This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 17 No. 2, "Ruling the Roost." Find more from that issue here.

Thelma and J.C. Ross couldn’t resist the promise of full-time pay for part-time work.

A decent living is hard to come by in Oak City, North Carolina, located two hours east of Raleigh in a rural county plagued by poverty and unemployment. So when Perdue Farms began looking for farmers to grow their chickens in the mid-1970s — and promising good money for a two-hour-a-day job — the Rosses jumped at the chance.

Every few weeks, they were told, they would receive a shipment of three-week-old chickens to raise until the birds were ready for slaughter. The Rosses would pay for the construction of two large chicken houses, as well as all the equipment necessary for poultry farming. Perdue would provide the birds and feed. The couple would be paid at a rate set by Perdue.

“They said, ‘This is a joint venture; we’re supposed to work together,’” J.C. recalls. More importantly, the Perdue rep promised J.C. that he could raise the chickens without hiring any labor. “I must have asked him that 100 times. Because I didn’t want houses if I had to hire labor.”

Convinced they were getting a good deal, the Rosses took out loans from two federal agencies to build their first two chicken houses. For the first year, all went according to plan.

But the Rosses kept hearing rumors that Perdue would stop delivering three-week-old chickens to the farmers, and substitute newborn chicks. Newborns require fulltime supervision and are more vulnerable to heat, cold and rain. “We heard it through the grapevine, but they denied it every time we asked,” Thelma says.

Then one day, the word came down that the rumor was true. J.C. told a Perdue rep that he couldn’t afford to grow newborns. “His response was, ‘You would get day-old or you would get nothing,” ‘J.C. says.

“You’ve got that loan out from the Federal Land Bank. What are you going to do?” asks Thelma. So she quit her job working the midnight shift at the Carolina Enterprises toy factory, where she had worked for 17 years, to devote all her time to chicken growing. They hired labor, and refitted their chicken houses for newborns. They rented out their tobacco farm because they no longer had time to tend it. To justify the cost of hiring labor, they went further into debt to buy a third chicken house.

“We had to foot all that bill. Perdue didn’t foot one bit,” says Thelma.

Thirteen years later, Perdue officials say they don’t remember any situation like that ever occurring. Meanwhile, Thelma and J.C. Ross still farm chickens for Perdue — and earn just about minimum wage, they figure. J.C. is now 70, and he plows his monthly Social Security check right back into the poultry operation. They’re still in debt, and 55-year-old Thelma says, “I won’t live long enough to pay it off.”

The Rosses say the promise of working together with Perdue in a “joint venture” never materialized. “If you don’t do what Perdue says, you don’t get chickens,” Thelma says. “Perdue doesn’t want you to tell them anything. They give the orders.”

If she had known 13 years ago what it would be like to grow for Perdue, Thelma adds, “I’d have worked at Carolina Enterprises till I got too old that I couldn’t see.”

“Serf on Your Own Land”

It used to be that North Carolina agriculture was synonymous with tobacco. But over the past five years, tobacco has taken a back seat to poultry in the Old North State.

In 1987 North Carolina grew $582 million worth of broiler chickens and $312 million worth of turkey. And the state is not alone among its neighbors: The top six broiler-producing states are all in the South — Arkansas, Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Texas. Together they accounted for 3.5 billion of the 5.2 billion broilers grown last year. And those numbers are growing as America forswears red meat.

“The consumers’ spending habits have changed,” says Kim Decker, poultry marketing specialist for the N.C. Department of Agriculture. “They’ve tended to go to healthier foods, and most of the time poultry is a reasonably good buy.”

In North Carolina, 4,200 farmers — more than a fifth of all poultry growers in the South — raise chickens and turkeys. But these are not the independent farmers one associates with tobacco and other agricultural products. Rather, 99 percent of all broilers and 90 percent of all turkeys are grown by farmers under contracts with large poultry corporations.

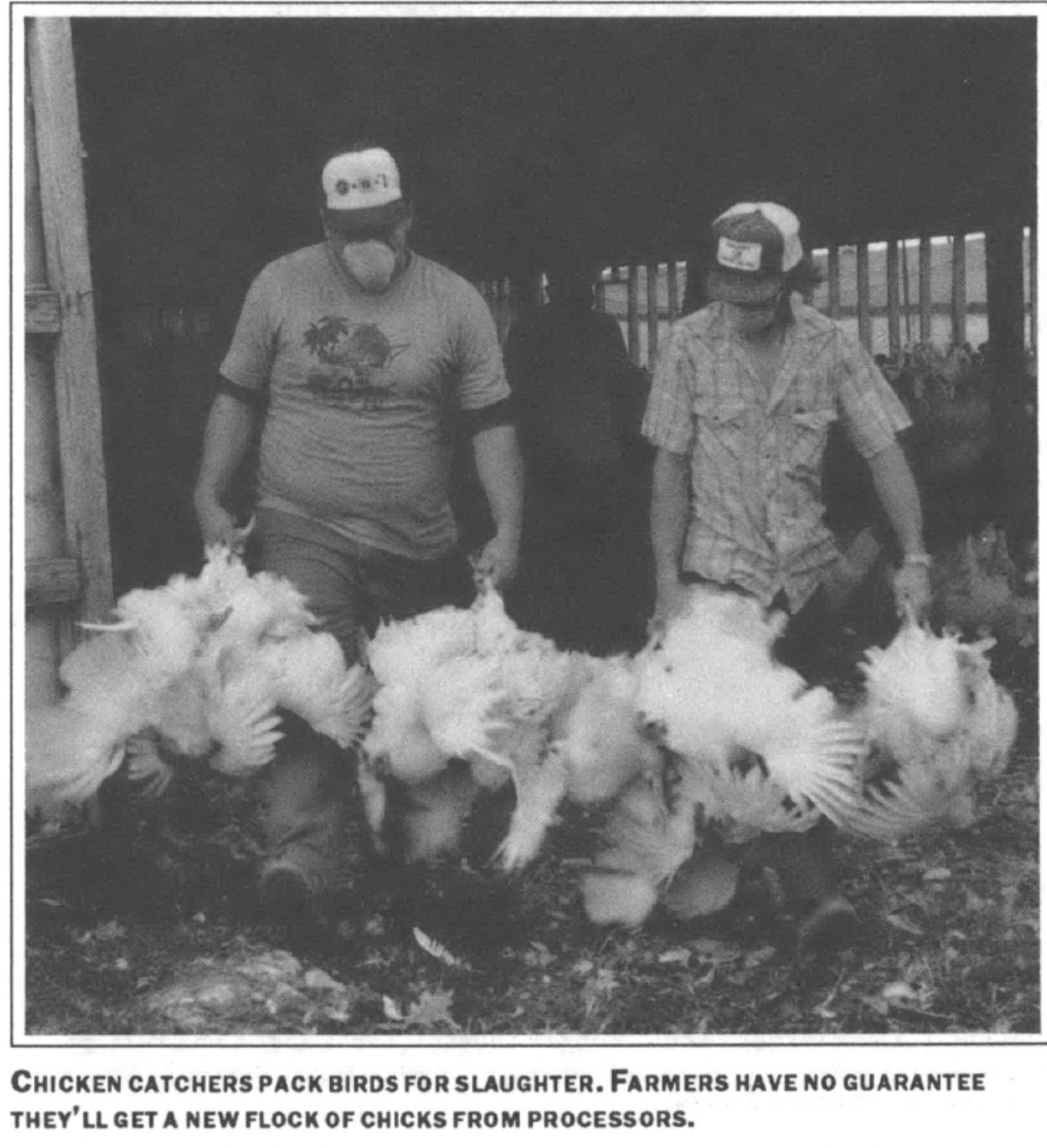

The companies — Perdue, Holly Farms, Golden Poultry, Tyson, and a few others — provide the chickens, feed, and medication. The farmers provide the houses, which can run upwards of $100,000 apiece, as well as equipment, labor, and utilities. At slaughter time, the company sends its trucks to the farm to pick up the birds; it pays the farmer based on the number and weight of the chickens, their survival rate, and the amount of feed used.

The poultry industry says this arrangement, called “contract farming,” benefits both the companies and the farmers. “We can assure our customers of a steady flow of the products they want,” says Paul Brower, vice president for communications at the Atlanta-based Golden Poultry Co. “And the farmer has a ready market for his product. He is not, then, assuming any market risk.”

Some farmers agree. “I’d rather do it than anything I’ve ever done,” says John Tucker of Pilot Mountain, North Carolina, who was forced by lung cancer to retire after 25 years in the business. The work wasn’t hard, he says, and he made “good money.”

But others paint a far different picture. They say the poultry growers — by entering into a relationship with large corporations — lose all control over their farms. “You are like a serf on your own land,” says Mary Clouse, a grower who also works for the Rural Advancement Fund (RAF), an advocacy group for small farmers based in Pittsboro, North Carolina.

Growers have no say over the quality of the chickens or the feed they receive. If they get a flock of sick birds or poor-quality feed, they must absorb the cost. The company tells them what type of equipment to buy (including experimental equipment) and when to use it. It tells them how many chickens will be delivered, how often, and on what days. Growers are expected to be on call anytime the company wants to deliver or pick up a batch of chickens.

And the growers have no say over how much money they’ll get for growing chickens. The company makes an offer — and doesn’t negotiate.

“You don’t have any bargaining power,” Clouse says. “Our choice is to take it or leave it, and that’s no choice because we can’t leave it. We have a mortgage payment due in six months.”

“The farmer pretty much works like a wage-earning worker,” says Betty Bailey, an RAF project director. But unlike wage employees, poultry growers can’t change jobs because they have often mortgaged their homes and land to borrow tens of thousands of dollars. And unlike wage employees, they don’t receive workers’ compensation, retirement benefits, health insurance, or paid vacations.

“If I was working for Hardee’s, Christ, they’d pay you if you hurt yourself,” says David Mayer, an Oak City grower. “And on the day you retire, [poultry companies] tell you, ‘Adios, amigo. You’re an independent contractor. You take care of your own self.’”

Working for Chicken Feed

Golden Poultry’s Paul Brower describes the payoff from chicken farming as “a comfortable income. Usually the broiler growers in any community are going to be the best paid in the community.”

But according to RAF, that rhetoric exceeds the reality. The organization cites 1984 state figures showing that the average broiler grower could expect to earn $1,409 per house per year before taxes. Some poultry farmers — like those growing breeder hens — could actually expect to lose money, according to the same report.

“The companies would have you believe you’re making a good income,” says David Mayer, who grows for Perdue. “But after you pay your real expenses — pay your note at the bank, pay the utility bill — I would say that you probably, per house, get $2,000 a year income.” At that rate, a farmer working 40 hours a week to tend three chicken houses would average $2.88 an hour — well below the federal minimum wage.

“What really adds insult to injury,” Mayer adds, “is when the state officials talk about, ‘Man, oh man, the prosperity of the chicken farmers is unbelievable.’”

Perdue doesn’t dispute Mayer’s $2,000 figure. But Larry Winslow, the company’s vice president for fresh poultry, calls the number “misleading” because it’s a minimum, and it doesn’t include the equity the growers build in their chicken houses. “We’ve got over 1,000 people in North Carolina that are doing it, and that number continues to grow,” he says. “At least a large portion of them consider it a good business investment.”

Bunch to Bunch

Perhaps what most frightens poultry growers is the complete lack of security contract farming offers. Almost all growers have “bunch to bunch” contracts: There’s never a guarantee that the grower will receive more than one more flock of chickens. For a farmer with a 15-year mortgage on a pair of $90,000 chicken houses, the prospect of being cut off can be terrifying.

So terrifying, in fact, that many growers are afraid to complain when they feel they’ve been mistreated, for fear they’ll lose their contracts. “If you want to keep chickens, you keep your mouth shut,” says one farmer who claims he was cutoff for complaining too much. “That’s what we learned to do.”

The poultry industry says that even without long-term contracts, competent growers can expect long-term relationships with their companies. “If they perform up to or exceeding our standards, they will get another flock,” says Golden Poultry’s Paul Brower. “If, after working with them, we find their production does not meet our standards, then after a period of time — if they refuse to upgrade their facilities and management techniques — we don’t provide flocks to them any longer.”

Many farmers say the industry is far more arbitrary than that. “The poultry companies will move into an area, they’ll get a whole lot of farmers involved,” says Betty Bailey of RAF. “As those houses get older, it’s not uncommon for them to go after new growers and abandon the older growers. The farmers are not making enough money to keep their houses upgraded.”

Larry Winslow, the Perdue vice president, says the company only drops older growers who can’t compete. “If you have a house out there, and it’s 13, 14, 15 years old, and you haven’t done anything in terms of updating the house, if you’ve skimped on your maintenance, you can reach a point where you can’t be competitive.”

Even some farmers who spend thousands on repairs and new equipment fear being dropped. Sandy Mis, for example, has only praise for Golden Poultry, the company with which she contracts to grow chickens in Goldston, North Carolina. She loves the work; it allows her to stay home while her husband sells trailer hitches on the road. And she talks about the chickens as more than a crop: “Maybe it’s the mother’s instinct in me: I like to see my birds tucked in at night. I sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to them once a week because they only live for seven weeks. I sing lullabies to them at night.”

Some day, Mis expects chicken farming to earn her a good profit, allowing her to travel with her husband after he retires. But “so far, everything we’ve made on the chickens has gone back into the farm.” And she has received no assurance that her aging chicken houses, on which she’s spent thousands of dollars in improvements, will still be acceptable after she begins making money.

“The trend is, with all companies, toward new houses,” she says. “The mental pressure of ‘are we going to get another flock?’ is enormous.”

No More Chickens

In 1968, Richard Yearick sold his three car dealerships and moved his family back to Sturgills, North Carolina, across the road from the log cabin in which he was raised. In that mountain community, just a half-mile from the Virginia state line, “about the only profitable thing was poultry.”

So Yearick approached Holly Farms to talk about growing chickens on his 150-acre farm. He says the poultry giant made him a promise: “They would continue raising chickens in this section as long as we raised the chickens to their expectations.” With that vow in mind, Yearick invested $ 175,000 to build two chicken houses and buy equipment. He later built five more houses.

Now, five times a year a company truck pulls up to Yearick’s farm carrying more than 150,000 day-old chicks. For seven weeks Yearick raises the birds — until a platoon of trucks comes to carry them off to the slaughter. His 31-year-old son Rick dropped out of a business degree program at nearby Wilkes Community College to work alongside him, hoping to take over the farm when Yearick retires.

Yearick says Holly Farms has treated him well over the years. Compared to other companies, he says, Holly Farms pays well and gives its growers periodic bonuses and raises. “A very excellent relationship,” he says.

So excellent, in fact, that Yearick didn’t worry too much last summer when the company ordered him to install “foggers”: high-pressure sprinklers that spray a fine mist when the chicken houses reach 90 degrees.

Yearick thought the foggers were unnecessary; the North Carolina mountains rarely suffer 90-degree heat, even on the August days when flatlanders swelter. But according to Yearick, the company said, “Install it or you don’t grow chickens.” So Yearick spent $8,000 on the foggers. He also spent another $12,000 on a new system to carry feed from the storage tanks to the chickens.

Then, just weeks after he invested $20,000, Yearick received the news: Holly Farms was cutting him off. He and 55 of his neighbors would continue to get baby chicks until September 1, 1989 — but then there would be no more.

Holly Farms says it could no longer afford to send its trucks across the winding mountain roads of northwestern North Carolina. “Companies like Holly Farms occasionally have to streamline operations to help us remain competitive,” says company spokesperson Ron Field. “We were reluctant to make this move, which we think was a prudent business decision.”

Field says Holly Farms tried to help the growers by giving them more than a year’s notice before the actual cut-off. “I’m sure the company never intended to say it could go on forever,” he adds.

Yearick feels Holly Farms doesn’t understand the effects of its “prudent business decision.” Before they received the cut-off notices, he says, a group of growers approached Holly Farms to make sure they would continue to get chickens after they invested in repairs and new equipment. “Holly Farms told them, ‘Go ahead,’” he says. “Some of the people, they mortgaged their homes to do their repair work.

“There are people that’s going to lose everything they own by ill advice from Holly Farms,” he says.

Yearick says he’s lucky. Though chickens account for 80 percent of his gross income, he also has investments in cable television and real estate. And he’s raising 200 or 300 head of cattle, as well as white pine for timber.

Some of his neighbors aren’t so lucky. Across the county, in the community of Fleetwood, Joe Brown has been growing chickens and cattle since he left Appalachian State University in 1963. Without chickens, he’s going to have to find another job — but he doesn’t think anyone will hire him.

“I’ve never done anything but mess with chickens and cattle,” he says. “There’s no industry around here that’s looking for a chicken shit sprayer.” Brown’s cattle won’t provide enough money for his survival.

“It’s really looking blue,” he continues. “We ain’t got nothing encouraging at all to look forward to.” He looks down, and spits tobacco on the soil of the farm that was his childhood home. “We put it in the good Lord’s hands and hope he’ll take care of us.”

Home on the Range

Losing their chickens has united Brown and the other 55 farmers cut off by Holly Farms. The Mountain Growers Association is exploring the possibility of refitting chicken houses for turkey production, but “to this date it hasn’t worked out,” says Yearick, the group’s leader. Even if it does, turkey farming would still probably mean contracting with a company.

In the state’s Piedmont region, other farmers are looking at real alternatives to contract farming. The Rural Advancement Fund and others are studying the feasibility of growing “range poultry”: chickens and turkeys raised in the sun and fresh air without hormones or antibiotics. Currently, health-conscious chicken eaters have to import frozen range birds from California.

The study, funded by the N.C. Rural Economic Development Center, will survey consumers, restaurants, supermarkets, and other potential buyers. RAF will also analyze how much it will cost farmers to raise range birds.

“This would be returning to a healthier product — the kind of thing people need to be willing to pay a little more money than they pay for the mass-produced product,” says RAF’s Betty Bailey. “It would model a real living alternative and improve quality of food and quality of life for both farmers and consumers.

“It could return farmers back to being their own boss, to being the innovative, constructive farm operators they have been in the past, to being able to live in dignity and with a decent income themselves.”

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)