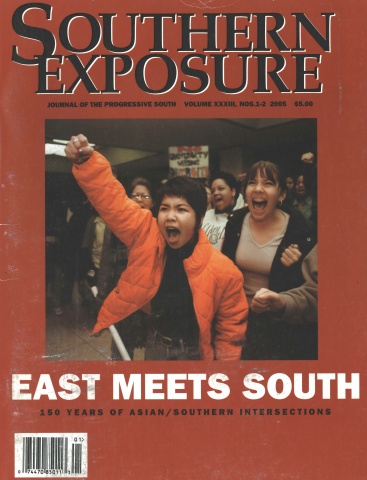

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

Two tales of East Meets South:

Circa 1990: A young Chinese-American woman, born and raised in Massachusetts, moves to the Triangle area of North Carolina for graduate school. She isn’t too surprised by the “where are you from” questions that she often gets around town. They’re irritating and exhausting, especially when people refuse to accept “Massachusetts” or “America” as an answer and persist in wanting to know where she’s “really from.” But she’s caught off guard when, one time, a white person asks, “Are you from Fayetteville?” Why Fayetteville? Is there a big population of Asians in Southeastern North Carolina that she hasn’t heard about? It doesn’t make sense. Eventually she figures it out. Fayetteville is home to Fort Bragg: people are asking if she’s from there because they think she might be married to an American soldier from the base. In their eyes, an Asian woman in the South can only be a “war bride.”

Circa 1989: A teenage immigrant moves with her family from Hong Kong to California. Among the various keepsakes she brings with her across the Pacific is a hymn book from the school she had gone to all her life. She isn’t Christian, but her school had been: it was founded by Baptist missionaries in the 19th century. Many childhood memories are wrapped up in the songs from that hymn book, like the cheery jingle that the teachers always made the kids sing on Field Day, with lyrics (in Chinese, of course) that spoke brightly of the healthy benefits of sports. Fast forward a couple of years: our teenager, now an American high schooler, catches a few bars of that old Field Day song on TV. The show is, of all things, a Civil War documentary. That little jingle she liked so much back in Hong Kong, she learns, has different, English words, and an American name: “Dixie.”

In 1984, Southern Exposure published a special issue on the history of the Chinese in the South. Focusing on Chinese-American communities in Louisiana and Mississippi, articles in the issue chronicled the post-Civil War migration of so-called “coolie” laborers to the Deep South—brought there initially as replacement for newly emancipated African Americans—and explored the complex three-part racial system that developed in places where these migrants settled. The editor’s introduction to the issue explained why it’s important to remember this history: “While it is clear that the racist practices spawned during the plantation era are still active in the continued political and economic subordination of African Americans, their impact on other people of color in the South is less visible. Yet a true picture of race relations, and more importantly, a blueprint for progressive change cannot be developed without expanding our understanding of the roots of racial oppression and the impact of racism on all people.” Twenty-one years later, these words still ring true—all the more so because the racial landscape of the South has been reshaped so dramatically in the last two decades. The increase in Latino immigration has received a good deal of attention, both here in the pages of SE and in the media at large. In this special issue, then, we turn to a less talked-about aspect of the “New New South”: the growth of Asian American communities and its implications for Southern culture and politics.

In 1965, the federal government lifted long-standing prohibitions against Asian immigration and naturalization that dated back to the Chinese Exclusion laws of the late 19th century. Since then, the population of Asians/Pacific Islanders (APIs) has increased rapidly nationwide—and nowhere as rapidly as in the South. While the West Coast remains the population center for Asians in the U.S., the South has now edged out the Northeast as the region with the second highest number of Asian residents. According to a 2002 U.S. Census Bureau report, our region is home to an estimated 2.36 million APIs (roughly one-fifth of all Asians in the U.S.), with the greatest concentrations in Houston and the greater Washington, D.C., area.

The legacies of 20th-century wars and the vicissitudes of 21st-century global economics have led to the creation of Asian-American communities markedly different from the South’s late 19th-century Chinese settlements. The Asian-American population of the South today traces its roots not only to China, but also to Bangladesh, Cambodia, Japan, Korea, India, the Philippines, Viet Nam, to name only a few points of origin. Socio-economically, Asian Americans in the South run the gamut from children of middle-class immigrants with bankable advanced degrees to newly-arrived refugees struggling to restart their lives from scratch. They come for reasons that are “obvious” (e.g. economic opportunities) as well as ones that don’t fit traditional models of immigration. The very characteristics that make some people think of the South as an unlikely destination for Asian immigrants—the influence of military culture, the dominance of Protestant Christianity—are sometimes responsible for bringing or attracting Asians to the region. Such is the case with foreign spouses (especially wives) of U.S. servicepeople, or refugee families sponsored by local church groups for resettlement.

The articles in this issue give us insight into a wide range of Asian-American communities in the South, many right here in North Carolina. One important theme that emerges from these stories is that many Asians are in America today because of the long-standing and ongoing military, economic, and cultural presence of Americans in Asia. To understand how East has met South, then, we have to look not only at demographic shifts within the American South, but also at Southern “footprints” in Asia. We have to confront both the new realities and forgotten histories of the South.

Despite this steady growth of Asian populations in our region, they have remained largely invisible in discourses of Southern history, society, and politics. As the civil rights attorney Milan Pham observes in her interview with us, getting governmental institutions, the media, and the citizenry at large to recognize Asian Americans as a marginalized minority can be a big challenge. The persistence of the black-white binary, combined with widespread stereotypes of Asian success, mean that Asians are often left out of discussions of social injustice. Asian-American activists who raise demands of structural change are often met with the bewildered reply, “But you’re not supposed to have any problems. . .”

Kiran, a South Asian anti-domestic violence advocacy group based in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area, is part of a new crop of Asian-American community organizations that have emerged across the South to fill the gaps in existing social services. These gaps, as Kiran co-founder Shivali Shah suggests, reflect a general lack of understanding about the social and economic ramifications of being an immigrant. Many women that Shah works with come to the U.S. on spousal visas that forbid them to work or even in some cases open their own bank accounts. It’s easy to see how such restrictions can affect the financial and emotional power balance within a marriage, especially in situations of abuse. Too often, however, social service providers who attempt to work with South Asian domestic violence victims are fixated on simplistic notions of cultural and religious differences (for example, the idea that Muslim families are hopelessly patriarchal) that prevent them from seeing the complex social worlds that their clients actually inhabit.

The narrative of Asian success thus masks important stratifications within the Asian-American population—stratifications that have to do with gender (as Shah shows) as well as class, ethnic/national origin, and English-speaking ability. It’s also worth noting that the “model minority” stereotype is a relatively new media invention that gained currency during the Civil Rights era, as part of an ideological backlash against black protest and resistance. The script goes: “If the Chinese and the Japanese can succeed on the basis of hard work alone, why can’t blacks and Mexicans?” It is a classic divide-and-conquer strategy that draws attention away from key moments in history when Asian peoples have been subjected to forms of oppression we typically associate only with African Americans—and when Asians and blacks have come together in trans-racial solidarity. Sam Lowe’s piece, “They Were Fighters,” shows how white planters in the Deep South, like their counterparts in Cuba and other Caribbean islands, regarded the Chinese as a heathen race and exploited them as a substitute workforce for recently-freed slaves. By calling attention to the neglected history of the Chinese coolie trade, particularly the story of Chinese participation in anti-colonial struggles in Cuba, Lowe shows that Asians and blacks have played similar roles in the great pan-American drama of race, labor, and resistance.

This is not to say that Asians and blacks always experience racism in the same way, now or in the past. In fact, as the articles in the 1984 SE issues show, within a couple generations of settling in the Delta, the Chinese were able to carve out a niche as economic and social “middlemen” between whites and blacks, even gaining access to some white-only institutions. Johanna Miller Lewis’s article, “Looking like the Enemy,” provides a more complex example of this racial triangle. While the internment of Japanese Americans in World War II—and the racist impulse that ignited its proliferation—is often associated with the American West, Lewis reveals that southern Arkansas was also keeper of two internment camps. Examining the little-known history of the Rohwer and Jerome camps in Jim Crow Arkansas, Lewis explores the ambiguous racial position of the Japanese internees. Because they were not black, white camp administrators and other local whites exempted them from certain rules of segregation. Yet their non-blackness had little meaning when it came to the Federal government’s decision to uproot and imprison them in the name of “national security.”

In this time of war, Lewis’s cautionary tale also reminds us that U.S. military entanglements overseas can have a profound impact on race relations stateside, and that communities of color are as vulnerable as ever to being targeted as “enemy aliens.” It bears remembering, too, that most of the major wars that the U.S. has fought in the 20th and 21st centuries have been against Asian antagonists, be they Filipino insurgents, Korean and Vietnamese communists, or Afghan “terrorists.” It’s impossible to overlook the towering presence of the military in the political, cultural, and economic landscape of the South. In order to grasp the complexities of East-South intersections, then, we must understand not only demographics and immigration patterns, but also the history of war and empire.

Although the United States did not directly intervene in the colonial wars and civil conflicts that devastated China in the mid-19th century, Lowe’s article traces the attempt of one group of white Southerners, missionaries from the Southern Baptist Convention, to capitalize on the social chaos unleashed by those wars in order to advance their own aggressive evangelical agenda. In “Scenes from a Forgotten War,” Christina Chia explores a now-obscure episode of Southern encounter with Asia through century-old photographs taken by soldiers and civilians during the early days of the American occupation of the Philippines. It is startling to see some of these photographs today, both for the global dimensions of Southern history that they reveal, and for their resemblance to images that have emerged from the occupation of Iraq.

If America’s military history has left its marks on Southerners, it also continues to touch the lives of Asians in the region. A complicated tale of love and a shifting notion of homeland, Dwayne Dixon’s story, “Mixing Blood,” Japanese women, all married to U.S. servicemen and living in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Estranged from their families in Japan as well as from the established Japanese professional community in North Carolina, these women’s identities and experiences have been uniquely shaped by Southern military culture.

It remains to be seen whether and how that culture will affect the Puih family, who are profiled in Hong-An Truong’s photo-essay, and other members of the small Montagnard community in Raleigh. Because they were allied with the Americans against the North Vietnamese during the U.S.-Vietnam conflict (and persecuted for it after the war), Montagnard refugees have a singular historical connection to the North Carolina military community, particularly veterans of the Special Forces. What part will that history of alliance play in their new lives as minorities in the U.S.?

Along with war, capitalism has been a motive force in bringing Asians to the South, and Southerners to Asia. The stories of 19th-century Chinese farm workers in the Mississippi Delta and contemporary Indian high tech guestworkers in the Research Triangle, while obviously different, are both chapters in the Western world’s tangled history with Asian labor. That history has taken a new turn in this age of globalization, as U.S. manufacturing jobs are steadily “outsourced” to Asia. This new development in East-South encounters are painfully evident here in North Carolina, where every month brings news of more textile factories closing, laying off local workers, and relocating to China. The largest retailer of Chinese-made products in America is the Arkansas-based Wal-Mart. By and large, mainstream media stories about globalization and labor have focused on the plight of American, usually white, workers. Operating with a neo-Cold War U.S.-versus-them logic, these stories pit sympathetic American laborers against a shadowy, faceless Asian (or Latin American) workforce. Thao Ha’s article, “Troubled Waters,” brings much-needed attention to the effects of “free trade” on working people of color in the U.S. who are already marginalized within their trades. Focusing on Vietnamese-American shrimpers along the Texas Gulf Coast, Ha shines a light on the economic hardship and personal anguish of a community buffeted by industry racism and neo-liberal trade policies that have put them in competition with shrimp farmers from the developing world, including their former home country, Viet Nam.

In one way or another, the stories we have gathered here are about the struggles and journeys of ordinary people caught up in the impersonal forces of history. We end the issue with perhaps the most personal piece—a deceptively simple story about friendship and cultural identity, told by a young Cambodian-American woman in an interview with Barbara Lau. Ran Kong’s story, while showing what we can learn just by engaging in conversation, also demonstrates that even among the younger generations of whites, blacks, Latinos, and Asians growing up together in a legally unsegregated South, we still have a long way to go.

Tags

Christina Chia

Christina Chia lived in Hong Kong and California before moving to Durham in 1994. She received her Ph.D.in English from. Duke University, where she has taught a range of courses on racial politics in U.S. literature and culture. Her research focuses on the intersections between different communities of color within the context of American racism and imperialism.

Hong-An Truong

Hong-An Truong is a photographer, visual artist, and writer working on issues that involve youth, education, and racism. As Documentary Arts Educator at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies (CDS), she coordinated youth education projects on community issues, and media activism. She has also taught undergraduate and continuing education courses on documentary photography and racial politics.