Questions About Tourism

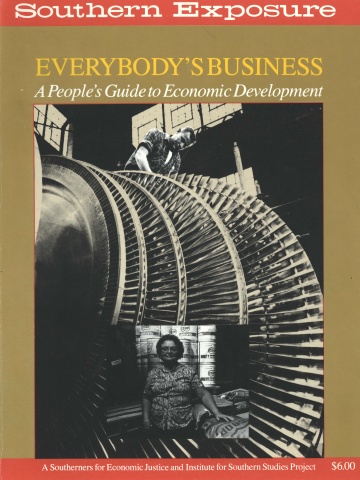

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 14 No. 5/6, "Everybody's Business." Find more from that issue here.

"Virginia is for lovers." "Stay and see Georgia." "Visit wild, wonderful West Virginia."

Welcome to the latest episode in the Southern states' scramble for dollars and jobs: tourism is the new name of the game. Many state development officials now court hotel and resort developers with the same ardor they accord manufacturers. Tourism already ranks among the top growth industries in several Southern states; it is a powerful economic force in many areas along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, in the Appalachian mountains, and in urban resort centers like Orlando. The total dollars generated by travel and tourism ranks it among the top four business activities in a majority of Southern states.

A clean, safe industry, an influx of tourist and investment dollars, and a bonanza of jobs — these are the benefits promised local communities by supporters of tourism. But for people who have no business to own or capital to invest — that is, for most poor and working-class Southerners — the benefits of tourism are more mixed. Tourism involves more than the simple addition of a few new businesses and jobs to the economic mix of a local community. It involves an entire way of life, which tends to transform the existing patterns of land ownership, indigenous culture, political relationships, and economic base. Some potential problem areas that individuals and community groups facing tourist growth should consider are:

Land Ownership Tourism tends to send land values skyrocketing, and property taxes follow accordingly. Unable to pay their taxes, rural people whose primary resource for generations has been their land can lose it in a matter of months. Especially along waterfronts, the sale of property can cut off a community's access to traditional fishing (crabbing, etc.) areas, which represent important sources of food and income. Among the tactics community groups have used to combat these problems are development of low-interest loan funds (to assist individuals with tax payments), monitoring of land sales, promotion of leasing under specified terms rather than outright sale, land trusts (in which property is jointly owned), and community education about the economic and cultural value of land.

Culture People with a distinct cultural heritage, such as blacks who live on the coastal islands of South Carolina and Georgia, typically find their ways of life eradicated by the growth of tourism. This occurs through erosion of the traditional economic base (for example, fishing and agriculture), changes in the class and racial mix of the community, and the deliberate creation of an ambience of leisure, ease, and entertainment. Promotional literature about these "island paradises" adds the final touch by depicting the communities as wealthy white playgrounds, and by rewriting their history to eliminate blacks, slavery, and other intrusions of reality. Community groups have combatted these trends through educational projects, cultural festivals, museums, oral histories, and other activities designed to protect and celebrate their heritage.

My Turn: Closer to Home

Daufuskie's blacks are now being treated pretty much the same way as Hilton Head blacks were treated. We have given up on trying to protect the shrimp and the crab because we have become the new endangered species. We are just one example of many throughout the world. Developers just come in and roll over whoever is there, move them out or roll over them and change their culture, change their way of life, destroy the environment, and therefore the culture has to be changed.

— Emory Campbell

South Carolina

Jobs There is little doubt that tourism tends to create a large pool of new jobs in a community; however, the quality of those jobs is another matter. Maid, cook, waitress, gardener, sales clerk — these are the occupations of a tourist economy. They are jobs at the bottom of the service sector, where pay is low and benefits are few. Due to the seasonal nature of tourism, these jobs may also be temporary, which reduces their annual pay even further. Challenging the quality of tourist-related jobs is a formidable task. Unionization, job training, and organized pressure on employers to hire from the local population for higher-level positions have all been tried, but to date the success rate has been low.

Politics Insofar as tourism transforms the economic base and social mix of a community, it also affects local politics. Developers and businesses dependent on tourism become powerful political forces. In locations where retirement and second-home development has flourished, the make-up of the voting population can shift dramatically — with consequences for elections and political control. Conflicts have flared between business interests and community groups over the location of water and sewer projects, the role of local police, and the allocation of revenues from taxes. Lifelong residents and more recent arrivals, especially retirees, have struggled over the amount of funds allocated to public institutions like schools.

In areas where tourism has already taken over the economy, community groups have found it nearly impossible to rectify these problems. Their experiences offer a grim but important warning to those who live in areas where tourism is just beginning. Community organizations must be prepared to address these problems (or stop tourism altogether) if they seek economic development that truly benefits poor and working-class people.

Total Dollars Spent for All Travel & Tourism 1984

State Billions

Alabama $ 1.62

Arkansas 1.82

Florida 17.65

Georgia 4.85

Kentucky 2.22

Louisiana 3.73

Mississippi 1.25

North Carolina 5.25

South Carolina 3.02

Tennessee 3.33

Texas 14.98

Virginia 4.42

West Virginia 1.27

Total South $ 65.40

Total U.S. $222.96

Source: U.S. Data Center on Travel & Tourism

Tags

Barbara Ellen Smith

Barbara Ellen Smith is research director for the Southeast Women's Employment Coalition. (1986)

Barbara Ellen Smith lives in West Virginia and was a participant in the black lung movement. (1984)