This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 2, "Birth Rights." Find more from that issue here.

Raleigh, N.C. — At first glance, it looked like a church dinner or a family reunion picnic. Women and men sat in the grass on a sunny afternoon, relaxed, rocking babies and humming along with a string band that played under a blue-and-white canopy. Friends hugged each other, exchanged pleasantries about the warm weather, speculated as to the chances of rain.

But the crowd of 5,000 hadn’t come to relive old times. They had come to revile old times and talk about the future — the future of legalized abortion and other reproductive rights.

“Nineteen-ninety is the year we have to flex our electoral muscle, and we will,” said Ruth Ziegler, executive director of the North Carolina chapter of the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL).

“The next chapter of of our struggle will be written with the ballot, and we are the authors,” said state Representative Anne Barnes.

The speakers and demonstrators at the “Stand Up for Choice” rally congregated near the General Assembly building to send a message to the state’s lawmakers: If you pass laws that restrict abortion now, we’ll remember in the November elections.

Across the South, pro-choice groups have been sending the same message. And legislators are listening.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled last summer that states may limit abortion, some 35 state legislatures have debated the abortion issue. And despite its conservative reputation, the South has proved to be a stronghold for the pro-choice movement. In fact, Southern states have handed the movement some of its most significant victories:

▼ In Virginia, voters elected Doug Wilder governor after he ran on a strong pro-choice platform.

▼ In Florida, state lawmakers stunned Governor Bob Martinez by walking away from a special session he called without passing a single restriction on abortion.

▼ In Alabama, the legislature adjourned without passing any of the restrictive abortion measures anti-choice forces had lobbied for.

▼ In Mississippi, Governor Ray Mabus vetoed anti-choice legislation, calling it too restrictive.

▼ In Georgia, the legislature defeated five anti-abortion measures, including a bill to prohibit public spending on abortion except when the mother’s life was in jeopardy.

Pro-choice activists attribute such victories to a growing emphasis on electoral politics. Polls show that many Southerners resent the prospect of government interference in their personal lives, and pro-choice forces across the region are working to harness that outrage in the November elections. Slowly but surely, they have pushed abortion to the top of the political agenda, forcing candidates in state and federal elections to state their views. Voters are learning that decisions they make at the ballot box affect decisions they make in their bedrooms.

“Politicians can no longer duck it or evade it or flip-flop back and forth,” said Robin Davis of the North Carolina chapter of the National Organization for Women. “We need to know what their stand will be before we vote.”

Choice = Conservative

The shift to an electoral strategy gained momentum on July 3, 1989, when the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services. The decision gave states the authority to restrict abortions, undermining the historic Roe v. Wade ruling that legalized abortion in 1973.

When the Webster decision was handed down, anti-abortion forces looked to the South, hoping to translate the region’s tradition of religious fundamentalism and conservative politics into antiabortion laws. But a year later, the coveted defeats have not materialized. Instead, Southerners have mobilized overwhelming grassroots opposition to changes in abortion laws.

“What’s happened in the pro-choice movement since Webster is unbelievable grassroots support in the South,” said Loretta Ucelli of the national NARAL office in Washington, D.C. “I think there has been some sense that because the South is conservative it would not be prochoice. But pro-choice is conservative. People don’t want government making decisions in their personal lives.”

Kerri Milam, executive director of the Georgia chapter of NARAL, agreed. “It’s a civil liberties issue to a lot of people in the pro-choice movement. I’ve heard a lot of people say, ‘If I had to make a decision, I wouldn’t have an abortion, but I believe in a person’s right to choose.’ That is a historically conservative Southern attitude — there are some decisions that were constitutionally intended to be left to the individual.”

Despite the widespread support, pro-choice forces in the South knew they faced a tough fight after Webster. A 1989 NARAL report showed that only North Carolina and Virginia had pro-choice majorities in both legislative houses, and only Virginia had a pro-choice governor. Eleven states required minors to obtain parental consent before abortion, and ten provided funds for abortion only if the mother’s life was threatened.

State by state, organizers began to target key races and build grassroots support. The first signs of energy came from Virginia, where abortion proved a key issue in the governor’s race last fall.

Even before Webster strategists for Democratic candidate Doug Wilder had planned to contrast his pro-choice stance to Republican Marshall Coleman’s anti-abortion mindset. They knew abortion would generate heated rhetoric, but they were unaware the Supreme Court was about to totally reconstruct the political landscape.

“In terms of strategy, it was an issue we had looked at,” said Paul Goldman, Democratic Party chair in Virginia. “We saw the GOP positioning itself as dictating to the woman — that the woman, the doctor, the family had no right in the decision. What the Supreme Court decision did was bring the issue right to the forefront of the public political debate. Nobody could have predicted that.”

Wilder’s margin of victory was narrow — 6,741 votes out of 1.8 million — but strategists are convinced his abortion stance drew support from Republicans and Democrats, young and old, and residents from the suburbs to the Appalachians. Wilder appeared to champion growth and progress, while Coleman voiced vehement opposition to abortion, even in cases of rape or incest.

“Abortion became symbolic of ‘Do you want to go forward, or do you want to go back?,’” Goldman said. “Our basic plan was the future versus the past — the new mainstream versus extremism.”

Sunshine Victory

The first legislative showdown following Webster took place in Florida — and it provided an unexpected pro-choice victory. Governor Robert Martinez, a Roman Catholic, called a special session of the legislature, openly acknowledging his desire to kill legalized abortion.

At first, pro-choice advocates in Florida reckoned they had two enemies to combat: Martinez and public apathy. “We figured we’d have to go out and blow horns and beat drums to convince people of why the Webster decision was important,” said Janis Compton, executive director of the Florida Abortion Rights Action League (FARAL). “That wasn’t the case.”

Instead, pro-choice support erupted within hours after Webster was announced. People called the FARAL office late into the night to express their outrage and offer to volunteer. Within three days, Compton had 150 phone messages to return. When Martinez called the special session, the volume of calls increased, and public anger intensified.

“What we saw happening in Florida was grassroots,” said Compton. “We saw ad hoc pro-choice groups springing up in areas where there were literally nothing but cows and trees. Thousands of phone calls went to the governor’s mansion. It was very spontaneous. It caught us all by surprise.”

Pro-choice supporters volunteered to go to Tallahassee to talk to legislators, and professional lobbyists offered to work without salary. Community residents staged house meetings to educate their neighbors about the issue. “The message was the same,” Compton said. “Who is going to decide? Is it going to be the politicians or is it going to be you?”

A week before the legislative session began, FARAL mailed 12,000 pink postcards to supporters. The message: call your representatives. Tell them you’re watching, and you want the law left alone.

When the legislature convened on October 10, everyone predicted a down-and-dirty fight that might drag on for weeks. The governor’s allies introduced seven separate bills to restrict abortion rights. All seven promptly died in committee, and lawmakers headed home on October 11.

“The session was supposed to be heated and ugly,” said Compton. “Everybody went home stunned.”

Seven months later, Martinez delivered his State of the State message. He talked about drugs, transportation, economic development, and workers compensation. He never mentioned abortion.

No Ban

In Alabama, abortion opponents also expected legislators to quickly and overwhelmingly approve a law banning abortions. They introduced an “Unborn Children’s Life Act” specifying that “each human life begins at conception” and an “Abortion Regulatory Act” requiring that women seeking abortions be given materials urging them to “consider carrying your child to term . . . before making a final decision about abortion.”

As in Florida, however, the measures failed. Five bills died, and one was postponed indefinitely after emotional debate the last day of the session. On April 23 the legislature adjourned without declaring that life begins at conception.

Edward Higginbotham, a NARAL organizer in Alabama, credits a vocal grassroots movement for the victory. “Some legislators, especially rural legislators who imagined they never had any depth of pro-choice in their district, began to get a lot of pro-choice letters,” he said. “I think that made some people uncomfortable about voting for anything really restrictive.”

Alabama’s refusal to adopt restrictive legislation sent a signal nationwide. “The thinking was that Alabama would buy into it right away,” said Loretta Ucelli of NARAL, “but that didn’t happen.”

Ucelli and others also note, however, that the pro-choice movement has suffered some setbacks in the South. North Carolina slashed its abortion fund for poor women in half last year. West Virginia lawmakers voted to end state-funded abortions for poor women, except in cases where the mother’s life is in danger. And South Carolina passed a bill requiring parental consent for abortions for women under 17.

Nevertheless, pro-choice advocates say such measures might have been worse. In South Carolina, for instance, the legislature modified the parental consent bill to force parents who deny their daughters an abortion to bear financial responsibility for the child until age 19. Lawmakers also killed a bill that would have forbidden a woman to have an abortion without her husband’s consent.

Balance of Power

With the November elections approaching, Southerners are blueprinting plans to elect more pro-choice candidates and more women.

The National Organization for Women calls its campaign the “feminization of power” — encouraging women to run for every state office in the nation. “The reality is that government is controlled by men,” said Patricia Ireland, NOW vice president. “Women make up less than 17 percent of the state legislatures. We must have better representation in the legislature to protect our rights.”

Florida will be a key state in the 1990 elections — not just because it was the center of one of the first pro-choice victories, but also because it boasts 21 electoral votes. NOW has organized a special effort to recruit female candidates to run for state offices, and FARAL has targeted Governor Martinez for defeat. “We’re working to get Martinez out,” said FARAL director Janis Compton. “You cannot do what he did and stay in office.”

In addition to fighting its enemies, FARAL is supporting its friends. The group is backing Elaine Gordon, a Miami state legislator who helped defeat the abortion bills in the 1989 legislative session, and Leander Shaw, a judge who wrote the opinion that state privacy laws protect women’s decisions on abortion.

Other Southern states are constructing strategies of their own to defeat anti-abortion candidates:

▼ In Tennessee, pro-choice activists are using paid organizers to recruit female candidates to run for office.

▼ Alabama pro-choice leaders are encouraging voters to oust legislators who supported abortion restrictions in the 1990 session.

▼ In Arkansas, the Committee for Reproductive Choice is gathering signatures to place a proposition on the 1992 ballot forbidding the state to “interfere with any woman’s personal reproductive decisions.”

On the Phone

Some of the most comprehensive electoral groundwork has been laid in Georgia, where a coalition of eight pro-choice groups is recruiting candidates to run against state lawmakers who oppose abortion.

“We can’t change the entire general assembly in one year,” said Mary Hickey, director of the elections project. “But if you are on the anti-choice side, we can target you and will, in some cases, beat you. Races can be determined on this issue. We are organized and can make a difference.”

To identify where candidates stand on abortion, the Georgia NARAL chapter (GARAL) plans to conduct one-on-one interviews and mail questionnaires to the 256 candidates in state races. Those who claim to be pro-choice will be asked to clarify whether they support public funding of abortion for poor women and the right to choose abortion under all circumstances. “We’re not going to accept at face value that they’re pro-choice,” said Kerri Milam of GARAL.

Candidates who support choice can count on financial backing from pro-choice forces, said Hickey. The Vote Choice Political Action Committee raised $30,000 in its first two months, and hopes to contribute $100,000 to pro-choice candidates this fall.

Georgia organizers are also working to identify voters likely to support abortion rights. The effort is patterned after programs in New York and Minnesota that identified potential pro-choice voters based on party affiliation and voting history, and then educated them on the views of each candidate.

In North Carolina, pro-choice organizers are conducting an extensive voter identification drive in a single district. The goal: defeat state Representative Paul Stam Jr. of Apex.

Elected to the legislature in 1988, Stam sponsored a bill restricting abortions and engineered an effort to slash the state abortion fund for poor women. The North Carolina NARAL chapter calls him “the ringleader of the anti-choice movement in the legislature and across the state.” The Independent, a weekly Durham newspaper, dubbed him “the prince of pelvic politics.”

NARAL is convinced Stam can be defeated. He was the first Republican representative elected from District 62, a 200-square-mile area of farms and upscale subdivisions where Democrats outnumber Republicans by a 2-to-1 margin.

To defeat Stam, NARAL volunteers have worked a phone bank since January, personally contacting more than 5,000 of the 33,171 registered voters in District 62 — especially Republican women, GOP baby boomers, and newly registered Democrats. NARAL believes a Stam defeat will send a clear message to anti-abortion forces nationwide.

Although campaigns in each state use different methods to ascertain which voters and candidates are pro-choice, the strategy for getting out the message is the same nationwide: urging pro-choice voters to contact their representatives as often as possible.

“I want you to commit today to talk to your legislators,” Patricia Tyson, executive director of the Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights, told the crowd at the pro-choice rally in North Carolina. “Talk to them at their offices. If they’re not there, talk to them at church. If they’re not there, talk to them at home. If it means getting on their front porch, then come to their home. If that doesn’t work, do what people did to my husband when he was an Alabama legislator — talk to their mother.”

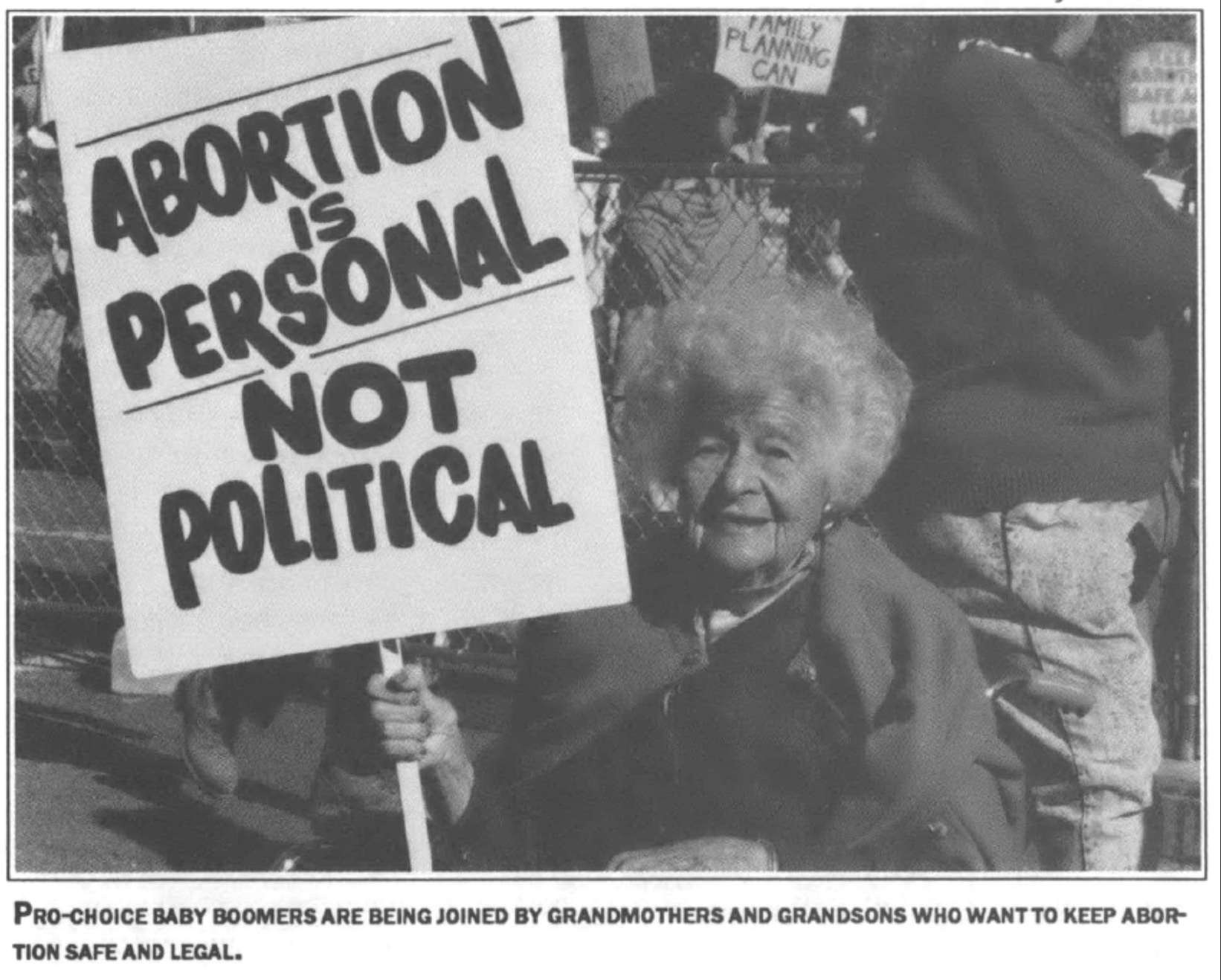

Grandmothers and Grandsons

As they comb the South for support, they are finding it in some unusual places. Pro-choice baby boomers are now being joined by grandmothers who remember when some states outlawed birth control for married couples and by grandsons who can’t remember when abortion wasn’t legal.

The diversity of the movement was evident at the North Carolina rally, where college students stood under a banner made from a bedsheet and signed by dozens of their friends. Nearby a blond woman in her thirties balanced a baby on one hip and a sign reading “Another Woman for Choice” on the other. A gray-haired woman in a neat striped shirt and denim skirt held a sign that read “Menopausal Women Nostalgic for Choice.” An elderly gentleman wiped sweat from his forehead with a white cotton handkerchief, while a young man in camouflage pants and a Durham Bulls baseball cap listened attentively to speakers.

Pro-choice activists are accustomed to the support of older women who still remember the days when abortions were performed on kitchen tables with coathangers. But the support of younger men and women comes as a surprise.

“It used to be much harder to get younger women involved in this,” said Janis Compton of Florida. “It was not something they could identify with on a gut level. Women under 30 have grown up with abortion as an option. No matter how they felt about it, they knew if worse came to worst, they could have an abortion. When they were really confronted with the possibility in July of losing that right, they became real angry and real vocal.”

Polly Guthrie, a student at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, is one who became angry and vocal. She helped organize a campus pro-choice rally that drew more than 1,000 participants and celebrity speakers, including actor Richard Dreyfus. The rally rivaled the Vietnam protests of the 1960s in enthusiasm and size. Afterward, 200 people registered to vote.

“We as students are probably the most inactive voting constituency in the country and probably the constituency that has the most to lose if abortion becomes illegal,” said Guthrie. “Students have surprised the people organizing on the choice issue. This is an issue that is really moving students. When I take a petition around, I have people overhearing me and coming up to sign.”

Students like Guthrie see abortion in its wider context. “To me, I make a connection between abortion as an issue of women’s health and reproductive freedom,” she said. “This is one link in a chain — and when I see one of those links in danger, it shakes the whole system. We’ve had many rights that we ’ve taken for granted. I don’t think we can afford to become complacent.”

Despite the growing grassroots support and the string of legislative victories, pro-choice organizers say they won’t become complacent. Every time an election is held, they say, women’s lives and individual liberties are at stake.

“The only way we’re going to protect the right to choose is through the electoral process,” said Loretta Ucelli of NARAL. “Since Webster handed this issue to the politicians, we’ve got to elect pro-choice legislators, governors, congressmen, and a president who will appoint pro-choice Supreme Court justices. Until we do that, the right to choose is in jeopardy.

“We’ve been extremely successful, but we live every day with the reality that because of Webster, all it takes is one anti-choice bill out of one anti-choice legislature and signed by one anti-choice governor, and pro-choice starts to unravel,” Ucelli added. “We’ve had victory after victory, but the other side only needs one victory. The greatest victory we can achieve is to maintain the status quo.”

Tags

Barbara Barnett

Barbara Barnett is a writer/editor living in Raleigh. A former journalist, she was a reporter and editorial writer for The Charlotte News and The Charlotte Observer. She has a master’s degree from Duke University in writing and women’s studies. In addition to Southern Exposure, her fiction has appeared in The Journal for Graduate Liberal Studies, Hurricane Alice: A Feminist Quarterly, and Voices.