The Emelle Megadump

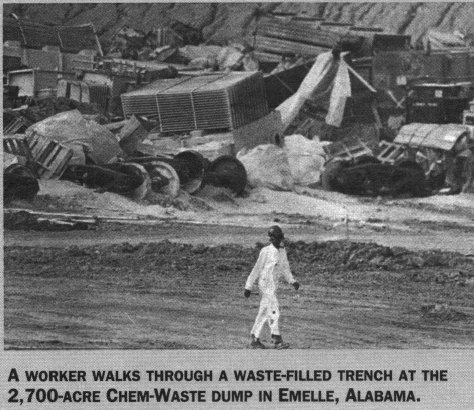

Emelle, Ala.— The largest toxic waste stump in the nation sprawl across 2,700 acres of Sumter County, its trenches as much as a half mile long and 600 feet wide. Trucks hauling hazardous waste from 48 states and foreign countries pass through its skates 24 hours a day.

According to the Census Bureau, approximately 16,000 people live in the rolling hills of West Central Alabama that surround the waste up. More than 11,000 residents are African-American. Unemployment is 14 percent. Annual income averages barely $10,000.

The proximity of waste and race is no coincidence. As cities have looked for low-cost alternatives to traditional landfills, privately owned “megadumps" like Emelle have become increasingly attractive. The trouble is, commercial dumps require a guaranteed tonnage from outside the county and state to turn a profit, and the trucked-in waste winds up covering hundreds or thousands of acres. To keep land cheap and avoid political opposition, waste companies have made poor, rural counties with high populations of people of color the dumping ground for the nation.

The Emelle dump got its start in 1977, when the son-in-law of then-governor George Wallace and three Tennessee partners opened a waste landfill of 340 acres of farmland in north Sumter. A year later, they sold the site to the Illinois firm of Waste Management, Inc. The company – now known as WMX – bought up surrounding land and turned the dump over to its subsidiary, Chemical Waste Management.

"It's a classic case of environmental racism," says Wendell Paris, who lives 5 miles from the dump. "The community was taken completely by surprise."

There were no public hearings, and most citizens believed the giant facility would be a limestone quarry or brick foundry. In any case, the impoverished county needed jobs, and community leaders considered the potential environmental risk less important than regular paychecks and food on the table.

Before long, however, resident discovered that jobs at the dump or scarce and health risks were plentiful. The landfill contains 1 millions of tons of deadly waste, including illegally dumped radioactive waste and half of the land disposable PCBs produced in the eastern part of the country.

Spills, explosions, fires, and evacuations have played the dump. Truckers cited for drunk driving has spilled poisonous phenol and nitrobenzene that they were transporting to Emelle. In 1989, state troopers found 740 violations and 312 trucks shipping waste to Emelle and took 51 vehicles out of service.

Since the dump opened for business, many residents and industries have fled the county, driving down already low property values. The landfill has become the largest employer, increasing its tight grip on the local economy.

In 1991, public concern peaked when a water well was drilled near the dump to provide drinking water for over 1,000 residents. Alarmed by possible contamination, citizens and political leaders called for the well to be capped. But the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the local water authority ignored community opposition, and the well was approved for public use.

When one nearby community refused to be connected to the well, the Alabama National Guard had to be called in to provide residents with water for two weeks. The county water authority voted unanimously to honor the community’s rights and press for an alternative water source, but state officials are demanding that the community be connected to the controversial well or face stiff penalties.

Organizing can be difficult in a poor, racially divided part of the Deep South, where people are dependent on the waste dump for employment, and where protesters have lost jobs and faced death threats. Nevertheless, residents formed the West Alabama East Mississippi Community Action Network—“We Can”—to fight the dump and improve their quality of life. The group works to make local officials accountable to the people they serve, and hopes to develop the economy by finding alternative uses for the chalk that is such an abundant component of the local terrain.

“Based on our experience in Emelle, we have to alert other unsuspecting communities as to what will actually happen if they locate a hazardous waste site,” says Wendell Paris. “The first thing we have to do is educate. Once folks have the correct information, most of the time they will make the correct decision.”

Kaye Kiker chairs the board of the Sumter County Water Authority and is a member of the West Alabama East Mississippi Community Action Network. Cleo Askew is a board member of the Water Authority and works on housing and environmental issues with the Federation of Southern Cooperatives.