The Death Squads in Houston

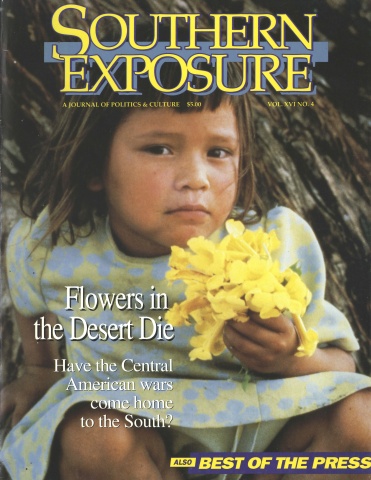

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 16 No. 4, "Flowers in the Desert Die." Find more from that issue here.

The young Salvadoran man was frantic. He had come to feel safe in Houston by the spring of 1987. But he was very worried about his mother, his sister, and his uncle in San Salvador.

Last March, he received a call from his mother. Members of a death squad had come to her home demanding to see his uncle. The uncle was away from home at the time. But the two death squad members were not deterred.

“Produce the man the next time we return, or we will kill you and your daughter,” they told the mother. “Moreover, we are watching your son in Houston who works with a solidarity group as well. Neither you nor your daughter or son will live if you don’t produce him for us.”

With the coming to power of the Reagan administration in 1981, the political destinies of El Salvador and the United States became more closely intertwined than ever before. The most apparent impact of that relationship is visible in the swelling population of illegal Salvadoran immigrants in the South. It was manifest, as well, in the controversy over the sanctuary movement which culminated last year in the conviction of 11 citizens who sheltered Salvadoran refugees entering the country illegally.

But beneath those visible demographic and legal changes, the close relationship also spawned a quiet outbreak of low intensity political warfare launched by the Reagan administration-supported Salvadoran right wing against political dissenters inside the United States.

Former FBI employees and other sources now indicate that the Salvadoran death squads have been operating in Houston and other Southern cities for several years. Financed in part by a handful of wealthy Salvadoran exiles in Southern Florida and California, highly secret, mobile teams of former Salvadoran soldiers and police are suspected in a rash of death threats, break-ins, and abductions stretching from Miami and Houston to the rest of the nation.

Sources familiar with the death squads also indicate that the FBI not only gave the Salvadoran military information on Salvadoran opponents being deported back to El Salvador, but also furnished information that may have helped the death squads target American citizens opposed to Reagan administration policies in El Salvador.

Exporting Civil War

The U.S. operation of the death squads can be traced back to 1979, when five Salvadoran groups fighting the military and the privately organized death squads united under the umbrella of the FMLN. The Carter administration responded by installing a Christian Democratic ruling junta and initiating a series of economic and agricultural reforms to moderate the intolerable financial gap between the country’s long-standing oligarchy and its impoverished land-based peasantry.

It was a solution that satisfied no one.

The Salvadoran left saw the move as a veiled initiative to sugarcoat U.S. support for an iron-fisted military government with superficial reforms.

The country’s right wing saw the move as a diabolical plot by the CIA and State Department to impose instant socialism on El Salvador and, in the process, to wrest power from the handful of wealthy Salvadorans who had traditionally controlled the economy.

The subsequent reaction of both factions led to the export of the Salvadoran civil war into the U.S.

A tiny country of little economic or strategic importance to the U.S., El Salvador nevertheless became an obsession for William Casey, the incoming director of the Central Intelligence Agency in the Reagan administration. To Casey, El Salvador was a “textbook” conflict with the Soviet Union, and the most important symbol of the life-and-death battle between democracy and Marxism-Leninism.

In his recent book Veil, journalist Bob Woodward reported that information on Soviet military supplies being shipped to El Salvador painted “a paper picture of Communist global conspiracy that conformed with Casey’s predisposition. The hands of the Soviet Union, Cuba, North Vietnam, Eastern Europe, and Nicaragua were all involved in directing a supply route aimed at El Salvador. The case was almost as tight as a drum.”

Based on those findings, President Reagan signed a secret order in early March 1981 to provide propaganda and political and military support to the Christian Democrats and the armed forces of El Salvador.

The next month, apparently following the administration’s new policy, the FBI began a massive, five-year investigation of U.S. groups opposed to the Salvadoran regime — most notably the newly born Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES).

To aid the investigation, the FBI established secret channels with the Salvadoran National Guard to exchange information on suspected communists who were heading north — either through the emerging sanctuary movement, or among the thousands of refugees crossing the Rio Grande to flee the exploding violence in their own country.

The concept behind the Texas-based CISPES investigation — which was part of a larger probe of Salvadoran terrorism — was to squeeze political opponents both in El Salvador and in the U.S.

As part of the arrangement, the FBI agreed to furnish the National Guard with information on asylum seekers who were being deported to El Salvador — and on CISPES and other activist groups in the United States.

Database and Death Threats

In April 1981, the FBI sent a new FBI contract employee named Frank Varelli to El Salvador to establish a secret channel with the National Guard. Varelli, a naturalized American who had left El Salvador the previous year, was the perfect person for the job. His father, Agustin Martinez Varela, had been director of the Salvadoran Military Training Academy, director of the Salvadoran National Police, and the Minister of the Interior.

Varelli contacted Eugenio Vides Casanova, at the time director of the National Guard, who had been a student of his father at the military academy. Casanova agreed to cooperate with the FBI in a joint secret investigation aimed at undermining the left-wing opposition in El Salvador and monitoring the Salvadoran left’s sources of political and financial support in North America.

When Varelli returned from El Salvador, he headed for the Dallas office of the FBI — headquarters for the Bureau’s massive investigation of CISPES. He brought with him an intelligence windfall. Among the prizes was a database containing the names of hundreds of suspected and known left-wing opponents. It was compiled by Ansesal, a Salvadoran presidential police force, with the help of right-wing associates of Roberto D’Aubuisson, the alleged leader of the Salvadoran death squads.

Varelli also brought with him the text of a recent strategy speech by Roman Mayorga Quiroz, an official of the FDR, political allies of the armed Salvadoran opposition. The strategy of the FDR, Varelli showed the FBI, was to set up 180 solidarity groups in the U.S. to pressure the Reagan administration to abandon its policies of military aid and intervention.

Finally, Varelli brought one more piece of intelligence to the Bureau. He learned, while in El Salvador, that a small group of wealthy, highly influential Salvadoran leaders was planning to establish its own private intelligence gathering operation in the U.S. The group planned to monitor Salvadoran opponents in the States as well as to keep tabs on their North American political allies.

In other words, the chief bureau charged with enforcing federal law knew in advance that a powerful private group in a foreign country was planning to spy on American citizens inside the U.S. — and it decided to cooperate with the foreign spies.

Before long, the death squads were operating across the U.S. Death threats became commonplace. Since 1984, more than 100 break-ins have occurred at the homes and offices of Central American activists. While none of the burglaries has been solved, activists suspect the involvement of right-wing Central Americans in a substantial number of them.

“To Marta Alicia, who was tortured and left for dead, and her terrorist comrades. For being a traitor to the country, you will die, together with your comrades. You survived in El Salvador. Here, with us, you will not. Do not speak in public.”

The letter, which was delivered anonymously through a mail slot in the door of the Los Angeles office of CISPES in early July 1987, went on to list the names of 18 other members of the organization. It concluded: “No one will be saved. Death. Death. Flowers in the desert die.”

The last phrase in the letter is particularly ominous. When death squads in El Salvador marked a political opponent, according to one source familiar with the operations of the squads, “They would leave flowers by the door and the next day the person would see them and know what it meant and many would leave the next day.”

Over the next year, similar threats were received at refugee assistance centers, as well as CISPES offices, in Minneapolis, Washington, Boston, and Los Angeles.

By the time the FBI investigation of CISPES was a year old, the private Salvadoran network in the U.S. was operating at full force. Bankrolled by a handful of wealthy Salvadoran exiles in South Florida and California, the operation made its headquarters in the South. It boasted a large Wang computer in Houston, which it used to surveil and monitor leftist Salvadorans who came to the U.S. to speak and meet with support groups — university professors, teachers, trade unionists, and officials of the FDR. The clandestine Salvadoran network also monitored a number of meetings of CISPES and other U.S. political groups involved in Central American issues.

For at least three years, the private Salvadoran group routinely provided information to the FBI. The Salvadorans felt that the Bureau, unlike the CIA or State Department, understood the real problems of the country and was not about to sell it out to what they saw as a socialist government headed by Jose Napoleon Duarte and the Christian Democrats.

The Salvadoran network also provided a fertile source for FBI recruits. Among them, Varelli alleged, were two Salvadoran brothers who had been convicted of counterfeiting and gun smuggling in El Salvador. The brothers were identified in teletypes from the Miami FBI office as intelligence sources in the CISPES probe. Among other activities, the men infiltrated meetings at Florida State University in Tallahassee, which hosted left-leaning Salvadoran university officials.

In an interview last year, Varelli said the families who organized the private Salvadoran corps, which includes a number of former Salvadoran military and police personnel, are “totally frustrated” because “they can’t get their message into newspapers and they can’t buy air time on TV” to counter administration propaganda about the “so-called democracy” in El Salvador.

Noting the emergence in the U.S. of another death squad named the Domingo Monterrosa Command, Varelli warned of the possibility of guerrilla war in the U.S. “The death squad activity here won’t be easy to stop,” he said.

He speculated that the U.S .-based Salvadoran operation involved small cadres of from 30 to 100 Salvadorans in cities with large Salvadoran refugee populations, including Dallas, Houston, Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.

“They operate out of cities where they can easily blend in,” he said, noting that the highly secret teams operate in units of two or three to be able to move about inconspicuously.

Varelli explained that the Salvadoran families who organized the terrorist squads were thoroughly frustrated with the Reagan administration for its support of Duarte. “They believe the CIA fixed the voting machines to assure Duarte’s election,” he said. “As a result, they decided to hit where it will hurt — here in America.”

Varelli, who was one of two men in the FBI’S Dallas office who coordinated the five-year probe of CISPES, said he met with several members of the Salvadoran network in 1985. “It was amazing,” he concluded. “They knew as much about CISPES as the FBI did.”

“None of Our Business”

The relationship between the U.S.- based Salvadoran operation and the FBI cooled somewhat in 1983 following an assassination attempt on a Miami-based official of the Duarte regime. The Bureau conducted a preliminary and, critics say, deliberately superficial investigation of right-wing Salvadoran elements in South Florida, and distanced itself from the clandestine group.

But the relationship between the FBI and the Salvadoran military continued unabated. And as always, much of the operation was based in the South.

In 1983, for example, Varelli traveled to Houston to arrange for the FBI to forward the names of Salvadoran deportees to the National Guard. He persuaded an employee of TACA, the Salvadoran airline, to provide passenger manifests to the Houston FBI office which, in turn, forwarded the names to the National Guard. The same employee subsequently arranged a job with TACA for an FBI agent who also had access to the passenger manifests.

Asked whether the deportees were killed or “disappeared” after they arrived in El Salvador, Varelli said, “We in the FBI actively did not want to know what happened to them. Our only concern was to get the information to the Guard. After that, it was none of our business.”

Varelli added that the FBI also surreptitiously paid a Salvadoran Consulate official to provide names and passport information on American activists who applied for visas to travel to El Salvador. The information enabled the FBI to have the activists monitored in El Salvador.

In early July 1987, 23-year-old Yanira Corea, a volunteer at the CISPES chapter in Los Angeles, was driving to the airport with her three-year-old son when another car forced her onto the shoulder of the road. Two men jumped out and approached her car. One tried to pull her out. The other took a book which contained a small photo of her son. Corea escaped, but her son was so disturbed he did not speak for three days.

Two weeks later, she received a letter with her son’s photo. The letter bore the phrase: “Flowers in the desert die.”

The following week, when Corea left the office of the medical firm where she worked, three men approached her and forced her into a waiting van. Two of the men, she said later, had Salvadoran accents. The third sounded like a Nicaraguan.

“They accused me of being a communist and a member of the FMLN. I knew they were death squad people. They asked about my brother. They wanted names of people who they said raise money for the FMLN. They wanted information about other members of CISPES.”

The men drove Corea around Los Angeles for six hours, during which time they carved an E and an M—the initials for Escuadron de la Muerte — into the palms of her hands. They burned her with cigarettes. And they raped her with a stick. (The injuries were later confirmed by a doctor who treated her.)

Nor was that the end of her ordeal. Shortly after the attack, Corea moved into a new apartment with her mother and son. Two days after the move, she began to receive more death threats over her new, unlisted telephone.

Five months later, when she was planning to travel to New York for a speaking engagement, she received a copy of a flier with a handwritten Spanish phrase: “Do you know where your son is? “ A line drawing on the note showed the torso of a decapitated child. A crudely drawn head lay nearby.

On one level, the death threats, break-ins, and abductions have generated complaints about the indifference of the FBI and other law enforcement agencies. Following the abductions last year of Corea and another CISPES volunteer, Mark Rosenbaum of the American Civil Liberties Union said: “Neither the FBI nor the Los Angeles police have dug into the Central American right wing. There is lots of evidence of a very political character that can’t be explained any other way. But the police and the FBI pretend it doesn’t exist.” A spokesman for the FBI responded that the Bureau can’t investigate an entire group like right-wing Salvadorans without violating that group’s civil liberties.

On another level, however, the clandestine Salvadoran operation has raised ominous fears about violations of the American political process. U.S. Representative Don Edwards (D-California), who last year held hearings on the break-ins, has expressed concern about the Salvadoran conflict being waged on American soil.

“From the outset, I have felt the break-ins may be the work of agents of one or more Central American governments representing the ruling classes in those countries,” Edwards wrote last year. “Another possibility is that the break-ins are the work of right-wing groups who support the contras and U.S. policy in Central America.”

Citing the activities of agents of the Shah of Iran and former Philippine leader Ferdinand Marcos, Edwards added: “We know that in the past, violent governments have sent their agents to the U.S. to harass and intimidate their opponents here. . . . Is history repeating itself?”

Tags

Ross Gelbspan

Ross Gelbspan is a reporter for The Boston Globe. (1988)