Southern primaries offer critical lessons for November

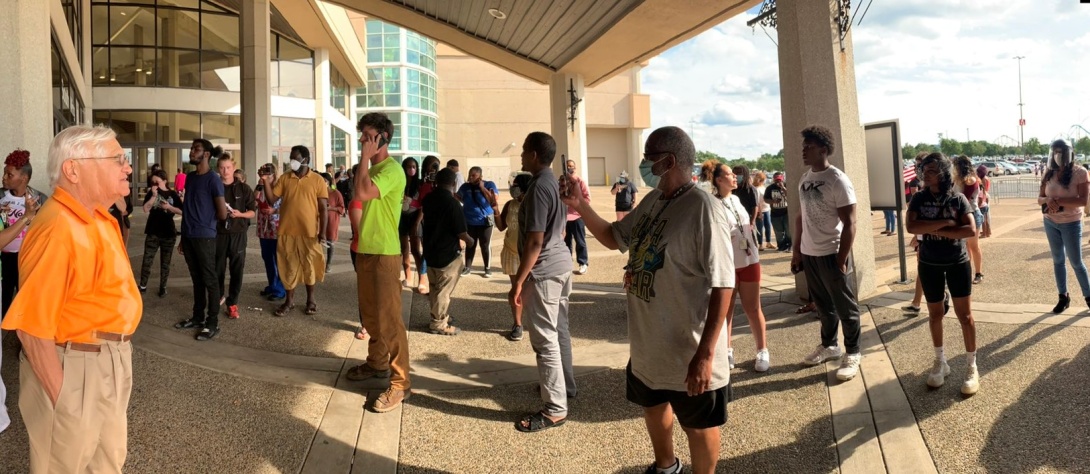

During the recent Kentucky primary, the decision to have one centralized voting location in Jefferson County at the Kentucky Expo Center in Louisville led to a late-day traffic jam and voters being locked out of the building after the polls closed at 6 p.m. A judge eventually extended voting for half an hour. (Image via Black Voters Matter Twitter page.)

After participating in Georgia's June 9 primary election, LaTosha Brown, a co-founder of Black Voters Matter, documented her disturbing experience on Twitter. It took Brown three hours to cast a ballot at her polling site in Union City, a suburb south of Atlanta that is 88 percent Black. Her experience was part of a broader pattern of election day problems in Georgia, which also included voters not getting requested absentee ballots. Brown and other voting rights advocates see the state's election failures as part of a longstanding pattern of mismanagement and voter suppression that disproportionately impacts Black communities.

"As a Black person I was actually sad. I was thinking to myself, 'How long do we have to be going through this?'" said Brown. "This is supposed to be a new system but we continue to see old problems."

A main cause of Georgia's primary election debacle was the state's new electronic voting system, with 30,000 voting machines being used for the first time. Georgia decided to institute the new system after widespread allegations of voter suppression during the state's 2018 gubernatorial election. Voting rights experts characterized that election as "a systemic breakdown of its electoral process," which many experts say resulted in Democrat Stacey Abrams' narrow loss to Republican Brian Kemp for the governorship in a race that was overseen by Kemp, who then served as secretary of state. In the run-up to this year's primary, security experts warned that the state's new voting system would not be ready, especially amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Despite the warnings, state officials proceeded without adequate planning or election infrastructure, which led to what state Sen. Nikema Williams, chair of the Georgia Democratic Party, called a "hot mess." Many of the machines were reported to be missing or malfunctioning on the day of the primary, which overwhelmed local election officials. Voters experienced long lines and wait times at some polling locations — especially in precincts with large concentrations of Black voters.

There were also fewer polling places and poll workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and poll workers brought in at the last minute to help out were sometimes poorly trained, adding to the confusion. In addition, many voters who requested absentee ballots never received them and had to choose between protecting their health and going to vote in person. Furthermore, Georgia officials decided against providing prepaid postage on mail-in ballots, which voting rights advocates said essentially amounted to a poll tax.

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) blamed local officials in Atlanta's largely Black counties of Fulton and DeKalb for primary day problems, accusing them of being unprepared to implement the state's new voting system. While local officials have acknowledged that the counties became overwhelmed with requests for absentee ballots and lack of polling place workers, many are demanding that Raffensperger acknowledge some culpability. "He's the head election official in the state, and he can't wash his hands of all responsibility," said Fulton County Election Director Rick Barron.

Voting rights advocates have long warned that failing to provide adequate resources to elections would ultimately lead to a surge in disenfranchisement, a concern only intensified by a national health emergency. Back in April, Congress passed a stimulus package that provided $400 million for funding election protections in the states, but voting rights advocates said at the time that was not enough.

"The ACLU warned that insufficient resources were allocated for polling places, machines, in-person election staff, and staff to process absentee ballots and that this would result in the disenfranchisement of voters in 2020," Andrea Young, executive director of the ACLU of Georgia, said in a statement released on primary election day. "It gives us no pleasure to be proven right."

And with Georgia emerging as a presidential battleground state that could also determine control of the U.S. Senate, making elections safe and secure ahead of November is more important than ever.

Bipartisanship in Kentucky

Despite some dire predictions, the election problems that plagued Georgia were not replicated in Kentucky's June 23 primary. Voting rights advocates say the state avoided mass election failures because of bipartisan support for election safeguards, including extended early voting and the expansion of mail-in voting. In April, Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear reached a bipartisan agreement with Republican Secretary of State Michael Adams to expand voting by mail. Adams was against mail-in voting when he ran for his position in 2019, but the pandemic changed his mind.

In a historic primary turnout, an estimated 1.1 million Kentuckians voted — and 75% did so by mail in a state where typically only 2% of voters cast absentee ballots. "Investment in election infrastructure, coordination between state and local authorities and bipartisan cooperation can make a real difference in ensuring that people can vote safely," said Larry Norden, director of the Election Reform Program for the Brennan Center for Justice. Kentucky's primary election received national attention because of the competitive Democratic contest to decide who will face U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell in November. This week, the race was called for retired Marine fighter pilot Amy McGrath, who narrowly beat state Rep. Charles Booker.

But the election wasn't without flaws and revealed some of the problems states will have to address by November. For one thing, shifting election resources to encourage voting by mail led to a reduction of Kentucky's in-person voting sites from 3,700 to just 170, leading to accessibility concerns. "People often think that voter suppression is this big, bad entity, and it can be," said Beth Thorpe, a Democratic strategist and communications chair for the Louisville Democratic Party. "But it can be much more subtle in the way we create systems and how we think about access, including things you can't know in advance."

Most Kentucky counties decided to only have one polling place, which voting rights advocates said disadvantaged residents who live further away, lacked transportation, and/or have disabilities. Experts also say that the reduced number of polling places caused logistical problems including parking jams and limited access for voters with disabilities, which in some places led to long lines and extended wait times.

For example, Jefferson County, which includes Louisville, the state's largest city, opted to consolidate all of its in-person voting at the sprawling Kentucky Expo Center. As required under state law, election officials closed the doors at 6 p.m. But voters who had waited until late in the day to cast ballots found themselves stuck in a traffic jam in the parking lot and then encountered a locked building. They pounded on the glass doors and shouted, "Let us in!" The outcry from frustrated voters and politicians ultimately led a judge to grant an injunction keep the polls open until 6:30 p.m.

Voting rights advocates worry there could be similar problems in November for states depending heavily on mail-in-voting. They are calling on lawmakers to guarantee viable in-person voting options in order to ensure that individuals from marginalized communities are not locked out of the process.

"Offering just one site on election day presumes we have reached everyone, and we don't have to work as hard on election day, and that thinking is dangerous," said Kristen Clarke, executive director for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. "In the primaries, we're just getting a taste of what turnout will look like in November."

Tags

Benjamin Barber

Benjamin Barber is the democracy program coordinator at the Institute for Southern Studies.