Super Tuesday, the Tea Party and the South: Preaching the gospel of raw capitalism and the evils of government

By Joe Atkins, Labor South

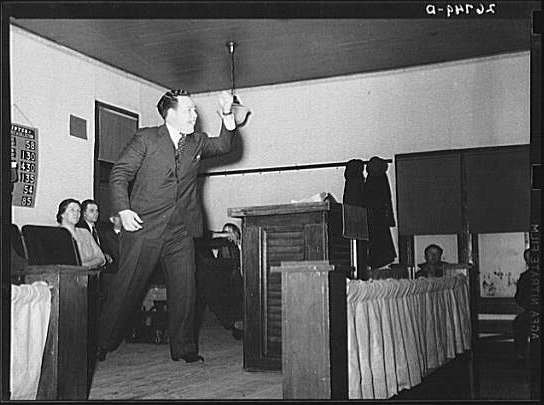

I'm a Catholic who grew up in the Pentecostal Holiness Church, and I'll never forget the little Macedonian Pentecostal Church outside of Sanford, N.C., where my Uncle Eb preached. From the pulpit he reminded me of an Old Testament prophet with his eagle eyes, beak nose, and gravelly voice.

When my father, my brother and I were the only three in the congregation not to answer the call to come forward and pray at the altar one Sunday, Uncle Eb stared at us across the church and warned, "Remember, you're not too young to go to hell."

I loved those people even though Uncle Eb inspired some pretty scary visions of hellfire and damnation. They were hard-working farmers and textile workers, far from wealthy, many poor, some dirt poor, and their faith was the rock-ribbed center of their lives. They spoke in tongues, danced up and down the aisle, waved their hands in the air to feel the Holy Ghost about them. The preacher never talked about the wonders of wealth and capitalism although he gave Elvis Presley and his ilk a hard time occasionally.

It was certainly not the Pentecostal Church you've seen and come to know on television since the days of Jim and Tammy Bakker, a church that seems to revel in its wealth, that surrounds itself with the trappings of material goods, and whose leaders often equate a no-holds-barred capitalism with Christianity itself.

That's the Pentecostal Church, along with other Protestant denominations and many Catholics, that has allied itself with the Tea Party movement and a hard-right Republican Party that wants to install corporate rule in this country. That's why you’re hearing GOP presidential contender Rick Santorum (a Catholic) talking about breaking down the wall between church and state, resurrecting abortion, homosexuality, and even birth control as issues that should concern Americans even more than jobs.

As the March 6 "Super Tuesday" primaries approach and voters go to the polls in Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, Oklahoma, and other states, bear in mind that Southerners dominate the Tea Party that is so central to Republican politics today. Purdue University history professor Darren Dochuk, in the New Labor Forum (Winter 2012 edition), says 39 of the 62 members in the congressional Tea Party Caucus are from the South, including 12 from Texas. Actually, he writes, they are part of a long-standing tradition of conservative evangelical leaders who've been aligning themselves against liberal Democrats since at least the New Deal.

In the 1940s, CIO organizer Lucy Randolph Mason, a Virginia aristocrat and committed Episcopalian who believed in the labor cause, often found herself face to face with the mill village minister, a man usually totally compromised by the financial support he got from the mill owner and one who thus considered labor unions minions from hell. She describes one of them, Preacher Jones, in her autobiography To Win These Rights: "The preacher dropped his bull-like head and hunching forward said to me: 'You don't believe in no kind of religion -- you believe in a social religion and that ain't Christianity … .' I, too, leaned forward and asked earnestly, but politely: 'Then you don't believe in the teachings of Jesus? … His whole life … (was) all part of a great social religion.'"

In the modern South, Pentecostal, Methodist, and Baptist leaders are joined by first generation Southerners who came to Atlanta, Nashville, and the Research Triangle in North Carolina with their business and engineering degrees and pro-business ideas, set up shop, and laid the foundation for the rise of Sunbelt South politicians like Newt Gingrich and George W. Bush. For those politicians, the old bugaboo of communism that preachers used to fire congregations back in the 1940s was replaced by the bugaboo of government.

But, just as Preacher Jones was a tool of the mill owners to keep the workers pliant and passive, the religious right today is also merely a tool for the oil barons and Wall Street types who truly rule. In the 1950s and 1960s, Dochuk writes, oilmen H.L. Hunt and J. Howard Pew stayed busy "marshaling their fellow church folk in fights for right-to-work legislation and the deregulation of industry."

From time immemorial, "the Southern oil business has been dominated by petro-patriarchs who have used their company profits to fund evangelical institutions that legitimate their business pursuits. The marriage has always been a natural one: in the freewheeling culture of Southwestern oil -- where high-risk, high-reward wildcatting has romanticized the rags-to-riches man who demands to be left alone -- evangelicalism has celebrated its own fierce, masculine individualism."

Instead of Hunt and Pew, today we have the Koch brothers.

Make no mistake: MONEY is their one ultimate principle, their god, not religion, not the teachings of Jesus Christ. In the past they used fear of communism, socialism and civil rights on the bully pulpit to stir up the great unwashed. Today it's government.

That's why there's something sickening when a right-wing Republican like U.S. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor gets a ton of positive publicity, as he recently did, for paying lip service to the civil rights movement. Last week Cantor, joining with civil rights legend and Democratic House member John Lewis of Georgia, pushed through the Republican-dominated House a resolution to preserve the stories of members of Congress who participated in the movement.

Ah, the civil rights movement, so safely tucked away in the history books now. Let's praise it and show how progressive we can be 40 years after the fact. And after we do, let's get back to the business of the day and make sure those civil rights don't interfere with the markets or with our corporate friends, the people we truly serve.

Tags

Joe Atkins

Joe Atkins is a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi and author of "Covering for the Bosses: Labor and the Southern Press." A veteran journalist, Atkins previously worked as the congressional correspondent with Gannett New Service's Washington bureau and with newspapers in North Carolina and Mississippi.