Will the South's state courts crack down on gerrymandering?

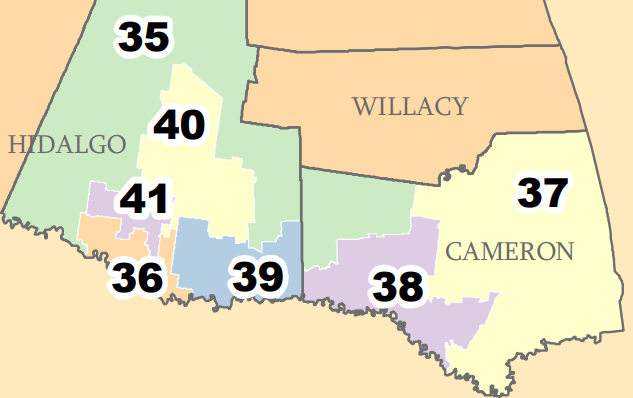

Texas' Mexican American Legislative Caucus filed a lawsuit challenging these new state House election districts for Cameron County, where more than 90% of the population is Latino. (Map from the state legislature.)

One month ago, a panel of three federal judges — including two Donald Trump appointees — ordered Alabama to redraw some of its seven newly drawn congressional districts because only one had a Black majority in a state where the population is more than a quarter Black. But the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the order in a shocking so-called "shadow docket" ruling — a break from normal procedures in which the high court issues emergency orders or decisions without oral arguments.

The Alabama case was one of several related to racial gerrymandering filed in federal court this year. While the Supreme Court struck down racially gerrymandered districts following the last round of redistricting a decade ago, it could narrow the protections of the Voting Rights Act this time around. The justices will review a recent ruling by an Arkansas judge that only the U.S. attorney general can file a racial gerrymandering suit under the VRA. If the high court upholds that decision, future administrations could refuse to enforce critical protections against racial discrimination in elections.

But while the federal courts keep delivering bad news for voting rights, advocates for voters have won some early victories in state courts. Lawsuits against gerrymandering have been filed in recent months in state courts in Kentucky, North Carolina, and Texas, and more cases could be filed in the coming weeks.

In North Carolina, voting rights advocates recently won a big victory when the state Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution prohibits partisan gerrymandering. The outcome of that case has given hope to their counterparts in other states across the South.

On Feb. 14, North Carolina's Democratic-controlled high court ruled along party lines that partisan gerrymandering violates the rights of voters under the state constitution. "We hold that our constitution's Declaration of Rights guarantees the equal power of each person's voice in our government through voting in elections that matter," the court's ruling said. "To be effective the channeling of 'political power' from the people to their representatives in government … must be done on equal terms."

The court ordered new districts that don't unfairly benefit GOP candidates. Chief Justice Paul Newby, a Republican, criticized the majority as "policymakers" who had infringed the legislature's authority; his dissent was joined by the court's two other Republican justices.

Justice Mike Morgan, a Democrat, wrote a concurring opinion that dove into the meaning of the right to "free elections" — a provision ratified in 1868 when newly enfranchised Black men helped rewrite the constitution. Morgan argued that a "free election" is one conducted "without the stain of the outcome's predetermination." Justice Anita Earls, a former voting rights attorney who sued the state over racial gerrymandering, joined in Morgan's opinion. Morgan and Earls are the court's only Black justices.

The majority ordered the North Carolina legislature to draw new maps. The court appointed a trio of former judges as "special masters" to draw alternative maps, if the court rejected the legislature's revised maps. They included former Republican Justices Bob Edmunds and Bob Orr, who left the GOP a few years ago, and former state Superior Court Judge Thomas Ross, a Democrat. Orr was on the state Supreme Court in 2002 when a GOP majority struck down districts drawn by Democrats for violating the state constitution's ban on dividing counties.

On Feb. 23, the three-judge panel that tried the case rejected lawmakers' revised congressional map, but accepted the revised districts for the state legislature. The plaintiffs appealed, and so did state House Speaker Tim Moore, who is a defendant in the case along with Senate Majority Leader Phil Berger, the father of a state Supreme Court justice. The new congressional districts had passed largely along party lines in both chambers, with experts saying they were still biased towards the GOP.

The court adopted the special masters' congressional districts, which could lead to a delegation that is nearly evenly split between the two parties. The N.C. Supreme Court declined both parties' appeals, and candidate filing has begun in the new districts.

Since the high court's ruling, Republicans have repeatedly suggested that they could re-gerrymander the districts if voters elect a GOP majority to the North Carolina Supreme Court in this November‘s election. However, the state constitution says that the boundaries for legislative elections shall be changed only once a decade. There is no such limit for congressional districts.

Politics v. constitutional rights

North Carolina's constitution isn't the only one that protects the right to vote in "free elections." Every state constitution protects an individual's right to vote. And lawsuits like the one in North Carolina are pending in a few Southern states.

In Kentucky, for example, voters backed by the Democratic Party have challenged new congressional and state House election districts that the Republican-controlled legislature approved over the veto of Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear. When he vetoed the House districts, Beshear said the map appears "designed to deprive certain communities of representation" and "dilute the voices of certain minority communities."

The lawsuit details how the state's oddly-shaped districts illustrate the legislature's intent to benefit the GOP. The congressional district map "can only be seen as an improper partisan gerrymander designed to dilute Democratic votes and make it easier for two Republican incumbents to win on their home turf," the plaintiffs argued.

The judge recently declined to order new districts before this fall's election, but the case will proceed to trial the first week of March. The lawsuit argues that the maps' partisan bias in favor of Republicans violates several provisions of the Kentucky Constitution, including the rights to free speech and "free and equal" elections. The plaintiffs also cite the Kentucky's Constitution's ban on "unnecessarily splitting counties into multiple districts," which they argue the legislature flagrantly violated.

In Texas, meanwhile, the Mexican American Legislative Caucus is arguing that new districts for state House elections violate the state constitution's ban on splitting counties. The lawsuit challenges new districts in Cameron County, where 90% of the population is Latino. The plaintiffs argue that their Republican colleagues violated the "county line rule" by splitting half of the county and putting the pieces in districts within other counties, one of which is overwhelmingly white.

The Texas Constitution prohibits the splitting of counties during redistricting unless lawmakers have a compelling reason, such as complying with the VRA. If a county‘s population is too large to have all the districts within that county, the constitution explicitly requires legislators to append the "surplus" population to another district that is within a single county.

But that's not what legislators did last year when they redrew Cameron County's districts. The county's population is too large for two districts, but instead of adding the surplus to a neighboring county's district, Republicans drew one district within Cameron County and split the remaining population between two neighboring districts in two different counties.

Some of the county's voters were drawn into a district in Willacy County, where the population is almost entirely white. Others were drawn into a district with Hidalgo County, another mostly Latino community. Before these new districts, Cameron and Hidalgo counties shared seven state House districts within their two borders.

The lawsuit, which could be headed for the all-GOP Texas Supreme Court, argues that the new districts will make it harder for voters in Cameron County to elect their preferred candidates. Jared Hockama from the county Democratic Party said the districts were "just another example of what the Republicans will do to low-income communities and communities of color in order to fulfill their political ambitions."

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.