Election problems show why Congress needs to restore the Voting Rights Act

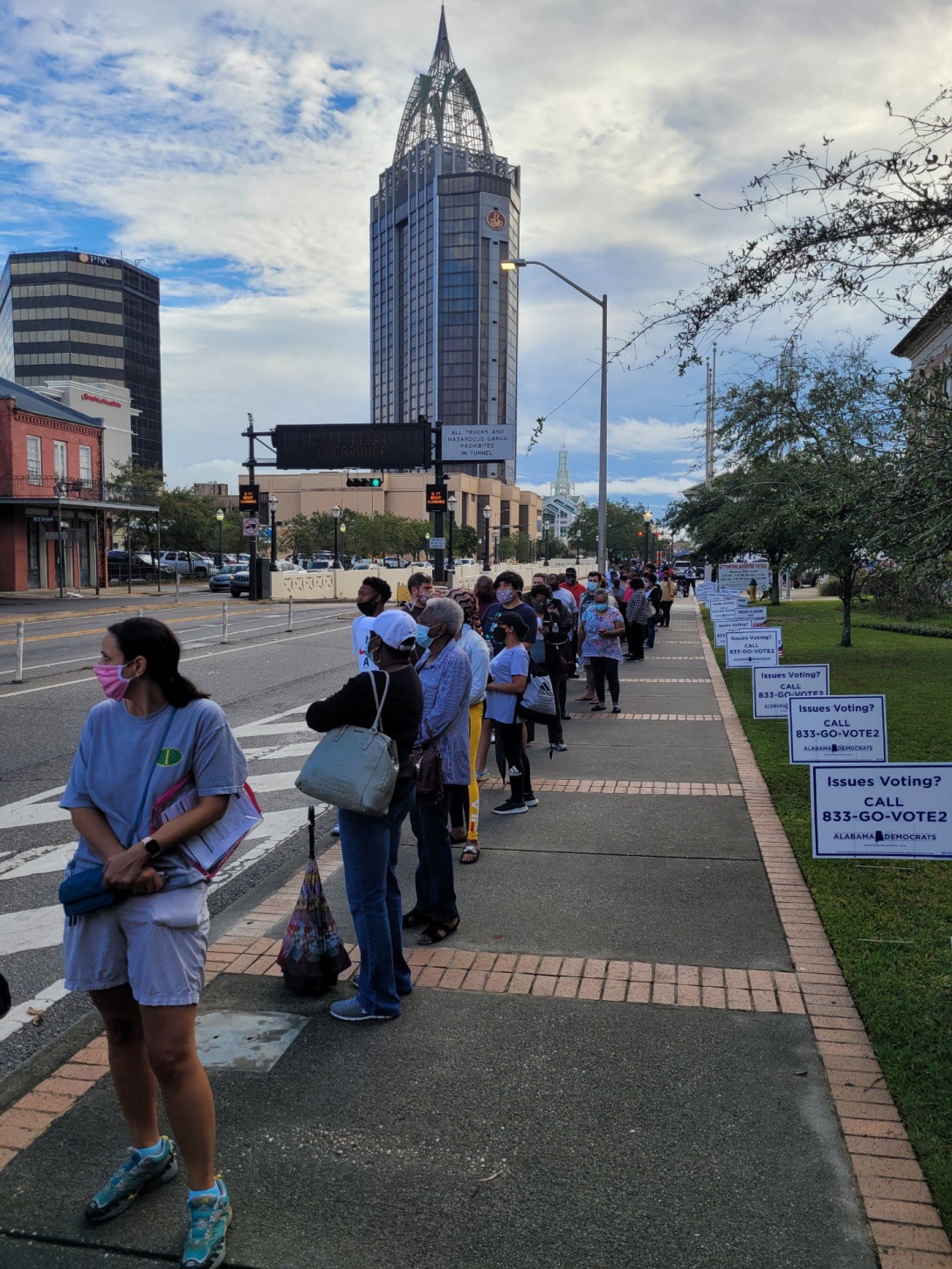

Voters waited in line outside in Mobile, Alabama, to turn in their absentee ballots last month. Alabama is among the states that lack early voting options and where discriminatory election policies burdened Black voters in this election cycle. (Photo via Cliff Albright, cofounder of Black Voters Matter.)

In his Nov. 7 victory speech delivered in Wilmington, Delaware, President-elect Joe Biden thanked Black voters for their support during his campaign. "The African American community stood up again for me," he said. "You've always had my back, and I will have yours." Biden and running mate Kamala Harris — the first Black woman on a major party's presidential ticket — won about 87 percent of the Black vote nationally and more than 90 percent of Black women voters, showing that African Americans continue to be the Democratic Party's most loyal voting bloc.

Black voters helped Biden flip crucial swing states including the Republican stronghold of Georgia, where a Democratic presidential candidate hadn't won in 28 years. The Associated Press reported that almost half of Biden's gains in Georgia compared to Democrat Hillary Clinton's performance in 2016 came from the state's four largest counties — Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett, all located in the Atlanta metro area, and all with large Black populations. According to exit polls, nearly 9 in 10 Black voters in Georgia supported Biden over Trump.

Overall voter turnout in Georgia this year increased by nearly 9 percentage points over 2016, from 59.1% to 67.6%, due to years of grassroots organizing and efforts to combat voter suppression by groups including Black Voters Matter led by LaTosha Brown and Cliff Albright, Fair Count led by Rebecca DeHart, Fair Fight led by Stacey Abrams, New Georgia Project led by Nsé Ufot, and ProGeorgia led by Tamieka Atkins. But despite record-breaking turnout, Black voters were still burdened by discriminatory voting practices this election cycle.

The national Election Protection hotline staffed by voting rights attorneys received nearly 32,000 calls on Election Day alone, as Sherrilyn Ifill of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) reported for Slate. Those accounts, along with reports from LDF's Voting Rights Defender and Prepared to Vote project teams, revealed the pervasiveness of the challenges faced largely by Black voters: long lines, closed polling places, voter purges, faulty voting machines, and voter intimidation, with many of the problems amplified by the COVID-19 crisis.

For example, hours-long wait times were reported at early voting sites in key battleground states including Georgia, Texas, and Virginia, with some voters standing in line for more than 10 hours. In Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott reduced the mail-in ballot drop-off sites to one in each county, a policy that had a particularly dramatic effect on Democratic areas like Harris County, which includes Houston.

In Alabama, voters were required to provide a photo ID and have a notarized signature or two witnesses to complete an absentee ballot. And in Georgia, the number of polling places were cut by almost 10% since 2013 though the state's voter rolls have grown by nearly 2 million in that time. A June 2020 report by the Brennan Center for Justice also found that the average number of voters assigned to a polling place has grown in the past five years in Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — states with large Black populations.

Voting rights advocates argue that long lines are discriminatory, suppressive, and a direct result of the Supreme Court's evisceration of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in its 2013 decision in the Shelby County v. Holder case out of Alabama, which effectively ended federal preclearance for election changes in jurisdictions with a history of voter discrimination. This allowed Republican-controlled state legislatures to implement restrictive voter ID laws, shrink early voting periods, and eliminate some voting locations, all of which disproportionately affect Black voters.

"Let this be clear: Long lines at polling places and early voting sites are not an inevitability," Ifill wrote. "They are a result of voter suppression and deliberate neglect of our voting system that disproportionately affects voters of color."

To address the problem, Ifill and other voting rights advocates are calling for the swift passage of federal legislation that would restore the VRA.

Last year, U.S. Rep. Terry Sewell, an Alabama Democrat who represents the civil rights battleground of Selma, introduced the Voting Rights Advancement Act (H.R.4), which would establish a new formula for determining which states need to pre-clear elections changes with federal authorities. The legislation has been introduced in every session of Congress since 2015, when Sewell originally introduced it. Earlier this year lawmakers agreed to rename H.R. 4 after the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, a Georgia Democrat who was among the peaceful voting rights marchers beaten by police on Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday in 1965, an incident that shocked the nation and led Congress to pass the VRA.

The House approved H.R. 4 last December, but companion legislation introduced in the Senate by Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont remains stalled in the Judiciary Committee, which is chaired by Sen. Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican. The measure is co-sponsored by 46 Democratic and independent lawmakers including Harris and a single Republican, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. Democrats have called on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky to bring the measure to a vote, but so far he has refused.

Biden has promised that one of his first acts as president would be to push for the VRA's restoration — a goal that would be easier to reach if the Democrats win the two Jan. 5 Senate Senate runoffs in Georgia and wrest control of the chamber from McConnell. "The battle for the soul for America has many fronts," Biden said in a statement on the 55th anniversary of the VRA's passage. "The right to vote is the most fundamental."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.