of a bitch!”’

There is a watershed in North Carolina which is one of the most sheltered areas in the Appalachians, completely encircled by high, green mountains and drained through a narrow gorge by a “clear, purling stream.” Luckily for tradition, no major railroads or other outside forces bringing swift economic and industrial changes have ever entered this region to alter the basic cultural patterns prevalent there. Here one may yet listen to lonesome strains of some of the most hauntingly beautiful love songs, or ballads, still in oral circulation. A willing ear might also hear the tale of “Little Hornet and Big Hornet,” versions of Chaucer’s “Miller’s Tale,” or the one about how little Nippy caused the giant to cut his daughter’s head off.

In a similar locale not so far away, near Beech Mountain, Stanley Hicks can tell about Boatingham the soldier, once captured by the Cherokees, and his final revenge. Sister Hattie Presnell knows the one about the pioneer woman who went out to call the cow and from a distance noticed its strange appearance and bellowings. She brought her husband to the scene, and he immediately shot the beast; upon inspection of the carcass they found it to have been neatly skinned with the body of a dead Indian, hatchet in hand, beneath.

Most of these tales are not considerable in length — that varies with the one doing the telling. Personal anecdotes, jokes, riddles, sayings, beliefs, speech and customs form the traditional storytellers’ craft, and their ability to get a tale across is a natural art. Timing and surroundings play key roles, and the individuals’ knack for spinning yarns old or new may cause them to pop in something unique to themselves at any time. Since many oral tales have roots in the dim past, they exist today mainly in corrupted forms and have often split apart into short anecdotes or mere fragments of incongruous recollection, though this isn’t always the case. The teller seldom blends the tales unless it comes naturally.

I allers thought a lot of the old

womern. She was a good person

- and truthful. She told me one

time about....

The tellers’ belief that their tales actually happened gives genuine atmosphere and a sense of reality to the listener. Throughout my lifetime until his death several years ago Isaac Hopson of Green Mountain, North Carolina, was the same as a real grandfather to me. “Paw” told me one of old Mrs. Oxentine’s tales one time about a family who came through this part of the country from some place way off. On the journey they stopped off overnight at an old house by the wayside. While the head of the family was frying a piece of ham in a skillet on the hearth, a black cat ran in and began scratching at the meat. After several attempts to chase it away, the man took a knife and cut the cat’s paw off, and found a woman’s hand with a ring on one finger lying in the pan. Paw said Mrs. Oxentine might’ve told what happened afterwards but he had forgotten anything further except he’d understood the story to have been one of her experiences or that of someone she knew in her lifetime.

Versions of tales like this are legion; whether they developed spontaneously or sprang from one source doesn’t matter, for all of them are right. What does matter is that Paw made the tale come alive for me. I can still see him in his chair, knocking ashes from a well-used pipe, and hear his resonant voice, now silent, conveying pictures in my mind through the melody of his words. And now Paw and his tales live on — though he tarries to tell them in that world over “yonder” — in the memories and lives of his children, grandchildren and me.

Under gravel I do travel, over

white oak leaves I stand

Ride a filly that never was foal-ed,

and hold the mare within my

hand.

Not everyone has had the pleasure of spending his or her life among the ridges and hollers of the Upland South, learning ways and traditions handed down through each generation — nor would everyone care to, which is as it should be. If I have overstated many points in this article it is because these things mean a great deal to me and can’t be emphasized enough, because so little is known or understood at large today about a beautiful literature of the folk that has always been with us. There is a simple but adequate classification system for our stories — there are booger tales, haint, witch, bear and pant’er tales — but this continuing legacy cannot be precisely catalogued or defined. Neither may oral literature be labeled “illiterature,” which is to say the property of the unlearned, for no one class of people, either educated or unlearned, may lay claim to exclusive use of the folk process. Mountains and other natural barriers contain no boundaries of this heritage. Outside obvious localized cultural and environmental conditions, there is an inherent sameness in all people that binds us to our past and our present, the stream of which flows with us ever onward toward the future. On the passage boats of our ancestors came the old King of so many tales. He was ever inscrutable, designing, cheating, murdering, occasionally benevolent, but always himself. Today we still see his `faces: politician, preacher or whoever, the King’s with us yet. Whether disguised in joke or elaborated on in colorful tale, the truth about the King is there. Take the trouble sometime to spend a while on the porch of some mountain home and hear him still talked about and exposed for what he always was and is, for the old King is — us! And to us belongs a literature in which life contains the knowledge of all that we have ever been, or are, or ever hope to be.

Tags

Bobby McMillon

Bobby McMillon, from Lenoir, North Carolina, is currently a folk artist-in-residence at Mitchell Community College in Statesville, North Carolina. Having learned, as a child, much of mountain culture from his relatives in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina, he is a long-time collector and performer of the songs and stories of the Southern Appalachian mountains. (1981)