Students learning English face extra hurdles in remote classes

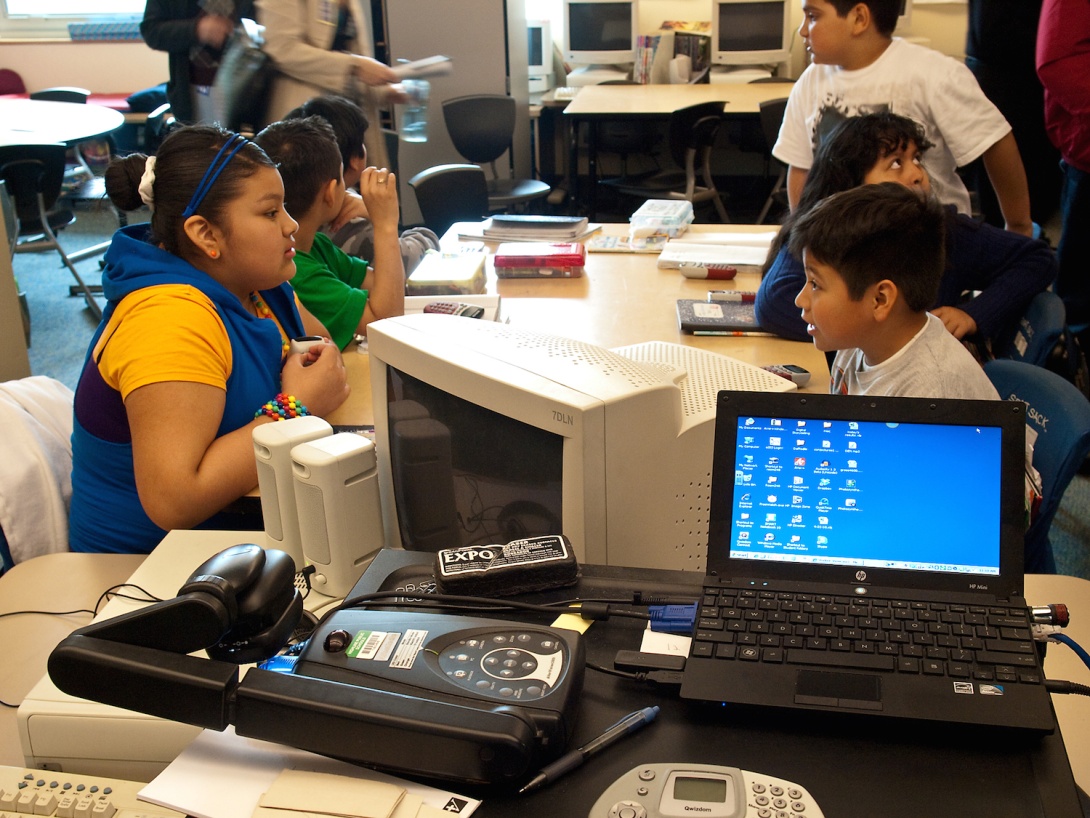

A classroom for English language learners in Washington state, where ELLs comprised nearly 12% of public school student enrollment in fall 2017. Most states with the largest shares of ELL enrollment are in the West, but Southern states like Texas and Florida are also in the group. (Photo by Michael B. via Flickr.)

Zenaida Cruz's 6-year-old child, Kiara, finished kindergarten online last spring and is itching to reenter a classroom for first grade. But citing the pandemic, Kiara's school district — Fulton County, one of Georgia's largest — started the school year remotely.

"She tells me 'Mommy, I miss going to school. I miss being able to run there. I miss my teachers. I don't like staying at home,'" Cruz told Facing South in Spanish.

At home, without a classroom environment or kids her age to interact with, Kiara is falling behind in school. Her progress in English is also stalling, said Cruz. "We're looking for tools so my daughter can learn how to read, because she's not there yet," she added.

Other young English language learners (ELLs) like Kiara will have a tougher time than many of their English-proficient counterparts learning remotely. Many ELLs are also grappling with issues related to poverty and the pandemic that make remote learning even more challenging.

"I think the fear is that even under the best circumstances this form of instruction is simply not ideal" for ELLs says Melissa Lazarín, whose work at the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) deals with issues regarding ELLs. "It is likely that English learners will still not receive the support that they need to meaningfully participate in remote learning and instruction, which could set them back in terms of both their language and academic gains."

More than 6,000 students in Fulton County schools and around 5 million public school students nationwide — more than 10% of total student enrollment — are ELLs. While most states with the largest shares of ELL enrollment are in the West, several Southern states* also have large enrollments: 18% of public school students in Texas were ELLs in fall 2017, 10.1% in Florida, 9.1% in Virginia, 8.3% in Arkansas, 6.9% in North Carolina, 6.6% in Georgia, and 6.1% in South Carolina. In all other Southern states, ELLs accounted for no more than 4.6% of public school enrollment, with West Virginia coming in last nationwide at below 1%, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Most ELLs nationwide are Hispanic, the U.S.-born children of immigrants. The vast majority also live in poverty. According to a 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Education, nearly six out of 10 students enrolled in ELL programs in the 2010-2011 kindergarten class lived in families with incomes below the federal poverty line. That compares to just two out of 10 non-ELL kindergarteners.

In the graphic below, each bubble represents a school district in the South where ELLs comprised at least 5% of student enrollment during the 2018-2019 school year. The larger the share of ELLs in a district, the bigger and more central the bubble. Among these districts there is diversity in ELLs, from first-generation American ELLs in Georgia's Fulton County Schools, to the many formerly unaccompanied child migrants who attend Harrisonburg City Public Schools in Virginia.

Many of these districts have started classes online. In Texas, several school districts that started classes remotely are among those with the South's largest shares of ELL student enrollment. For example, nearly 70% of students in the Roma Independent School District along the Rio Grande in South Texas are ELLs. In Gainesville City schools in Georgia, which also started the school year remotely, nearly 30% of students are ELLs. Last spring, the district also moved classes online.

"The greatest challenge our [ELL] students faced was the limited support in the homes," Gainesville City School System Superintendent Jeremy Williams told Facing South in an email. "The inability to consistently interact and reinforce learning was a struggle."

Williams noted that the families of ELLs in his community are employed primarily by the poultry industry. In Georgia and elsewhere, the immigrant-dependent industry has struggled with COVID-19 outbreaks. Working in facilities that may put them at high risk of infection has been an added stressor for many Gainesville ELLs' families, according to a community organizer Facing South spoke to.

In addition, rural school districts across the South may lack the teacher support to effectively reach immigrant ELL students, adds Lazarín from the MPI. "The challenge is really compounded in these communities," she told Facing South.

Poor internet connectivity in the South's rural areas is yet another challenge. "It's a matter of location," said John McCann, spokesperson for the public school district in rural Chatham County, North Carolina, where ELLs comprise more than 10% of district enrollment. "Even in doing our best to provide things like hotspots to help families get online, those hotspots don't do [any] good if there's no cellphone coverage."

When Chatham County schools went online last spring, school staff went the extra mile to provide schoolwork for students with internet problems, said McCann. "We had educators who were visiting those families' houses and delivering hard copies of the materials, again, just trying to fill in those gaps."

Online, he said, several ELLs struggled with what are known as "oracy skills" — finding the right words to express themselves. Dealing with that remotely can be difficult for teachers. "If you and I are face to face, I can use body language or mimic certain things with my body to get my point across … to help you build that vocabulary," McCann said. That's more challenging to do online.

* Facing South defines the region as including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Tags

Rolando Zenteno

Rolando Zenteno is the inaugural recipient of the Julian Bond Fellowship with Facing South.