The South and "the Great Gerrymander of 2012"

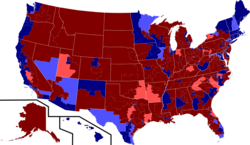

In a recent New York Times analysis, Sam Wang looked at an issue which has been grabbing headlines -- at least on political blogs -- since the 2012 elections: how Democrats, despite winning 1.4 million more votes than their GOP counterparts in U.S. House races, found themselves at a 234 to 201 disadvantage in Congress' lower chamber after Election Day.

We wrote about this at Facing South in January, noting that the mismatch between Democratic votes and Democratic representation was roughly four times greater in Southern states than in the rest of the country.

In Wang's analysis, North Carolina is singled out as an especially egregious example of the voter-to-representative disconnect. Despite Democrats garnering 51 percent of the overall U.S. House vote in the state, Democrats ended up with only four out of 13 of the seats -- something Wang said happened in only 1 percent of his random simulations, meaning it was no accident.

Florida, Texas and Virginia are also mentioned as examples of the impact districts can have on skewing the alignment between votes and politicians.

The most common explanation -- and the one singled out by Wang and myself in Facing South -- is partisan gerrymandering. That certainly was the goal of groups like the Republican State Leadership Committee, which -- as Facing South was one of the first to document in 2010 -- openly advocated the (far-from-novel) strategy of capturing state legislatures in time to control the redistricting process.

But as the debate over gerrymanding has intensified since the 2012 elections, political observers have pointed out that it may not be so simple.

For one, not all of the states with the greatest mismatches between votes and representation have been the victims of hyper-partisan gerrymandering. While the GOP-created lines clearly influenced the North Carolina outcome, for example, Republicans can't be blamed in Arkansas, where despite nearly 30 percent of voters choosing a Democrat in 2012, zero U.S. House members are Democrats.

Why? As one Facing South reader pointed out, Democrats still controlled the legislature when the maps were made after 2010. However, their majorities had greatly diminished: Going into the 2010 elections, Democrats had a combined 98-36 edge in the state senate and house; after 2010, the margin narrowed to 75-60, and Democrats were apparently unable or unwilling, to the chagrin of Democratic observers, to use this thinner majority to push through Democratic-friendly maps. (Republicans captured both chambers in the money-drenched 2012 elections.)

Another explanation is geography. As several analysts have pointed out, Democratic voters have become more concentrated in urban areas -- something definitely true of "New Majority" voters in the South. As a result, the argument goes, Democrats get naturally packed into certain districts, where they have run up big vote totals out of line with Republicans, who are more spread out.

But while it may be true that Democrats are increasingly urban, it doesn't necessarily follow that election results have to be so lopsided as a result. Looking at such classically engineered Congressional districts as North Carolina's 12th, it's clear that political mapmakers in the past have been more than willing to carve out areas that mix pieces of metro centers with rural areas.

The question is whether new, nonpartisan districts could continue to include such a mix to increase competitiveness while still hewing to criteria like those outlined by Arizona's independent redistricting commission, such as compactness, "incorporation of visible geographic features," and -- crucially in the South -- compliance with the Voting Rights Act.

A widely circulated analysis by Nicholas Goedert looking at the impact of geography concluded that "states that are heavily urbanized ... are more distorted against Democrats than more rural states" -- but it also found that gerrymandering remained a crucial factor: "Republicans gained benefits across the board from controlling the redistricting process."

The range of forces at work mean that no one solution will likely solve the problem. Florida's Fair Districts initiative clearly helped level the playing field for Democrats and lessen the representation mismatch in 2012. But as groups like FairVote point out, the reality of winner-take-all elections is that there will often be big losers; they advocate alternatives like choice voting as a more long-term structural fix.

Either way, it's clear that interest in reform is growing. Given that many, if not most, in Congress have a natural investment in the status quo, it will take an upswell of public pressure to bring change. As Wang closed his analysis for the Times:

It’s up to us to take control of the process, slay the gerrymander, and put the people back in charge of what is, after all, our House.

Tags

Chris Kromm

Chris Kromm is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies and publisher of the Institute's online magazine, Facing South.