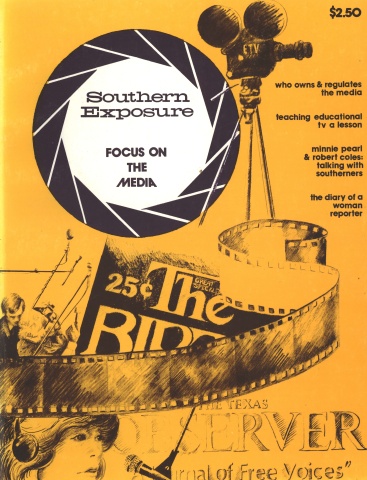

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

It has now been a good six months since the out-of-court settlement of the charges of sex discrimination brought against the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce by myself, Suzanne Anderson, Dianne Penny, Robert Coram and the Atlanta chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW). Each of us on the staff of the Chamber's Atlanta Magazine received cash settlements, the women for back pay differential, Coram for a promised raise which had not been forthcoming. Penny, Suzi and I also received raises. (Coram had resigned before the final settlement to freelance in south Georgia.)

Today, Penny is serving as caretaker of a house on Cumberland Island off the Georgia coast, rising with the sun, painting and experimenting with banners as an art form. I am a freelance writer, which is what I've wanted to be for some time. Only Suzi remains at the Magazine. She has been named art director.

The Atlanta Chamber of Commerce now has an internal task force to monitor its own employment practices, will soon come out with a new nondiscriminatory employees' manual, a single employment application for men and women which asks neither maiden name nor marital status, and a new schedule of insurance benefits with liberalized provisions for maternity costs. A standardized pay scale is now in effect.

An official of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in Atlanta stated a belief that “the influence of what you did will be felt beyond the city, beyond the state."

I listen to this statement now, sift through year-old newspaper clips, and feel strangely divorced from the whole proceeding, as though it were something done by an alter ego, while flesh-and-blood me stood by and watched. I do not disown it. I simply still cannot believe I became involved.

But my involvement was central to initiating the action. Many of the women at the Chamber had seethed under such unconscious slights as telephone memos marked "Mr. ______ called," memos from Crowder to "Staff Girls" instructing us to tidy up the offices of our (male) superiors, all female schedules for cleaning the coffee room, and telephone extension lists with columns segregated into men and women. But I was the first person among us recognized as having a clear-cut case of sex discrimination. Atlanta Magazine is the official monthly publication of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. As the Magazine's only female editorial associate (staff writer), I was making $9,600 in August, 1973, when we filed charges. Two other editorial associates, Robert Coram and Don Smith, were pulling in $13,500 and $12,000, respectively. We all did essentially the same thing —write for the magazine. I turned in my share of the "heavies," the lengthy business articles, along with the men. I had seniority over both of them, in fact over everybody except the editor and the advertising manager. Coram had more years on me as a journalist but had not completed his undergraduate degree. Smith had fewer years in the field than I but had nearly completed his Masters degree work at Georgia State University. I hold a Masters from Columbia University. Given the fact that all it takes to file a discrimination charge is the knowledge that males and females performing the same job in the same company are being paid unequally, it was clear that on whatever level the management chose to challenge me, I could field from a position of strength.

Discussion of salaries among Magazine staffers was strongly discouraged. While editor Norman Shavin had never called it a firing offense, the implication was there. For years we lived in virtual ignorance of each other's gross income. But with the advent of Smith and Coram, a strange, happy chemistry took effect. Co-workers became close friends. In an atmosphere of mutual trust and easy conviviality, a chance remark here, an aside there, and it wasn't hard to come up with $13,500, $12,000, and $9,600.

Once we put it together, the knowledge rankled.

It was in mid-July of 1973, 2 p.m., the hottest, sleepiest, least productive part of the day, when I found the copy of Ms. magazine stuck in my typewriter. Coram had left it there, circling a squib stating that the Wage and Hour Commission of the United States Department of Labor had broadened its scope to include discrimination charges from salaried professional persons as well as wage earners, and that such charges could be filed anonymously for investigation. To the page he had stapled a note: "OK, Thomas. Here it is. If you don't get in gear and do something, a lot of people will be very disappointed in you."

I've always been a pushover when it came to peer pressure, and he knew it. I picked up the magazine by a corner, gingerly, with thumb and forefinger, as if it were a dead mouse. My ears were ringing. I paused with it mid-way between trash can and desk. I laid it on the desk.

I took a deep breath. My ears were still ringing and strange things were starting to happen to my peripheral vision. Things were starting to get red around the edges. I got up, walked to Dianne Penny's office, and asked her, since she was an active member in the organization, whom I should contact in NOW for advice on filing a sex discrimination charge. She gave me the office number of a woman named Karen Over. I called her and made an appointment for lunch.

Or rather, my alter ego called Karen Over. It couldn't have been me. I have never been a boat rocker nor a maker of waves. If my life had had one guiding principle up to that moment, it was that of keeping my nose clean. I had never so much as crossed the street in support of a cause, never put a political bumper sticker on my car, never sent contributions to strange organizations that solicited through the mails. I am not sure today that I would class myself among the feminists. It has always strained my sense of the rational that any talented, productive, goal-oriented human being should be made to suffer injustices for possessing those seemingly laudatory qualities, but since I defined myself as talented, productive, goal-oriented, and a sufferer of injustices, I hardly considered myself the bearer of an impersonal standard.

None of us could have been said to possess a “radical taint." Penny's membership in Atlanta NOW and Coram's pro-union activities while a reporter on the Atlanta Journal were about as far as our collective involvement went.

Penny grew up the eldest child and only daughter of a NASA engineer working in Huntsville, Alabama. Suzi's father is a Republican businessman, owner of a chain of furniture stores in South Carolina. Coram's early south Georgia upbringing centered around his father's military career. I was raised the only child of parents who were 50 and 52 years old at my birth. My father was a retired Navy Captain-turned salesman. Most of my youth was spent in Sylvan Hills, a quiet residential Atlanta neighborhood composed about equally of blue- and white-collar workers.

With the exception of Penny, the "baby" of our foursome, we had all come to social awareness, or what then passed as a reasonable facsimile, in the Eisenhower years. It was a consciousness bounded by fall-out shelters, segregated schools, Chuck Berry and "The $64,000 Question." My own teen-age fantasies stopped at a ranch-style house with a patio, a tall, dark-suited, smiling husband, a tow-headed little boy in bluejeans with a pocketful of baseball cards and bottle caps, and a curly-haired prissy little princess of a girl, sensibly spaced two years after the boy. A "career" was something that a woman only turned to if the above didn't materialize by high school graduation. She then feigned great interest in her work to avoid hiding her head in public shame for her feminine failure. She knew, and the world knew, she would rather be home washing diapers with Cheer in a Maytag and reading McCall's, "The Magazine of Togetherness."

As a proper teen-ager of the latter Fifties, I starched my crinolines, rolled down my bobbysocks, and dutifully batted my eyes at the boys in my class, despite the fact that I was sure such conduct must be an insult to their intelligence and that they were all four inches shorter than I.

Maybe it was that fateful four inches, but I think it had more to do with the fact that nobody told me girls weren't supposed to speak up .in class with the answers. Perhaps it was something else entirely. But the ranch-style house, the smiling husband, and the ideally-spaced children eluded me. The career did not. At age 24, in 1966, by what I then viewed as an incredible series of accidents, I had become the entertainment editor of the Atlanta Constitution. It was five years later that I realized I'd got there because it was exactly where I wanted to be.

As a "woman in a man's world," it did not occur to me to do anything but take my lumps. I think it eased some of the guilt I felt for enjoying my lot so much. But they smarted, nonetheless.

Every afternoon a copy boy delivered the afternoon Atlanta Journal to every male reporter in the Constitution city room. After watching this for about three months, I asked him if I could please have a paper, since I was an editor and needed to keep up with what my Journal counterpart was writing.

"There's just enough for the men," he answered, confirming my suspicions.

"Here, Diane, you can read mine," said a nearby male reporter, fishing his Journal out of the trash can and picking a pink wad of Dentyne off the front page. I smiled and thanked him. He was really trying to be helpful. But my hands shook with fury.

Two years later, on leave of absence from the paper to take a graduate degree in theater and film criticism, I watched the student rebellion at Columbia University from the sidelines, motivated only to keep out of the way of the TV cameras, lest the folks back home see my face and think me a participant. I refused all suggestions that I should cover the events for the Constitution, fearing my reports might be interpreted as leftist by the mere fact that I was present on the scene. I sent the Constitution one feature story on an open-air campus benefit concert by the Grateful Dead.

I returned to the Constitution to find myself for some still mysterious reason no longer entertainment editor but drama critic and general assignment reporter, back about where I had started four years before. I resisted suggestions that I file a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board, fearful such a move would brand me as a trouble-maker. I simply left the newspaper six months after my return from New York and went to Atlanta Magazine. I was the first editorial associate hired by new editor Norman Shavin and for two months the only editorial associate on the staff. My starting salary in January, 1970, was $7,000.

During the following three years at the Magazine, it became increasingly difficult to swallow my lumps. When William Schemmel was hired two months after me as an editorial associate for a rumored $9,000, I was not upset. After all, I reasoned, he'd been working as a reporter longer than I had. But I resented being made to answer the office telephones two lunch-hours per month as part of a rotating pool of "girls" to relieve the two receptionists, when Schemmel was never expected to take "phone duty." I also resented having to clean up the Chamber coffee room, another "all girl" enterprise. In a couple of months, women on the Magazine's creative staff were relieved of phone duty and coffee clean-up, but the remaining lists were still all female. My problem had been solved, but the problem remained.

I stood by silently as males were given all the foreign travel assignments. When I was finally sent on a story, to Jamaica for four days, Shavin informed me that he knew of at least one other woman going from the Atlanta area, "so you'll have someone to talk to." He sounded like a concerned father, and again I felt ashamed of my anger. But the feminist movement had hit the South, and it was becoming much harder to dismiss the unintentional everyday slights as the way things were, had been, and would continue to be.

It was becoming apparent to me that most perpetrators of such slights not only were unconscious of what they were doing, but they had no idea of what "discrimination against women" even entailed — no conception of the concept, one might say. Shavin, for example, ensconced in the liberal, Democratic tradition, champion of 1960's civil rights, would surely have paled at the image of himself as oppressor.

When Penny, Suzi and I each received single red roses from Charles Crowder, executive vice president of the Chamber, along with all other female employees in honor of "National Secretaries' Week," I called Crowder, thinking to return the flower with a gentle explanation that, since my duties were not secretarial, I should really not be included in the celebration. I had some thought in the back of my mind about asking him to take stock of his female employees not simply as "the girls," but by nature of their positions, talents, etc. His secretary answered the phone.

"I wanted to talk to Charlie about the roses for 'National Secretaries' Week,'" I began. "What's the matter? Didn't you get one?" she asked, worried.

"I'll just call back later." I put down the phone feeling like the world's worst misanthrope. I did not pursue the matter. It seemed like too long a trip.

I think as much as anything it was this utter unconsciousness on the part of otherwise well-meaning people, of men in high places, able to effect changes, to chart the course and identity of the city, and of women who could see no other way than the past, that led us to charge the Chamber. I know it wasn't the money. None of us were convinced we'd get any. I doubt that it was a desire for notoriety. Neither Coram nor I have pumped the experience for the journalistic mileage we could have got from it, and Penny and Suzi aren't writers. And it certainly wasn't to enhance our professional reputations. I, for one, was almost certain the Establishment would spit us out like peach pits.

I don't know what went through Penny, Coram, or Suzi's minds as we set the first wheels spinning. I thought about the men I knew who couldn't understand why their wives were jealous of their work. I thought about the married women I had met and envied — placid, seemingly content with their ranch-style homes, smiling husbands, and ideally spaced children — and who sat in rapt and sometimes wistful attention as I talked about my life. And I thought of my friends with children, prissy, curly-haired princesses, and of the possibility that someday I might have one of my own. I would want her to be able to choose marriage as responsibly as she would any other way of life, and never, never be forced to view it as a woman's only means to the good life, a state to be rushed into with whomever as the sole avenue to economic stability and true social acceptability.

I also considered the paranoid possibility that I might never again be able to earn a decent living in Atlanta, and spent a lot of time indulging that old stand-by: fear of the unknown.

I.

Karen Over, who was serving in some sort of legal research capacity with the Atlanta chapter of NOW, advised me that Penny and Suzi might well have sex discrimination cases of their own. That was fine with me. It made things a lot less lonely. A meeting was set up with the three of us, Peg Nugent, then president of Atlanta NOW, and an attorney who had some work on NOW's behalf. There our grievances were taped. Suzi and Penny, it turned out, did each have a case. Suzi was then assistant art director and Penny was designer. Each was making less than males who had previously performed those jobs.

We decided, and I can't remember why, to work through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission rather than Wage and Hour. We would each file anonymous complaints with EEOC, and NOW would file a class action charge and negotiate on our behalf, shielding our identities. Robert Coram then decided he would also file anonymously in support of Penny, Suzi and I. So one hot early August day in 1973, the four of us visited the EEOC's Atlanta Regional Office a few blocks from the Magazine. We went at lunchtime. Practically everyone in the EEOC office was at lunch also.

"We'd like to file discrimination charges," Coram told the woman at the reception desk. She looked at the white male and three white females. "What for?" she asked incredulously. In the South, "discrimination" still meant "race."

Another woman took information from us which was filed as background on the NOW charge made by Karen Over.

The following week I was due in the hospital for a minor, if confining, operation. I had three weeks of sick leave. During my convalescence, the Chamber was notified of the anonymous complaints and the charge from NOW, and NOW president Peg Nugent called a press conference. I sat home and watched it on the six p.m. news, congratulating myself on having accidentally happened upon the perfect alibi to preserve my own anonymity. "How could I have had anything to do with it? I've been sick."

Chamber officials refused to reply to anonymous complaints. A breakfast meeting scheduled between NOW members and Chamber officials to discuss the matter turned into a fiasco when Crowder prepared to run a standard orientation film on Chamber activities and several NOW members stood up and demanded they scrap the film presentation and talk about what the Chamber was, or was not, doing for its female employees.

By December we were convinced the Chamber really wasn't going to dignify NOW's class action charge with any serious consideration as long as it was based on anonymous complaints. Two courses of action lay open. We could either come out of the closet and try to force them to negotiate, or wait perhaps two years for our case to come up in the crowded regional EEOC calendar, when our identities would doubtless become known anyway. We were beginning to feel the strain of a self-imposed isolation from other staff members. With a "well, what the hell" attitude born of frustration and anger at the ineffectuality of all we'd already done, Penny, Suzi, Coram and I filed individual charges December 13, 1973, and pre¬ pared for whatever shock waves would be forthcoming when our identities were discovered.

An eerie closeness was beginning to grow among the four of us, which went well beyond the desire for friendship. It was suddenly necessary for each of us to be aware of the others' feelings at all times, as suddenly four individual personalities were expected to come up with collective and almost instantaneous decisions. We couldn't just call meetings and go with the majority vote. Our "majority" was three. That would leave a lonely minority of one. So we thrashed out each question until we arrived at a course of action reasonably satisfactory to everyone. There were angry confrontations, tearful resolutions, late night phone calls to buoy flagging spirits, early a.m. breakfasts. We each for our own sake had to voice what we wanted, how we felt matters should proceed. We began to function almost like a therapy group.

Our attorneys met with Chamber officials, including Atlanta Magazine editor Norman Shavin and advertising manager Ronald K. Hill, to present our charges the Wednesday before Christmas. The meeting was scheduled at 4 p.m. At 3:45 p.m., Suzi, Penny, Coram and I walked into Shavin's office and closed the door. One of us, I believe it was Coram — I know it wasn't me—told him we were the charging parties and that, out of professional courtesy, we wanted to make our identities known to him before the meeting. Whoever was speaking added that none of us had intended the charges as personally directed at him. He sighed, said he had thought we were the ones, smiled a little sadly, and put on his jacket to go upstairs to the meeting. My hands were shaking so badly I tried gripping my elbows to steady them. That only made my whole torso shake.

We left the office before the meeting upstairs adjourned. I went home. I was to spend a lot of time at home alone. I had little emotional energy for social contacts that winter. None of us did. We spent time with each other.

Two days after we'd named ourselves as the conspirators (which is how we were certain we'd be thought of and were coming to regard ourselves), the annual Atlanta Magazine Long Christmas Lunch, compliments of our printers, was staged in lavish style in a private dining room at a downtown restaurant. It was more wake than party. But for some reason Suzi, Coram and I (Penny was home sick) each took advantage of this supposedly relaxed atmosphere to again stress to Shavin that our actions sheathed no personal vendettas. "I know," he said to me sadly. "But you understand that what you all have done has to be answered. There will be a confrontation, and I regret that."

& then

Two weeks later, we found out what he meant. On January 7, 1974, an afternoon meeting was scheduled in which the Chamber would formally reply to our charges. In the small conference room upstairs were gathered Crowder, Shavin, Chamber comptroller Wayne Hare, the Chamber's attorney, our attorneys, Penny, Suzi, myself, and Cynthia Hlass, newly elected president of Atlanta NOW. (Peg Nugent, at the end of her NOW presidency, had split from the organization to form her own group, the Feminist Action Alliance.) Coram had wanted to attend the meeting but was discouraged by our attorneys since he had no specific charges of his own, but was filing on our behalf.

Two days before the meeting, Shavin had solicited resumes from Penny, Suzi and me, saying they were needed for our personnel files. We complied, despite private suspicions. Our collective strategy at that point was to bend over backwards to be as cooperative as we could with the Chamber in an attempt to ease tense interpersonal relations in the office. At the meeting Shavin denigrated the quality of our work and attempted to use information on the resumes to discredit us. He didn't look at all happy about doing it. This, then, was the confrontation to which he had earlier alluded. Our attorneys sat silently. The Chamber's attorney concluded with the statement, "We feel there is no discrimination on the basis of pay for these girls."

"Women," amended Ms. Hlass.

The meeting was cut short. Crowder had to leave to prepare for the inauguration that evening of Atlanta's first black mayor, Maynard Jackson, whom the Chamber had supported. Jackson's election reaped sheaves of national publicity lauding Atlanta as one of the most forward-looking in the nation. The timing of our meeting with the Chamber seemed somehow tinged with irony.

After our confrontation with the Chamber, we retrenched. Our tactics were getting us nowhere except to undermine our own self-confidence. The atmosphere in the office was strained. And self-generated internal pressures were taking their toll on each of us.

Coram, Penny and I filed retaliation charges with EEOC, Penny and I on the basis of what happened at the meeting, Coram because a promised $1,500 raise had been cut to $500 "so that certain inequities might be corrected." Suzi, by then under consideration for promotion from assistant art director to art director of the Magazine after the resignation in October of art director Jacques Bulkens, declined to file a retaliation charge. The new charges automatically bumped our case up for earlier consideration on the EEOC roster.

Meanwhile the annual raises had been given out. My $9,600 was brought up to $11,000. I considered dropping my charge for about two hours. Suzi frowned and pursed her lips. Penny got so angry she began to cry. I quit talking about dropping my charge.

We all turned out on Saturday before the opening of the 1974 Legislative session to join in the march supporting the Equal Rights Amendment. My stomach knotted up and my hands turned cold on the steering wheel as I drove downtown, packing my head with country music from the car radio as if it were my last chance. Once on the street, I was glad I had come, yet I still shied away from cameras —an instinctive protective action, I figured.

Shortly thereafter, Suzi, Penny, Coram and I met for lunch with Ms. Hlass, Bebe Smith, Atlanta NOW vice president, and Judy Lightfoot, national NOW chairperson. NOW had decided to dismiss the attorneys and employ pressure group tactics. "We felt like both they and the Chamber were giving us the runaround," Ms. Hlass later recalled. NOW wanted to negotiate directly with Bradley Currey, president of the Trust Company of Georgia bank and the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. Any action broader than making reparations among the Chamber staff would have to come through him, NOW officers reasoned. A key demand, both from NOW and from the charging parties, was implementation of an affirmative action plan which would serve as a guide for correcting inequities not only within the Chamber staff, but in member businesses as well. NOW planned to picket the Trust Company and wanted, if not our full public support, at least assurance that we would not discredit their actions. We gave it to them, but that meeting marked the last time we were all four present and in agreement on anything. Suzi, Penny and I also dismissed the attorneys, deciding to work through the EEOC. We reasoned that, while the Chamber officials might be reluctant to negotiate through our lawyers, they could hardly refuse to cooperate with a federal agency, particularly since they had been occasional recipients of federal monies.

NOW began picketing the main Trust Company building the last week in February. The weather was perfect — sunny and unseasonably warm. For seven days from noon to 2 p.m., members marched and leafleted in Central City Park, a popular downtown noontime gathering place in front of the Trust Company building. On March 3, NOW called a press conference in the park. Ms. Hlass announced that Currey had refused to negotiate. “Seven times I called him and seven times he refused to return my call. Finally he called to say he had nothing to say," she stated. The conference made front page news, which did not look very good for an “international city" planning to host in April the Organization of American States conference, being held for the first time outside Washington, D.C. A week later, “underground sources," whose identity I still am not sure of, had arranged a meeting between Currey and NOW officials. Meanwhile, Penny, Suzi, Coram and I filed background information with the EEOC District Office for public record concerning the conditions leading us to charge the Chamber with sex discrimination. We had done all that was needed on our part to initiate a pre-decision settlement.

Currey met with NOW representatives in mid- March. "We had a basis of understanding, once we sat down face-to-face," Ms. Hlass said later. "Currey stated he was unaware of any discriminatory practices within the Chamber, but decided to investigate the matter on his own."

With providential good (or ill) timing, just when Currey began looking into the situation at the Chamber, a Magazine employee was dismissed in a quarrel resulting from her refusal to stop typing a letter and fix her male superior a cup of coffee. Currey concluded discriminatory practices existed and forthwith nominated Bob Guyton, president of the National Bank of Georgia, to put together a task force which would initiate an efficient crash program to shape the Chamber into a model employer. Priorities, as outlined by Currey, included: drafting a statement of release to the public putting the Chamber on record as strongly in favor of equal employment opportunity for women; consideration of ways the Chamber could help erase the stereotyped image of women in our society; and other ways in which the Chamber could take an active leadership role in the Atlanta business community to encourage equal opportunity for women.

Guyton's committee returned in three weeks with three goals: to establish the Chamber as a model for equal opportunity in Atlanta; to place the Chamber's personnel policies and benefits on a par with industry; and to develop a salary administration program. Said goals were to be implemented by May 31.

Meanwhile, at the end of March, I took a muchneeded week's vacation. On my return, I discovered that Robert Coram had resigned, citing mysterious "pressure tactics" from Shavin. He later admitted his sudden departure stemmed from the same internal pressures that beset us all. "I'd begun to feel like I just couldn't get up in the morning and go to that office again, but that if I didn't and didn't make it in on time, and didn't spend the whole day sweating over my typewriter, something horrible would happen. It was getting so I just couldn't write anymore," he said. It was a feeling shared by the three of us remaining.

(Coram's departure brought an immense feeling of relief to the Chamber. "With him out of the way, maybe now things will quiet down," one executive was heard to remark. Of course they would accept Coram as the instigator. He was the only man involved.)

I also discovered Crowder had resigned as executive vice president and would leave in May. Howard Benson, membership director, would function in his place until someone was selected to fill the post permanently.

When the formation of Guyton's personnel task force was announced, Penny and I sent congratulatory letters to Currey and Crowder. We also indicated we were willing to initiate informal discussion of a pre-decision settlement (which would not require full investigation by the EEOC) with Currey or whomever he designated. He designated Benson.

Suzi had decided to settle directly with the Chamber, ostensibly dropping her charge with EEOC. But Penny and I still wanted the clout of a federal agency behind us. (Although Suzi settled privately, she didn't sign the papers necessary to drop her charge through the EEOC until the rest of us did so.)

Benson, an affable, 30-year-old Chamber staffer, started off by tearing up the male/female telephone list. He then came to each of the charging parties. "We know there have been inequities and we want to see them corrected as badly as you do and as quickly as possible. Now please tell us what you want." That was late May. On July 31, the Chamber held a press conference announcing formal settlement of the charges.

"The Board of Directors of the Chamber adopted a policy of Equal Employment Opportunity at its June 12 meeting and urges its 4,000 member firms to be aware of the legal obligations

of the Equal Opportunity Act," Currey read. "From the experience of the Chamber in this area, other business and professional firms may draw on the first-hand knowledge of our organization in planning their own affirmative action and compliance programs."

It was greeted by NOW as an extremely positive statement. Guyton's task force and NOW had hammered out a mutually agreeable affirmative action plan.

As for the four of us, we each got a little less compensation than we'd dreamed of, but more than we'd expected, the mark of a favorable settlement.

Suzi was named art director, after she and Atlanta Magazine editors had conducted an extensive search to fill the post. She was awarded a cash settlement and given a substantial raise. Coram received the additional $1,000 he had been promised and denied in January. I received a $3,000 cash settlement for back pay differential and a raise to $12,000, which brought my salary in line with what the lower paid of the two male editorial associates (Smith) had been making when our charges were initiated. Penny was given a cash settlement and raise but was denied the title of assistant art director, although she had been performing the duties on an acting basis since Bulkens' departure. She remained "designer."

There were other, less tangible benefits. Shortly after Suzi's appointment as art director, she hired a male assistant who came from Playboy Books in Chicago, where he had functioned as chief designer.

"I was a little apprehensive at first," Ms. Anderson later admitted. "I was afraid Shavin might start bypassing me in making decisions, that he would prefer to talk to the male in the department. But so far that hasn't happened. He's always come to me first, as he would to any other department head."

I also noticed a subtle change within me, which manifested itself most clearly in my relationship with Shavin. Suddenly I no longer felt on the defensive, no longer felt the burden of proof for my abilities lay entirely on my shoulders and had to be renewed each time I asked for something. Suddenly I could meet Shavin, and anybody else on the staff, head-on in discussion of validity of story idea, editing changes, and other matters — something I had seen Coram and Smith do from the start in the camaraderie that often exists between men in an office but which I had always accepted as being closed to women. Perhaps Shavin had changed. Perhaps I had changed. Most likely we both had.

The day the settlement was announced to the press, I privately told Shavin I was leaving. I gave 10 weeks notice so he would have ample time to find a proper replacement. I had wanted to freelance for more than a year. I couldn't wait any longer.

"I trust this has nothing to do with anything else that has happened," Shavin said. "You've assured me it doesn't and I believe you." I hope he did. I had been telling the truth. My departure had nothing directly to do with the charges or their settlement. A few days later, Penny announced she, too, would be leaving. It was August, 1974. A year had elapsed since we had initiated the charges. It had been an emotionally draining, physically wearing experience. Penny had insomnia. I was hyperventilating. Suzi went to the doctor for a persistent rash on her forehead and was given numerous vitamins and a prescription for tranquilizers. I proceeded to block most of the events of the previous year from memory. It took a surprising amount of research to put together this account. Unfortunately I did not follow Karen Over's advice and keep a diary. None of us did. We all should have.

Atlanta Magazine has gone through a gradual reorganization. Today no two staff positions are exactly the same. While this leaves no room for internal promotion, it also safeguards against the type of situation which gave rise to our discrimination charges.

The four of us are somewhat altered by the experience. Penny has become less of an activist. Coram is more of a feminist. Suzi no longer shields her considerable executive abilities behind pretended feminine incompetence. And I am better able to stand up and express my needs and feelings without apology.

I would like to say my attitudes about men and women are greatly changed, but I don't believe they are. I still recognize my maternal instincts, as well as the little girl inside myself. And I see the men in my world as authority figures and small boys, as well as companions. I do notice one difference, however. Having once fought for my rights and won, I am far less inclined to view men as adversaries.

None of us has given much thought to whether or not we helped effect any far-reaching changes. The long, slow process is simply over. We all learned from it, as much about ourselves as about other people and the ways of power. None of us regrets the action we took. Nor would we care to relive what began so casually that sleepy August afternoon.