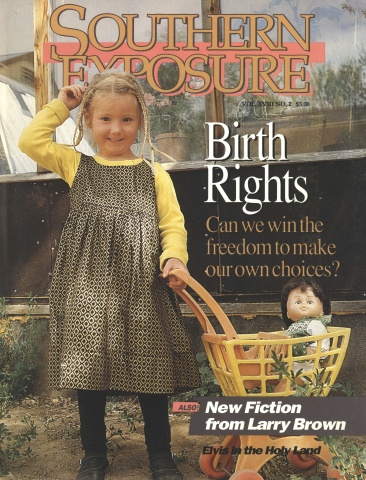

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

Washington, D.C. —Lillie Ruth Watson stood before the microphone, speaking to reporters from the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, television networks, and dozens of newspapers from across the country. She showed them the surgical scars on her wrists and hands, and she described how cutting up millions of chickens on a brutally fast production line had crippled her. She said her hands still hurt too much to clap at church revivals or comb her granddaughter’s hair.

Watson was permanently injured while working for Frank Perdue, the wealthy poultry producer best known for his televised boast that “it takes a tough man to make a tender chicken.” Perdue was certainly tough with Watson. When she got hurt after 13 years on the job, she said, the company “treated me just like a worn-out pair of shoes.”

“I kept going to the nurse complaining about my hands,” Watson said. “She give me liniment and sent me back to work on the line. My hands got worse.” After each of her three operations, she faithfully returned to the plant but was refused light duty. “I couldn’t stop work. I had five kids to support.”

When she finally took her complaint to the personnel manager, he told her, “I can’t stop your hands from hurting. You just don’t want to work.”

Recounting this story at the July press conference last year marked a dramatic turning point for Watson. Only two months before, when interviewed for a Southern Exposure special report entitled “Ruling the Roost,” she had asked that her name be changed to protect her from reprisals. Now, she was speaking out on national television, telling a story that has become painfully familiar to thousands of poultry workers.

A year later, little has changed in the way poultry companies go about their business. Farmers under contract to the big processors are still being driven deep into debt. Workers who gut and cut chickens still describe their work as “modem slavery.” And consumers who eat poultry are still being exposed to millions of sick birds every day.

But thanks to people like Lillie Ruth Watson cracks are starting to appear in the system.

In small yet significant numbers, farmers and workers are fighting back — and they are beginning to score some major victories. In the past year, state and federal agencies have levied unprecedented fines against poultry firms. Courts have penalized companies for treating farmers unfairly. And policymakers are considering rules that would force processors to slow down production lines and safeguard workers who report health hazards.

“We measure success one person at a time,” said Sarah Fields-Davis, director of the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives (CWEA), which helped Watson gain self-confidence, seek workers compensation, and become an advocate for industry-wide reforms.

“The national attention has helped,” Fields-Davis continued. “We see the change in the attitude of people inside the plants, in how people feel about themselves and what they’re willing to do. They know someone cares. They know Perdue is being watched.”

“The Gig is Up”

The horror of the modem poultry industry came into national focus last summer when the Institute for Southern Studies, the research and education center that publishes Southern Exposure, released “Ruling the Roost” at a press conference at the National Press Club.

That’s where Lillie Watson told her story. David Mayer, an unassuming chicken fanner from North Carolina, also overcame his fear of public speaking to report how heavily mortgaged farmers are trapped into one-sided contracts that pay less than minimum wage. And microbiologist Gerald Kuester revealed that chicken on grocery-store shelves is now contaminated at twice the rate certified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The press conference resulted in a flurry of media coverage, and the feathers have been flying ever since. Meat and Poultry, the leading industry trade journal, groused that the “thoroughly researched and documented” report in Southern Exposure was influencing public opinion. “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” wrote the editor, who advised poultry companies to counter the bad news by inviting local TV reporters into their plants.

After unsuccessfully fending off the media, Perdue Farms took the advice and permitted a crew from the ABC program 20/20 into its slaughterhouse in Lewiston, North Carolina. Working closely with CWEA and the Institute, the 20/20 staff gave millions of consumers a firsthand look at the high-speed processing line on which hundreds of black women risk permanent injury gutting, cutting, trimming, and deboning more than 30,000 chickens a day.

“When people hurt their hands and arms they take them off the line for a brief period, then put them right back,” said Grace Valentine, a former Perdue worker interviewed on the show. Her words were echoed by a group of workers interviewed in the company lunch room — even though Perdue officials hovered just behind the ABC cameras.

For exposing the travesty of the modem poultry jungle, Southern Exposure earned the 1990 National Magazine Award for public interest reporting in April. In presenting the award, the judges called the pioneering report “the very human story of an industry that feeds millions of Americans every week and reportedly makes far too many of its customers and workers sick.” Two weeks later, Watson won a major victory of her own when the Social Security Administration awarded her total disability benefits. The unusual ruling acknowledges that Watson has been permanently disabled by her work. “My hands still hurt—they hurt whether I use them or not,” Watson said. “There’s no other kind of work I can do, what with my education, without using my hands.”

The decision signals a growing awareness of the dangers of repetitive motion injuries. “It’s becoming more and more apparent that these injuries affect a person’s life more than we previously thought,” said Steve Edelstein, an attorney for Watson and other disabled Perdue workers. “They can literally make a person unemployable.”

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recently released new workplace safety guidelines for the red-meat industry, and Edelstein predicted the new procedures would become a model for repetitive tasks in chicken processing. “Industry knows the gig is up,” said Edelstein. “Instead of denying these injuries are work related, they’re now disputing the degree of a person’s disability. That’s why the decision in Lillie’s case is so significant.”

91 Birds a Minute

Poultry companies have also been put on the defensive by a wave of OSHA fines. Since “Ruling the Roost” was published, state and federal officials have cited five chicken processing plants for violating OSHA’s “general duty clause” that requires workplaces to be free of serious health hazards. In October, the North Carolina Department of Labor fined two Perdue plants $40,000 for hazardous conditions that cause repetitive injuries and for not reporting the injuries on OSHA logs. It was the largest OSHA fine ever handed down in the state—and the first ever for repetitive motion trauma.

To protect workers, OSHA recommended that Perdue slow down the processing line, provide sharpened cutting tools, install machinery that minimizes stress, and rotate workers who perform highly repetitive tasks.

Two weeks later—in response to months of pressure from the Retail, Wholesale & Department Store Union — federal OSHA fined a Cargill plant in Georgia $242,000 for 113 violations, charging that the poultry company “knowingly and willfully” kept workers in repetitive motion jobs that caused hand and wrist disorders. In November, OSHA also fined two Missouri turkey plants owned by Cargill and ConAgra a total of $1.75 million.

Perdue appealed the North Carolina OSHA fine, arguing that as long as no specific standard exists for line speeds, it doesn’t have to change its production process. State officials fear they will lose, but a group of Perdue workers organized by CWEA are now official parties in the case and are fighting the appeal. Attorneys from the Occupational Safety & Health Law Center in Washington pressed for an immediate line slowdown during the appeal, but Perdue has fought such “interim relief.”

In May the company took matters a step further by trying to block the release of an in-depth investigation by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). The federal study of conditions in the two plants confirms accounts by workers and directly contradicts Perdue’s claims that less than one percent of its workers suffer from cumulative trauma disorders (CTD).

According to the report:

36 percent of Perdue workers in jobs requiring repetitive motions have symptoms of CTD, and one in five suffers serious CTD problems.

99.5 percent of the workers in those high-risk jobs are black, while whites hold half the non-repetitive jobs.

Nearly a quarter of workers with CTD symptoms in one plant were not allowed to leave their work stations to see the company nurse. Two-thirds reported that they were forced to work with dull scissors or knives.

When the report’s principal author attempted to present his findings at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Perdue lawyers argued that the report could not be made public while the company appeals the OSHA fine. Both the North Carolina attorney general and the state Department of Labor—which is responsible for protecting workers — sided with Perdue.

NIOSH rejected the censorship effort, but the judge hearing Perdue’s OSHA appeal ruled that the company could maintain its current line speed of 91 birds a minute throughout the appeals process — which could extend into 1991.

Workers and their advocates were angered by the decision. “I’m hopeful that OSHA won’t back off and will actually do something,” said Sarah Fields-Davis of CWEA. “But we can’t really claim victory until they reduce the line speed. That’s the one thing that would cut down on CTD injuries.”

Although more poultry workers are speaking out, their fear of losing their jobs remains high. Less than one-fourth of poultry workers are covered by labor contracts, and union locals must fight hard for every gain they achieve. Last fall 530 poultry workers in Macon, Georgia won a four-week strike against Cagle Inc., securing their first pension, a wage increase, better sick leave, and a company promise to have medical personnel on hand during each shift.

Whose Chicken?

Like slaughterhouse workers, farmers who grow chickens on contract fear losing their livelihoods if they confront poultry companies. Since the publication of “Ruling the Roost,” poultry farmers from nine states have called the Institute for Southern Studies to express their frustration with the contract system.

“In my opinion the poultry grower is presently the most oppressed agricultural worker since the times of slavery,” wrote one farmer. “The poultry companies strive to keep growers mortgaged, isolated, and uninformed.”

He closed his letter with “sorry, but I can’t sign my name yet.”

Nearly all chicken farmers today contract directly with a poultry processing company, which supplies the birds, the feed, and rigid requirements on the design and equipment of chicken houses. Thousands of Southern farmers, enticed by promises of lucrative pay, have mortgaged their homes and land to build $100,000 chicken houses. But most have found themselves plunged deeper into debt, as companies require them to upgrade equipment or lose their contract.

Mary Clouse and her husband raised breeder hens for 12 years. Last summer she decided to speak out. “You are like a serf on your own land,” she told Southern Exposure in a line that was picked up by many newspapers.

Shortly after the interview appeared, the Clouses received a call informing them that their hens would be picked up in three days and no new ones would be delivered.

“I feel it was because of the article, but it would be difficult to prove it in court,” said Clouse. “The contract system is skewed against the farmer. There’s no guarantee beyond the next flock of birds — and for a broiler grower that’s only seven weeks.”

“After you’ve invested hundreds of thousands of dollars you can’t take it or leave it,” she added. “You have to take it because you have to meet your mortgage payments on those chicken houses.”

Working with the Institute and the United Farmers Organization, Clouse and other poultry farmers have started a newsletter to keep growers abreast of organizing battles. “The main thing poultry growers need right now is a means to communicate,” Clouse said. “Most farmers don’t realize that they are not the only ones suffering these indignities.”

Through the newsletter, farmers are learning for the first time that growers in several states have won major legal victories that challenge the industry’s power to unilaterally define contract terms.

In southern Alabama, 268 growers recently won the largest cash award in history against a poultry company — $13.5 million. The jury found ConAgra guilty of fraud and breach of contract for short-changing farmers by routinely misweighing truckloads of birds. ConAgra is appealing the case, but the evidence is overwhelming.

A few weeks later, ConAgra paid a large out-of-court settlement to 18 farmers in northwest Louisiana who had charged the company with arbitrarily cutting off their flocks. The growers contended that the company bound them to “contracts of adhesion,” which gave them no rights and amounted to involuntary servitude. Rather than let such a fundamental issue go before a jury, ConAgra settled the case in exchange for a promise that the growers would keep quiet about the deal.

In the year’s most significant case, a federal judge in Florida ruled that growers who organize and complain about their contracts are protected from company retaliation. The case began when 38 growers sued Cargill for systematically under weighing their birds. The company responded by terminating its contract with Arthur Gaskins, the lead plaintiff and president of the Northeast Florida Broilers Association.

Gaskins, who has raised chickens for 21 years, decided to fight back. He sued Cargill for unlawful retaliation, got the U.S. Justice Department to enter the case on his side, and in April won a temporary restraining order that forced Cargill to put birds back on his farm. The federal judge said Gaskins — and all other Cargill growers—are protected from retaliation under the Packers & Stockyards Act, Agricultural Fair Labor Practices Act of 1967 and state and federal anti-racketeering statutes.

“Cargill’s position, much like that of other poultry processors, was that the contract could be terminated ‘at will* — for any reason, or for no reason at all,” said Jim Grippando, the attorney who represented Gaskins. “This decision is good news for all poultry farmers because it interprets federal statutes to mean processors are prohibited from treating growers unfairly.” Grippando’s law firm, one of Florida’s largest and most politically active, took the case a step further. At their urging, the chair of the state senate agriculture committee proposed a bill that would make it a state crime for poultry companies to terminate farmers without just cause and due notice. The unprecedented legislation drew such vigorous protest from the poultry and egg industry that the sponsor withdrew the bill, settling for a state investigation of contract abuses. The investigation could provide the basis for reintroducing the law next year, and provide a model for other states to follow.

Toxic Technology

As farmers and workers push for better working conditions, safe food advocates have been fighting to protect consumers from contaminated chicken. The USDA admits that up to 37 percent of all chickens approved by government inspectors are tainted by salmonella, a deadly bacteria which poisons an estimated four million Americans each year and kills thousands.

Instead of beefing up its inspections, USDA actually cut back the number of slaughterhouse inspectors during the 1980s and adopted a “Streamlined Inspection System” that rejects fewer sick birds. At one plant using the new system, a USDA study showed that more than three-quarters of the birds leaving the facility were contaminated with salmonella.

The Government Accountability Project (GAP) in Washington has collected 130 affidavits from inspectors blowing the whistle on lax regulation. One inspector complained that he is only permitted to condemn 40 percent of the chickens he condemned 10 years ago.

This year, Congress responded to the growing public outrage by authorizing an additional 320 inspectors, but consumer advocates say more inspectors may not be enough.

“It would be premature to say that more inspectors on the line would solve the problem,” said Tom Devine, legal director of GAP. It’s a step in the right direction, he noted, but“ inspectors complain that the fast line speeds and the loss of authority they’ve experienced in recent years have tied their hands and reduced them to the role of window dressing.”

As GAP and safe food proponents focus on changing the fast-paced production systems that spread filth among birds, the Food and Drug Administration took a different approach in May. The federal agency announced that poultry could safely be treated with three times the levels of radiation allowed for other foods in order to kill salmonella and other troublesome bacteria. Consumer advocates and scientists immediately criticized the FDA action. “Treating toxic chicken with a toxic technology is not the way to improve the safety of poultry,” said Michael Colby, director of Food & Water, a consumer research group in New York.

Studies of food irradiation have shown that the process creates cancer-causing byproducts, exposes workers and communities to serious hazards, and kills organisms that produce the bad odor and color which warn consumers their meat is rotting. So far, no poultry company has said it will irradiate its chickens, but Food & Water is organizing opposition to a proposed processing plant in central Florida which would house an irradiation facility.

“The irradiation proposal illustrates how the poultry industry embodies what’s in store for us in matters related to food, the farm, or the factory,” said Bob Hall, the Institute’s research director. “Other industries are making proposals — from synthetic additives to biotech engineering — that would mask unsafe food rather than treat the problem at its source. They want to use untested technological fixes to overcome deficiencies that naturally arise because of bad processing or growing methods.”

In farming, he added, “the contract system is moving so quickly into hogs and cattle that people are talking about * the chickenization of beef and pork.’ And repetitive trauma—already the nation’ s fastest growing occupational illness— promises to escalate in the coming years, especially in workplaces with unorganized, often isolated workers.

“All that means the struggle in poultry is both very specific and very broad,” Hall said. “There are people in pain, and at risk, right now — and there are also big consequences for the struggles of other consumers, farmers, workers, for all of us. It’s a helluva fight.”