Southern legislatures want new courts to rule on challenges to state laws

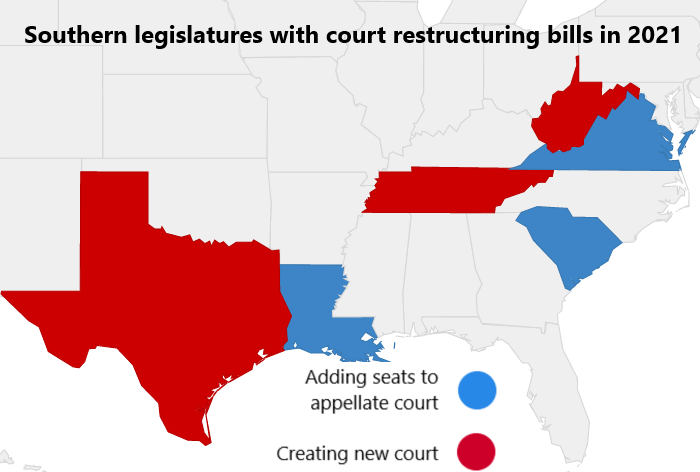

Legislatures in three Southern states have considered bills to expand appellate courts, and three others have debated the formation of new courts. Map by Facing South. Sources linked below.

Republican legislators in Tennessee and Texas are trying to create new courts to rule on lawsuits that challenge the bills they pass. These new courts, as well as a court recently created by West Virginia's GOP-controlled legislature, would likely be staffed by Republican judges, either elected in partisan races or appointed by a Republican governor.

In Tennessee, Republicans legislators have said they don't like it when local judges in the state capitol of Nashville strike down their laws as unconstitutional, so they've introduced a bill to create a new court specifically to hold trials in cases challenging state laws. In Texas and West Virginia, legislators have been less explicit about their motives for creating two new appellate courts. But their moves are part of a pattern — in those states and nationwide — of GOP politicians restructuring courts or changing how judges are chosen for partisan advantage.

Tennessee state Sen. Mike Bell (R), who represents a rural district in the eastern part of the state, is the primary sponsor of legislation to create the court. He was explicit about his political motives. "Why should judges who are elected by the most liberal constituency in the state … be the ones deciding cases that affect the state in general?" he asked. "I want judges that reflect the political makeup of the state." The proposal has already passed the state House and is now being considered in the Senate.

As an example of the kind of rulings he objects to, Bell cited a decision last year by Judge Ellen Hobbs Lyle requiring the state to relax strict rules on mail-in voting during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In late February, the state Senate considered a bill to remove Lyle because of the ruling, but the measure died in subcommittee. Pastor Earle Fisher, who leads a voting rights group in Memphis, called the legislature's threatened impeachment "another arm on the octopus of voter suppression."

Tennessee's new court would initially be staffed by three judges appointed by Gov. Bill Lee, a Republican. Starting in 2022, the judges would run in the state's first partisan statewide judicial races. The court would hold trials in the central, eastern, and western regions, including in the cities of Nashville and Knoxville. But its only western seat would be in a rural county instead of Memphis, the state's second-biggest city and the only one that's majority Black.

In Texas, after Democrats made inroads in recent appellate court elections, Republican legislators proposed a consolidation of the state's 14 appellate courts, some of which have overlapping jurisdiction. Anthony Gutierrez of Common Cause Texas said the new courts would include more Republican judges and could violate the Voting Rights Act.

But after the consolidation bill stalled, Republican legislators proposed a backup plan that would instead create a 15th appellate court to hear a range of appeals, mostly civil cases and lawsuits that challenge state laws or government action.

Currently, most cases challenging Texas laws are appealed to the court in Austin, the state capitol and a university community with mostly Democratic voters. But the new court would be chosen in statewide partisan elections, where Republicans still dominate. Critics warned that elections to the new court could see millions of dollars in campaign cash. High court races in Texas — where legal insiders have described judicial campaign giving as a "cultural phenomenon" — are dominated by large donations from corporations and corporate lawyers.

The Republican-controlled Texas legislature has been proposing big changes to the state judiciary ever since a diverse slate of Democratic candidates swept elections for courts in the Houston area in 2018. Their first proposal in early 2019 would have ended judicial elections in favor of an appointment system — but only in the state's large urban counties.

More seats to fill for WV governor

In West Virginia as in Tennessee, the move to create a new court also followed a judicial impeachment effort. But in West Virginia, it's moved beyond the proposal stage to reality.

In 2018, West Virginia's Republican-controlled legislature impeached the entire state Supreme Court, leading two justices to resign. But a temporary high court that heard the case due to the justices' inherent conflict of interest ruled the impeachment proceedings unconstitutional.

In response, the legislature earlier this year approved a constitutional amendment for the 2022 ballot that would overturn the temporary high court's ruling. It would also prohibit courts from intervening in the impeachment of any state official. Critics warn that, if voters approve the amendment, courts couldn't stop the impeachment of an official even on discriminatory grounds, such as sexual orientation.

In addition, the West Virginia legislature recently passed a law creating a new appellate court that will have the authority to overturn jury verdicts around the state. Gov. Jim Justice (R) — the owner of a coal company — signed it into law on April 10. Under the plan, the governor will appoint three judges to the new court, and they will later run in nonpartisan elections.

The head of the West Virginia Association for Justice, a group of lawyers who represent injured people, called the new court "an unnecessary expansion of our state government that will cost taxpayers millions every year." But the court has long been a priority for the state Chamber of Commerce, which spent big in recent elections to support the justices appointed by the governor, who owns a coal company.

Still in his first term in office, Justice has left a big mark on the state's judiciary, having also appointed three out of five justices on the West Virginia Supreme Court.

More diversity on the bench?

Meanwhile, some Southern legislatures are considering bills to expand appellate courts, and the new seats could be filled with judges who would bring greater demographic diversity to the bench. A recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice found that 22 state supreme courts, including five in the South, have no justices of color, while five high courts in the South include only one woman.

Virginia's Democratic-controlled legislature recently approved along party lines an expansion of the state Court of Appeals by six seats, from 11 to 17 judges. The legislature chooses judges in the state, and the six appointments could lead to groundbreaking diversity on its appellate courts, which now include only one judge of color and three women. The state NAACP and allied organizations are already calling on the legislature to consider diversity when filling the new seats.

In South Carolina, the only state besides Virginia where legislators choose judges, Republicans introduced a constitutional amendment in January to add two seats to the state Supreme Court. Democrats proposed the same change several times in previous decades, but since 2013 the push has come from Republicans. The amendment has been stalled in committee since January.

South Carolina's population is 27% Black, but its appellate courts have only two Black judges. Black legislators have pushed — unsuccessfully so far — for more diverse appointments, and they are likely to continue to do so if the legislature expands the court.

And in Louisiana, a bipartisan bill would add two seats to the state Supreme Court and require the legislature to update the districts every 10 years after the census. At least one of the new districts will likely be drawn in a way that allows Black voters to elect their preferred candidate.

In 2019, the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law filed a lawsuit arguing that the current high court election districts violate the Voting Rights Act and the U.S. Constitution by discriminating against Black voters. Even though nearly one-third of the state's population is Black, only one district out of seven included enough Black voters to elect their candidate of choice.

If the legislature creates a new majority-Black district, the lawsuit would be moot. Justice Piper Griffin, the court's only Black member, was elected last year in the district that previously elected Chief Justice Bernette Johnson, the first Black person to head the court.

The creation of Griffin's district was the result of a Voting Rights Act lawsuit in the 1990s. In that case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the VRA applied to judicial elections, and lawmakers agreed to stop splitting up Black voters in New Orleans.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.