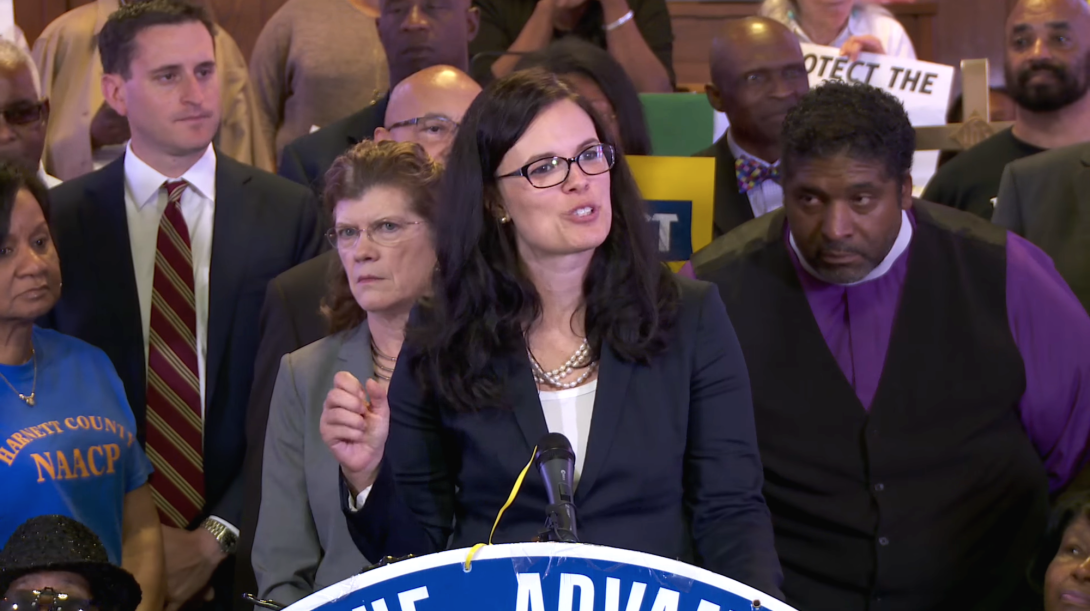

Voting rights attorney Allison Riggs on fighting for an inclusive democracy

Attorney Allison Riggs with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice spoke at a press conference hosted by the North Carolina NAACP and other advocacy groups after oral arguments in a case challenging North Carolina's restrictive 2013 voting law were heard in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Virginia. (Image is a still from this video.)

According to data from the Brennan Center for Justice, there have been 361 voter suppression bills filed in state legislatures this session, including in the Southern states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. The proposals would implement stricter voter ID requirements, limit absentee voting, make voter registration more difficult, and allow aggressive voter roll purges.

Facing South recently spoke with attorney Allison Riggs, who successfully argued against North Carolina's far-reaching 2013 voter suppression law in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The law was introduced at the legislature and passed shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court effectively struck down Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act in its ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, the landmark case out of Alabama that ended federal pre-clearance of election changes in states with a history of voter discrimination. We discussed her experience challenging restrictive voting policies in court and the fight to strengthen democracy by expanding access to the ballot box.

Riggs is the co-executive director and chief counsel for voting rights at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice in Durham, North Carolina. Her work over the last decade has focused on creating fair redistricting plans, combating voter suppression, and promoting electoral reforms that would expand access to voting. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

* * *

Can you talk about your experience of challenging North Carolina's 2013 voter suppression bill?

We got the Shelby decision in June. As you can imagine, it was a terrible blow. That very same day, Sen. Tom Apodaca, head of the Senate Rules Committee, was out in the press. There's a video of him celebrating the loss of Section 5, federal civil rights legislation that has meant the difference between political representation or not for communities of color, existentially such an important part of our history. He was celebrating that and said, "Well, now we're going to go with the full bill." House Bill 589 had been introduced early that year and was just a voter ID bill. I don't mean to suggest that it was not terrible, but it was just a voter ID bill.

There had been other bills and other efforts over the years, but it was very disconcerting for him to say the "full bill." We knew that those were ominous words, and those ominous words were followed by an omnibus elections bill.

It was incredibly upsetting. Obviously, it passed, and it rolled back every voting rights reform that had been enacted in the previous 15, 16 years: same-day registration, expanded early voting and extended early voting, out-of-precinct provisional voting, pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds. All of these were reforms that had really expanded access to the political process in North Carolina and finally acted to close the gap in registration and turnout between Black and white voters. It drove all of that back in one fell swoop.

We filed the lawsuit. I was representing a set of plaintiffs — the League of Women Voters, the A. Philip Randolph Institute, Common Cause, and the NAACP, which filed another lawsuit. We all filed the day Gov. Pat McCrory signed the bill. Then the Department of Justice entered the case. But we knew that the elections of 2013 and 2014 were on the line. We did what we could to move the case as quickly as possible, but it was a big case because it was a big law. So we had a preliminary injunction hearing in the summer of 2014 and we did the best we could to marshal the resources in short order. The preliminary injunction was denied, so we had to go to the 4th Circuit on a super expedited review.

I argued that case in late August or early September, and we won. The 4th Circuit entered an injunction and, several weeks later, the U.S. Supreme Court on the eve of the election stayed that injunction. So it was a year straight of just an incredible amount of work that the 4th Circuit recognized, and the Supreme Court yanked that out from under us. The 2014 election went forward and we didn't have same-day registration and we didn't have out-of-precinct voting.

And there were thousands of voters disenfranchised in 2014 because of that. There were thousands of voters who went to vote during early voting and weren't registered so they couldn't vote because they didn't have same-day registration. There were thousands of voters who had their ballots tossed because they were in the wrong precinct.

Then we had a three-week trial in 2015. The trial court, I think, took eight months to rule. They ruled against us in April of 2016. We again expedited our review to the 4th Circuit. I argued that case in June and July of 2016. The 4th Circuit reversed the trial court and said the North Carolina legislature had acted with near "surgical precision" to undermine Black political participation.

Then there was an attempt to get another stay from the Supreme Court. Justice Scalia had passed and a replacement hadn't been seated, but the stay was denied. So in 2016 we had a great general election, at least insofar as the rules of the election. Then in May of 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court denied cert in the case. That means they didn't take it up, which was a huge victory in and of itself.

You mentioned the loss of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. How important did Section 2 prohibiting voting practices that discriminate on the basis of race, color, or membership in a language minority group become in voting rights litigation moving forward?

We litigated the case against House Bill 589 as violating Section 2 and violating the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution because it was intentionally racially discriminatory. Normally, courts will rule under a statute before they'll rule under the Constitution, because they won't reach the constitutional claims if they can rule on the statutory claim. It was a bit unusual — and I think it was unusual because House Bill 589 was so atrocious — that the 4th Circuit didn't address the Section 2 claims, the effect claims. They addressed the institutional discrimination claims.

But we did litigate it as a Section 2 case. We litigate Section 2 cases particularly in the vote denial context, so in voter ID law or in cuts to early voting, as opposed to redistricting, which is called a vote dilution case. We did rely heavily on Section 2; it was the main tool. A lot of the evidence you'd develop to litigate a Section 2 case is the same evidence you'd use to prove the intentional discrimination case. But it took us years to build that evidence and millions of dollars. But it was critical.

Now, the Brnovich arguments heard last month in the U.S. Supreme Court [in a case out of Arizona] are about whether Section 2 is viable in the vote denial setting. Chief Justice Roberts said the reason we didn't need Section 5 anymore was because we had Section 2. And now just a few years later, they're essentially talking about gutting Section 2. It feels like a bait and switch. The tools that we do have left are important and powerful tools.

How was your successful challenge to North Carolina's voter suppression law helped by the organizing of advocacy groups?

The advocacy community did a great job of documenting publicly and for the legislature the disparate racial impact that House Bill 589 would have. Sen. [Josh] Stein [now North Carolina's attorney general] displayed data on the dashboard of the Senate that advocacy groups had given him. Sen. Angela Bryant talked about the effect that different provisions would have on Black voters. This was data that we collectively, as a democracy space, pulled together to ensure that this story was being told.

Part of why litigation takes so long is there are always discovery disputes, like what one side is entitled to find out from the other side. We engaged in these extensive discovery disputes and ultimately got documents that the legislature didn't want to give, including documents from the legislature asking the UNC system how many of their students have IDs and to break it down by race. Then they excluded student IDs [from the list of acceptable IDs for voting]. So we had that data, and that was part of why we were so successful. The advocacy groups pulled together, and that all became part of the record.

We are seeing an onslaught of attacks on voting rights across the country and especially in the South. What legal strategies or insights would you offer to lawyers and advocates preparing to challenge these bills in court?

The federal judiciary has become an increasingly hostile place for race-based claims, despite all evidence that they're meritorious, in the last four or five years. So it's a little bit hard for me to say. I continue to personally subscribe to a belief that I'm going to keep using Section 2 as a voting rights tool until the Supreme Court tells me I can't. I believe in it, and I believe in using it.

There may be some places where state courts may be a slightly more hospitable place to raise those claims. In a lot of states they interpret the equal protection clauses in their constitution a little bit more protectively than the Supreme Court has interpreted the 14th Amendment. So there may be some due process claims. I've found over the years that when judges land on due process of law they may be a little bit less ideological.

There isn't one set strategy. There is an obvious and common theme between these voter suppression laws, but voting rights litigation always has to be based from a locally intense appraisal of what the challenged law means for protected voters in that state.

You could imagine a situation where you have absentee voting but no Black voters use it at all. So if that state were to repeal absentee voting it wouldn't have a harmful impact on Black voters. It might have a harmful impact on white voters, but it wouldn't have a harmful impact on Black voters.

In the neighboring state you can have a very different situation, where the local data may show you that Black voters or Latinx voters overwhelmingly rely on absentee voting. So repealing absentee voting there could give rise to a Section 2 claim.

I find that folks who are critical of the Voting Rights Act tend to paint it with broad brushes, and practitioners who actually use it are the ones who are like, "You look at this case by case. We look at the facts on the ground and we bring meritorious cases." So that may not be the most satisfying answer, but I think it's important because the safety of Section 2 depends on the careful application of it.

Georgia Republicans recently passed a voting bill that has been compared to North Carolina's, and voting advocates have already sued. What are you expecting from North Carolina lawmakers in regards to new voter suppression proposals?

They already have a couple of them filed. One has got some startling similarities to Georgia's; it's a bill that also prohibits private money being used for election administration. But the reason for that was because Congress and almost every state failed to do what they needed to do to appropriate money for election administration in a pandemic. So in places like Georgia and North Carolina some private companies were like, "Here, we'll give counties money to buy single-use pens."

I believe it's the government's duty to pay for elections and to fund good election administration. But I can't in those circumstances fault counties that said, "Well, we need to have disposable pens. We need someone to give us some money to buy some pens so that we won't have to continue disinfecting pens that could potentially spread the virus and cause backups where voters have to wait for hours."

Georgia's law would outlaw that. The Senate bill currently moving through the legislature in North Carolina would outlaw that. Georgia's restrictions on absentee voting look a little bit different, but the bill here in North Carolina would require absentee ballots to be received by 5 p.m. on Election Day to be counted. That would make North Carolina an extreme outlier. Almost no other state does that.

It would essentially mean you couldn't use the U.S. Postal Service at all. Right now you just need to have it postmarked by Election Day. The U.S. Postal Service can't guarantee delivery, so you just couldn't bank on it. It essentially means you have to go in person. You either have to vote in person, or you have to drive to drop off your absentee ballot, which defeats the whole purpose of it to begin with.

Then they want to make the deadline for requesting absentee ballots a whole week earlier than it is now. I mean, last year there were tens of thousands of voters who requested absentee ballots in the last week before the deadline. Democracy North Carolina estimates that if those rules were in effect in 2020, we'd be looking at somewhere in the neighborhood of 24,000 to 25,000 absentee votes being thrown away and not counted. Almost half of them would have been from voters of color.

Then we also have the refiling of a bill that the governor vetoed last session that would use jury summons data to purge alleged non-citizens from the voter rolls. The governor vetoed it because jury summons data is bad and outdated. Folks in North Carolina are naturalizing quickly, at a rate of 14,000 people a year. The data from jury summons can be very old. So there is a huge risk of purging eligible voters, and it's a ton of work for county officials and election officials when there are no significant identifiable problems.

We're seeing a bunch of different bills and the legislative session isn't done. I tell folks, "This is bad already. I think it's going to get worse."

Have voting rights lawyers started to think about how they will respond to these bills if they pass?

I think right now my perspective is I'm going to keep telling folks in the legislature, until the bill is ratified, there are opportunities to stop it and to listen to your better angels and do better and be better. We're very focused on speaking truth to power and doing continual analytics. These bills change through the legislative process, and we plan on being very aggressive in that legislative monitoring and providing data to the legislature. And if litigation has to ensue, I think we'll have done what we needed to have done.

What is your hope for the future of voting rights in North Carolina and across the country?

I've been doing this work here in North Carolina for 12 years and in Florida before that. I've always thought it's important not only to fight voter suppression but to proactively paint a picture of what we think an inclusive democracy looks like, and not based on what the political climate is. I hear people say, "Oh well, it's just a messaging bill, right? Because it stands no chance of passing." But I think that's unnecessarily pejorative. We need to be more than just naysayers. We have a voice and we have agency and we can say, "This is what a truly inclusive democracy looks like."

From a community organizer perspective — I'm a community lawyer driven by community organizers — it is spiritually and emotionally devastating to always be on the defensive, to always be reacting and fighting against something rather than to hold something out and say, "This is what we stand for." I don't care if the votes are there, but there should be a minimum of early voting. There should be access to online and automatic registration for every American. That's important to me. It's important to the folks that I've worked with over my career. We as the movement can walk and chew gum at the same time. I think it's important that we do both.

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.