Diary of a Poultry Worker: Javier Lopez

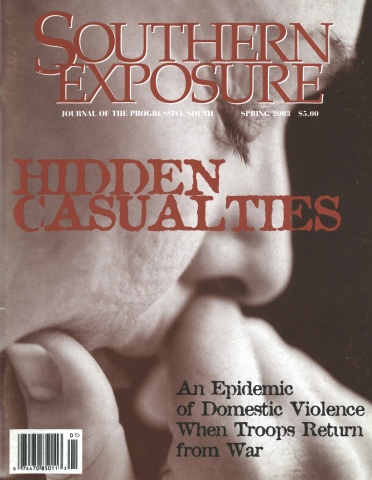

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 31 No. 1, "Hidden Casualties." Find more from that issue here.

I sort chicken parts in a factory in Duplin County, North Carolina. There’s a lot of poultry in this area. I don’t want to say the name of the company I work for, but you can use my real name because I’m not legally here in this country anyway. No one knows I’m here.

I work the night shift. The second shift. It starts at ten-thirty p.m. It’s supposed to go until eight a.m., but sometimes we can go on till nine or ten. Sometimes till noon. It depends on whether we get our chickens done.

The chickens come from South Carolina. They slaughter them down there and then they cut them with machines. Everything is used. They’re de-feathered, they cut off the feet, they’re de-headed and de-necked—and they grind that in a mill and turn it into chicken feed. The rest they ship up here to us in trucks. We sort the parts. There’s around thirty-five thousand chickens per truck.

I work in Department 20 with about a thousand other people. It’s equally divided between men and women. Our job is to separate the wings, legs, and breasts. We also do some de-boning. After we separate, another department packages the chickens and sorts them by weight. Then another department labels them and packs them in crates and stamps them for shipping. I don’t know where it goes when it leaves here. I think supermarkets, restaurants maybe.

I just cut up and sort chickens. That’s my job. It’s cold on the hands. It’s hard on your health, because outside it’s hot, but inside, the temperature has to be under fifty degrees. We get sick all year round even if we dress warm. Ice is always falling from the ceiling on your head. Some of it gets on your feet, into your boots. Your back’s always cold, and your feet are always wet.

There used to be mats on the floor, so your feet were not in the mess on the floor. But management eliminated them because there was an accident. A woman stumbled on them. Now there is water on the floor, and your feet are always wet. My boots are always cold. Some people use sneakers but those are worse. They get wet and damp, which makes it colder. Then there are the fans that just blast away all the time, making everything more cold.

You have to be careful with the knives and the machines, because everything is so slippery. A lot of fat falls on the machines and the floor. There’s fat everywhere. Everything’s greasy. So, especially when you cut the wings, you know, there’s a disk cutter with a rotating blade, so your fingers are in danger. And if you cut yourself, you’re going to get very contaminated from bacteria in the chickens because before you cook them, the raw chickens are full of bacteria.

I work very fast, and I’m not always checking what I’m doing, even while I’m doing dangerous work like de-boning with the disk saws. We are slaves. They don’t care. If we are not done with the truck full of chickens, we cannot leave work at the end of our shift. Sometimes it’s because of mechanical breakdowns, machinery malfunction, nothing that we did, but it doesn’t matter. We can’t leave. They don’t care how long you work. You just have to be very fast. So you’re not always working safely because you have to keep up with the production line. Of course, the managers always want more production in less time. It’s pretty tiring.

There is no support, no help. If a worker gets behind and doesn’t keep up with the line, out they go! Much injustice, no support. The supervisor is always right, the worker is just—there. Music is forbidden, so is talking with other workers, but we still do it. Yes, we do it. But I don’t say a lot myself. I am a quiet person.

I have been here seven months. I earned five dollars and eighty-five cents an hour when I started. After three months, they raised me up to six twenty-five.

I don’t like this chicken work. I used to work in the fields, picking fruit, tobacco. I like that better. In the field, you know that you can always make your quota, sometimes by twelve or two. So sometimes you have the afternoon free. It has disadvantages—if it rains or the crop is bad, maybe you have no money. But when it is good you can make double the money. It’s better. And maybe you get some fruit too, to eat or take home. Here, they don’t even give you chickens. If I wanted some, I would have to buy them. (Laughs.) But to be honest, I have no desire anymore to eat chicken.

It’s pretty disgusting to work with meat all the time. The factory smells very, very bad. There is a lot of bacteria. Everything is a mess. There are broken windows, and there’s no security or safety at all. Anybody can come in at night. There’s a guard, but he’s asleep half the time, and he doesn’t care. Where is the safety? We have talked with the higher people but nothing happens. In many cases there are two thefts per week in the parking lot. They said they were going to hire a policeman. But they don’t.

The company wants everything for themselves, and nothing for the workers. You have to buy your boots, aprons, and gloves. Boots are ten dollars. Gloves cost fifty cents and aprons cost four dollars and fifty cents. That’s a lot when you’re only making six twenty-five per hour. Why should they make us buy this equipment?

I have heard that some of the poultry plants are better. This is apparently one of the worst ones. If you want to go to the bathroom, it’s very difficult. Even if you need to go you have to wait for break time and there are only two breaks per shift, and you have to eat during them. And the breaks last for half an hour each, but in reality they are less than twenty-five minutes because you have to dress and undress the gloves and things like that. They take this time away, and it’s important because if you’re going to eat, and go to the cafeteria, you still want to wash up before you go. But for the men there are only two toilets, so you have to wait in line. It takes at least five minutes to get into the bathroom just to wash your hands. And it is completely dirty and disgusting. There’s so much chlorine all over the place, it stings. It hurts your skin, your eyes burn.

Then there is the food. The “cafeteria”—and I call it that between quotes—is disgusting. They feed you chicken, chicken, chicken. It’s not good or clean there. Where you eat, it is unfortunately dark, smoky. People complain, but like with everything else, there is no discipline about cleanliness. Smoking should be done outside because the cafeteria is for eating. But there is no discipline, no respect. Nothing.

Another thing—racism. The large majority of workers here are illegal Hispanics, like me. There’s also some legal Hispanics, some Haitians and black gringos. But most of us are illegal Hispanics. The bosses know we’re illegal, and it’s illegal for them to hire us, but we’re the cheapest, so they don’t care. We probably wouldn’t work such a bad job if we had documents. And they always yell at us Hispanos. With the others they are more flexible, more lenient. The others come late sometimes, they talk on the phone. And they can get away with it. The black gringos that work here have more flexibility, they speak English. The blacks talk back, and they can argue because they speak English.

There are many druggies among the workers—a lot of marijuana. Lots of drugs and drinking—especially among the darker workers. But whenever something happens it is always blamed on us, the “Hispanos,” and the reputation of our race is affected. Every time, we all pay with our reputations. We never get a foothold, and they always stomp on us.

There is no better worker than the Hispanic. We work any hours, others don’t. But even if we work harder, because we have no papers and no English, we unfortunately get the worst deal.

I’m from Mexico, Veracruz. I paid a “coyote” to bring me here—that’s what we call the guides. It cost me one thousand and two hundred dollars. To come you have to cross a desert, so it is pretty hard, and it is dangerous. It takes four days and three nights and you can’t get out of the truck. You can’t stop. You are in these trucks, packed just like sardines, very tight, and the trucks keep moving and turning around with us inside. If you did not bring your own water you are thirsty. You cannot stand up, you cannot do anything, except lie on your side and the person next to you puts their feet where your head is. It is very hard and very tiring to get to the U.S., to make this sacrifice to look for the “golden dream,” the dream of all people. People say they are coming to the U.S. to make money, but many go back when they arrive here and see what awaits. They cannot stand it here.

The coyote brought us straight to the work contractors who hire us and then the farmers hire us from them. A farmer brought me up to North Carolina from Texas. I was lucky because he paid me right. Sometimes they might say, “If you come with me, I will pay you one-fifty per week,” or something like that, then at the end of the week they tell you, “Here, take twenty dollars.” And when you complain and you say, “I need this for money for my family,” they say, “No, you owe me this and that” for gas and various things and you don’t get any money. Then you have nothing. You have no money, you don’t speak the language, and you don’t know anybody. You are lost. So I was lucky because I got paid right.

I’m hoping to eventually go home and start a business. I don’t want a boss. I am ambitious to a certain extent. I want to plan and achieve something. Working for someone else—there is nothing. You need a goal. Many don’t have one, don’t think about tomorrow. I have plans.

By tightening a little, and living squished, you can save a little. We have five people in my little house. It is not comfortable, we live one on top of the other, we share one car, but I save my money. And the exchange rate is good if you are paid in dollars. You have to sacrifice, not be comfortable, or you will not make it.

They pay us once a week by check. You can’t open a bank account without a Social Security number, so it’s a little difficult. You can cash the check in the company bank as long as you do it within twenty days. Many people go to some Mexicans, a service they run, but they charge a percentage, sometimes two percent. It’s a lot to me. There are also a lot of thefts—people break into our houses and steal our money, because they know we can’t keep our money in banks. It’s all cash. That has been happening a lot lately. And in the parking lot, sometimes on payday, people steal the checks. Then you need to get a replacement and they make you wait a month to make sure it hasn’t been cashed. So then you’re without money.

That parking lot is the worst. There is no security or safety there. When we go to our cars, there is a constant risk of being robbed and killed, you know, for maybe one hundred and fifty dollars. We have no security eating, sleeping or working.

There was a case, about a month ago, where I was working inside and a boy near me went to this door outside to throw the garbage out and there was a man out there, another worker, who asked for a cigarette. The boy had none to give him. The man had a knife, one of the ones they give us to cut the backs of the chickens. He stuck the boy with it. He stuck him so hard that the knife, which is made of steel, got bent. The boy couldn’t talk, and he was bleeding, and he was scared. Somehow, though, he got the knife away from the other guy before he cut his throat. They took him to the hospital. The police came and they knew who had done it, but they didn’t do anything about it. No one cares.

I’m thirty years old. Too old for this kind of stuff. (Laughs.)

I am far from family, alone, thinking a lot. I have nothing. That’s what I think about. I have nothing. I thought in the United States one lives a life of luxury, dressing well, partying, and all that stuff. You don’t know the reality of it till you come here. It isn’t the life one hoped for. It is pretty bad. It is not what I thought. People back home can’t imagine that we don’t have the comforts they think we do. The people I know here, the illegals, we are without our families from five years sometimes. I haven’t seen mine for a whole year. I miss them. We hope to be together, but I can’t just say, “I’m off.” I can’t go back. It costs a lot to come here.

I’ve never had anything. I have always been poor. So I have this mentality that even if you have nothing, you still have to be proud of yourself. I would like to think, “I am poor but I did this. I achieved this.” I want to be proud of myself. This is a more clear satisfaction to me, more than owning a car.

Hear that? (Laughs.) That’s a chicken truck. That’s probably the one going to my factory tonight. That’s what I’ll be working on tonight.

This article is an expanded version of an interview published in Gig: Americans Talk About Their Jobs at the Turn of the Millennium (Crown, 2000), edited by John Bowe, Marisa Bowe, Sabin Streeter, and Rose Kernochan.