Fighting gerrymandering in the South's Black Belt

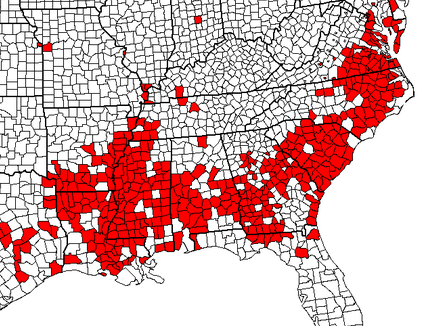

Counties in the Southern U.S. with a substantial Black population make up what's called the Black Belt. A center of Black political power, the region is now resisting being gerrymandered by Republican-controlled state legislatures. (Map based on 2000 census data is from Wikimedia Commons.)

Republican-led legislatures across the South have redrawn election districts using fresh census data, and the new maps will leave many communities of color in the Black Belt — a region of over 600 counties with large Black populations stretching from East Texas to Virginia — with less political power.

Voting rights groups are challenging the maps in state and federal court. In the previous decade federal courts struck down racially gerrymandered districts in three Southern states, but those courts now include fewer judges committed to protecting voting rights.

The lawsuits argue the new maps dilute the political power of Black communities that have elected Black Democrats to Congress. The South is growing and becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, but rural Black Belt districts that have lost significant population since the 2010 census must be redrawn. This gives Republican legislators the chance to reconfigure them to include more white voters, as they've done to districts in other parts of the South.

U.S. Rep. G. K. Butterfield, for example, saw the percentage of Black voters in his redrawn Eastern North Carolina district — long considered a "Voting Rights Act district," where voters of color can elect their candidate of choice — drop from 45% to 38%. He denounced the map as racially gerrymandered and announced that he would not run again. And in Georgia, state lawmakers eliminated the Black majority in U.S. Rep. Sanford Bishop's district in southwest Georgia, leaving it whiter and more conservative-leaning.

This year's redistricting is the first in half a century without a crucial safeguard that previously protected voters of color. In its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder ruling out of Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a provision of the VRA that required states with a history of voting discrimination to have new election districts "pre-cleared" by the federal government. However, the VRA still prohibits redistricting plans that "dilute" the political power of communities of color.

Before this year's redistricting process kicked off, three Black Belt states — Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana — were already facing racial gerrymandering lawsuits challenging congressional districts. Alabama's new districts are now the target of four federal lawsuits. More than a quarter of Alabama's population is Black, but only one of the state's seven congressional districts includes a Black majority.

And in Arkansas, the state chapter of the ACLU said the maps approved two weeks ago by the Republican-controlled state legislature "dilute the voting power of Arkansans who are also racial minorities." The group suggested that lawmakers should draw 16 majority-minority districts for state House elections, but the legislature drew only 12. Progressive groups said the new districts split up Forrest City and West Memphis, two majority-Black Mississippi Delta cities that are part of the Black Belt.

In Mississippi, where more than a third of the population is Black, Republicans have said they don't plan to make big changes to their state's four congressional districts. But the boundaries had to be tweaked to equalize the populations, and the state's sole majority-Black district contained fewer voters.

This week the Mississippi House redistricting committee passed a congressional map that every Black Democrat voted against, according to a reporter with the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. The state NAACP has recommended an alternative plan that maintained the sole Black-majority district by adding more voters in and around the capital city of Jackson. The House's proposed map instead adds a few whiter counties in the southwestern corner of the state.

The Republican-led South Carolina legislature also tweaked VRA districts in rural Black Belt counties that are losing population, after rejecting maps suggested by the state NAACP. In the new legislative maps, a state lawmaker in majority-Black Orangeburg County was "double bunked" into a district with another Black colleague. The legislature will redraw congressional districts soon.

Race blind in the Black Belt?

In North Carolina, a closely divided battleground state where the new congressional maps are expected to elect 10 Republicans to the state's 14 districts, legislators announced they wouldn't use race to redraw election districts. Democrats and voting rights advocates warned this would risk diluting Black political power and thus violate the VRA, but Republicans plowed ahead. Voting rights groups filed a lawsuit arguing that the new maps violate the state constitution by disenfranchising Black voters.

North Carolina legislators made the same "race blind" argument the last time courts struck down their election districts for racial gerrymandering — and the U.S. Supreme Court, in a nearly unanimous 2018 decision, rejected it. The justices said that lawmakers' insistence that they didn't "look at racial data" did not undermine the trial court's finding that the districts discriminated against Black voters.

Republican legislators have also claimed that, if they must draw VRA districts, they would be majority-minority districts. But that's exactly why federal courts struck down North Carolina's election districts five years ago.

In a series of cases since the 1980s, the U.S. Supreme Court laid out how states can avoid disenfranchising Black voters in the redistricting process. The process requires map makers to look at demographics and determine if it's possible to draw a VRA district. The test also involves looking at racial polarization in voting to determine how many voters of color should be in the district. If voting is very racially polarized, a majority-Black district would be necessary for Black voters to exercise political power.

If voting is less racially polarized, as in Butterfield's North Carolina district, legislators don't need to draw a majority-Black district. In fact, putting too many Black voters into VRA districts — a practice known as "packing" — is also unconstitutional. Legislators have to do the math to determine how to draw the districts fairly. In 2011, however, North Carolina lawmakers instead established an arbitrary target of "majority-minority," or 50% plus 1, for VRA districts — a process ultimately rejected by the courts.

Federal courts also struck down post-2010 election districts in Alabama and Virginia for packing in too many Black voters. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down Alabama's legislative election districts in 2015 because legislators tried to maintain the previous percentage of Black voters rather than doing the math to arrive at a fair outcome; some of the districts they drew were around 70% Black, thus diluting Black power elsewhere. The recent lawsuits in Alabama argue that the new congressional map similarly packs Black voters into one district, and they demand a second district with a substantial Black population.

It's unclear if the U.S. Supreme Court will intervene to stop racial gerrymandering in this redistricting cycle. The Court was already chipping away at the VRA before the appointment of three rightwing justices by President Donald Trump. In North Carolina and Texas, gerrymandering lawsuits have been filed in state court. Both allege violations of state constitutional rules mandating that election maps keep counties whole when possible.

The lawsuits challenging North Carolina's new legislative districts rely on a 2002 precedent in which the state Supreme Court laid out a new process for redrawing legislative election districts. In Stephenson v. Bartlett, the court's Republican majority struck down a map drawn by a Democratic-led legislature. The court ordered redrawn districts using the new process before an election could be held. The first step of the Stephenson process is to draw VRA districts, which requires map makers to look at racial demographics. But lawmakers repeatedly refused to do that.

Allison Riggs of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which is representing the plaintiffs in the racial gerrymandering lawsuits in North Carolina and other states, said the legislature's recent gerrymandering illustrates the need for a new federal voting rights law, such as the Freedom to Vote Act, to protect the political power of communities of color in the Black Belt and elsewhere.

"Our democracy is at stake," Riggs said.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.