How slavery continues to shape Southern politics

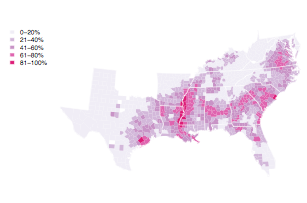

Whites who live in areas of the South once dominated by the plantation economy and slavery are much more likely than other Southerners to express colder feelings toward African Americans, to oppose affirmative action, and to vote Republican.

Those are among the findings of a groundbreaking new study titled "The Political Legacy of American Slavery" by a team of political scientists from the University of Rochester in New York. It was based on a county-by-county analysis of census data and opinion polls of more than 39,000 Southern whites.

"Slavery does not explain all forms of current day racism," says Avidit Acharya, who conducted the study along with Matthew Blackwell and Maya Sen. "But the data clearly demonstrates that the legacy of the plantation economy and its reliance on the forced labor of African Americans continues to exacerbate racial bias in the Deep South."

To explain their results, the authors theorize that Southern whites -- faced with having their political and economic power undermined by emancipation -- had incentive to propagate racist violence, institutions and norms in parts of the region like the so-called "Black Belt" or "Cotton Belt" that had high numbers of freed slaves in the decades after 1865.

"We argue that these attitudes have, to some degree, been passed down locally from one generation to the next," they write.

The researchers looked at data from 93 percent of the 1,344 Southern counties in the Black Belt where plantations dominated the economy from the late 1700s into the early 1900s. They found that a 20 percent increase in the percentage of slaves in a county's pre-Civil War population is associated today with a 3 percent decrease in whites who identify as Democrats and a 2.4 percent decrease in the number of whites who support affirmative action.

What they call the "slavery effect" accounts for up to a 15 percentage point difference in party affiliation today. About 30 percent of whites in former slave plantation areas report being Democrats, compared to 40 to 45 percent of whites in counties where slaves made up less than 3 percent of the population.

The researchers considered whether there could be alternative explanations for their findings. For example, they looked at whether whites who live around larger black populations have more negative racial attitudes -- what's known as the "theory of racial threat." But they found that share of black population actually predicts warmer attitudes toward blacks among whites once slavery is accounted for.

They also considered whether what they found was related to slavery being more prevalent in rural areas, which tend to be more conservative than urban areas, or whether it had something to do with Civil War destruction, or with whites holding particular racial attitudes migrating to areas with others of like mind. But again, those hypotheses did not hold up to scrutiny.

The study also compared Southern counties with very few slaves in 1860 to non-Southern counties with no slaves in the same period. It found very little difference.

"Thus, in the absence of localized slavery, it appears that the South would have had a distribution of present-day political beliefs indistinguishable from comparable parts of the North," the authors write. "This provides evidence that the effect that we see comes primarily from the local presence of many slaves, rather than state laws permitting the ownership of slaves."

The researchers point to an emerging literature showing that the legacy of slavery can be observed today in other contexts internationally -- from lower levels of household consumption and childhood growth in areas of Peru and Bolivia where people were subject to forced labor, to higher poverty, reduced school enrollment and lower vaccination rates in parts of Colombia where gold was mined by slaves.

The authors will present their findings at the Politics of Race, Immigration, and Ethnicity Consortium at the University of California at Riverside on Sept. 27.

"In political circles, the South's political conservatism is often credited to 'Southern exceptionalism,'" says Blackwell. "But the data shows that such modern-day political differences primarily rise from the historical presence of many slaves."

Tags

Sue Sturgis

Sue is the former editorial director of Facing South and the Institute for Southern Studies.