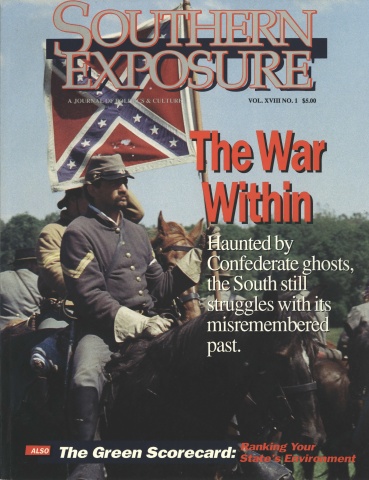

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 18 No. 1, "The War Within." Find more from that issue here.

Among the startling developments that have swept Southern politics in recent decades, none has been more ironic than the increasing strength of a coalition of white moderates and blacks within the Democratic Party. Once known as the “Party of White Supremacy,” the Democrats have moved increasingly toward the national mainstream in search of a broader base of support.

While the biracial alliance in the party is often strained, it is not without precedent in Southern history. In fact its roots date back to the Civil War. The fighting forced many non-slaveholders to evaluate the political costs of their commitment to white supremacy. Tens of thousands of white small farmers in the uplands eventually came to view the newly emancipated “freedmen” as potential allies against the power of the wealthy planters.

A cherished belief in the popular mythology of Southern history has long been the essential unity of the white South, especially during the greatest crisis of the region’s history: the Civil War. Non-slaveholders joined with their more fortunate neighbors to preserve states’ rights and slavery from Northern interference, and held out until overwhelmed by sheer numbers — or so the story goes. But historians are currently dispelling this myth, demonstrating that there was substantial anti-Confederate sentiment throughout the South, and widespread opposition among whites in the mountains of Arkansas, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

“Kiss There Hine Parts”

In 1860, three-quarters of Southern white families owned no slaves. Much of the non-slaveholding majority was concentrated in mountainous areas, where poor soil and transportation made the land unsuitable for plantation production. The South thus developed a “dual economy.” Plantations dominated commercial agriculture with the staples of cotton, tobacco and sugar, while the rest of the region grew food crops and raised livestock. Particularly in the Appalachian and Ozark mountains, small farms owned by white “yeomen” dominated the social landscape. These enclaves were geographically and culturally distinct, with a strong identity that differed from the rest of the South.

Before Southern states seceded from the Union in 1861, most upland yeomen supported slavery and shared the common value of white supremacy. Most identified with the pro-slavery Democratic party of Andrew Jackson, seeing the westward expansion of slavery as beneficial both to themselves and their region.

Despite the support for slavery, many farmers distrusted the slaveholder elite from the rich plantation regions. In state after Southern state, representatives of the highland regions struggled against those of the plantation belt over voting districts, taxation, and symbolic issues like the location of state capitals. Most of the upland small farmers responded to Jacksonian rhetoric of equality and preferred to be left alone by both state and national government — and the tax collector. Mountain yeomen also resented the superior airs of their slaveholding social betters, often cursing black slaves and their wealthy masters with the same breath.

The first critical split in the Southern social structure came with the election of Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans, who sought to restrict slavery’s spread with the long-term goal of its extinction. Most slaveholders concluded that decisive action was necessary, and a wave of popular fear and outrage strengthened their hand. Starting with South Carolina, the seven Deep South states called for popular elections of delegates to state secession conventions.

Most of the plantation regions elected delegates pledged to “immediate secession,” but the upland areas of northern Georgia and Alabama defeated these candidates by huge margins. Instead, they voted for “Cooperationists” who counseled a vague “wait and see” attitude. The Cooperationist label covered a variety of views, from conditional secessionism to outright Unionism. But it is significant that the upland voters demonstrated the most hesitation at dissolving the federal Union — in the very areas where wartime disaffection would be most pronounced.

Several of the resulting secession conventions were raucous affairs, dogged by bitter controversy. One Alabama delegate challenged the secessionists to battle “at the foot of our mountains” if the state seceded without ratification by the electorate. In both Georgia and Alabama the conventions were clearly divided, and only the example of neighboring states — and wholesale electoral fraud — carried Georgia out of the Union.

In the upper South states of North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas, the split was even clearer. Mountain regions overwhelmingly elected anti-secession delegates, who were able to dominate the conventions called to decide the issue. For months the upper South remained in the Union, hoping that some compromise by the new administration would reunite the nation.

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s subsequent call for troops undermined such hopes. The upper South states seceded — though they did so with substantial opposition. Almost three months after the outbreak of war, the mountain region of east Tennessee returned a large majority against secession.

Even after the state seceded, a public convention proclaimed the area’s continuing loyalty to the Union. Secession, observed Union supporters, had been “marked by the most alarming attacks on civil liberty” and threatened the “last vestige of freedom.” A Confederate general dismissed the Unionists as “ignorant, primitive people,” and others emphasized their modest wealth and rural isolation. In fact, secession was far more popular in east Tennessee’s cities and towns than it was in the rural hinterland. So hostile were the mountains that the governor eventually recommended a garrison of 14,000 men to occupy the region.

The mountain region of northwestern Virginia also voted against secession after the outbreak of the war, and when Union troops entered the area, they met substantial popular support. The area eventually seceded from Virginia itself to form the state of West Virginia.

Farther south, the reality of secession and war induced most reluctant Confederates to abandon their misgivings, but pockets of opposition remained, even in the Deep South. As one farmer wrote from the mountains of Alabama, all the Rebels wanted was “to git you pumpt up to go to fight for their infumal negroes and after you do there fighting you may kiss there hine parts for o they care.”

Poor Wives and Children

During the first year of the war, the Confederate cause remained relatively popular, sustained by an outpouring of public emotion. Except in bitterly Unionist east Tennessee, opposition to the war was inconsistent. Even in the mountains, volunteering for Confederate service was substantial; initially the government of Jefferson Davis had more men than guns to give them. But this wave of recruitment emptied the mountains of Confederate supporters of military age, concentrating dissent in those left behind.

As the war progressed, the costs of mobilizing the region’s population and economy became more apparent — and the heaviest burden fell on the families of non-slaveholders in the mountains and surrounding foothills. The upland farms produced little in the best of circumstances, and now the war stripped away the most productive laborers. North Carolina’s governor observed that “the cry of distress comes up from the poor wives and children of our soldiers. . . . What will become of them?”

One citizen satirically recommended that the army “knock the women and children of the mountains in the head, to put them out of their misery.” Somewhere between 20 and 40 percent of North Carolina’s population required poor relief from the state. In Georgia, fully half the state expenditures were devoted to poor relief by 1864. The privation was equally intense elsewhere in the mountains, especially as battle devastated much of the region, and the overtaxed Southern supply network proved incapable of bringing in sufficient food.

The Confederate government compounded these hardships by enacting a 10 percent “tax-in-kind” on all agricultural products beyond the minimum needed for survival, as defined by Confederate officials. Impressment units also seized food needed by the government at nominal prices — a system that the Secretary of War described as a “harsh, unequal, and odious mode of supply.”

Such seizures, combined with rampant inflation that reduced military pay to derisive levels, threatened the dependents of Confederate soldiers with privation. Hunger was indeed common among the soldiers’ families, especially late in the war. The impact was graphically illustrated by a soldier’s letter from his desperate wife: “I would not have you do anything wrong for the world, but before God, Edward, unless you come home we must die.” Edward deserted but was later captured, only narrowly escaping execution.

Draft Dodgers

During 1862, a series of military defeats combined with unpopular Confederate policies to undermine the appeal of Southern nationalism. Troubled by the increasing scarcity of volunteers, the Davis administration implemented a draft and forcibly re-enlisted all those who had joined the army the previous year.

Compounded by the growing war weariness, the draft law became the focus of resentment. The law allowed substitution, a boon to those wealthy enough to hire replacements. In addition, the Confederate Congress exempted one adult white male for every 20 slaves owned, so planters and overseers essentially escaped conscription. Little wonder that the cry went up that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” In the words of one Confederate Congressman, the exemption for planters earned “universal odium,” and its influence upon the poor was “calamitous.”

Desertion increased drastically after the act, and by the end of the war over 100,000 soldiers were reported as absent without leave. The Confederacy was far less successful at recapturing its deserters than was the Union, for only one out of five ever returned to the front. All this had a grave impact on the upcountry. Deserters headed for the mountains, among other rugged locales, where capture was most difficult. Since these areas were the homes of the poorest farmers in the South, the growing opposition to the Confederacy had both a regional and class character. Their increasing numbers presented the South with major difficulties in retaining public order.

Confederate efforts to recover deserters and enforce draft laws led to escalating conflict in the more isolated portions of the mountains and upper piedmont, and even in non-plantation areas closer to the Confederate heartland. Deserters joined with those who had been lukewarm to the Confederacy to dominate whole counties. As conscription agents entered the upland in force, bands of deserters and draft resisters offered battle rather than accept capture.

The Confederacy could ill afford to transfer troops from the front, and the “Home Guards” were often outmatched. In Alabama alone, according to a Confederate estimate, 8,000 to 10,000 armed deserters or “Tories” roamed the northern part of the state. One recalled that after his desertion, he “wrote the boys that they had better come home, which many of them did.” Opposition to the Confederacy occurred openly. In one case a Unionist mob liberated draft evaders from jail, prompting Confederate authorities to arrest hundreds.

Across the South these anti-Confederates found it impossible to tend their farms. Some became outlaws, living off their Rebel neighbors. Others joined the invading Union troops. Over 30,000 white Tennesseans entered the Union Army, mostly from the eastern part of the state. As far south as Alabama, almost 3,000 entered federal service, nearly all of them from the mountains or from the poor “wiregrass” counties to the southeast.

Violence of an unusually savage nature escalated in the upcountry. In east Tennessee, guerrillas torched railroad bridges in November 1861 in anticipation of a federal invasion. Hundreds of arrests ensued. The Unionists hid “among the fastnesses and caves of the mountains,” while the Rebels hunted them “day and night like wild beasts.” The Confederate authorities hanged five of the perpetrators, leaving their bodies dangling for days to overawe the hostile populace.

In the mountains of North Carolina, the military arrested 13 suspected Union partisans in 1863 and then gunned them down in death-squad fashion. Private feuds also erupted in the politically charged environment, and the resulting violence would dog the region for years.

The rigor of Confederate efforts to maintain order offended upland farmers’ firm belief in local governance. They had seceded to protect states’ rights from Yankee tyranny, and now they encountered heavy-handed action by their own increasingly centralized government. While the yeomen were not the only Southerners who resented the actions of the Confederate government their woes — and the efforts to address them — encouraged the growing conflict between state and national authority.

In Georgia, for example, Governor Joseph Brown was long identified with the yeoman farmers of the northern part of the state. Brown publicly challenged the legality of the draft, and when rebuffed by the courts, used his power as governor to exempt large numbers from conscription. He also enrolled thousands in the state militia, thus keeping them out of the Confederate Army. “We must maintain a producing class at home to furnish supplies to the Army,” he observed, “or it becomes a question of time when we must submit.” Immediately after the fall of Atlanta in September 1864, Brown sent the militia home to gather their crops, to the horror of the army command.

A Peace Movement

By the middle of the war, the Davis administration was unpopular, and opposition candidates triumphed throughout the region. As one observer in north Alabama observed, the 1863 elections demonstrated a “decided wish amongst the people for peace as but few of the old members were returned.” The Confederate Congress actually refused to seat several of the new members for being traitors.

The most militant open opposition was demonstrated in North Carolina, where William Holden ran for governor on a “peace platform” in 1864. Although initially expected to win, military intimidation and a last-minute revelation that Holden was negotiating with President Lincoln led to a backlash. Holden was defeated, but he ran strongly in the mountains.

Organized peace sentiment even appeared within the Confederate army. Many of the conscripts from the Alabama hill country who made up “Clanton’s Brigade,” for example, came under “home influences” and joined a clandestine Peace Society in 1863. Some 70 were arrested for mutiny. An investigation revealed that the “soldiers from the low and poorer classes regard this as the only means of ending the war, of which they are so tired they will accept peace on any terms.” General Clanton thought the men should be shot as traitors, but by 1865 the military command was conducting peace negotiations of its own. As one north Alabama Unionist observed, there was a “universal anxiety to have the war come to a close with or without Jeff Davis’s consent.”

By the last days of the war, armed anti-Confederates dominated much of the mountain region not already occupied by Union forces, and the Confederate army and home front approached collapse. After the Battle of Nashville in December 1864, the defeated army of General Hood simply disintegrated in the course of retreat. General Lee himself observed that during the siege of Petersburg, “hundreds of men are deserting nightly and I cannot keep the army together unless examples are made of such cases.” When news of the surrender at Appomattox arrived, the response of much of the Southern public was relief rather than despondency.

But the pleasure of upcountry Unionists was short lived. Most assumed that peace would bring physical security and political supremacy, but conflict continued in many areas. The demobilization of the two armies brought partisans of both sides into close proximity. Union deserters, who had dominated much of the mountain region, often found themselves outnumbered by returning Confederate veterans determined to pursue personal vendettas for what had transpired in their absence.

Instead of easing the misgivings of Southerners who had supported the Union, presidential Reconstruction initially allowed many ex-Confederates to retain state power. In one instance, local officials admitted that Union men were shot upon sight for three months after Appomattox. Local juries also prosecuted Union men for wartime thefts and other misdeeds. Most alarmingly, ex-Rebel officials often discriminated against Union men in the allocation of the vast food relief supplied by the federal government. As a Tennessee newspaper observed, the “people reported to be starving” were the “political brethren of these Radicals,” and thus they ought not to look to their fellow Southerners for aid.

Anti-Confederate Southerners responded angrily to Rebel persecution. Throughout the mountains they organized for resistance, often in clandestine clubs called “Union Leagues.” In 1866, one Union League activist in the mountains of Alabama wrote that they “could no longer do without troops unless you allow the loyal men to kill the traitors out.” This was more than talk. In north Alabama alone conflict between Unionists and ex-Confederates resulted in several pitched battles in the two years after the war.

By 1867 the Unionist minority was desperate enough to decide on a drastic course: They reached out to the newly freed slaves as allies, thus becoming the “scalawags” of Reconstruction lore. Much of the Unionist following now supported black suffrage. In Tennessee, for example, Governor William Brownlow’s hard-pressed Unionist government had enacted equal suffrage voluntarily. In the rest of the region, tens of thousands of white Southerners welcomed military Reconstruction laws that gave blacks the vote, seeing them as the only means by which loyal men could rule.

Thus the Civil War helped forge a biracial lower-class alliance that changed the face of Southern politics. Far from uniting whites under the Confederate banner of white supremacy, the war heightened the class and regional conflicts that already existed within white society. The yeomanry of the hills had been reluctant to launch the Confederate nation, and the unequal demands of the war effort brought thousands into open opposition. Their militancy eventually brought many to the great heresy of the era — embracing ex-slaves as political allies after the war. Both the defeat of the Confederacy and the rise of the biracial alliance hinged on the critical reality of the Civil War: the inherent difficulty of persuading small farmers to die to preserve someone else’s slaves.

Tags

Michael W. Fitzgerald

Michael Fitzgerald is a professor of history at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, and author of The Union League Movement in the Deep South (LSU Press, 1989). (1990)