Beyond the Model Minority

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 33 No. 1/2, "East Meets South." Find more from that issue here.

Milan Pham is the Director of the Department of Human Rights and Relations in Orange County, North Carolina. This May East Meets South co-editors Hong-An Truong and Christina Chia sat down with Milan to talk about how Asian Americans fit into the South’s complex racial and cultural equations.

HONG-AN: Can you tell us a little bit about the affirmative action debate at UNC when you were a law student there?

MILAN: This was the time when Molly Corbett Broad started as the president of the UNC university system. She came from California, and on her heels Ward Connerly visited campus. He was one of the regents of the University of California system. He was the primary sponsor of Proposition 209, which is the proposition that dismantled affirmative action across California.

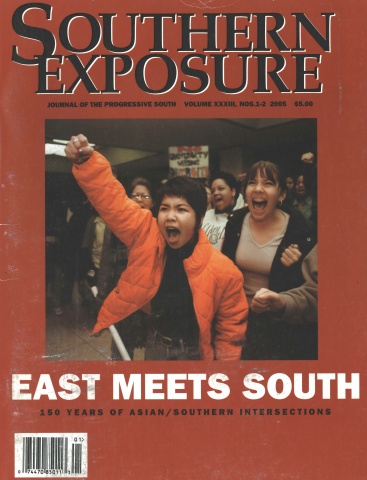

There are lots of issues, being Asian American, that concern me about affirmative action. In North Carolina particularly it’s that we aren’t qualified for affirmative action because we’re not considered minorities, even though we obviously are minorities. [Laughter.] It’s written all over our faces. So I, along with a group of other law students and the National Lawyers Guild, decided that we weren’t going to let him come quietly. And we organized with some of the undergraduate groups a huge protest against Ward Connerly. [The cover photograph shows Milan at this protest, in December 1997.-ed.]

[After Connerly’s visit,] we organized a debate on affirmative action. We brought in national folks—one person from the National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium, and the director of Americans for a Fair Chance, who also used to be the director of the Glass Ceiling Commission under Reagan. So we brought them in with a local person and then we let the Republicans bring in their people as well. They had John Hood from the John Locke Foundation [and] one completely inarticulate student, and that was their side. And it started a huge debate across campus about what UNC should be doing about affirmative action. But in the law school, I got a lot of backlash from Caucasians who were like, “What are you talking about? Affirmative action is for unqualified people. Your people don’t need affirmative action.” And so it was an exciting time but it was also really depressing.

HA: Can you talk a little bit more about Asian Americans being eligible for affirmative action in North Carolina? What defines “minority” in North Carolina?

M: Minority is defined as a group of people who can show historic discrimination. In North Carolina we haven’t proved that, at least not at the university level. And this is the thing that really kind of makes it clear that they know exactly what they’re doing. I mean, this is institutionalized racism: When it comes to counting their numbers for reporting out on affirmative action, they count us, but when it comes to qualifying for minority scholarships, they don’t count us.

The reason why I’ve even discovered this is when I went to law school I ended up having to take out a bunch of loans, which I just didn’t want to do because I wanted to work in public interest law and if you take out a bunch of loans you can’t afford to do that. So I wanted to get a minority presence grant at Carolina. I went to the dean of admissions, and she said to me, “Well honey, you have to be a minority!” (Laughter.)

CHRISTINA: Is Asian American a box you can check on the form?

M: Yes. It’s a kind of painful thing to watch happen. Latinos are considered minorities, but they envisioned a certain kind of Latino—someone of Mexican or Central American descent. Not every person with a Spanish name. Well, an intern who worked in the office where I was working decided that he was going to apply to law school. This is a person who had a Caucasian name and a Latino name. He had two drivers’ licenses, one reflecting his Caucasian name and one reflecting his Latino name. And everyone knew him by his Caucasian name. His family is from Spain. He applied, and was granted affirmative action benefits.

HA: So you can see how easily manipulated the system can be. But also your story epitomizes the struggle for Asian Americans organizing in North Carolina. Because if Asian Americans aren’t even recognized as being a group of people who have experienced and do experience cultural, social, and economic oppression and struggle, then where do you even begin?

M: Well, the North Carolina Asian Pacific Islander American Community Leadership Forum we had this weekend ended up being really useful. We had a speaker there named Jay Chaudhuri, who works at the attorney general’s office and works pretty heavily with Indian-American groups. My piece of the forum was to talk about the racialization of Asians, and why it was important for us to engage in pan-Asian organizing. After the forum Jay came up to me and said, “You know I never thought I needed to be engaged in pan-Asian organizing.” And I said, “When it comes down to it, whenever there’s an international incident, we’re all Sikhs, or we’re all South Asian, or we’re all Chinese. And what we identify as our ethnicity is not pertinent to Americans as a whole. You know, the spy plane fell down over China and everybody who looked remotely Asian became Chinese, and people were saying give us back our damn spy plane, like you could hide it in your back pocket. (Laughter.)

HA: Can you give a little bit of background on how [the forum] got started and who attended?

M: I guess it started about 2 years ago, in 2002, when Ben de Guzman, the community education manager from NAPALC [the National Asian Pacific American Legal Consortium], started coming down to North Carolina. I used to just call Ben and say angry things to him, you know, because there were no community partners [to NAPALC] in the Southeastern United States. I would call him and just berate him on his voice mail, until he finally called me back and he was like, “I don’t know who this bitch is, but I need to call her back!” (Laughter.)

He called me back and was like, “Okay, I don’t know what the problem is, but let’s try to figure something out.” And I said, “We have a growing population down here, and there are no services to us. And in North Carolina no politicians are talking about serving the APIA community, and even our advocates are not talking about us. Here we are growing by leaps and bounds in the Southeastern United States—like, the home of Racism Incorporated!”

He slowly started sending people our way. When Helen Zia [journalist, historian, and author of Asian-American Dreams] was coming through, we met with her. And then [de Guzman] started looking for money to put on something in this area—to funnel money through NAPALC to North Carolina, which is how we got the forum.

HA: Who attended?

M: There were all local people except for Ben, who spoke on national policy issues. We also had a leadership development session from Leadership Education for Asian Pacifies which is out of California. There were about 35 people there. All heads of organizations, like NAAAP [National Association of Asian American Professionals], TACAS (Triangle Area Chinese-American Society], the North Carolina Chinese Business Association, and the Hmong National Development, North Carolina Chapter. So it was good. A lot of people were like, “We just had no idea that these are issues for our community.”

C: You mentioned that there were a couple of national groups or California-based groups that came to present [at the forum]. What are some issues that are unique to this area that maybe people in those other regions aren’t aware of? Do you feel that there’s a way that people in California are used to thinking about issues, that doesn’t work here?

M: I guess the issues that are really unique to this area aren’t really quantifiable as issues. Some of the things that are unique to this area are things like, the local population is the population that you really have to rely on in order to get the work done. Asian Americans who come in from other places also leave, because they come in and find there’s no infrastructure, which makes it very different from the Washington D.C.’s, New Yorks and Californias. People from Washington and California come in, with the exception of Ben, and think, why don’t these people just get on the ball already and do something? Well, there’s completely no infrastructure here to do anything. And we’re having to start with educating funders that we’re a community in need.

I had a really disturbing conversation with a funder once where he was like, “Your people don’t need help!” And he pulled out a News and Observer article that said that Indian Americans were taking the best jobs in the Triangle as his evidence. And I was like, “Okay there are 49 other countries of origin for us. Do you have an article for each of them?”

One of the things that has been a real difficulty is that local folks by and large don’t tend to get onto the organizing band wagon until they’re well into their 20s—after they’re out of college and they hit the workforce. That’s when they finally begin to see that there are real differences and they’re being treated differently. So in college, when other people are beginning to organize, Asian Americans, if they’re organizing, will go to the women’s groups, or the African American groups, or the economic justice groups, and organize there. Mostly because we don’t have infrastructure except for ASA and they’re kind of like the dumplings and dragon dances kind of group, you know? (Laughter.)

So our organizing curve is a little bit behind everybody else’s as well. I mean those are our difficulties. Our issues are the same as everyone else’s issues across the country, just more magnified because there’s nothing being done, or at least what is being done is not staffed. It’s being done by a bunch of volunteers so there’s nobody who’s committing all of their time to doing work. You know, these are people who have worked 8-10 hours already and they come home and they’re like I need to get on this press release for ANCAPA [Advocates for North Carolina Asian Pacific Americans]. That’s tiring work.

HA: Do you feel after this meeting that there is a lot of potential? How do you feel like the community leaders were responding to the discussions about the need for Pan-Asian organizing and organizing for APIAs in North Carolina period?

M: I think they responded pretty well. I mean most of them are by choice non-political. They’ve had the discussion; they don’t want to rock the boat; they want somebody to do it, but they don’t want to be the ones. So at this point, they’re happy [to say], “Oh we’ll just let her do it. We’ll come and we’ll help and we’ll give money, as much as we can, and then we’ll let her and her people handle it.” Which is okay, as long as they’re willing to provide the bodies and the money. That’s fine by me. I don’t want someone who’s avowedly unpolitical trying to forward a political agenda. That’s never going to work.

I had a friend of mine who’s a videographer come videotape the [forum] and we’re going to create a DVD of the policy piece—the national policy piece which frames the North Carolina piece—and we’re going make enough copies to distribute to every locally elected official in the area, at least in the Triangle, to say, “You know, you have to be responsive here to our community. Because our community is growing in these ways.”

HA: So why do you think that is that some of these cultural and business organizations tend to want to stay apolitical, or try to not rock the boat?

M: I think by and large it has to do with our immigration patterns to the United States. I mean most of the cultural and business organizations are run by, at this point, immigrants to the United States, and not their children. And that I think makes a huge difference in the way that they see what’s happening.

For every immigrant who lives substantially in another country, the United States is just so much better than anything that you could imagine. So it really takes an American to be talking—I mean an American, someone who was raised here, someone who has the expectations and the entitlements of an American—to be talking about what racism looks like in America. Right now, most of our community organizations are run by foreign nationals.

C: And that’s probably particular to the South just because there haven’t been the generations of immigrations, third, fourth, fifth generations, of Asian Americans here.

M: So we’re waiting for the Hong-Ans and the Chris’s to finish their studies and head up organizations. I mean that’s when you’ll begin to see this conversation growing. Either there are people like us who begin to head up Asian organizations or we’ll get into places where we can advance our agenda. I don’t work for an Asian organization but I can leverage the power of government to talk about our issues.

C: So you’ve been talking mostly about how to educate and get government entities and the media invested or even interested in APIA issues. I was wondering how you feel about the state of the conversation between you guys and other community groups who have a longer history in this area. What’s that conversation like?

M: Well, I feel like until we have our act a little bit more together, we’re probably not really suitable to be talking about coalitioning. I think we have to have a little bit of stability in our house before we’re like, okay, let’s make a neighborhood. Because I think that that creates danger for other groups that don’t necessarily need it. Even though the Latino community is a little bit more organized than us, and the African American community, there are still lots of issues in those communities. What I don’t want to bring to the table is just a bunch of problems and nothing to contribute for other organizers who are struggling already.

I think it’s important to coalition with other people of color, but it’s not time yet. I also think that within other people of color communities, as well as within the API community, there isn’t a real understanding of the belonging to the people of color umbrella. Asian and Pacific Islanders are having a hard enough time identifying as Asian. Just imagine going beyond that and saying, “Okay, you’re not Asian, you’re a person of color.” [This is] vocabulary and terminology for people who have been working for a while on these issues and have done all their own personal work in addition to the work of the movement. So I don’t think we’re there yet. And that’s not saying anything about how intelligent or qualified or organized our community is—it’s just part of our development. The southeastern United States is not there yet.

HA: A lot of the stuff that you guys were talking about at the forum was on the policy level, so how does that kind of work happen?

M: Well, Ben and I specifically decided to kind of keep away from “people of color” organizing. He did kind of throw in a plug for [it as well as] LGBT organizing and the intersectionality of multiple oppressions and then suddenly you could see the glaze. I mean, it was like a Krispy Kreme doughnut! (Laughter.)

Ben talked about immigration-related issues, which I think will be impacting our area pretty heavily. He also talked about the Real ID Act, and how that will be impacting our area pretty substantially as well. We talked about more concrete things, laws and policies that exist or don’t exist to help our community. I identified our top three issues as number one: Community Capacity Building. By that I mean getting elected officials who represent our issues, having organizations that are funded and engaged in organizing, and doing things like getting Asian American Studies in our universities. There are lots of things that could happen in the budget process, you could have money ear-marked to go to certain non-profits if you can do work with your legislatures.

The second most important issue was Language Access, because our community is so largely immigrant. Forty-six percent of our communities don’t speak English well. They’re considered linguistically isolated, no matter their country of origin, which means they’re not accessing any of the services that help move people from lower economic class to middle class.

And the third most important issue was Affirmative Action. And that is because our community is growing, and because we’re in the process of setting up infrastructure for the APIA community here, we really need access to affirmative action programs like minority contracting programs. One of the first people who contacted us at ANCAPA was a business owner in Durham who didn’t qualify for any of those small business administration loans. He wanted to run a printing business, and they told him he wasn’t a minority. And he was like, “Look around! Do you see any other Asian people here?” So I think it’s really important.

With our growing immigrant population a lot of that population is not going to be the more affluent, more educated Asian American community. We’re going to have much more needy immigrant populations, and we’re going to look more like the Latino community. That’s what happened in California, and they had to set up their community centers to deliver social services-- that’s what happened in New York, that’s what happened in Washington D.C.

C: Can you talk a little more about the Real ID program? You mentioned that Ben talked about the impact of those programs on communities here. Could you elaborate on that?

M: The Real ID Act basically establishes a national ID. North Carolina is one of the few states where you can get a driver’s license without being a citizen. What this would require is all kinds of proof of citizenship in order to get a driver’s license. As you can imagine, it’s not quite as easy for Asians to immigrate illegally to the United States. But a lot of what people do is that they come over on student visas or work visas and they stay. And that’s particularly true in our area—heavy with IT corporations, heavy with universities. So what Ben said is that we’re going to begin to see a flood of folks who are now unable to either renew their driver’s licenses or get driver’s licenses and those people will begin to show up in the criminal justice system, which is probably where we’ll see them first. And it’s really disconcerting because it’s a way for the BCIS [Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services] to identify people they might label as potential terrorists—and then deport them summarily.

HA: So switching topics a bit, back to local organizing. Chris, you work at the Multicultural Center at Duke. What does your job entail?

C: It basically works with students of color at Duke and actually the position that I’m going to be holding for the year is one that is relatively new. It’s primarily geared towards working with Asian American students.

M: I think that it’s really important, and I’m glad to know that you’re working there, Chris, because we have an ongoing project with NAPALC to work with Asian student groups. But this is what Ben said to the entire audience of people, some of whom were potentially transient, he said, “If you leave you’re just a bunch of chicken shits.” (Laughter.) He said, “You know if you want to do the real work, the groundbreaking work for APIAs, it’s not in California. It’s not in Washington, and it’s not in New York. Been there, done that, everyone’s done everything over there. The groundbreaking work is here in North Carolina with this group of 35 folks, whether or not you want to admit it.”

HA: I think that’s true. It’s exciting. I alternate between feeling really depressed, and then have moments of feeling that we’re getting somewhere.

C: There are a couple of faculty people over at Duke who are interested in Asian American Studies and we are going to have a series of monthly meetings. We’re going to talk to folks at UNC and have some kind of event to talk about Asian American Studies in the South. In a way the issues on the policy level that you mentioned are the same issues on the university level. So it’s the administrators are reluctant to start anything with Asian American Studies. They’re kind of like, well, why do you need it? We’re sort of already redressing the question of African American Studies and we don’t need anything else, right? So it’s kind of this weird zero-sum thing.

M: One of the things Ben said that he thought was really interesting about this area is that the students weren’t the primary driving force for starting ASAs and Asian American Studies departments. It was the community, the community of professors and academics and other community folks who were like, “We need Asian American Studies.” And I told Ben, “Well the reason why that is is because it takes people until they’re out of college here to figure out that they’re not white!” Because the way our academic systems are set up, you hear about African Americans in the South, and then you hear about their tyrannical oppressors, and you don’t hear anything else about anybody else. I mean, we don’t even hear about Che Guevara around here. (Laughter.) So you’re like, “I’m definitely not African American, so I must belong to this other group.” And so it takes us until [we’re] out of college to figure out that we’re not white. The coming out process for Asian Americans here is really quite long!”

Tags

Milan Pham

Milan Pham is the Director of the Department of Human Rights and Relations in Orange County, North Carolina. (2005)

Hong-An Truong

Hong-An Truong is a photographer, visual artist, and writer working on issues that involve youth, education, and racism. As Documentary Arts Educator at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies (CDS), she coordinated youth education projects on community issues, and media activism. She has also taught undergraduate and continuing education courses on documentary photography and racial politics.

Christina Chia

Christina Chia lived in Hong Kong and California before moving to Durham in 1994. She received her Ph.D.in English from. Duke University, where she has taught a range of courses on racial politics in U.S. literature and culture. Her research focuses on the intersections between different communities of color within the context of American racism and imperialism.