'Things fell into place'

Archival family images are courtesy of the Rao family. (Illustration: Wutang McDougal)

This essay is the second in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for N.C. and the South.

This essay is the second in our CAROLINADAZE series, a joint project with Common Cause North Carolina featuring the voices of young North Carolinians and their visions for a better future for N.C. and the South.

When my grandparents immigrated from Madras, India to New London, Connecticut in the late 1960s, it was so “newsworthy” the local paper wrote a story about it.

“Indian couple compare bridal customs – mealtimes confusing too,” read the headline in the Aug. 13, 1968 edition of The Day, accompanied by photographs of my grandmother grocery shopping in her sari and my grandfather working at the local hospital.

My grandparents later settled in Charleston, West Virginia, where they were one of four Indian families at the time. My grandmother adapted her Indian cooking because she was not able to buy certain spices, as there were no Indian grocery stores or restaurants nearby. Sometimes, they traveled over three hours to visit a Hindu temple in Pittsburgh.

Fast forward nearly four decades later, and I am growing up in the South with the opposite experience from my grandparents. In 2000, my family landed in Morrisville, North Carolina, a town where today, 46% of the population is Asian. Within a fifteen-minute drive, we could access three Hindu temples, and countless restaurants, grocery stores, and other institutions that kept us tied to our Indian culture.

Today, the Triangle area’s boom in its Asian American population means even more families like mine are calling North Carolina home. And research shows that Asian Americans are the fastest growing group of eligible voters in the United States – and particularly in North Carolina.

Indian Americans in North Carolina, then and now

Asian immigrants came to the U.S. in the 1800s as plantation workers, peddlers, and railroad builders. But the Asian population grew more rapidly after 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Hart-Cellar Immigration Act, the law that allowed my grandparents to enter the country.

Immigration of South Asians in North Carolina began shortly after, in 1970. By 1990, there were over 52,000 Asian and Pacific Islanders living in the U.S., according to census data compiled by UNC’s Asian American center.

Several oral history projects capture what it was like to live in North Carolina during that time as a South Asian. Chandrika Dalal, who emigrated from Gurarat, India to Pittsboro, North Carolina in 1970 and later found work as a housekeeper at UNC-Chapel Hill, told “South Asian Voices,” a book of oral histories published by the Chapel Hill Press, that she experienced everyday discrimination.

“They don’t like your skin, they don’t like your dress. If you speak in your language, they don’t like,” she said. “They don’t respect our culture or our language.”

Chavi Khanna Koneru, who was six years old when her family moved to Durham in 1989 from Oakland, California, said in an oral history interview published by Facing South that the move felt isolating. “All of a sudden I was the only brown person in my class,” she said. She didn’t find a strong South Asian community until attending college at UNC-Chapel Hill in the early 2000s.

A more significant wave of South Asians came after the high-tech boom of the 90s, according to South Asian Voices. My parents moved to Morrisville from West Virginia in 2000, because my dad got a job at a company based there. Around that time, he says, the town was small, with just a few thousand residents, and some office space and restaurants.

My dad, Steve Rao, has served on the Morrisville Town Council since 2011. I remember watching him being sworn in at the Morrisville Town Hall, on the Bible and the Bhagavad Gita, and feeling proud. But at ten years old, I didn’t realize the significance of his being elected; he was the first South Asian American elected to office in North Carolina.

Later, when I watched his interview segment in the PBS documentary “Remarkable Journey” and saw his campaign signs at the traveling Smithsonian exhibit “Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation” in the City of Raleigh Museum, I realized his election allowed his community to feel represented and paved the way for other South Asians to run for office and win.

Morrisville doubled in size between 2010 and 2015. My dad attributes the rapid growth to the Asian community, drawn to the technology companies, nearby universities, and already existing cultural institutions like temples, mosques, and gurudwaras.

In addition to the Triangle, the areas of Charlotte/Concord/Gastonia in the southwest, Greensboro/High Point/Winston-Salem in the central Piedmont and Hickory/Lenoir/Morganton in the west are other Asian hotspots in North Carolina. But there are Asian people in every county in North Carolina.

From 2012-2022, North Carolina’s Asian population grew 63%. Now, there are more than 450,000 Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the state. “Asian Indians” are the biggest group, followed by Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and Korean.

During my childhood in Morrisville, I often still felt like an “other,” facing similar discrimination and isolation that Dalal and Khanna Koneru described. Although I was born and raised in North Carolina, I didn’t feel like I belonged. Most Asian Americans I know who grew up in the South hold similar complex feelings about how those two identities intersect, as seen in Maydha Devarajan’s oral history project, “Claiming Carolina: Southern Identity and South Asians in North Carolina.”

But after seeing firsthand the growth of AAPI communities in our state over the past two decades, including my dad’s historic role in politics, and learning more Asian American history in college at UNC-Chapel Hill, I now identify as a proud North Carolinian.

Creating space for more people to feel at home in the South is important. But there’s more at stake: our growing AAPI population will be critical for the 2024 election.

A 'political game changer'

There are now over 235,000 eligible AAPI voters in North Carolina, according to AAPI Data. While that’s a far smaller number than states with larger AAPI populations, like California, Texas, or New York, it’s still enough to swing an election. In 2020, the margin of victory in N.C. between Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden was just 74,483 votes. And a local Fayetteville City Council election in 2022 was decided by only six votes.

One group working to target this population for the upcoming election is North Carolina Asian Americans Together, which Khanna Koneru founded in 2016. She left North Carolina for Washington, D.C. after finishing law school at UNC. When she returned, she found a boom in the Triangle’s diversity and, in turn, a stronger tide of progressiveness.

“I came back, and that's when it was like, ‘Oh wow, there's so many more Asian Americans. There's so many more Indian Americans,’" she said in the oral history interview. “Things sort of fell into place and it was like, ‘OK, this is home.’ And that was probably the first time in my entire life that I felt like there was a place I would call home, which is very strange to say.”

NCAAT works to unify and engage Asian American voters by educating them about the process, providing information about candidates, and translating resources into AAPI languages.

Jimmy Patel-Nguyen, NCAAT’s communications director, said North Carolina’s quick-growing Asian population is a “political game changer” in our battleground state.

My dad said the Asian American voters he talks to care the most about investment in public education and a more streamlined immigration process. Patel-Nguyen added that Asian Americans care about a wide variety of issues, like climate and economy, but priorities differ by age.

Over a quarter of all eligible AAPI voters are aged 18-29, like myself. Patel-Nguyen said young voters are more focused on issues like reproductive rights, a reduced cost of living, and making health care more affordable.

“Young people are focused on issues that are going to shape their future,” he said. “They’re a major segment of the population campaigns really can’t afford to ignore.”

This November, I’m going to be voting across the world while working from Nairobi, Kenya. It would be easy to pretend that it’s too difficult to vote from overseas, that it’s not worth the additional effort. But I know that my vote will make a difference. So I won’t hesitate to cast my ballot.

This article first appeared in the Carolina Daze Essay Series. Find more articles here.

The CAROLINADAZE Essay Series is a project of Common Cause North Carolina in partnership with Facing South. To learn more and stay in touch, please visit carolinadaze.com and sign up for Common Cause NC's newsletter. Common Cause NC is a nonpartisan grassroots organization dedicated to upholding the core values of American democracy. Learn more at www.commoncause.org/north-

Tags

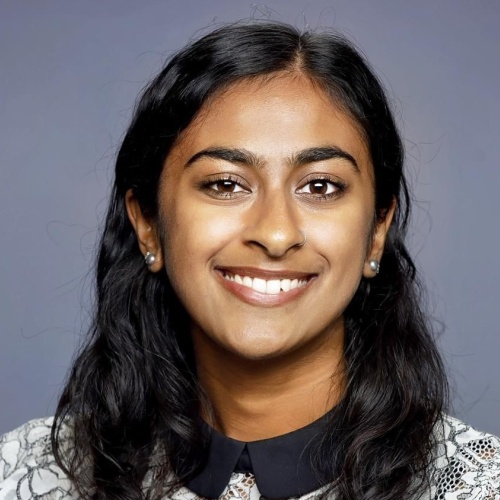

Sonia A. Rao

Sonia A. Rao is a recent graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studied journalism, history, and Hindi-Urdu. In college, she researched Asian American, Southern history while interning for UNC's Southern Oral History Program. She's written for 100 Days in Appalachia, Scalawag Magazine, Hechinger Report, and several regional newspapers.