The deadly intersection of poverty, race, and COVID-19

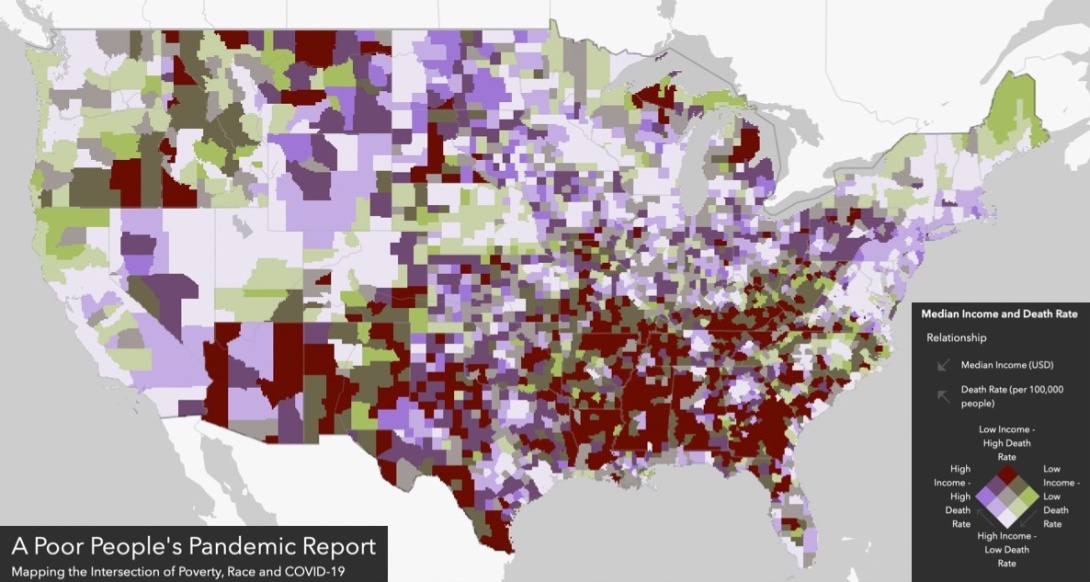

This map featured in The Poor People's Pandemic Report shows that a disproportionate number of counties with low incomes and high COVID-19 death rates are in the South.

Exactly 54 years to the day after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who was helping to lead the Poor People's Campaign at the time of his murder, the campaign carrying on his work released a report that details the disparate impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on low-income people and communities of color.

"The Poor People's Pandemic Report" was a collaboration between the Poor People's Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, Kairos Center, Repairers of the Breach, Howard University, and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), a nonprofit launched in 2012 under the auspices of the United Nations' secretary-general. In a way that no report had done previously, it maps the intersections of poverty, race, and COVID-19 — and it does so at a moment when free COVID-19 testing has ended for the uninsured and mask mandates are being lifted, likely paving the way for another surge of the illness.

The "Poor People's Pandemic Report" highlights the top 300 U.S. counties with high poverty and COVID-19 death rates. It found that rural, poor counties experienced the highest rate of cumulative COVID-19 cases. Counties with the most people living in poverty had death rates 1.5 times higher than counties with lower poverty levels. During the third phase of the pandemic in the winter of 2020-2021, death rates were 4.5 times higher in the group of counties with the lowest median income compared to those in the group with the highest median income, the report found.

"What we can't say in this report is who are the people that died," said Alainna Lynch, senior research manager at SDSN. "But what we can say is that the poorest counties grieved twice the number of deaths than the richest counties."

As the more contagious Delta variant emerged in late 2020 and early 2021, low-income counties experienced death rates five times higher than wealthier counties, while during the even more contagious Omicron variant phase that began in late 2021 low-income counties experienced death rates three times higher. More people of color were infected during the Omicron phase, possibly because of the higher risk of exposure with in-person work, transportation, and housing. Counties with more Black residents experienced higher death rates than those with fewer Black residents.

The report also points to regional disparities, noting that nearly 73% of counties with the lowest median income and 76% of those with the highest percentage of people living in poverty are located in the Southeast and Southwest. Of the 300 counties noted in the report for having high poverty and COVID-19 death rates, 236 are located in the South.

The report discusses the experience of individuals like Olivia Womack, a college student who grew up in the city of Jackson in Hinds County, Mississippi, where nearly half of all residents are poor and the COVID-19 death rate was 320 per 100,000 people. Womack lost over 20 members of her family during the pandemic, including her grandmother, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

The report notes that the current challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion stems from a Mississippi law that would ban abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy. "People will fight like hell for the unborn, but people who are living are dying," said Danyelle Holmes, an organizer with the Poor People's Campaign who's also from Hinds County.

Even before the pandemic, residents of Mississippi were dying at higher-than-average rates — in part because the state is among the 12 nationwide and eight in the South that have not expanded Medicaid, the health insurance program for low-income people, under the Affordable Care Act. Before the pandemic, nearly 360,000 Mississippians were uninsured.

"Poverty in the U.S. is its own epidemic," the report observes.

But many policy solutions that could greatly alleviate poverty have either not been passed or have been scaled back. For instance, the South is where four of the five states with the most minimum wage workers live, yet state lawmakers in the region have resisted raising the minimum wage.

More recently, the expanded Child Tax Credit under the American Rescue Plan pandemic stimulus bill proved to be successful at alleviating poverty. For example, from the time the payments to families began in July 2021 to early August, the number of U.S. adults living in households with children that reported not having enough to eat declined by one-third. However, the credit expired at the end of last year because the closely divided U.S. Senate failed to renew it as part of the Build Back Better Act, sending 3.7 million children back into poverty.

On June 18, the Poor People's Campaign will hold a Mass Poor People's and Low-Wage Workers' Assembly and March on Washington and to the Polls to call attention to the demands of the 140 million poor and low-wealth people in the U.S.

"Too often, we blame the poor for what are really systemic policy decisions that are outside their hands, decisions that are made for poor communities, but decisions they would never make themselves," said Shailly Gupta Barnes, the campaign's policy director. "Whether that's around what the minimum wage should be, who has health care or paid leave or childcare, or how much debt we owe or who has enough to eat, who has clean water … these are all policy decisions, choices.

"Policy makers decide these questions, not the people whose lives are impacted by those decisions," she continued. "And now with this data and this analysis, we can see that who died during the pandemic, especially in these worst phases, was also a policy choice."

Tags

Rebekah Barber

Rebekah is a research associate at the Institute for Southern Studies and writer for Facing South.