This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Eighty-three years ago Upton Sinclair shocked the public with his description of the Chicago meatpacking industry in The Jungle: the slaughter of diseased animals, meat covered with excrement, and workers who fell into lard vats, never to return.

Except for disappearing workers, the current slaughtering practices in the meat and poultry industry today are remarkably similar to those Sinclair documented in 1906. According to poultry workers, federal inspectors, and public health officials, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has cut its inspection staff, lowered health standards, and systematically cracked down on employees who try to inform the public about contaminated food.

What’s more, observers say, USDA is gradually abdicating the responsibility for food safety it assumed after the public uproar over The Jungle by deputizing the poultry industry to inspect itself.

The relaxed inspection practices — known as the Streamlined Inspection System — are literally maiming workers and killing consumers. Workers in poultry processing plants are frequently crippled by unsafe machinery operated at reckless speeds, and USDA routinely puts its stamp of approval on contaminated birds. As a result, the number of cases of salmonella, the most serious form of food poisoning from poultry, has risen to 2.5 million a year — including an estimated 500,000 hospitalizations and 9,000 deaths.

The Driver’s Seat

The roots of the “streamlined” inspection policy can be traced to the early 1980s, when the Reagan administration began deregulating private industry. Dr. Robert Bartlett, a top-ranking Agriculture Department official, frankly described the new policy in a 1981 memorandum to his staff: “The political climate is such that the special interest groups supporting the meat and poultry industry have won and now have the ear of Washington. They ‘paid their dues’ and are now in the driver’s seat. . . . The consumer base has disintegrated. We must be versatile and adjust to this new challenge.”

One of the most obvious adjustments was a cut in the number of inspectors. At the beginning of 1981, the USDA roster called for 5,995 full-time slaughter inspectors. Although meat and poultry consumption has increased since then, the agency’s current budget contains slots for only 5,020 inspectors. During the same period, the number of headquarters bureaucrats jumped from a handful to nearly 1,000.

The Agriculture Department also moved unofficially to lower inspection standards, either through word of mouth or informal memoranda. For example, inspectors once condemned all birds with air sacculitus, a disease that causes yellow fluids and mucus to break up into the lungs. Although the law hasn’t changed, USDA inspector Estes Philpott of Arkansas now estimates that he is forced to approve 40 percent of air sac birds that would have been condemned 10 years ago.

Other whistleblowing inspectors report similar experiences. In a sworn affidavit, retired inspector Albert Midoux described how he was reprimanded in 1987 for ordering the shutdown and cleanup of a room where the maggots were so thick that workers were slipping on the floor. Midoux recounted how 10 years earlier he had received a commendation for taking the same action.

The relaxed standards fly in the face of a rising concern over public health threats from food poisoning. In 1987 testimony before the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Edward Menning of the National Association of Federal Veterinarians warned that food poisoning is rising to unacceptable levels. As many as 81 million Americans suffer from yearly bouts of diarrhea, most commonly caused by contaminated poultry. And those hardest hit by the rise in salmonella poisoning have been the most vulnerable — the elderly, the very young, and those with immune deficiencies.

USDA doesn’t deny that food poisoning has increased — it simply advises consumers to treat all poultry as if it’s contaminated. The agency recommends extensive precautions in the kitchen: wearing rubber gloves when handling chicken, making sure the bird doesn’t touch other food, and sterilizing any surface that comes into contact with uncooked poultry.

In effect, consumers are being told to regard all poultry as a potential health hazard. “It’s not fair to expect consumers to behave as if they’re decontaminating Three Mile Island when all they want to do is cook their Sunday dinner,” said Kenneth Blaylock, president of the American Federation of Government Employees.

Grade A Censorship

Given its response to contamination, it is not surprising that USDA has tried to keep secret the real goal of its “modernization” policy — turning federal responsibility for food safety over to the industry itself. The first step in the new program was censorship. USDA reviewers learned they no longer could write reports about contaminated meat that was illegally approved and sold to consumers. Eight veterinarians who persisted were harassed, transferred, or forced to retire.

Gag orders, censorship, and the destruction of documents that contain “bad news” have since become a way of life at USDA. As a top agency official explained in 1985 after the agency was caught destroying a report that revealed massive amounts of contaminated food had been approved, the department wants to maintain a “positive” image rather than examining “every damn little nitty-gritty thing that comes up.”

The agency made a mistake, however, when it tried to censor the reports of one review team veterinarian, Dr. Carl Telleen. Telleen is a 75-year-old safe food crusader with a grandfatherly smile and a twinkle in his eye that changes to sparks when he talks about filthy poultry. He finally retired this spring, seven years after USDA tried to force him out.

In 1982, Telleen transferred to a do-nothing office job after refusing to tone down his reports. He kept busy researching new inspection techniques — and what he learned disturbed him. Carcasses contaminated with feces, once routinely condemned or trimmed, are now simply rinsed with chlorinated water to remove the stains. According to Telleen, washing removes the outer filth, but actually embeds invisible salmonella germs into the poultry flesh or spreads them to other parts of the carcass.

Worst of all, Telleen learned, thousands of dirty chickens are bathed together in a chill tank, creating a mixture known as “fecal soup” that spreads contamination from bird to bird. Once the feces are mixed with water it creates what Telleen calls “instant sewage.” Consumers pay for the contaminated mixture every time they buy chicken: up to 15 percent of poultry weight consists of fecal soup.

When Telleen wrote an article exposing the scam, the Agriculture Department issued a reprimand and threatened to fire him for breaking its ethics code, which forbids employees from taking “any action which adversely affects public confidence in the integrity of the government.” USDA reasoned that by warning the public of food poisoning, Telleen had violated the ethics rule.

Last year, however, USDA released a study that in effect acknowledged Telleen’s only crime was telling the truth. The study conceded that washing does not adequately remove salmonella germs left behind by fecal contamination — even after 40 consecutive rinses.

Telleen remains dissatisfied, however, insisting that the only foolproof way to prevent the spread of the disease is to separate contaminated carcasses from clean birds as soon as the filth is detected. “Segregating clean food from the dirty,” he says, “has been the law of science, religion, and common sense since the Bible.”

“At Their Mercy”

What Telleen stumbled across was only one example of how the technological revolution in poultry processing has actually increased the level of contamination. According to Menning, the federal veterinarian, the poultry industry was forced to begin washing carcasses because of increased contamination caused by mechanical eviscerating machines. The eviscerators are supposed to rip intestines from carcasses, but often they rip them open and spill feces all over the body cavity.

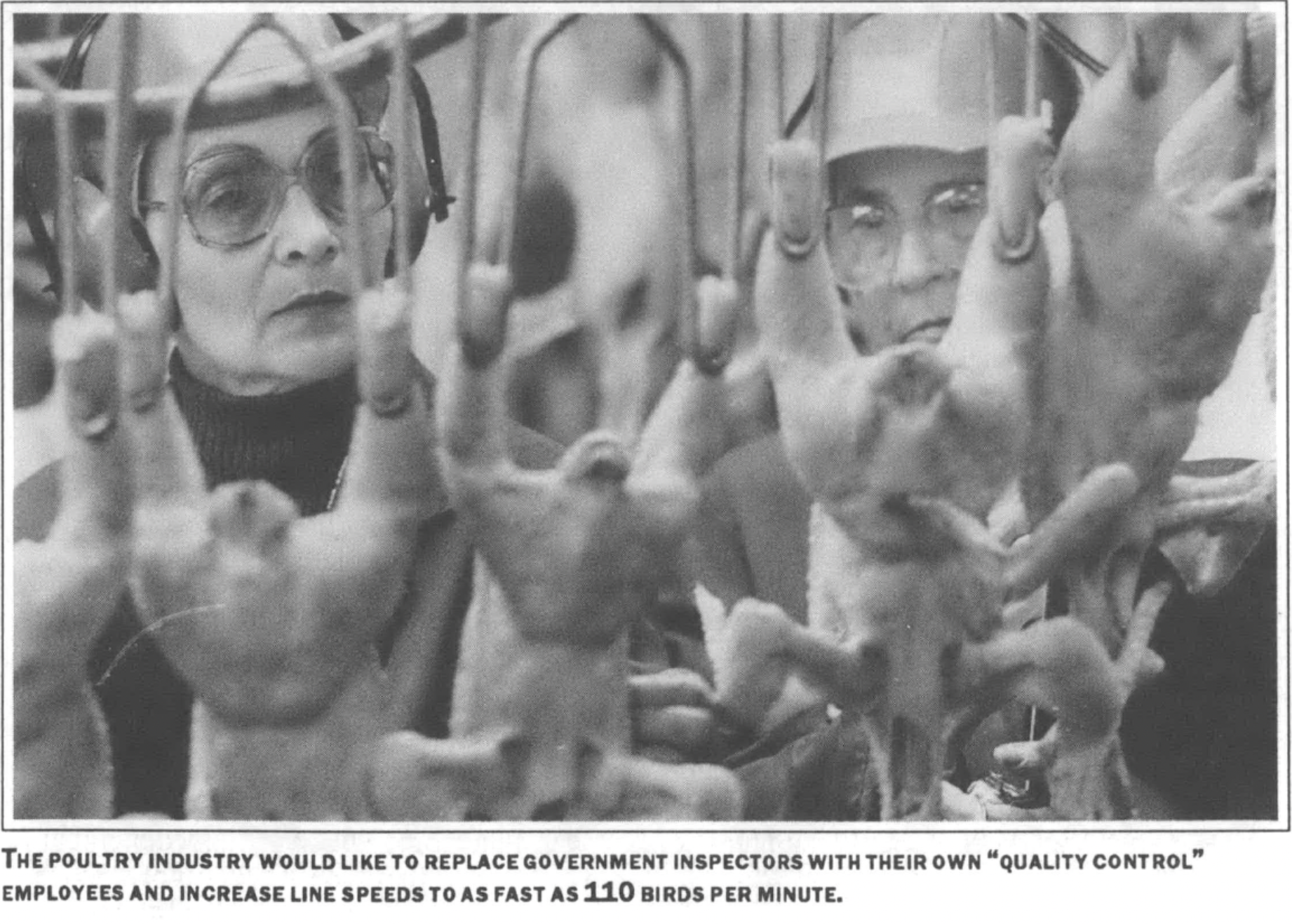

Part of the reason is the speed of the machines, which run at 70 to 90 birds per minute — nearly three times faster than a decade ago. Contamination is also exacerbated by other modem technologies like feather pickers, machines that use “rubber fingers” to pound off feathers. Unfortunately, the machines also pound dirt and manure into the skin pores.

As a result, salmonella contamination is steadily increasing — from an official rate of 28.6 percent of all USDA-approved broilers in 1967 to 36.9 percent in 1979. USDA has stopped reporting the levels, but other surveys reveal that contamination at some plants has skyrocketed to 60 percent. In 1986 the chief of federal poultry inspection admitted that levels of 58 percent at a given plant did “not surprise” him.

While expensive technology and faster assembly lines poison poultry sold to consumers, USDA is replacing federal inspectors with corporate “quality control” staffers who are permitted to vouch for the USDA stamp of approval. The new program has given the industry a rubber stamp, putting food safety in the hands of employees on the company payroll.

Unlike their corporate counterparts who have replaced federal inspectors in the defense and nuclear industries, quality control inspectors in the food industry are not required to earn professional certifications or receive federally approved training.

They are also denied the freedom to enforce the law. According to federal testimony, companies have fired quality control inspectors on the spot for reporting violations that could slow production or cause costly condemnations.

Earlier this year, quality control supervisor Donald Henley told a congressional committee how his boss informed him of his job rights after he stopped some 3,000 pounds of spoiled hams from being shipped illegally. “We don’t need you around here,” the plant owner told him. “You’re fired. Now go on and get out.”

“There was nothing I could do,” Henley recounted. “When I worked in the industry, I didn’t have the right to do the right thing.” He warned that industry inspectors “aren’t going to stick their necks out if they can’t defend themselves.”

Intent on keeping inspectors silent, industry lobbyists have vehemently opposed passage of the Employee Health and Safety Whistleblower Protection Act, a bill designed to protect employees who expose illegal practices. As Bette Simon, another poultry inspector who blew the whistle on the industry, testified at hearings on the bill, “Until Congress gives us some free speech rights in terms of our jobs, poultry companies are the law where we work. The public will continue to be at their mercy.”

On the Line

Opposition to civil rights is not surprising, many inspectors say, since the poultry industry is known for treating its workers as machines rather than human beings. Inspectors witness working con-

ditions at poultry plants first-hand, and whistleblowers describe the work as “modem slavery.”

Poultry companies allow nothing to get in the way of production, inspectors report — and the results are frequently tragic. One eyewitness signed a statement describing how a poultry worker who complained of a headache passed out and died after being denied a break:

“Maybe she died right there on the line, or maybe she hit her head when she fell, I don’t know,” said the witness, who asked not to be identified because family and friends still work at the plant. “All I know is that she had blood coming out of her eyes and ears. It was the worst thing I ever saw. I still cry just to think about it.”

Inspectors are also exposed to many of the same occupational hazards that face poultry workers on the line, such as excessive chlorine in the water used to wash chickens. Bette Simon testified that the company she worked for used solutions of up to 70 percent chlorine to bleach feces it refused to remove from carcasses. Heavy fumes from the solutions made her eyes water and skin peel from her hands. She and other workers developed lung problems, and suffered from chronic headaches and sore throats.

“You just feel sick and worn out all the time,” said Simon, relieved to have switched to a job as waitress at a truck stop.

Some of the hazards to inspectors and workers pose health threats to consumers as well. Since employees are not allowed to leave the line to go to the bathroom, they sometimes have to use the floor. Chickens that fall in the urine and excrement are routinely picked up and returned to the line. At one Southern poultry plant, inspectors reported, management would not stop the line after a pregnant woman vomited on it.

Blowing the Whistle

Even without protection, enough inspectors have spoken out so that consumers are starting to learn what they’re eating. Hobart Bartley is a former federal grader whose dissent sparked a 1987 60 Minutes expose on fecal soup. A 57-yearold farmer, Bartley earned medals for bravery in Korea and Vietnam, where he served in an intelligence unit.

Bartley was forced to retire as an inspector after he caught the Simmons poultry company trying to switch the tags and ship out 200,000 pounds of chicken packed with tumors, abscesses, broken bones, and bruises. Although USDA scoffed at the disclosures, a born-again quality control inspector at the plant described on national television how he had been ordered to falsify records allowing the company to ship products illegally.

Although poultry prices and stock plummeted in the wake of the report, USDA is now pushing for a program that would cut inspections even further and speed up production lines. When the program was tested at a poultry plant in Puerto Rico, however, the number of contaminated birds was actually greater after inspection. According to former USDA microbiologist Gerald Kuester, the level of salmonella increased from 54 percent when the birds arrived at the plant to 76 percent when they emerged.

After sitting through a briefing on the new modernization plan, Food Inspectors Union vice president Dave Carney told agency officials, “When I started, we used to throw the contaminated bird away. Then, we trimmed the contamination away. Now, we’re rinsing the contamination away. It looks like we’re going to eat contamination away.”

USDA is also anxious to extend the “streamlined” inspections to cattle, pigs, and “light fowl” — egg-laying hens that are no longer productive. Light fowl that emerged from a pilot plant were often covered with abscesses oozing yellow fluids or were bright red from bruises and internal hemorrhaging. The inspection simply did not allow enough time to detect and remove the blood.

From all reports, it seems clear that USDA and the poultry industry are deeply committed to a philosophy of “see no evil, hear no evil.” The trends are too deeply ingrained for isolated federal inspectors and plant workers to reverse through acts of professional martyrdom. The USDA stamp of approval will be worth its rubber again only if consumers join whistleblowers in denouncing inspection cutbacks and insist on tough federal standards to bring the poultry industry out of The Jungle and into the modern world.

Tags

Tom Devine

Tom Devine is legal director of the Government Accountability Project, a non-profit watchdog group based in Washington, D.C. (1989)