Making sense of the chaotic West Virginia Supreme Court impeachment

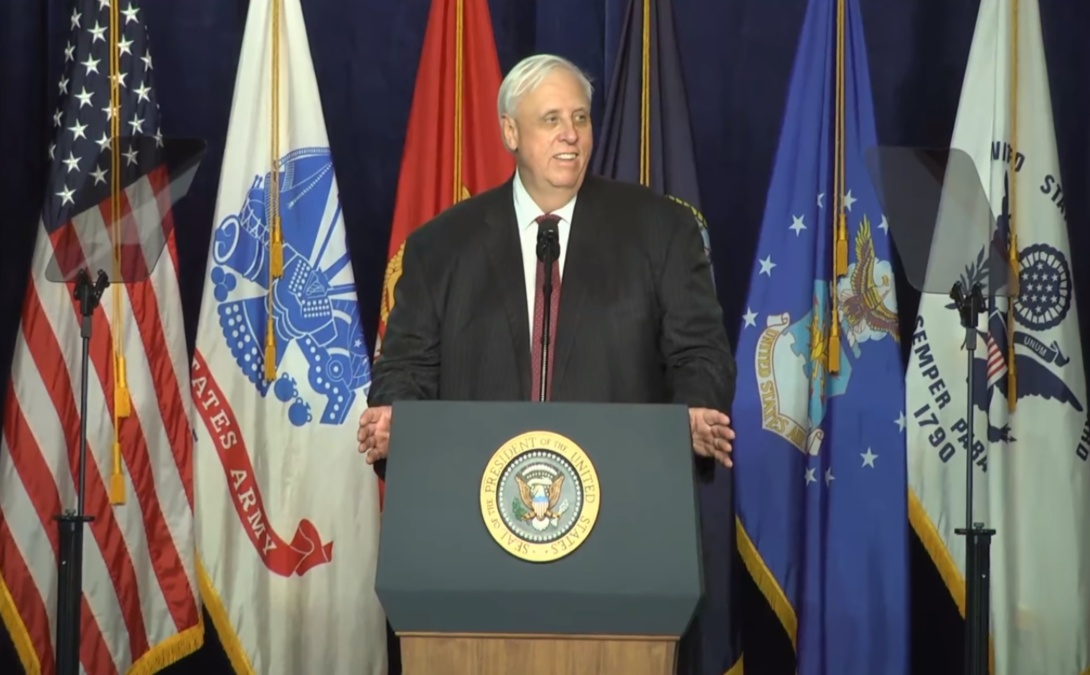

West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice, who announced he was switching his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican at a 2016 Trump rally, introduces the president at a July 3, 2018 event in his state. If the justices are impeached by the state Senate, the governor could have the opportunity to appoint a majority of the state Supreme Court. (Image of Justice is a still from this video.)

For the second time this year, a state legislature is contemplating the impeachment of an entire state supreme court: The West Virginia Supreme Court faces trial next week in the Republican-controlled state Senate.

The impeachment charges — which include lavish spending on renovations and excessive salaries for semi-retired judges — are sure to anger legislators who grappled with an $11 million budget shortfall last year. The most serious allegations involve Republican Justice Allen Loughry, who in addition to overspending and taking home office furniture was charged with lying to federal investigators.

Ironically enough, Loughry penned a book about political corruption in the state, in which he wrote, "Of all the criminal politicians in West Virginia, the group that shatters the confidence of the people the most is a corrupt judiciary."

As news spread of the justices' spending spree, legislators toured the court on Aug. 7. House leaders surprised their Democratic colleagues the next day by announcing that they would vote on impeaching not just Loughry but the entire court.

Before two justices recently resigned, a majority of the justices were Democrats. Though West Virginia switched to nonpartisan judicial elections in 2016, most of the justices were elected in partisan races. While Democratic lawmakers have said the case for Loughry's impeachment was clear, some believe the charges related to overspending are not impeachable.

So how did Republican lawmakers come to embrace such an extreme action?

The proceedings in West Virginia are playing out against a broader trend of conservative politicians targeting judges who rule against them. Pennsylvania's GOP-controlled legislature also considered impeaching the entire state Supreme Court this year for striking down a gerrymandered election map. In North Carolina, Republican leaders have lashed out at the courts for the same reason, passed laws changing how judges are chosen, and threatened impeachment. Meanwhile, President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have questioned the very legitimacy of federal judges who ruled against them.

Amid this national atmosphere of judicial intimidation, the West Virginia court's spending scandal presented Republican legislative leaders with an opportunity for radical change.

Democratic Justice Menus Ketchum left the court on July 11, a few weeks before pleading guilty to a federal fraud charge. Justice Robin Davis, also a Democrat, retired this week after the state House voted to bring impeachment charges. She did so in time to let voters choose her successor rather than having Republican Gov. Jim Justice — a billionaire whose coal companies have a history of worker safety violations — appoint her replacement in case of impeachment.

Democratic legislators accused Republican leaders of intentionally delaying impeachment proceedings until after the Aug. 14 deadline for having voters choose new justices in this year's election. If the three remaining justices are removed now, the governor would appoint replacements to serve until 2020.

Big Money shaped the court

Long before this latest scandal, the West Virginia Supreme Court was targeted by conservative special interests seeking to influence its makeup. That spending itself has led to ethics problems, such as when coal mogul Don Blankenship spent $3 million in 2004 to unseat a member of the court and elect Justice Brent Benjamin, who went on to vote to overturn a $50 million verdict against Blankenship's company. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately overturned that decision due to the glaring conflict of interest.

The controversy over Blankenship's money led legislators to establish a public financing program for judicial elections. However, that program was challenged in 2016, when the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC) dumped millions of dollars into a West Virginia Supreme Court election. The RSLC, the state Chamber of Commerce, and other big business interests spent millions to defeat Justice Benjamin — whose re-election campaign was funded by public financing, not Blankenship — and elect Justice Beth Walker.

As this corporate money poured into its elections, the West Virginia Supreme Court also found itself in the crosshairs of another corporate-funded group dedicated to making it harder for injured people to file lawsuits.

For years, West Virginia or parts of it made the American Tort Reform Association's (ATRA) annual list of "Judicial Hellholes," supposedly places where "judges systematically apply laws and court procedures in an unfair and unbalanced manner, generally against defendants in civil lawsuits." The group gets funding from the Koch brothers, organizes "astroturf" groups that work to create the impression of grassroots support for tort reform, and has been a major funder of the RSLC. The ATRA recently singled out Davis for what it suggested were conflicts of interest.

The so-called "tort reform" laws promoted by ATRA have a disproportionate impact on the most severely injured plaintiffs. Such laws can be particularly harmful in a state like West Virginia. "With regulatory oversight of mining and other industries so weakened, the right to bring reckless corporations to court is more precious than ever," as the Center for Justice & Democracy has pointed out.

Even though ATRA's list of "hellholes" is based on an unscientific survey of corporate lawyers, Republican legislators used it to justify new tort reform laws that limit lawsuits by injured people. In its most recent report, ATRA praised West Virginia's tort reform laws but said the state's high court "remains a concern and requires a watchful eye."

If any justices are impeached next week and the governor appoints their replacements, the result would likely be a court that the ATRA and the RSLC would prefer: one that puts the interests of corporations over those of ordinary West Virginians.

Tags

Billy Corriher

Billy is a contributing writer with Facing South who specializes in judicial selection, voting rights, and the courts in North Carolina.