This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

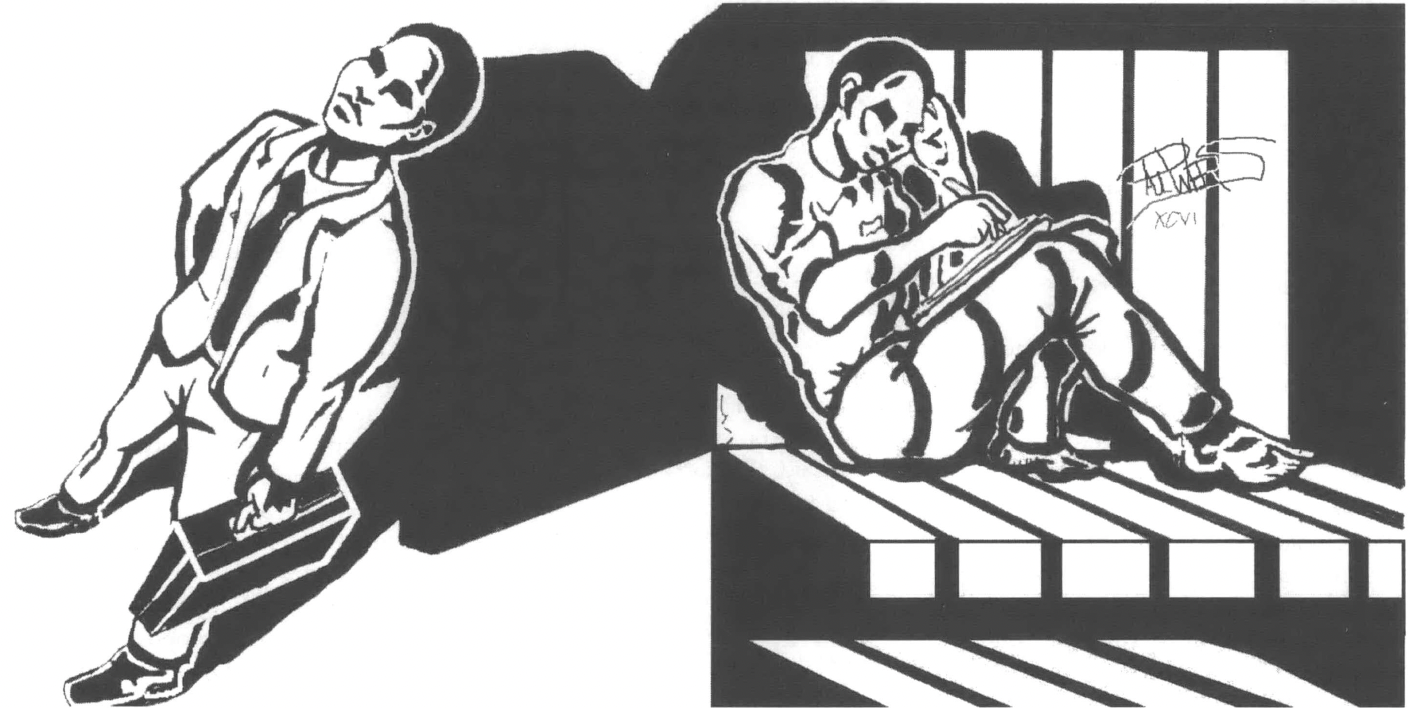

For a long time, I believed (privately, lest someone accuse me of simply attempting to exculpate my 25 year criminal career) that the untrammeled racism most blacks face on a daily basis in America was, at least in part, responsible for my blatant and repeated breaking of the social contract we are all responsible for upholding. I avidly read the theories vis-à-vis crime, punishment, and their attendant violence. Reading helped me escape the vacuum all convicts live in while allowing me to deepen my understanding of the cutting-edge issues facing my race. By extension, and perhaps by fate, I have also used my incarceration in the gently rolling hills of Kentucky to embark upon a nascent writing career.

Naturally, I studied the writings of national black newspaper columnists. They — while having an excellent grasp of the problems of the underclass — always seemed to fall short on workable solutions. I felt I could do better since I not only shared the black skin of those who posed to America its greatest social conundrum; I also shared lifestyles with them — I was “down by law.”

Whenever I would read a particularly incisive article — or one which I felt missed the mark entirely — I would write to the author of the piece. Realizing how convicts are viewed by the populace, I made sure that my missives were as free from errors as I hoped they were germane to the issue I was writing about. I never personalized my comments never carped or complained about my incarceration — the fact being I was as guilty as hell and probably deserved more time than I received for the years of credit card fraud I committed. I asked for nothing more than an enlightened exchange of ideas. After all, I was one of the people they were writing about. They wanted to hear from me. So I thought.

Later, waiting at mail call for letters that never came, I thought of how busy they must be coming up with fresh columns every few days and answering all the mail they received from those still at liberty with whom they undoubtedly felt more comfortable corresponding.

Undeterred, when the 1994 Crime Bill was being debated, I wrote to every member of the Congressional Black Caucus. I imagined that my 15 felony arrests and five convictions made me something of an expert on the subject. Again, no response. Since I couldn’t vote, why should a politician waste a stamp on the likes of me? I did get a nice letter from Arlen Specter, the Republican senator from Pennsylvania. Must be my situation, I thought.

It then hit me that I’d been attempting to establish dialogue with the wrong people. The individuals I should have been writing were the passionate magazine and book writers who, in a recent spate of publishing activity, had been taking moral stands on the issues facing black Americans of the underclass. I managed, by hook or by crook, to obtain copies of as much of their work as possible. After much feverish reading, I wrote what I thought were excellent letters appropriately praising them for what I thought they had right and posing questions or offering opinions whenever I thought they were wrong. I tantalizingly made reference to information and insights to which my situation made me privy. The response — nonexistent. Nada. Zip. Zilch.

My one out of two hundred or so batting average on replies to my letters (and that single letter from a white moderate) led me to an inescapable conclusion. First, even I can’t write so badly that only one person would respond, so my experience shows that middle-class black writers have fallen victim to the same malady their white liberal counterparts suffer. They have been infected by “arms-length liberalism.” They might champion the underclass, but they want nothing to do with them. They write passionately about the wrongs perpetrated by our racist society and how it marginalizes the have-nots, but they wouldn’t care to live next door to the have-nots and, evidently, would not even correspond with them. My experience, unfortunately, isn’t unique. There is a discernible pattern which I discovered talking to other convicts about their experiences with the outside world.

What is happening is a carry-over from Reconstruction. During that period, whites promised newly freed blacks better treatment if they dissociated themselves from their poorer, less educated brothers and sisters. The favored ones were urged to disown the “bad niggers.” This “divide and conquer” tactic has proven its utility even into the present day where we find half of the black community moving into what they think will be middle-class parity with whites while the other half is mired — and daily sinking deeper — into poverty, crime, drug abuse and violent self-destruction.

In his turn of the century book, The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. DuBois wrote that races advance when exceptional members advance and then reach back to bring their duller and less gifted brothers and sisters up to their vantage point. Sadly, this is seldom the case in the black community. As blacks move into the middle class, they are often more assiduous in their dissociation from the less advantaged of the race than are whites. History does not provide evidence of any race making real advancements piecemeal, half moving ahead and half staying behind. This moral blind spot of the black middle class is, more than anything, responsible for the sorry state of the civil rights movement today. Even during the 1960s and ’70s, when seemingly great strides were being made, the black underclass was largely ignored. The collapse of gains in recent years is proof that the movement did not include all blacks and therefore had no solid moral base.

The seeming intransigence of the underclass is due largely to the fact that the very people who are afflicted are effectively shut out of the solution formulation process. In early 1994, the country’s leading blacks convened a national conference on crime. Not a criminal or former criminal was to be seen. Few, if any, poor people were invited. Missing was the understanding that if the problems of the underclass are going to be successfully addressed, then those suffering the problems must be a part of the solution process.

One astute black female politician recently stated that “building prisons to solve the problem of crime is like building cemeteries to solve the problems of AIDS.” The country is moving closer and closer to permanent warehousing of a large segment of the underclass — black males. Young black men are going to prison for petty drug crimes that white youth have trouble getting arrested for, a phenomenon many feel is a strong case for “unconscious genocide.” Yet, the small and growing cadre of black conservatives applaud, along with racist whites, the ratcheting down on poorer blacks by police who blatantly practice selective enforcement of the law. The failure to protect the rights of all blacks — even those accused of crimes — ultimately results in society failing to respect the rights of any blacks.

As they move into the middle class, many blacks, knowingly or not, adopt the mores of the majority culture — the good and the bad aspects of it. The disgusting “arms-length liberalism” practiced by whites for years is now practiced by blacks on blacks. Within the black community, professional civil rights workers, political leaders, and writers have emerged. They eloquently complain and lay blame about the conditions of the underclass, but for them problem solving would conflict with their long-term self interests — how they make their living. Our mindless pursuit of integration as the road to equality has cost us precious time and valuable energy for what is, at this juncture, an unattainable goal. While it is certainly true that the problems of blacks in America are of white construct — white racism is responsible for the wretched conditions found in black ghettos — it does not necessarily follow that white society will solve these problems.

As much as I detest the appeasing tone of Booker T. Washington’s ideology — the promise not to push for full rights if blacks are allowed to prosper in the service industries — prison has made me acutely aware of the need to develop the strong craftsmanship Washington advocated. By failing to step in and take care of the youth who are so unfortunate as to be born to parents who don’t have the skills to steer them in the right direction, we, the black community as a whole, are producing a generation of youth without viable alternatives to lives of crime and prison. They join gangs seeking “somebodiness.” It does little to declaim that many parents are not doing their job. We have to mount efforts to save these children. We have to make every black child the responsibility of the whole black race.

For too long, blacks have held that the problems of our race should be worked out in private, that we shouldn’t “wash our dirty linen in public.” The end result is that a lot of black middle-class closets are overflowing with dirty linen. If remaining silent in public would cause action in private, I would remain silent. Castigating my own brothers and sisters is no fun. But silence has only provided cover for blacks who loudly proclaim to be champions of the underclass while building careers on the backs of the poor and the incarcerated. Enough, I say.

Enough of these two-faced fools, these educated ignoramuses, these “arms-length liberals” doing sad parodies of their brie-nibbling white counterparts. Enough of black elected officials who will sell out any birthright for personal or political gain. In the rise of a new breed of sellouts, we are seeing some who have been elected by promising what white politicians cannot — such as keeping black children off the buses which bring school integration, a tactic made even more invidious by a failure to insure parity in the separate school programs. And black writers have been giving these officials a free ride. Shame. Shame.

Inevitably, middle-class blacks bump their heads on the low ceilings of corporate racism and discover that the promise of equality and parity in a white-controlled corporate world is a placating lie and pernicious myth. Embittered and disillusioned, they begin the long journey back to their roots. Ellis Cose, in his seminal book The Rage of the Privileged Class, documents what these upwardly mobile blacks are up against and the anger they feel over not being able to overcome. The fancy titles of “Vice-President of Minority Affairs” or “Corporate Compliance Director” prove to be empty positions which actually mean “Head Nigger in Charge of Nothing.” The Faustian bargains they strike — to remain silent about the racism they see around them daily in return for personal gain — unravel around their ears.

And we, we blacks of the supposedly “lower” classes, who could have told them that it was all a trick, must welcome them back even though they turned their backs on us the moment they thought they had escaped. We can show them we are bigger than they are in heart, spirit, and soul. We need them. They have skills which can create new wealth and assist in utilizing the wealth which already exists in the black community. And they need us. We are their poor, their criminal, their addicted brothers and sisters, and the race will not, nay, cannot be lifted up until — and unless — we are lifted up, too. We are for better or worse all in this cauldron, which is white America, together, and we will rise or fall as one race . . . together. Peace . . . be still.

Tags

Mansfield B. Frazier

Mansfield B. Frazier started writing seriously while incarcerated at the Federal Correction Institution at Ashland, Kentucky. In 1995, around the same time as his release from prison, his first collection of essays, From Behind The Wall: Commentary On Crime, Punishment, Race, and the Underclass by a Prison Inmate, was published by Paragon House.