This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

For five centuries, the Choctaw Indians lived and worked in the lower delta of the Mississippi River. Using simple bone and wood tools, they fished, hunted, and planted corn and beans in the fertile soil, sustaining their own families and trading excess crops with neighboring tribes.

All that began to change with the arrival of Hernando de Soto in 1540. Spanish soldiers killed more than 2,000 Choctaws in their search for gold and slaves. In the centuries that followed, other European settlers steadily overran tribal lands. By 1831, federal troops had forced 18,000 Choctaws to leave their homeland and relocate in Oklahoma.

Today, the descendants of Choctaws remaining in Mississippi face a threat almost as deadly as Spanish conquistadors and U.S. troops. In 1991, tribal chief Phillip Martin invited National Disposal Systems, Inc. to build a hazardous waste landfill on tribal land.

"Just because we're a minority group, they thought our land could be used," says Linda Farve, president of Concerned Citizens of Choctaw, which resisted the landfill. "We've been taught by our ancestors that people's health was important, never that money was the important thing in life." Last year, 60 percent of the Choctaw people voted in a referendum to reject the landfill.

The connection with their tribal history was not lost on most Choctaws. The proposed landfill, say Scott Morrison and Leanne Howe, represented "the culmination of all the foreign diseases, concepts, and institutions introduced since Columbus landed that have paved the way for the waste crisis in 1992." Since the arrival of European explorers in the South, the exploitation of Native Americans and other people of color - racism - has been tightly interwoven with the exploitation of the environment in which they live and work. Native Southerners, African slaves, and migrant workers provided the land and labor that formed the backbone of Southern industrialization. Today, polluting industries continue to take advantage of the poverty and powerlessness of people of color - employing them in toxic jobs and dumping hazardous waste in their communities.

Known as "environmental racism," this new pattern represents an old way of doing business in the South. According to a 1987 study by the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, half of all Native and Asian Americans-and three out of five African and Hispanic Americans - live in communities with waste dumps.

Dumping on communities of color has become a big business. WMX, the largest waste management corporation in the world, is expected to bring in $10 million this year from its toxic waste sites, including those in predominantly black Southern towns like Port Arthur, Texas and Emelle, Alabama (see "The Emelle Megadump," page 17).

But in recent years a new movement has emerged, led by people of color at the grassroots level. Sparked by the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, the community-based movement has helped strengthen local activism across the region, placing the struggle to defend the environment within the larger struggle for social and economic justice.

"The issue of environmental racism in our communities has become an issue of life and death," said Benjamin Chavis, then-director of the UCC Commission for Racial Justice and now executive director of the NAACP, in his opening remarks at the summit. "It is our intention to build an effective multiracial, inclusive environmental movement with the capacity to transform the political landscape of this nation."

Disease and Dumps

The first Southerners to experience environmental racism were Native Americans. Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, Tuscaroras, Catawbas, Seminioles, Natchez, and other Southern Indians who inhabited the region long before Columbus lived in complex, self-sustaining communities. Many cultures took only what they needed from the environment, leaving the soil and forest to replenish after they planted and hunted.

“When we speak of land, we are not speaking of property, territory, or even a piece of ground upon which our houses sit and our crops are grown,” explained Jimmie Durham, a Cherokee who fought a dam slated for his reservation in the 1950s. “We are speaking of something truly sacred.”

The Europeans who invaded the South beginning in the 1500s treated the land and its people much differently. In European culture, man controlled nature, and land and natural resources could be bought and sold. While some Europeans defended Native American rights to their homelands, many saw them as nothing more than “wild and cruell Pagans,” and used their “inferior” race and “primitive” culture as an excuse to plunder land resources.

Warfare, alcohol, and European diseases like smallpox and typhoid decimated entire native populations. In 1763, one English general even proposed a kind of germ warfare: “Inoculate the Indians, by means of [infected] blankets to Extirpate this Execrable Race.”

Throughout the next two centuries, Europeans continued to use the race and culture of Native Americans as an excuse to take and develop their land. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, the expansion of Southern agriculture, and the discovery of gold in Georgia, seizing Indian land became national policy. In 1829, President Andrew Jackson called for Southern Indians to be moved west. Despite appeals from tribal representatives to stop the removal, government agents forced tens of thousands of native Southerners to leave their land. The Cherokees alone lost about 4,000 people on the 800-mile march to Oklahoma which earned its name, “the Trail of Tears.”

A series of federal acts between 1871 and 1934 deprived the surviving Indians of much of their remaining land and sovereign power, replacing tribal governments with councils overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Nevertheless, relocated Indian nations have retained full sovereignty when it comes to the environment. Federal environmental protection acts passed in the 1960s and 1970s include no provisions for indigenous lands, and the BIA has neither the staff nor the resources to evaluate and monitor waste facilities. Some nations have established their own environmental protection agencies, but many lack the resources to defend their air, land, and water .

The lack of environmental protection in Indian territories - combined with widespread poverty and high unemployment - has made native land an attractive target for the military and waste companies. According to federal reports, 650 solid waste disposal sites and two million tons of radioactive uranium now contaminate Indian territory across the U.S.

And the dollars-for-dumping deals continue. In recent years, the U.S. Department of Energy has gone from tribe to tribe, offering up to $5 million in exchange for storing deadly uranium tailings in Monitored Retrieval Storage sites. "This is the space-age version of the diseased blankets deliberately given to Indian people by the U.S. Cavalry," says Navajo Valerie Taliman.

But without viable economic alternatives, many Native American communities find it hard to say no to lucrative waste offers. "The targeting of waste companies for siting on Indian lands reflects the lack of options we have given the tribes," says Representative Duncan Hunter of California.

"Some tribes are prone to making decisions on an economic basis, because they have no choice," agrees George Bearpaw, executive director of tribal operations with the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. “They’ve got to provide employment and basic nieeds.”

A Flock of Buzzards

Despite the economic hardships, many Native Americans insist that they can survive better without waste dumps. Just as their ancestors resisted European invaders 500 years ago, Indians across the country are joining forces to defend their land against waste companies.

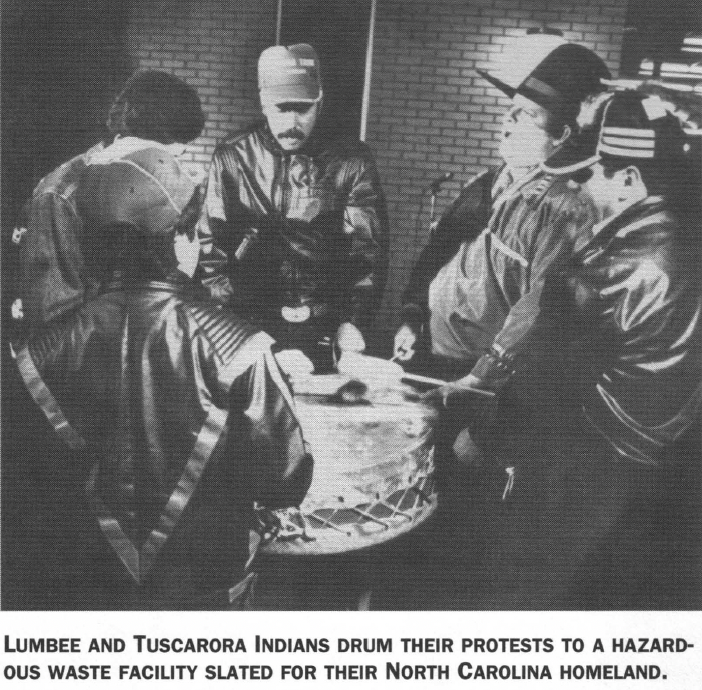

Lumbee Indians, who comprise 37 percent of the population of Robeson County in southeast North Carolina, have joined black and white residents to ward off two waste facilities since 1984. The first, an incinerator proposed by a company called U.S. Ecology, was defeated in two years. But after high-income, majority-white Mecklenberg Couty rejected a regional waste treatment facility proposed by GSX, the company and state officials spent eight years trying to locate the facility in the Lumbee homeland.

Under the proposal, GSX wanted to dump 500,000 gallons of waste into the Lumber River every day. "Some people are still subsistence living down at the river. It's a life source, rooted in Indian history," says Donna Chavis, a Lumbee resident. "We were looking at a major impact on our culture and way of living in terms of health risks."

To local residents, the waste plant was a clear example of environmental racism. "They don't see the racism that is buried in the efforts to site this facility," says Chavis. "They didn't have any idea that Robeson would be able to organize a campaign."

But organize they did. Recognizing that the county is 37 percent white and 26 percent African American, the Center for Community Action (CCA) in Lumberton emphasized crossracial organizing. The groups had different agendas, but the united effort produced huge turnouts at public hearings.

Finding resources was tougher. "Companies are bankrolling 10 to 20 professionals to locate a site, and most environmental campaigns cannot even hire one full-time staff person," says Mac Legerton, executive director of the CCA. “It's no wonder so many battles are still being lost."

Robeson citizens also found themselves up against federal regulators. After being lobbied by GSX, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency challenged a North Carolina law that provided more protection for drinking water than federal regulations. In what became a national test case, an EPA administrative hearing upheld the right of the state to maintain higher standards.

The community had won - but it wasn't long before the triracial community was once again forced to defend its land and cultures. ChemNuclear Systems, Inc. recently proposed siting a regional low-level radioactive waste facility in Richmond County, 30 miles from Lumberton. CCA is meeting with other local groups to strategize ways to stop the facility.

To further counter proposed waste facilities and strengthen the work of local activists, Native American groups have formed the Indigenous Environmental Network, a national coalition that provides education and technical assistance to more than 50 grassroots groups.

“Our goal is to help develop community empowerment,” says Jackie Warledo, who represents the IEN in the South. “When groups begin to face these issues, they will learn how to strengthen their own organizations.”

Some Southern groups are doing their own networking. North Carolina Cherokees, who recently fought off a 62-acre landfill, have united with Mississippi Choctaws in the Coalition for Native Rights. Despite the daily struggle of what Cherokee organizer Virginia Sexton calls “an all-day, every-day thing just to survive,” the two groups take time to share experiences and plan strategies. Together, their flyer says, they are finding ways to stop waste companies and government agencies from “circling over your sovereign nations like a flock of buzzards.

Death in the Tunnel

Unlike Native Americans, Africans brought to America in the early 17th century did not have their land taken from them; they were taken from their land. But like indigenous Southerners, they faced the brutal consequences of racism in their new environment, as white planters enslaved hundreds of thousands to power huge cotton and tobacco plantations.

As slaves, and later as freedmen, African Americans were consistently given the most toxic tasks. During the 1700s they were given dangerous jobs making tar, pitch, and turpentine in the coastal South. After the Civil War, they sorted tobacco leaves in rooms "laden with fumes and dust" for half the wages of whites and were relegated to the dirtiest, dustiest jobs in the new cotton mills. In the early 1900s, the federal government used black men in Alabama as guinea pigs in an experiment designed to test the long-term effects of syphilis. The men were never told what they had and were denied a cure when it became available.

In 1930, a subsidiary of Union Carbide hired nearly 5,000 workers - 3,244 of them black- to dig a four-mile tunnel at Gauley Bridge, West Virginia. Workers were told they were diverting water to supply a Union Carbide metal refinery with hydroelectric power. What they weren't told was that they were digging a tunnel through solid silica, which was known to scar the lungs and eventually suffocate those who inhaled its dust.

Some 2,000 black workers dug inside the tunnel, where the effects of the dust were the worst. Only 500 of the 1,687 whites worked inside. One observer said black workers were “treated worsen if they was mules.” When explosives were used, they were forced “right back into the powder smoke in the tunnel, instead of letting them wait 30 minutes like the white men do.”

James McGhee is the only black man still living who worked inside the tunnel. “We worked them rocks, they didn’t have anything on our noses,” he recalls. “They knew what was going to happen. We didn’t.”

Before long, at least 476 workers had died of pneumonia and were quickly buried in unmarked graves. “Many of them died in the tunnel,” says McGhee. “Ain’t no tombstone or nothing.”

Company officials were surprised. “I knew I was going to kill these niggers,” the contractor hired by Union Carbide later testified before Congress, “but I didn’t know it was going to be this soon.”

McGhee and more than 1,500 workers were disabled by silicosis. Whites who survived received as much as $1,000 in compensation; black workers received less than $250.

“I’m 86 now and I got silicosis and I can’t hardly breathe,” says McGhee. “They didn’t do anything for us.”

Highway Racism

As McGhee was watching hundreds of his fellow workers die in the hills of West Virginia, millions of black Southerners hoping to escape rural racism and find better-paying jobs were migrating to cities. In 1920, one in six blacks in Georgia lived in cities. By 1950, the ratio was one in three.

As African Americans created new urban communities, however, they encountered new forms of racism. When governments built highways, railroads, and other public works, they often routed them through black neighborhoods, uprooting decades-old communities from Dallas to Durham, from New Orleans to Nashville.

“The interstate highway departments have simply destroyed black neighborhoods by sending big interstates through there,” says John Hope Franklin, professor emeritus of history at Duke University. “I would call this an aspect of environmental racism.”

Once one public project disrupts a community, others quickly follow. The all-black neighborhood of Newtown in Gainesville, Georgia, separated from the white community by a parkway, is surrounded by dozens of dirty and dangerous industries. Over the years, residents have been plagued by pollution from an oil refinery, soybean mill, feed mill, wood treatment plant, auto factory, railroad terminal, landfill, and large junkyard. Of the 16 companies that report releases of toxic chemicals in the city, all but two are located in Newtown (see "No Answers for Newtown," page 52).

Residents say polluting companies endanger public health. "Out of 40 residents we surveyed, 18 people were sick or had died of cancer or lupus," says Faye Bush. "My sister had two kids who died with lupus. I had a brother who died with cancer. I had skin lupus. But the city and state didn't do a complete study. They blamed it on our lifestyles."

Determined to protect their families, Bush and her neighbors turned to the Newtown Florist Club, a civic group formed 40 years ago to collect money for flowers for ailing residents. Today the group is organizing to find out what chemicals are being released, educate the community, and push for cleanup.

Bush knows Newtown is not alone. "Everywhere you go," she says, "black people are crying the same story."

In fact, government studies show that black communities consistently suffer from the worst environmental conditions, including lead exposure, landfills, and toxic industries. A 1988 study by the Agency for Toxic Substances found that 44 percent of urban black children are at a risk of lead poisoning, four times the rate for white children.

Toxic Ghost Towns

While city life has been toxic to many African Americans, those who have tried to hold on to their farms have not been immune to environmental racism. In 1947, Mathew Grant moved his family into a resettlement community in Tillery, North Carolina. Such communities were established by the government to relocate people to rural areas when the demand for factory labor decreased after the Great Depression.

Like 350 other African-American farmers in the area, the Grants raised livestock and grew peanuts, com, cotton, and soybeans. When a few farmers sold off their plots during the 1950s and 1960s, others managed to buy the land and keep it within the community.

But federal programs run by the Farmers Home Administration favored white farmers. Black landowners had a hard time getting their loans refinanced and paid higher interest rates than their white counterparts. When the local FmHA tried to foreclose on 12 farmers in 1976, Grant and several others filed a complaint.

"There are clear practices of discrimination," says Grant's son Gary. "They did not offer black farmers the programs that were available, and the funding was always lower than was needed to survive. We're just talking about racism in all of its forms."

Corporate hog farms, timber companies, and other industries took advantage of the situation by buying up land, driving small farmers out of business, and polluting the drinking water. "Because we are a predominantly black community, the land value is already depressed,” says Gary Grant. "The land is much cheaper for purchasing by larger corporations."

Grant and other farmers formed Concerned Citizens of Tillery to fight back. They formed the Land Loss Fund to educate black farmers about protecting their land, and they have allied with the white community to fight the hog farms and hazardous waste incinerator. Last February, the NAACP and the Natural Resources Defense Council seda corporate hog Farm for placing a facility next to minority community and dumping hog waste into a nearby stream.

Across the South, streams and rivers and predominantly black communities like Tillery have proven particularly attractive to polluting companies. Over 700 chemical and industrial facilities line the banks of the Mississippi River, producing billions of pounds of toxic waste – and widespread illness among residence. Louisiana, which turns out a quarter of the nations chemicals, rank among the 10 states with the highest cancer rates.

Mary McCastle lives in a black community outside Baton Rouge that is surrounded by 15 chemical plants. "There used to be fresh air," she says. "It was just acres of land you could sit in the yard, and now you can't. Some people have died from this. You could be woke up at night and strangled by the smoke.”

McCastle, president of the Coalition for Community Action, says polluting companies, take advantage of rural poor communities of color. "They come in as a good neighbor, but we found out they was a bad neighbor. They put it in predominantly black areas where people don't have the money to move."

In some areas, the health effects of decades of pollution have been so severe that companies and government agencies have found it cheaper to pay entire communities to move rather than clean up the mess. In Louisiana, companies have "bought out " Sunrise, Good Hope, Reveilletown, and other communities, creating toxic ghost towns.

Patsy Oliver lived a predominantly black subdivision of Texarkana, Texas for 25 years before she was bought out earlier this year by the Army Corps of Engineers. The neighborhood, it turned out, had been built on a chemical dump containing creosote and arsenic, and residents were sick with cancer, rashes, and respiratory elements. Oliver had a gallstone rupture and her husband had kidney problems and thyroid surgery.

Oliver blames federal regulators for failing to act sooner. "More people could've been spared if they hadn't drug their feet. It was really environmental racism and genocide."

Destruction of entire communities, many African Americans are looking for grassroots alternatives to toxic industries and corporate development. On Sapelo Island in Georgia, where mass oyster harvesting and hotel and restaurant projects threat and black and Indian farmers and fishers, the McSap Development Corporation is trying to give local people jobs and sustain their land.

"The issues of black owned land and reparations cannot be dealt with in isolation from issues of ecological and social justice," says Sulaiman Mahdi, who worked with McSap as Southeast regional director of the Center for Environment, Commerce and Energy in Atlanta. "How we treat the land is reflected, and how we treat the people who live on it."

Chemical-Laden Crops

African slaves were the first people of color brought to the South to work the land, but they were not the last. After the Civil War, white farmers turned to migrants from other countries to work the fields for low wages and often hazardous conditions.

Beginning in the 1860s, Chinese workers came from the West Indies, and later directly from China, to work on Louisiana and Mississippi plantations. But high unemployment among whites fueled resentment against foreign workers, and Congress ordered a halt to Chinese immigration in 1882.

Then, in 1910, the downfall of Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz prompted a massive immigration of Mexicans to the United States. Over the years, workers from the Caribbean, Central America and Pacific Islands followed.

In the South, most of the migrant labor centered in Texas in Florida, where conditions for Latino and black farmworkers were brutal. Adults and children did backbreaking field work harvesting chemical-laden crops for long hours and low wages.

When Cora Tucker was growing up during the 1940s, her family worked in the tobacco fields of Virginia. The arsenic powder farmers put on tobacco to keep worms off, she recalls, would “make strange things happen.” Five-year-old girls menstruated. Boys got nosebleeds.

It was not until 1962 that three events finally brought the hazards of pesticides into the public spotlight. The book Silent Spring documented, the harmful effects of DDT, prompting a public outcry. The Migrant Health Act, passed the same year, provided some money for clinics, although it did not reach most workers. And Cesar Chavez founded the National Farm Workers Association, later known as the UFW, to improve conditions for farmworkers.

Public concern eventually waned when DDT was replaced with organophosphates, which pose less threat to consumers. But farmworkers cannot escape the acute toxic effects of the newer pesticides, which can inflame the skin and eyes, infect the lungs, and cause cancer, birth defects, chronic fatigue and headaches, and liver and kidney disorders. One study found that as many as 313,000 farmworkers suffer from pesticide-related illnesses each year. The life expectancy of migrant workers is 49 years – more than 20 years below the national average.

Most of those threatened by pesticides are people of color. Evonne Charboneau with the Farmworker Health and Safety Project of Texas Rural Legal Aid first started working with farmworkers in 1983. "Cropduster sprayed human beings with poisons, not even stopping to warn people to get out of the field," she recalls. "Upper middle-class white people wouldn't be treated that way."

Tirso Moreno picked oranges in Florida groves for 13 years before becoming an organizer with the Farmworkers Association of Central Florida. He says conditions have not improved much over the years. "Because we are people of color, we have never had enough control. Because we are farmworkers we have been put at the bottom of everything."

The only way to adequately protect farmworkers, advocate say, is to stop using pesticides. "Growers are losing more to pests now than they were before they were using the pesticides," says Rebecca Flores Harrington, state coordinator for United Farmworkers in Austin, Texas. "In the process they’re poisoning everything else in the environment."

To educate the public and end the use of pesticides, the UFW produced a documentary called The Wrath of Grapes, a visual account of the danger of agricultural chemicals. The union also launched a national boycott of grapes, which are sprayed with dozens of different pesticides that affect 55,000 workers.

Farmers and other Hispanic Americans in barrios from Texas westward also found a friend in the SouthWest Organizing Project. In the early 1980s, SWOP cofounder Richard Moore and five other activists surveyed communities across the region. They found that while community-based organizations were disappearing, national groups were stepping in and determining local agendas. SWOP helped empower local organizers to pursue local strategies.

Before long, organizers realized that pesticides, sewage and lead poisoning – long considered issues of poverty – were also environmental. Communities began to make the connection between the poor condition of their environments and the fact that they were poor people of color. "It was very intentional that neighborhoods were being targeted" for pollution, says Moore.

In 1990, SWOP organized a regional three-day meeting that brought together local activists, workers, church leaders, and Mexicans from south of the border to share their stories. The participants discovered that they could protect their communities better by exchanging information about polluting industries. "If we had mechanisms where we could share that information with each other, we could save some lives," says Moore. The result was a new regional coalition, the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice, dedicated to sharing information and pushing for cleanup and better, environmental regulations.

Fighting Back

Such grassroots organizing and coalition building among migrant workers, black residents, and Native Americans lies at the heart of the emerging movement for environmental justice. Indeed, what brought the centuries-old pattern of environmental racism to national attention was a local struggle over how to manage deadly waste in a rural, black-majority community in North Carolina.

In 1978, the state was looking for a place to store 40,000 cubic yards of roadside soil that had been illegally sprayed with carcinogenic PCBs. Backed by the EPA, state officials decided to dump the deadly waste in Warren County. Although the county failed to meet federal geological standards, it had something more important: a population that was overwhelmingly poor and 64 percent African American.

"They put a dump in a county that had no way economically or politically to defend itself," says Dollie Burwell, a Warren County resident. "While it was an environmental issue, it was more of a justice issue. That's why for me it was the beginning of the environmental justice movement."

The county waged a protest that caught the state - and the rest of the nation - by surprise. Local citizens protested the dump by attending hearings, staging letter-writing campaigns, and lying in front of the PCB-laden trucks when they began bringing in the dirt in 1982. More than 500 protesters were arrested, making headlines in Newsweek and airtime on the CBS Evening News.

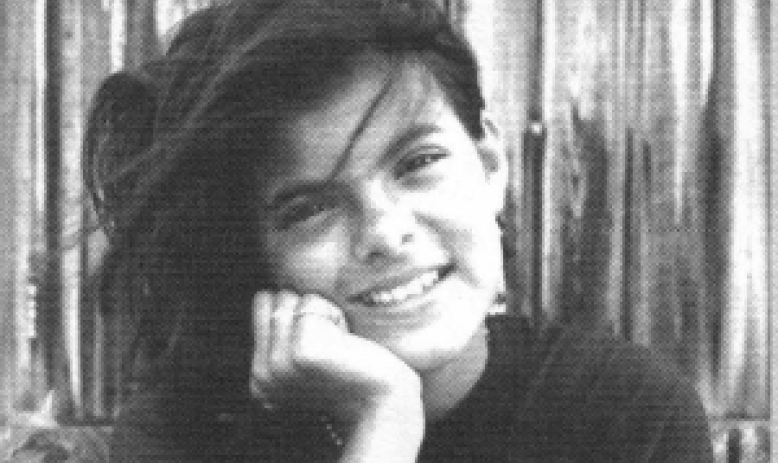

Burwell and her neighbors enlisted the help of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta and Ben Chavis at the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice. Her 10- year-old daughter Kim looked into the cameras and told the nation, "I'm not afraid of going to jail-I'm afraid of this poison that is coming to my county."

Although continued protests and a series of legal challenges failed to keep the dump out of Warren County, they spurred black residents to become more involved in local politics, registering to vote and electing more black officials. Dollie Burwell became county registrar of deeds.

The fight also prompted the Commission for Racial Justice of the United Church of Christ to investigate the connection between race and toxics. In a landmark statistical study published in 1987, researchers found that race, even more than class, determines where polluting industries and dumps are located. In his 1990 book Dumping in Dixie, Robert Bullard of the University of California also documented how waste companies target politically powerless black communities, particularly in the South - and noted the strong activism against such sitings by people of color.

Recent studies and investigations have confirmed that people of color bear a disproportionate share of the waste burden:

- The Institute for Southern Studies reported in its Green Index that four of the states with the largest share of African American or Hispanic populations in the nation - Texas, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi - also rank among those with the most pollution, poorest health, and worst environmental policies.

- An EPA study concluded that low-income people and racial minorities "appear to have greater than average observed and potential exposure to certain pollutants because of historical patterns affecting where they live and work."

- In five of eight studies reviewed by University of Michigan researchers Paul Mohai and Bunyan Bryant, race was a more significant factor than income in determining which communities were the most polluted.

- An award-winning investigation in the National Law Journal documented racial discrimination in the enforcement of environmental laws. The study found that white communities "see faster action, better results and stiffer penalties than communities where blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities live." The study found that it takes the government 20 percent longer to place minority communities on the Superfund list for cleanup and imposes weaker penalties on polluters and minority communities.

The Big Ten

Such reports underscore the importance of environmental justice struggles by people of color – and the failure of major environmental organizations to support such efforts. In 1988, only six minorities sat on the boards of the 11 largest national environmental groups, including the National Wildlife Federation, Audubon Society, Sierra Club, and Environmental Defense Fund. in addition, fewer than two percent of the professionals on staff were people of color.

The big environmental groups also control the big money. A review conducted by Southern Exposure of all foundation grants given to 3,332 environmental organizations in 1991 revealed that a handful of mainstream groups known as the "Big Ten" received $20.4 million - six percent of all grant money.

Angered by the racial and funding inequities, both the Louisiana-based Gulf Coast Tenant Organization and the South West Organizing Project sent letters to the "Big Ten" in 1990, demanding that they diversify their staffs and boards and focus more attention on the plight of polluted communities where people of color live and work. "We care about the outdoors and wildlife, but we care about ourselves and our families, too," explained SWOP co-founder Richard Moore. "These groups weren't taking positions against the poisoning of our communities."

Grassroots organizers were disappointed by the lack of response. "The big groups still had a fear of sharing power," says Moore. "They missed a major opportunity. If we had some dialogue and came to some agreements, it could make an incredible difference in saving the lives of many people."

Frustrated by the lack of representation among mainstream environmental groups, grassroots leaders looked for ways to forge a larger movement - one led by people of color and responsive to local struggles. The result was the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, convened by the UCC Commission for Racial Justice in October 1991.

Over 600 delegates and white observers gathered for three days of plenary meetings, workshops, panel discussions, and time to share stories in hallways and over meals. In a collaborative and sometimes difficult series of working sessions, a committee of delegates hammered out 17 principles of environmental justice that have become a defining document for the movement (see "The Principles," page 19).

The summit also allowed participants to share frustrations about the Environmental Protection Agency. "EPA is here to protect us, but they do everything but protect us," said Patsy Oliver of Texarkana.

Turning their frustration into action, the Southwest Network, researchers, and organizers wrote to the EPA, calling for accountability to communities of color. As a result of their demands, the agency set up a workgroup to study environmental equity.

In its final report, the EPA workgroup concluded that "there are clear differences between racial groups in terms of disease and death rates." It added, however, that "there are also limited data to explain the differences." The only clearcut evidence of a link between race and environmental risk, according to the group, is the high rate of lead poisoning among blacks.

"Is there systematic racism out there?" said Robert Wolcott, chair of the group. "I don't think so. It's more economic class."

Grassroots leaders were furious that the study group had ignored widespread evidence of environmental racism, and asked why the agency did not fund new studies if it felt there was a lack of data. "It's definitely racial discrimination," said Benjamin Chavis, director of the NAACP. "I'm not saying whites are not exposed. I'm saying the disproportionate exposure to minorities has been the result of systematic policy-making."

Frustrations with the EPA peaked last year when Congressman Henry Waxman released a confidential agency memo. The internal EPA document lays out a coordinated public relations plan to deflect grassroots political pressure and woo civil rights groups away from the environmental equity issue.

According to the memo, the agency should try to draw support away from civil rights groups before the "minority fairness issue" reaches a point where "activist groups finally succeed in persuading the more influential mainstream groups (civil rights organizations, unions, churches) to take ill-advised actions."

Waxman says the memo demonstrates that the EPA "views the environmental equity initiative as a public relations matter, not an opportunity to understand and respond to the very real health problems faced by people of color. The agency is concerned about appearances, not substance."

Among the strategies listed in the memo was holding meetings at historic black colleges to discuss the agency's equity plans. But when the first meeting was held at Clark Atlanta University in September 1992, the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC) was ready. The 150 citizens who attended ordered industry representatives to leave, outlined 42 demands for more environmental enforcement and citizen participation, and listed "hot spots" across the South that needed immediate EPA attention.

"We kicked out the industries," says Connie Tucker, Atlanta coordinator for SOC. "It shows the frustration of our people - white and black - that they were ready to come together to do something."

EPA officials say the Clinton administration is committed to involving community leaders in decision-making and increasing the flow of money to polluted communities. Warren Banks, a special assistant to EPA head Carol Browner, says the agency is already cleaning up "hot spots" in places like Columbia, Mississippi where it has moved slowly in the past.

"I feel that we are moving very fast," says Banks. "But of course, we were way behind."

Beyond the Summit

Leaders of the environmental justice movement are used to such government promises- and they aren't waiting for federal regulators to take action. Last December, 2,500 activists converged on New Orleans for a regional meeting sponsored by SOC.

"They came to New Orleans because they're losing their lives and their families are dying," says Damu Smith, who helped organize the conference. "We helped stimulate more of a coordinated effort among groups that already existed." To share information and strengthen the movement, some activists agreed to start state networks. A Mississippi network that got under way in August has already become a model for other states.

Among the New Orleans participants were several hundred young activists, mainly junior high and high school students, who had ridden freedom buses to the meeting. "We've never had a movement where youth were not the foot soldiers," says Angela Brown, Youth Task Force coordinator for SOC. "Youth are always forcing the tight-fisted establishments to change policies and procedures."

While young people have the freedom and energy to support a struggle, they lack resources to travel and communicate. "Foundations are not willing to fund young people. We barely have a fax or computer," says Brown. Despite such limitations, the task force has established several state offices and a speakers bureau, and recently held a planning meeting that included a panel of elders experienced in building justice movements.

More mainstream student groups are also starting to make environmental justice a priority. The Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC) originally formed to organize college students around forestry issues and now has members in over 2,000 high school and college groups in all 50 states. Moving from white leaders and issues to a more diverse agenda and membership hasn't come easy, organizer say, but after much discussion the group devoted its 1991 annual conference to the issue of social and environmental justice.

Two years later, half the members of SEAC’s national council are people of color, and students at the national headquarters in Chapel Hill, North Carolina have supported the black housekeeping staff in their demands for better pay and working conditions.

"I have had an easier time working with SEAC than other groups," says Kristi Shastri of the group’s People of Color Caucus. "Our national structure has incorporated an integrated understanding of global environmental justice issues."

Such efforts among young young activists will help carry the environmental justice movement into the next century. "We are struggling with a question of how we move forward from here," says Angela Brown of SOC. "It's not a question of whether— it's a question of how. We are just a quiet storm that’s starting to brew."

The Principles

In 1991, delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit drafted and adopted 17 Principles of Environmental Justice. Since then, the principles have served as a defining document for the growing grassroots movement for environmental justice.

WE THE PEOPLE OF COLOR, gathered together at this multinational People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, to begin to build a national and international movement of all peoples of color to fight the destruction and taking of our lands and communities, do hereby re-establish our spiritual interdependence fro the sacredness of our Mother Earth; to respect and celebrate each of our cultures, languages and beliefs about the natural world and our roles in healing ourselves; to insure environmental justice; to promote economic alternatives which would contribute to the development of environmentally safe livelihoods; and, to secure our political, economic, and cultural liberation that has been denied for over 500 years of colonization and oppression, resulting in the poisoning of our communities and land and the genocide of our peoples, do affirm and adopt these Principles of Environmental Justice:

1. Environmental justice affirms the sacredness of Mother Earth, ecological unity and the interdependence of all species, and the right to be free from ecological destruction.

2. Environmental justice demands that public policy be based on mutual respect and justice for all peoples, free from any form of discrimination or bias.

3. Environmental justice mandates the right to ethical, balanced and responsible uses of land and renewable resources in the interest of a sustainable planet for humans and other living beings.

4. Environmental justice calls for universal protection from nuclear testing and the extraction, production and disposal of toxic/hazardous wastes and poisons that threaten the fundamental right to clean air, land, water, and food.

5. Environmental justice affirms the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural and environmental self-determination of all peoples.

6. Environmental justice demands the cessation of the production of all toxins, hazardous wastes, and radioactive materials, and that all past and current producers be held strictly accountable to the people for detoxification and the containment at the point of production.

7. Environmental justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation.

8. Environmental justice affirms the right of all workers to a safe and healthy work environment, without being forced to choose between an unsafe livelihood and unemployment. It also affirms the right of those who work at home to be free from environmental hazards.

9. Environmental justice protects the right of victims of environmental injustice to receive full compensation and reparations for damages as well as quality health care.

10. Environmental justice considers governmental acts of environmental injustice a violation of international law, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and the United Nations Convention on Genocide.

11. Environmental justice must recognize a special legal and natural relationship of the Native Peoples to the U.S. government through treaties, agreements, compacts, and covenants affirming sovereignty and self-determination.

12. Environmental justice affirms the need for urban and rural ecological policies to clean up and rebuild our cities and rural areas in balance with nature, honoring the cultural integrity of all our communities, and providing fair access for all to the full range of resources.

13. Environmental justice calls for the strict enforcement of principles of informed consent, and a halt to the testing of experimental reproductive and medical procedures and vaccinations on people of color.

14. Environmental justice opposes the destructive operations of multi-national corporations.

15. Environmental justice opposes military occupation, repression, and exploitation of lands, people and cultures, and other life forms.

16 Environmental justice calls for the education of present and future generations which emphasize social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives.

17. Environmental justice requires that we, as individuals, make personal and consumer choices to consume as little of Mother Earth’s resources and to produce as little waste as possible; and make the conscious decision to challenge and reprioritize our lifestyles to insure the health of the natural world for present and future generations.

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)

Charles Lee

Charles Lee is research director with the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice in New York. (1993)