AI disinformation poses new risks for Southern voters

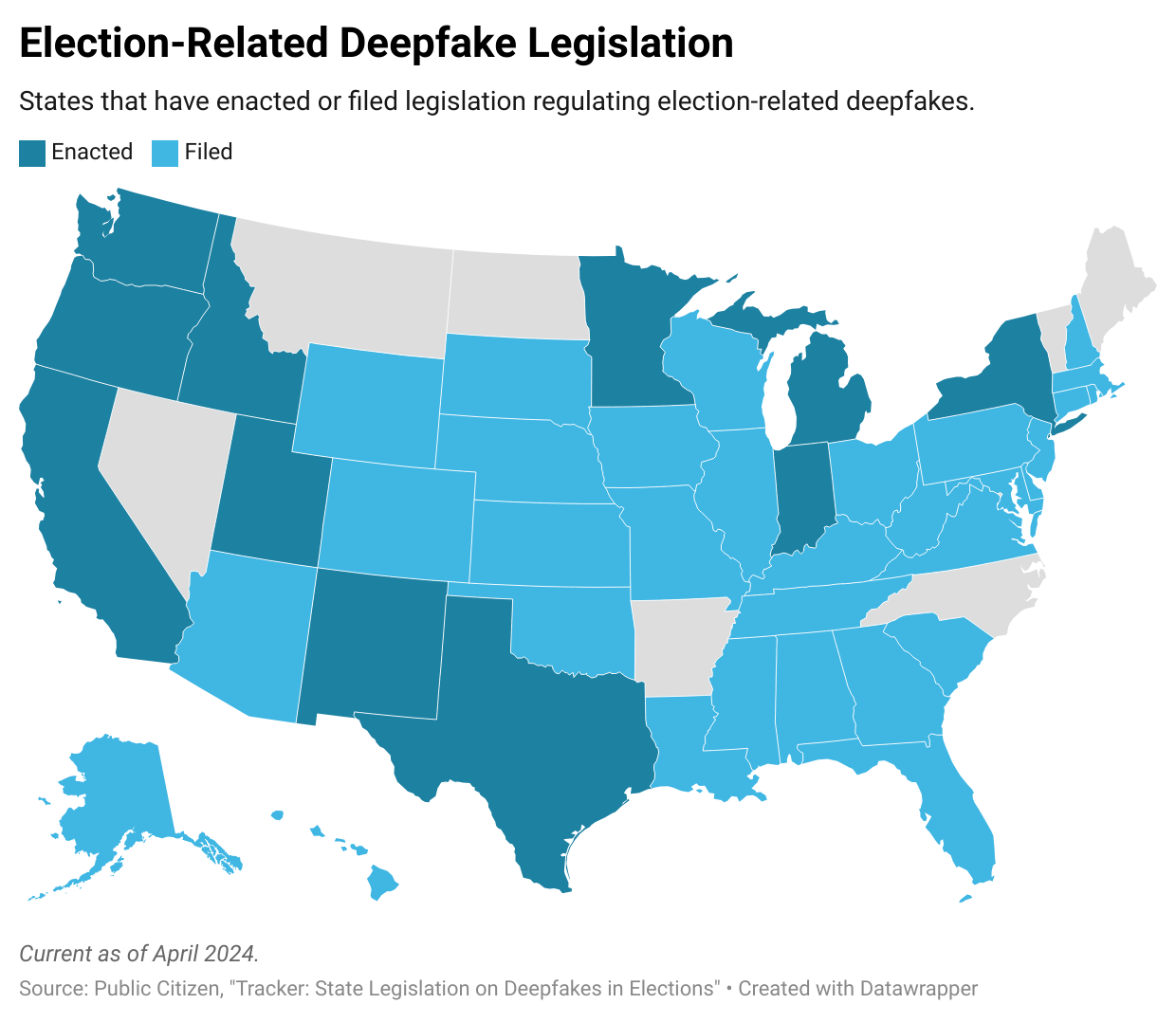

As of April 2024, 44 states have introduced bills regulating election-related deepfakes, and 12 states have enacted legislation (Map created by Caroline Fry using data from Public Citizen.)

Earlier this year, thousands of New Hampshire voters received robocalls with audio of what sounded like President Joe Biden's voice telling them to stay home during the state's primary election. But the recording wasn't really Biden: It was a “deepfake” generated with AI technology. The state's Attorney General's Office Election Law Unit ultimately identified the source of the false AI-generated recording as two Texas-based companies, Life Corporation and Lingo Telecom. In response to the incident, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) banned robocalls with AI-generated voices.

Deepfakes are fraudulent audio, video, or images created or edited with AI. As the technology becomes more accessible, advocates fear that attempts to mislead voters will become more common. "The political deepfake moment is here. Policymakers must rush to put in place protections or we're facing electoral chaos," said Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, in a statement. "The New Hampshire deepfake is a reminder of the many ways that deepfakes can sow confusion and perpetuate fraud."

In addition to swaying voters' attitudes toward candidates, AI could be used to undermine the administration of elections by spreading disinformation to curb voter turnout. The disenfranchising effects of high-tech deception will likely be compounded in the South, a region with a troubled history of election-related deception, and voters already face growing obstacles to participation.

Voter suppression rooted in disinformation is nothing new in the South, but the emergence of new technologies has the potential to add harmful burdens for already marginalized groups of voters. These suppressive efforts are increasing as communities of color have grown in political power. Right-wing lawmakers have weaponized disinformation by deploying allegations of widespread election fraud to stoke distrust in the U.S. electoral system and to sell policies that suppress the vote to their advantage. Many of these tactics have roots in Jim Crow-era efforts to disenfranchise people of color through blatant voter intimidation strategies. Policies like poll taxes mandated Black voters to pay to register to vote, and literacy tests required them to read a passage of the constitution, while "grandfather clauses" spared whites from such requirements.

New technologies historically bring more systematic attempts to suppress voters of color through “racialized disinformation” via mailing, robocalls, and other forms of mass communication. For example, in 1990, North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms's campaign sent 150,000 postcards targeting Black North Carolinians that included incorrect voting information and threatened arrests for voter fraud. More recently, in 2016, Black voters were directly targeted by Russian bots in online efforts to spread disinformation, according to a report by Deen Freelon from the University of North Carolina. The research showed that false social media accounts masked as Black users during the 2016 presidential election exploited racial tension in the United States to suppress voter turnout in Black communities.

In 2018, social media accounts published misleading voting information, including directions to vote by text and claims that voters of one party were instructed to vote the day after Election Day. During the 2020 presidential election, widespread incidents of digital disinformation occurred. For instance, on election day in Texas's presidential primary, robocalls misleadingly instructed some people that voting would occur a day later in an attempt to deceive voters into showing up at polling locations too late to cast a ballot lawfully.

With the rise of AI, voting advocates worry that the lack of effective protections against digital disinformation will influence this fall's election. "While it remains unclear how much AI will change the face of vote suppression in the 2024 general election, new developments in AI use and capabilities lend fresh urgency to long-standing efforts to abate attempts to subvert elections", wrote Mekela Panditharatne, who serves as counsel for the Brennan Center's Elections & Government Program.

Regulating AI

A flood of new legislation across the South is attempting to address the growing concerns about the ways AI can be used to influence elections. As of April, 44 states have either introduced or enacted legislation regulating election-related deepfakes. The majority of bills have been passed with bipartisan support.

In 2019, Texas became the first state to ban deepfake videos that intend to “injure a candidate or influence the result of an election” within 30 days if an election. Updates to the measure are now being considered after a recent “deepfaked” mailer paid for by the Jeff Yass-financed Club for Growth Action PAC, targeted House Speaker Dade Phelan and former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, falsely depicting the pair hugging. State lawmakers are now calling for the law to be expanded to include radio, sound, speech, and text. Earlier this year, Florida's General Assembly passed a measure mandating that political ads that include deepfake content have a disclaimer. Recently, in Alabama, the state House passed a bill that bans the distribution of deepfakes within 90 days before an election unless the content includes a disclaimer. The bill is now awaiting passage in the Senate.

Bipartisan legislation has been introduced in Congress that would ban the dissemination of false AI-generated content to influence an election, but no federal laws have been passed. Two Democrats, Sens. Amy Klobuchar (Minn.) and Chris Coons (Del.), and two Republicans, Sens. Josh Hawley (Mo.) and Susan Collins (Maine), are currently pushing legislation that would ban deceptive AI content in political ads. Recently, at a Senate subcommittee hearing titled “Oversight of AI: Election Deepfakes,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) showed how artificial intelligence can be used to subvert the democratic process. Blumenthal, who serves as the chair of the Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law, said deepfake images and videos are "disturbingly easy" for anyone to create.

In his remarks, Blumenthal referenced the New Hampshire deepfake call as a stark example of how rampant digital disinformation can interfere in elections. "That's what suppression of voter turnout looks like," he said.

Research assistance from Institute for Southern Studies program associate Caroline Fry.

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.