A history of groundbreaking reporting on the South's poultry industry

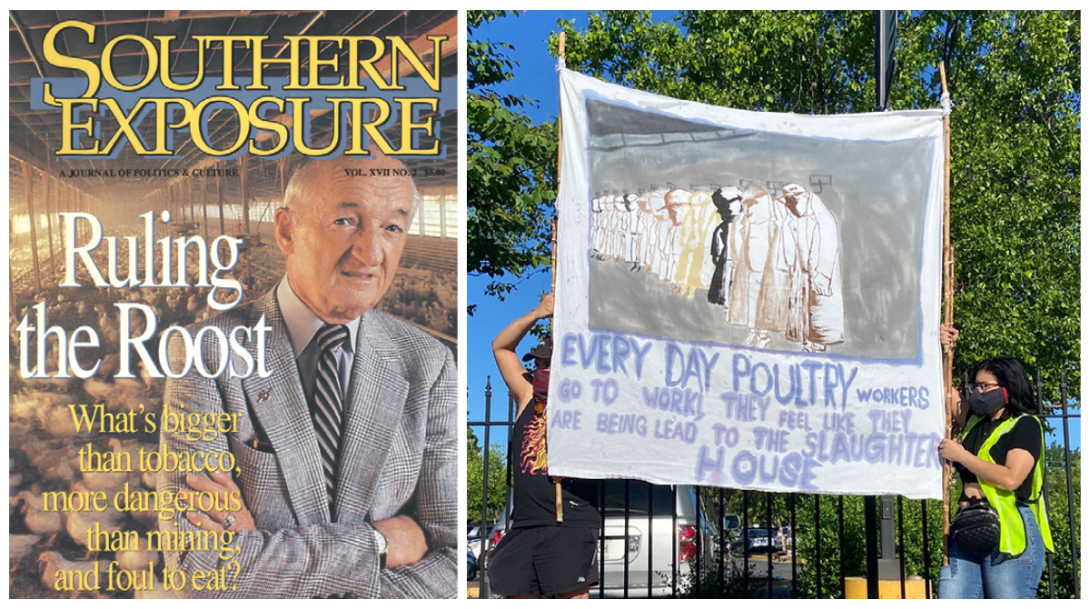

The summer 1989 issue of Southern Exposure featured in-depth investigative reporting on the South's poultry industry. At right, a sign from a 2021 protest led by workers' justice group Venceremos in front of Tyson's Berry Street plant in Springdale, Arkansas. (Photo by Olivia Paschal.)

Thirty-two years ago, Southern Exposure — the print forerunner to Facing South — set out to document the region's fast-growing and increasingly industrialized poultry industry, then in the midst of rapidly increasing vertical integration with processing companies taking control of their supply chains. The cover of the summer 1989 issue featured a photo of industry magnate Frank Perdue, wearing a business suit and posing inside a chicken house. The headline was "Ruling the Roost: What's bigger than tobacco, more dangerous than mining, and foul to eat?"

The cover section, co-edited by Eric Bates and Bob Hall, featured six stories and an infographic detailing problems related to the poultry industry — particularly how it was failing slaughterhouse workers, farmers, and consumers. It won the National Magazine Award for public interest journalism in 1990. Bates went on to serve as investigative editor at Mother Jones, executive editor of Rolling Stone, and now works as an editor at Insider; in 1992 Hall won a MacArthur Foundation "genius grant" for his research and reporting and later founded Democracy North Carolina, retiring as its executive director in 2018.

As I revisited "Ruling the Roost" over the last year while reporting "Poultry and Pandemic," our investigative series on COVID-19's impact on the South's poultry processing workforce, I found time and time again that many of the problems Southern Exposure pointed to three decades ago remained. Wages are low in an industry that remains largely non-unionized. Workers report similar grueling conditions, similar health problems, and similar fears of retaliation now as they did then. Worker safety advocates say federal safety regulators are still too lax.

One thing that has changed is the demographic makeup of the South's poultry workforce — but the industry still relies on people with little economic or political power to produce the meat that earns it billions of dollars a year.

Steve Striffler, anthropologist and author of "Chicken: The Dangerous Transformation of America's Favorite Food," emphasized this last summer when I interviewed him while reporting on the pandemic's brutal toll on the poultry workforce in Northwest Arkansas.

"They just continually seek out the most vulnerable labor force they can find," he said.

The U.S. poultry industry is still concentrated in the South. The country's five largest poultry processing states, by number of workers, are in the region — Georgia with 31,950, Arkansas with 29,014, North Carolina with 22,441, Alabama with 21,697, and Mississippi with 16,036. The same five Southern states produce the most broiler chickens in the country; that distinguishes the poultry industry from other meats, which are mostly processed in the Midwest, where workers are more likely to be unionized. The most unionized of the top five poultry states is Alabama, where 8.7% of workers in all sectors — not just poultry — belong to unions. The least unionized is North Carolina, at 3.9%. The national average is nearly 11%.

Nationwide, the poultry processing industry employed about 150,000 workers in 1989; it employs more than 230,000 today. And demand is higher than ever: While the average American ate 56.7 pounds of chicken per year in 1988, this year that number is expected to reach 98 pounds.

Some of the industry characteristics described by Hall's 1989 article Southern Exposure story "Chicken Empires" are even more pronounced now. For one thing, the industry is more concentrated. In 1989, the eight biggest poultry companies controlled more than half of the industry's sales. Today, according to Food and Power, four companies control more than half of the U.S. chicken market: Pilgrim's Pride, owned by Brazilian company JBS; Tyson, based in Arkansas; Perdue, based in Maryland; and Sanderson Farms, based in Mississippi. While Southern Exposure reported there were about 48 chicken companies in 1989, there are only about 30 today, according to the National Chicken Council, an industry lobbying group. Several — including Tyson, Pilgrim's Pride, and George's, another Arkansas-based company — are at the center of a major Justice Department price-fixing investigation that's already resulted in the indictments of several company executives.

There have been some improvements in workplace safety, but the industry remains a dangerous place to work. In her 1989 Southern Exposure story "Inside the Slaughterhouse," Barbara Goldoftas reported that poultry processing workers were at increased risk of repetitive motion injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome, which can be debilitating. That is still true today. The reported injury rate of poultry workers in 1986, 18.5 per 100 workers, significantly declined to 4.2 per 100 workers by 2016, but it still far outpaces other industries, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics — and the actual rate may have been artificially depressed by OSHA rule changes pushed by Bush labor solicitor and Trump labor secretary Eugene Scalia. A 2016 Government Accountability Office report acknowledged that injuries in the industry are likely underreported, noting the dangers posed by repetitive motion, heavy machinery, chemical exposure, and potential biological hazards.

In 1989, Southern Exposure reported line speeds had increased to "as many as 90 [birds] per minute," noting that as lines sped up and the process became increasingly automated workers "become mere appendages to the machines, performing one or two discrete motions over and over." In 2014, the legal maximum line speed was set at 140 birds per minute. In 2019, the United States Department of Agriculture's Food Safety and Inspection Service began issuing some plants waivers allowing an increase of line speeds up to 175 birds per minute. And in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, USDA approved these waivers for 15 plants— including many in the South that went on to experience severe COVID-19 outbreaks.

The power that some of the largest corporations in the world hold over the workers whose livelihoods they control has not changed over the last 30 years.

The industry's problems around bathroom breaks have also proved persistent. A worker in Goldoftas's 1989 piece recalled seeing a colleague urinate on herself on the line in the early 1980s. "She was too scared to move," the worker remembered. In the 2016 Oxfam report "Lives on the Line," a worker recalls an almost identical scene: "The supervisor said, 'Sorry, lady, but no one can cover for you. Hold it awhile more.' … Finally the woman wet her pants."

In Arkansas, home to more than 12% of all poultry processing workers nationwide, the now-defunct Northwest Arkansas Workers Justice Center pushed for state legislation addressing worker safety, but it went nowhere. "Nobody wanted to do it. My guess is the poultry industry has influence over a lot of elected officials," Fernando Garcia, then an organizer with the group, told me for a story I wrote for Scalawag magazine in 2018. Indeed, Tyson has given nearly half a million dollars to state-level politics in Arkansas since 2012, including donations to ballot measure campaigns, political parties, and specific candidates.

The poultry industry's demographics have changed dramatically over the past three decades. In 1989, poultry was women's work — primarily Black women in the Deep South. But that began to change in the 1990s and 2000s as the poultry industry began hiring immigrants from Latin America and recruiting people from outside the U.S. mainland.

"They paid my flight, 30 days in a hotel near the plant, they gave me a car and money to buy food," one person recruited to work in an Arkansas poultry processing facility from Puerto Rico told me last year. "They paid all that for one month."

It's a common practice for poultry companies looking to attract cheap labor to keep production costs low. The average wage for slaughterhouse workers nationwide is $14.79 an hour, an annual wage of just $30,760. In the Southern states where the poultry industry is most concentrated, it's even lower — around $12 to $13 an hour. Many of the workers we spoke to over the course of our reporting have worked for poultry companies for more than a decade and make hourly wages under $14 an hour.

"I have heard that an annual salary to live is $40,000, and I don't even make it to $32,000," a worker on the deboning line at George's told us in Spanish.

While the exact demographics of the poultry industry's workforce are difficult to pinpoint, a September analysis from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) found that the poultry processing workforce in the top five poultry processing states is roughly 37% Black and 26.5% Latinx. About a third of the poultry processing workforce is foreign-born, according to EPI. Among these workers, 71% speak Spanish as their first language. Workers who speak other languages — such as Vietnamese, Indigenous Mayan languages, or Marshallese — often struggle to access health and safety information, as Lorena Quiroz-Lewis, an organizer in rural Mississippi, told me earlier this year.

"You have Indigenous people that fled horrible circumstances [in Guatemala] and they come and they're working, and they're working, and they're working," she said. "How do you create something so difficult for people to understand?"

The global COVID-19 pandemic that struck the U.S. last year exposed poultry workers, their families, and their communities to new dangers. An ongoing count of COVID-19 cases in the nationwide meatpacking workforce, including poultry, since the start of the pandemic kept by Leah Douglas at the Food and Environment Reporting Network currently stands at 58,779. At least 296 meatpacking workers have died of COVID-19. The real count is likely far higher.

Our reporting over the last year drilled down into these outbreaks, and discovered that the industry's long pattern of sweeping health and safety concerns to the side in favor of keeping production running continued into the pandemic. In Arkansas, we discovered months of emails from workers, community members, and the Marshallese consul general that made the scale of the outbreaks in Northwest Arkansas's poultry plants clear long before a team from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found poultry plants at the heart of a cluster of infections in the region's Hispanic and Marshallese communities. In Gainesville, Georgia, known as the "poultry capital of the world," Sandy Smith-Nonini found in her reporting for Facing South that poultry plants sometimes appeared to seed outbreaks and in many cases contributed to the spread of the virus. In both cases, neither local governments nor the companies themselves took strong measures to stop outbreaks.

"You look at the money poultry brings into Georgia — this is strictly political," Edgar Fields, president of the Southeast Council for the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, told me at the time.

It certainly was in Arkansas. In the summer of 2020, the mayor of Springdale — home to multiple chicken processing facilities and the corporate headquarters of Tyson and George's — worked with Tyson to play down the role of poultry processing plants in spreading COVID-19 in videos posted to the company's website, even as workers, their families, and worker safety advocates raised the alarm about workplace conditions that forced them to remain shoulder-to-shoulder on the processing line.

We also discovered a Tyson spokesperson smearing local worker safety advocate Magaly Licolli of the workers justice group Venceremos in an email to the Springdale mayor, calling her a "radical union organizer" who "will just shout and make baseless accusations."

In the South, as in much of the country, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was almost entirely absent during the pandemic. Under the Trump administration, the agency did not release a temporary emergency standard, instead issuing non-binding safety "guidance" and making clear that it would cite only those companies that it had determined failed to act "in good faith."

As of January 2021, it had issued citations to just five meatpacking companies, totaling just $69,953 in fines. Just two of the cited companies are in the South, and none is a poultry company.

When the Biden administration took office, worker safety advocates were hopeful that its talk about safety improvements would change working conditions for the poultry workforce. Early on, Biden ordered OSHA to decide whether a temporary emergency standard was necessary, and if so to issue it by March 15 — but that has yet to materialize. The House Coronavirus Subcommittee, chaired by Democratic Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, is looking into meatpacking companies' actions during the pandemic but has yet to produce a report.

In some of the South's poultry plants, the pandemic has led to a burst of organizing. We reported on a worker walkout — characterized by some as a wildcat strike — in protest of conditions at a non-unionized George's plant in Springdale, Arkansas, in December; it was the first such labor action ever by poultry workers in that part of the state. Workers' centers and immigrant rights organizations from Arkansas to Mississippi to Alabama to Georgia are building power and coalitions between the many diverse groups who work side by side in poultry factories every day.

For vulnerable workers in the right-to-work South, organizing and speaking out often come at a cost. The power that some of the largest corporations in the world hold over the workers whose livelihoods they control has not changed over the last 30 years.

"They are afraid, because these are their only jobs," said Magaly Licolli, an organizer and the co-founder of Venceremos, in an interview published alongside this essay. "But they also understand that jobs are not about losing their lives. And that's why they were organizing."

Fear — and how to overcome it — was also a theme of Bob Hall's 1989 Southern Exposure interview with former North Carolina poultry worker-turned-organizer Donna Bazemore. "You feel so limited, so afraid," she said. "One way to deal with that fear is to share stories."

Tags

Olivia Paschal

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and a Ph.D candidate in history at the University of Virginia. She was a staff reporter with Facing South for two years and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South's year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also led the Institute's project to digitize the Southern Exposure archive.