Ruling the Roost Introduction

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Kentucky Fried Chicken. Chicken McNuggets. Chicken and biscuits. From the time we take our first bite of chicken as children, primal instinct and mass marketing tell us that anything we eat with our fingers must be finger-lickin’ good. We happily abandon the clumsy utensils of modem civilization for the carnal pleasure of holding our own food — without so much as pausing to consider the source of what we are eating.

As consumers have grown more health conscious in recent years, chickens and turkeys have overtaken beef and pork as the main dish of choice on American dinner tables. In 1986, consumers ate more poultry than beef for the first time ever. The average American ate 61.5 pounds of chicken last year — up from only 13.8 pounds in 1955.

The switch to a healthier diet has transformed the poultry business from a barnyard hobby into a giant industry — and the growth has been especially dramatic in the South. Poultry is now bigger than peanuts in Georgia, tobacco in North Carolina, cotton in Mississippi, and all crops combined in both Alabama and Arkansas. The industry is the biggest agribusiness in the region today, employing 20,000 contract farmers and 150,000 workers in poultry slaughterhouses and processing plants.

Yet what appears to be a low-cost, low-fat substitute for beef may not be the healthy alternative we thought it was. As the articles in this cover section of Southern Exposure reveal, the poultry industry treats its chickens better than it treats the people who raise, package, and eat them.

Farmers under contract to big poultry companies call themselves “serfs on their own land.” Workers who kill and process chickens — from white women in the Ozarks to black women in the Deep South — describe their work as “modem slavery.” And consumers who eat poultry are being exposed to millions of sick birds every year. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that 40 percent of all chickens we buy are contaminated with salmonella, a bacteria which poisoned an estimated 2.5 million people last year — including 500,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths.

Although the poultry industry is based almost entirely in the South, its influence reaches worldwide. The Kentucky Fried Chicken in Beijing rang up more sales last year than any of the company’s other 7,700 franchises. Don Tyson — the Arkansas-based chicken tycoon who supplies McDonald’s with most of its McNuggets — expects his exports to Asia to hit $100 million this year.

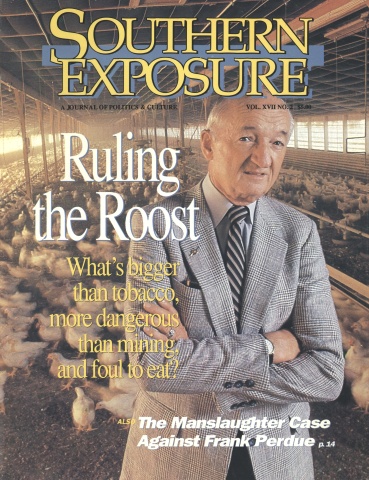

Many of the articles in this section focus on Frank Perdue, the chicken producer who has spent millions cultivating a “tough man” persona on television. Perhaps more than anyone else, Perdue has given the poultry business a human face — yet he repeatedly downplays the ways the industry is hurting farmers, workers, and consumers.

In a statement prepared for a congressional hearing in June, for example, Perdue testified that less than one percent of his workers suffer from the crippling hand and arm diseases known as cumulative trauma disorders. Yet federal officials say poultry companies routinely “underreport” the disorders in an industry ranked as more dangerous than coal mining. In a study of skin diseases at Perdue’s largest North Carolina plants, federal investigators found “apparent underreporting . . . for workers in all departments.”

In preparing this section, we also discovered that an untold story from Perdue’s personal life offers an indication of how he maintains a clean image in the midst of such a dirty business. According to a federal report obtained by Southern Exposure, Perdue was charged with recklessly and negligently killing a man in a highway accident 15 years ago — yet he walked away without a trial. The story of how Perdue escaped prosecution and purged court records of all reference to his manslaughter charge appears on page 14.

Although Perdue has made himself a public figure, he is not alone: the industry as a whole has recklessly and negligently injured communities across the region. Some of the largest poultry firms have driven family farmers out of business while reaping huge tax breaks as “family farms.” They have polluted drinking water while pressuring legislators to exempt them from public nuisance laws. They have crippled workers while vaccinating their chickens. And they have fought to cut federal inspection while turning out increasingly contaminated food.

Perhaps, in the final analysis, it is those of us who buy chicken in supermarkets and restaurants who must hold the industry accountable for the sickening way it mistreats our communities, chicken farmers, poultry workers, and consumers.

After all, as the saying goes, we are what we eat.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.