Populists and Bourbons are fighting again, 21st century style, in Mississippi

By Joe Atkins, Labor South

OXFORD, Miss. -- More than a century ago the "forgotten man" of Mississippi and across the South -- the farmer, the common worker -- decided he'd had enough of "Wall Street speculators who gambled on his crop futures; the railroad owners who evaded his taxes, bought legislatures, and over-charged him with discriminate rates; the manufacturers, who taxed him with a high tariff; the trusts that fleeced him with high prices; the middleman, who stole his profit."

The forgotten man was so angry, historian C. Vann Woodward goes on to say, that he created a movement. It came as close to toppling our two-party system as any effort in the country's history.

The parallels between the Populist movement of the 1890s and early 1900s and today's Tea Party are striking, even though crucial differences also exist.

State Senator Chris McDaniel's still-contested narrow loss to incumbent U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran in Mississippi's Republican runoff last month exposed a divide with the Republican Party possibly as wide as the divide that ultimately split the one-party Democratic South in the 1890s between the "Bourbon" establishment and the rebellious "Populists."

Voting in the June 24 runoff even paralleled the Bourbon-Populist split at the turn of the last century. McDaniel won the old Populist stronghold in the Piney Woods region of southeast Mississippi while Cochran secured the Bourbon stronghold of white voters in the Delta.

The ruling Bourbon Democrats who emerged after the Civil War were pro-big business and made sure government stayed friendly to the railroads and other Northern corporations. They fought any regulation or taxes on big business but ignored the needs of the little guy whose hard work made business leaders rich.

The very embodiment of Bourbon politics today is Haley Barbour, the prominent Washington, D.C. lobbyist and former Republican Mississippi governor who helped lead the charge for fellow Bourbon -- "Country Club" is the preferred term today -- Republican Thad Cochran's re-election. Barbour's nephews Henry and Austin worked in Cochran's campaign, and an FBI investigator isn't needed to see Haley's fingerprints on millions that flowed into friend Thad's campaign.

After all, Barbour's oft-ballyhooed influence in Washington owes much to Cochran, a former chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee. A prime example: the $570 million in federal housing assistance for Hurricane Katrina victims that Cochran helped divert into Barbour's "Port of the Future" project in Gulfport, Miss., which is thus far a boondoggle that has failed to deliver the promised jobs.

McDaniel and the Tea Party despise Barbour and his Country Club friends, who they feel are part of the Big Government-Big Business alliance that is responsible for the corporate bailouts of the 2008 recession, the $17 trillion-dollar federal debt, and soft-peddling of the immigration issue. They believe both parties ignore the daily struggles of average Americans.

Tea Partyers' hands aren't exactly clean of corporate stain. Billionaire oilmen Charles and David Koch are big backers. So is the anti-union Club for Growth organization, which spent millions on McDaniel's campaign.

Still, they have a point regarding politics in Washington.

The mainstream Republican Party is essentially a tool of Wall Street and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. What the split Congress can't deliver, the U.S. Supreme Court's pro-corporate majority provides.

Tea Partyers see Democrats as practically socialists, but the sad truth is that many national Democrats are as cozy with Wall Street as Republicans. Former President Clinton gave us NAFTA and helped repeal the Glass-Steagall Act that regulated financial services. The presence of Timothy Geithner, Larry Summers and Robert Rubin in Obama's first-term inner circle proved Wall Street still had a friend in the White House.

Big Corporations "want to be able to play both sides of the aisle," writes historian Kim Phillips-Fein in the current edition of New Labor Forum, "and they want to be close to power regardless of which party holds Congress and the White House."

The dilemma in American politics is that Wall Street is amoral, self-interested, and in today's global economy incapable of allegiance to any nation. "Deep down, all of them know that they do not really care -- that their own enrichment matters much more than any collective purpose or common vision," Phillips-Fein writes.

Tea Partyers know this, but much of their anger is misdirected. Unlike the Populists of the 1890s, they despise organized labor. Their benefactors -- the Koch brothers and the Club for Growth -- would have it no other way. The old Populists wanted government to serve the people. The Tea Partyers want government to go away.

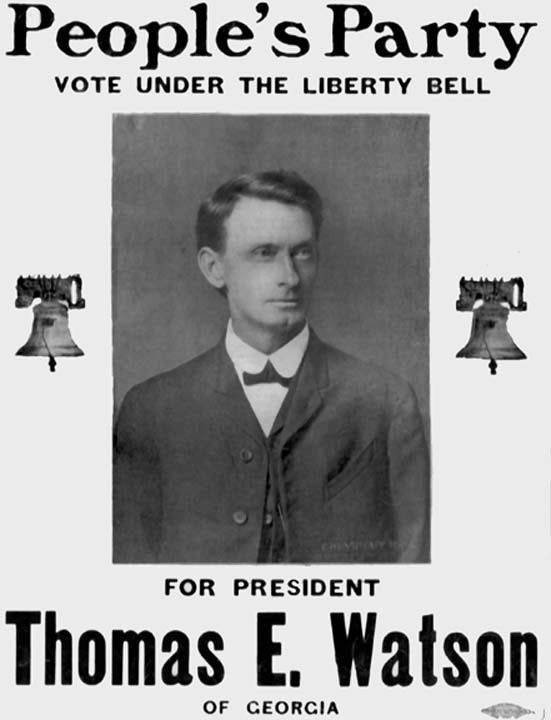

Led by Georgia politician Tom Watson, the old Populists initially welcomed blacks into their ranks -- a rare enlightened moment in the South's tortured history -- but then became bitterly racist when black support turned to the mainstream parties. Jim Crow ultimately made black support irrelevant in the South.

Today's Tea Partyers are overwhelmingly white, and their downfall may be their inability to accept the nation's changing demographics. Their obsession with immigration and migrant workers, for example, betrays their failure to see a bigger picture, that brown-skinned and black-skinned folks are not the problem. Tea Partyers are too blind to see it.

Tags

Joe Atkins

Joe Atkins is a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi and author of "Covering for the Bosses: Labor and the Southern Press." A veteran journalist, Atkins previously worked as the congressional correspondent with Gannett New Service's Washington bureau and with newspapers in North Carolina and Mississippi.