Sick Chickens

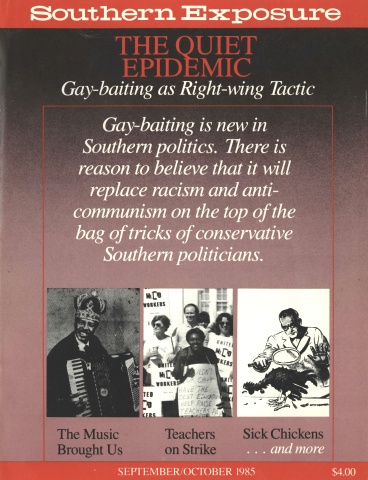

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 13 No. 5, "The Quiet Epidemic: Gay-baiting as Right-wing Tactic." Find more from that issue here.

Clara Holder, an east Texas poultry worker, wrote a letter on June 26, 1953, to Patrick Gorman, the secretary-treasurer of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of America. "I was told to contact your office to secure help in organizing a much needed plant," she wrote. "The majority of the workers are eager to organize, if only they had some advice from a bonafide labor union. Would you kindly inform me if your organization can help us."

Clara Holder's brief letter sparked a tortuous organizing campaign in Center, Texas, that stirred racial and class tensions, triggered a national boycott, and persuaded the union to launch a successful drive to reform the entire U.S. poultry industry.

Poultry was introduced into Texas by both the Spanish and Anglo-American colonists. But it was a nondescript industry producing primarily for home consumption and local markets until the mid-1920s, when outlets for commercial marketing opened up with the establishment of poultry packing plants in Fort Worth, Taylor, and a few other towns. During the wartime boom of the 1940s, when poultry was not subject to meat rationing, the industry entered a new phase with the widespread commercial production of broilers and young fryers. The first noteworthy production was around Gonzales in south Texas. In the Lone Star State by the mid-1950s, the industry had spread to Shelby and nearby east Texas counties.

Aside from the bloody battles between the so-called Regulators and Moderators in the 1840s, Shelby County, deep in the piney woods, had been noted primarily for its lumbering. During the 1940s business leaders in the county seat of Center organized the Center Development Foundation to attract industry. They offered the usual inducements of land, buildings, and/or low taxes, accompanied by a typical pool of unskilled, native, black, and white laborers who were abandoning their marginal cotton farms. The county and the school district also granted tax concessions to several firms. By 1954 Shelby ranked a close second to Gonzales County in chickens sold in Texas with 8,227,247.

Like most small Southern towns, those in east Texas had long regarded unions as radical threats to God, home, and country. Lumber baron John Henry Kirby probably summarized the region's feelings in 1911 when he referred to conservative, AFL-type unionism as "a greater menace to Christian civilization than the anarchists, Black Hand, Molly Maguires, Mafia, Ku Klux Klan, and Night Riders."

Shelby County consistently supported east Texas's long-time congressman, Martin Dies (1932-44 and 1952-58), the labor-baiting chair of s the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1941 Dies observed that the CIO was infested with 50,000 Communists who were fanatical devotees of Hitler and Stalin, and that 90 percent of all strikes could be stopped if the CIO were forced to expel these alien traitors.

Workers in Center's poultry processing plants were paid the minimum wage of 75 cents an hour in 1953. Many apparently labored under highly unsanitary conditions, 10 or 11 hours a day on their feet, with no overtime pay — in between times of no work at all. The work was unimaginably grueling. One of the town's jewelers, Bernard Hooks, was appalled by the condition of the laborers' hands. They were so bruised and swollen, with fingernails often turned inside out, that Hooks frequently had difficulty fitting them with rings. Several workers attested that they had to become accustomed to painful fingers, swollen hands, and lost fingernails; no one was allowed to switch to a different plant job in order to rest his or her hands. The plants had no grievance procedures, seniority plans, or paid holidays.

The first few weeks of the organizing effort were conducted under the cloak of secrecy. After receiving Clara Holder's letter, Patrick Gorman forwarded the matter to the union's southwestern district vice-president Sam Twedell in Dallas. Twedell rapidly contacted Holder, asking her to arrange an opportunity for him to discuss unionization with about 10 of her fellow poultry workers. Twedell advised Holder to "please keep it [the proposed meeting] confidential as we would not want the employers to know anything about it until after we had the people organized."

The first meeting was held after working hours in the K.B. Cafe in Center on July 8, 1953. In the weeks that followed, the organizers easily obtained the number of names needed to call a union election. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) scheduled the union representation election for September 15 at the Denison Poultry and Egg Company. Another election was set for the employees of Eastex Company, a second poultry concern in Center, for November 5.

The local business community, a tightly knit group that ran the town, was stunned at the announcement of a union election in the city's two major plants. They launched a drive to discourage pro-union votes by the poultry workers, relying on social pressure and argumentation. A petition opposing the union was circulated among the city's business leaders which most owners signed. At least a half dozen businessmen — notably the jeweler Bernard Hooks, grocery store owner Laurie Hegler, and Weldon Sanders, a Texaco service station operator — refused to countenance the anti-union drive. For his dissent, Sanders was accused by his peers of "working for the Union and all the things that go with it" and suffered a loss in his trade.

Five days before the Denison election, the 182-person Center Development Foundation (CDF) purchased a full-page ad in the local newspaper, the Center Champion. Signed by the six directors of the CDF, the open letter declared, "We believe that Center's unusual industrial growth is partially due to the fact the Center was known as a non-union town where there has been no labor violence or strife." The ad reminded workers of the allegedly tremendous monetary sacrifices of foundation members in bringing industry to Shelby County. The foundation praised the "harmonious" relationship between management and worker and confided that "the employers tell us that you employees have made them the best and most loyal workers they have ever had." The attack on unionism concluded with a plea: "Let's all work together to make Center a better place in which to live and work rather than a town divided and torn by Strife."

While business leaders worked to sway the opinion of county residents against unionism, the plant management sought to convince the poultry workers that they neither wanted nor needed the Meat Cutters. Prior to the NLRB election, the Denison Poultry Company presented each employee with a two-page letter. The owners argued that they paid all they could afford in wages and that they already (and voluntarily) financed an insurance program and Christmas bonuses for the workers. The company claimed it was competing with poultry processors all over the nation and that unionization would cost them customers. The letter asserted that the union had to accept whatever the company offered or go on strike, and it attacked the "union method of violence, strikes, lost time and turmoil."

"You must decide," said the letter, "whether the union is making false promises to get you to pay dues." The workers also received a mimeographed statement cautioning them not to be influenced by threats that they would lose their jobs if they refused to join the union. In condemning the alleged union threats, however, the company issued its own prediction of future reprisals. "When the election is over," the statement read, "we [the company] shall retain in our payrolls all who have rendered faithful and efficient service." The Denison Poultry employees also received a letter from a group calling itself the "Loyal Employees Committee," closely echoing the arguments of the company's two letters.

Sam Twedell retaliated in kind. One of his handbills pointed out that the six directors of the Center Development Foundation were bankers, car agency owners, and one lumberman. "They don't do your kind of work or live in your kind of homes or take your kind of vacations," the circular claimed. "Would these men and their wives work in the plant for a lousy 75- per hour? THEY ARE AFRAID THAT IF YOU GET HIGHER WAGES THEY WILL HAVE TO PAY HIGHER WAGES TO THE PEOPLE WHO SLAVE FOR THEM."

Despite social pressures, company hostility, and the pleadings of "loyal" employees, both Denison and Eastex Poultry Company workers selected the Amalgamated Meat Cutters to be their collective bargaining representative. At the Denison plant, where all the workers were white, the vote was 81 to 55 in favor of the union. The election held later at the Eastex Plant approached landslide proportions. Eastex workers, 75 or 80 percent of whom were black, cast 118 votes for the union and nine against.

During the seven months following the election the organizers and officers of the Meat Cutters met repeatedly with the company owners. The labor representatives asked for union recognition, higher wages, and working conditions on a par with those in union-organized poultry plants in other regions of the country. The union even enlisted the aid of big business. One of Armour's industrial relations directors wrote Ray Clymer, owner of Denison Poultry, that Armour enjoyed "extremely harmonious relations with unions" and that the Meat Cutters were familiar with the limitations of the poultry business. But the Texas companies never firmly committed themselves to any of the union proposals. In an April 1954 letter to Patrick Gorman, Twedell summed up the negotiations thus far: "We have been meeting with the employers continuously since that time, and they would make concessions and then withdraw them at the very next conference. They would schedule meetings with us [and] then at the last minute cancel them."

Union organizer Jim Gilker drew the conclusion that the owners were not bargaining in good faith, which federal law required. He felt that the companies were determined to conduct a long fight against union recognition and wage increases. Gilker reported to Gorman that Ray Clymer "does not take the position that he can't pay more money, but states very bluntly that he won't."

By March 1954, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters had become weary and skeptical of the negotiations with the companies. They were convinced that a strike would be not only costly but also futile in an area that would quickly supply strike-breakers for the unskilled jobs in the poultry plants. Secretary-Treasurer Gorman and vice-president Twedell leaned toward economic action. As early as January Twedell had written Gorman, "We [will] put the 'squeeze' on this poultry processor in every way that we possibly can and that can be done, not by striking, but by taking away some of their large customers." Negotiations were thus subordinated to the national boycott as the means of forcing a settlement.

According to the contracts which existed between Meat Cutter locals and their retail employers across the nation, the latter could not legally sell products which had been placed on the unfair list of the union. After providing the required notice to the Center poultry companies, union president Earl Jimerson issued a proclamation declaring that "Denison Poultry Company of Center, Texas is UNFAIR to Amalgamated Meat Cutters of North America, AFL." Once this formality was out of the way, letters were sent to companies distributing Denison products requesting that they comply with the terms of their contracts and desist from handling the products of the unfair firm.

The Lucky Stores, Inc., a large San Francisco food chain, provide a typical example of compliance with the boycott directive. Upon receiving advanced word of the pending unfair decree, the company contacted Denison Poultry owner Ray Clymer to request that he immediately come to terms with the union or Lucky Stores would be forced to stop buying from his firm. Clymer replied that he had been bargaining in "absolute good faith" and recommended that Lucky Stores consult legal advice before participating in the proposed boycott. Lucky Stores announced early in April of 1954 that they would no longer purchase the products of Denison Poultry Company.

The boycott also was carried out by the local Meat Cutters unions. On March 29, 1954, president Jimerson sent letters to all locals in areas where Denison products were sold. The locals were told to wire Clymer to inform him that they could not handle a product on the union's unfair list. The locals were further directed to dissuade outlets in their areas from selling Denison's products. In California, a state that sold a great deal of Denison goods, the Western Federation of Butcher Workmen and the Meat Cutters conducted an extensive and successful campaign to ban the products of the unfair company.

Ray Clymer evidently anticipated problems in marketing his merchandise and decided to speed up his production in order to get as far ahead as possible should the boycott become completely effective. The normal chain speed on the production line in the plant was between 37 and 42 chickens per minute. By April 5 the rate had been increased to 66 chickens per minute. According to Twedell, it was not unusual for women to pass out from sheer exhaustion during the course of the day's work.

Without consulting any national union official or organizer, every union member at the Denison plant bolted off the job on the evening of April 5. Union members at Eastex initiated a walkout and were followed by all other employees of the company. Both plants were temporarily shut down by the wildcat strikes, but the companies soon resumed operations, as the Meat Cutters union feared they would, by tapping the area's unskilled labor supply.

After Twedell observed firsthand the conditions that had touched off the strike, he persuaded the union to support it. He wrote Gorman that "these people are 'the salt of the earth' and we must do everything within our limits to see that they get a square deal." Soon the threat of violence hung over the town, as picketers tangled with reckless drivers, county deputies, state highway patrolmen, and perhaps Texas Rangers.

In addition, a wave of racism engulfed the strike. As in most east Texas towns, the white citizens of Center were angered by the May 1, 1954, school desegregation decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. Thus, while white strikers seem to have been regarded as curiosities, black picketers were deeply resented. Just after the Eastex strike began, Twedell claimed that he was summoned to the county district attorney's office. There, in the presence of the sheriff, Twedell said he was ordered to "Get those goddamn Niggers off the picket line or some of them are gonna get killed." Twedell refused.

KDET radio, a strongly anti-union station, exploited the town's racist attitudes as an angle of attack on the union. On May 20 Twedell sent telegrams to the FBI and the Federal Communications Commission concerning a KDET broadcast which "openly advocated violence, as a result of Supreme Court decision . . . and other racial problems, if Negro pickets were not removed from the picket lines." Station manager Tom Foster explained that his announcer had merely stated that "Twedell himself was advocating trouble by ordering Negro and white pickets to walk the picket line together. Hancock [the announcer] said that may be common practice in Chicago [home of the union's international headquarters], but we are not ready for that here." Twedell began walking the line with the black picketers.

On May 9 organizer Allen Williams had prophetically reported to Twedell that "we are sitting on a keg of dynamite here. . . . I honestly think our lives are in danger. . . . These bastards will stop with nothing, including murder, if they think there is half a chance to get away with it." On the night of July 23 a time bomb explosion destroyed Williams's Ford. A fire which resulted as an after-effect of the detonation completely leveled two cabins of the tourist court where Williams was living and did extensive damage to two other buildings. Fortunately, Williams had stayed out later than usual on the night of the bombing and thus escaped injury. The would-be assassins were never apprehended and, according to his reports in the next few weeks, Williams held some doubts that law enforcement officers seriously sought to find them. Remarking on the openly anti-union sentiments of a majority of the members of a grand jury investigating the bombing, Williams jokingly explained that he felt some fear of being indicted for the crime himself. A second bombing occurred near Center's black neighborhood on August 12.

Neither of the two banks, whose presidents were directors of the Center Development Foundation, extended credit to their fellow townfolk on strike. But the Meat Cutters paid regular benefits through the duration of the conflict and also conducted a highly successful nationwide clothing drive for the strikers. So much clothing was received from the locals that it actually became necessary for president Jimerson to ask members to halt the donations.

Though the union neither expected nor won the support of Center's business and political leadership, it did a surprisingly good job of securing the confidence of the area's citizenry. Allen Williams believed that the union had 85 percent of the population on its side, though this hardly seems likely considering the historical image of unions in the area or the fervid racism aroused by the strike.

Both Williams and Twedell attributed a great portion of the popular support to the union's own radio program. Each Saturday afternoon the Meat Cutters purchased time on a local radio station, during which a union representative would explain various facets of the union's side of the controversy. One of these programs early in May 1954 included an explanation of the tax structure in Shelby County. The union revealed that the Eastex Poultry Plant, which had been publicly valued by its owner at $500,000, was listed on county and state tax books as worth only $5,000. Its combined county and state tax bill for 1953 had been $76. The Denison building, according to the labor broadcast, was valued on tax rolls at $1,160 and was taxed only $25 in 1953.

These disclosures embarrassed the business community and aroused the populace. Twedell repeated his charges, with 500 people looking on, before a dramatic evening session of the city council. Mayor O.H. Polley defended the low taxes as necessary inducements for industry. Union leaders then held a pep rally, and the antagonistic local newspaper, the Champion, admitted that they "were soundly cheered by a large portion of the audience." Twedell recorded that the expose "caused quite a furor and I don't believe there has been as much excitement in Shelby County since the Civil War."

The strike in Shelby County and even the Denison and Eastex boycotts were soon overshadowed by another major thrust in the union's campaign against the Center poultry firms. As early as February 1954, organizer Jim Gilker reported to Patrick Gorman:

Our ace with Denison is that they don't have Federal Poultry inspection. . . . This means that there is no doctor on the line checking the birds. . . . At the present time the inspectors are condemning a large number of birds because of "Air Sac disease" in the inspected plants. At the Denison plants these birds are packed and shipped out.

Since the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, it has been illegal to ship beef, veal, pork, lamb, or other red meat products in interstate commerce unless they have been slaughtered under sanitary conditions and inspected by government veterinarians. Many states also adopted compulsory meat-inspection laws. When these laws were being passed, however, the poultry business was still small and was not included in the provisions. By the mid-1950s poultry was a major item in the food market, but the U.S. government inspection service that was available until 1958 was voluntary and had to be paid for by the poultry processors. Only conscientious companies had government inspectors on duty, and the companies could transfer the inspectors if they did not like their work. In some companies there was a tradition of "close relations" between inspector and plant. Marginal plants as well as the unscrupulous and unsanitary companies, the ones most in need of inspection, shipped the poultry uninspected. Less than one-fourth of the poultry marketed in the U.S. in the mid-1950s had been subjected to federal inspection. Neither Denison nor Eastex hired inspectors, though Eastex claimed it hired a "resident sanitarian" in the spring of 1953.

Eastex owner Joe Fechtel told a radio audience that the union offered him a contract in lieu of exposing the diseased poultry he was processing (which he denied was happening). Pat Gorman, after receiving the first affidavits on the diseased chickens, wrote Sam Twedell that the Amalgamated would "blast the hell out of the poultry industry if the Denison and Eastex strike isn't settled."

In April 1954 Sam Twedell began forwarding affidavits depicting gory and unsanitary conditions in the poultry plants to secretary-treasurer Gorman. One Center poultry worker testified:

My job was to pull feathers. . . . When the chickens reached me, most of the feathers were off the bodies and I could see the skin of the birds very clearly. It is quite often that thousands of chickens would pass on the line with sores on their bodies. Thousands of them would have large swellings as large as a chicken egg on their bodies. These swellings were filled with a yellowish pus, and the odor was very strong. Others would have red spots all over their bodies that looked like smallpox.

An affidavit from another worker declared:

When I was killing chickens I have cut the throats of many chickens that were already dead and stiff. . . . The first time I saw these kind of chickens come along, I did not cut their throats, but [my] supervisors came and told me to cut their throats and let them go through with the good ones. . . . When on the killing job, I would also kill chickens that would be sick and have long, thick and stringy pus coming from their mouths and nostrils. When clipping gizzards I would see large growths on the entrails that looked like a mass of jelly. These chicken entrails would smell awfully bad, and at times would make me sick at my stomach.

Sam Twedell dramatically reviewed the loathsome conditions in the Texas poultry industry before the Amalgamated's executive board in the spring of 1954. Reports by others of somewhat similar conditions elsewhere lent strength to the arguments. Upon Pat Gorman's recommendation, the board approved the launching of a campaign for an effective poultry inspection program. The union enlisted the complete support of its 500 locals, as well as the endorsement of the AFL-CIO and most of the nation's labor press. Active support came from public health officers, conservationist spokespeople, and church groups — from the national to the local level. The drive was assisted by at least a dozen national organizations — for example, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers, the American Nurses Association, the General Federation of Women's Clubs, the American Association of University Women, and the National Farmers Union. The campaign did not receive notable coverage from the mass media, though several journal articles appeared as well as syndicated columns by Victor Riesel and Drew Pearson.

The Amalgamated also approached the legislative branches of the state and federal governments. Hilton Hanna, the leading black executive in the Meat Cutters union, was responsible for most of the research and pamphleteering. He listed 34 key supporters in Congress; none were from Texas and only three were from the South. As the campaign picked up public support, the Southwestern Association of Poultry, Egg, and Allied Industries suddenly endorsed state legislation for poultry inspection but continued to oppose "federal interference." Texas Agriculture Commissioner John White took the same position, but the state legislature could not be roused. The most graphic union pamphlet, "Check That Chick," caused an Arizona state senator, known for his antilabor stance, to lose his breakfast and introduce a poultry inspection bill. Gorman and Twedell believed that federal law was best, however, and that state laws would only conflict with each other and allow the processors, through their political connections, to control the various inspection systems.

Five hearings on poultry conditions were held before three different congressional committees in the mid-1950s. Union spokespeople presented some of the Center affidavits along with statistics from the U.S. Public Health Service and Bureau of Labor Statistics. Expert supporting testimony was offered by veterinarians, doctors, sanitarians, and scientists. During the course of the hearings it was revealed that a third of all listed cases of food poisoning by the mid-1950s were traced to poultry.

Several of the chicken diseases reported during these hearings constitute a considerable risk for the workers who slaughter, process, and handle poultry. Psittacosis (parrot fever) is the most common ailment. The first outbreak in Texas occurred in Giddings in 1948, and two other epidemics struck the turkey processing workers in that town before 1954. Seven died. In May 1954, 48 workers in a Corsicana poultry dressing plant were stricken. In 1956 three psittacosis epidemics broke out in Texas, Oregon, and Virginia; 136 men and women were struck and three died.

The union's "ace" worked at Eastex. In the midst of the boycott and national publicity, after an 11-month strike, the Eastex Poultry Company yielded and agreed to a contract with the Meat Cutters. The terms of the March 1955 agreement called for wage increases of five cents an hour for women, seven-and-a-half cents an hour for men, time-and-a-half for overtime, three paid holidays each year, the establishment of a vacation system and grievance machinery, and the reinstatement of all strikers. If called to the plant, the workers had to be given at least three hours' work that day. The re-employment was with full seniority, which meant that the 20 or 25 "scabs" left in the plant had lowest seniority. The Eastex Company also agreed to submit voluntarily to U.S. Department of Agriculture poultry inspection.

As the expose began to arouse attention, the manager of the Denison plant informed the supervisor, Florence Smith, that she had been named chicken inspector and would thereafter receive her paycheck from the city of Center. The city government obediently notified Agriculture Commissioner John White that Smith would inspect all poultry for wholesomeness. (Like all of White's "inspectors," Smith lacked the guidance of any published tests or standards; Texas had no poultry inspection law.) After several days as inspector, Florence Smith discovered that the chickens she had condemned and removed from the production chain had been put back on further down the line by another supervisor. She testified, moreover, that:

It has been a regular practice to place Texas Department of Agriculture tags of approval on chickens processed in the Denison Poultry plant. These tags of approval were placed in chickens that had never been inspected. In fact, it has been a regular practice to place these tags on non-inspected chickens ever since I have been working for the company [over three years].

The struggle to unionize the Denison plant ended in abject failure — three years after the Eastex victory. In February 1958 the Meat Cutters decided to call off the strike. Both union and company were exhausted by four years of apparently inconclusive boycotting and striking. Ralph Sanders, an organizer for the union, was assigned the unenviable task of telling the picket walkers that the strike at Center had been canceled. "It was about the saddest thing I was ever confronted with," he wrote Gorman. Hilton Hanna wrote earlier that the striking Texans were the shock troops in the cleanup campaign, that they must be supported to the hilt, and that they "have demonstrated a spirit that has been rare in the labor movement for many years." Their steadfastness and zeal persuaded the Amalgamated to pay strike benefits for four years, which not many internationals would do.

Ray Clymer's unyielding position seems to have been the crucial factor in the union's defeat at Denison. The company lost most of its markets as a result of the boycott and eventually went bankrupt. According to Twedell, Clymer had an independent income which he refused to plow back into the business and preferred bankruptcy to dealing with a union. Certainly his only offer to settle the dispute reflected contempt for collective bargaining. In June 1955 Clymer offered to recognize the union as bargaining agent for six months and allow the strikers to return — with no changes in wages, hours, or working conditions — if the pickets and boycott were called off. A new election would be held in six months and if the union won, Clymer promised to negotiate in good faith.

It is also possible that the workers at Eastex, 93 percent of whom voted for the union in the election, were more determined than the Denison strikers, 60 percent of whom originally voted to unionize. Black workers recalled that a determined black union-consciousness arose. They also recollected that they were more willing to walk the picket lines than the whites.

In evaluating the impact of the strike on the town and its establishment leaders, a Chamber of Commerce spokesperson who requested anonymity declared that it was "just about the first event from the outside world to reach Center." There had never been a union in Shelby County. Companies seeking new locations at that time were notorious in demanding a depressed laboring group, and most of the townspeople and even many of the local establishment were former cotton farmers who had been driven off the land by national economic forces. They were so fiercely independent that they seemed innately to resist even thinking about unionism. They were particularly appalled that the chicken processing plants were "attacked," since it was poultry that saved the town when the bottom fell out of the cotton market in the late 1940s. The spectacle of blacks and whites walking the picket lines together at the time of the 1954 desegregation decision was deeply resented by the bigoted element; "we'd never had any race trouble," the anonymous city leader believed.

Change occurs even in Shelby County. The union has been entrenched for three decades and can hardly be considered alien. The workers, who were making $4.80 an hour (with no discrepancy between the sexes) in 1984, have never been involved in another strike. Nowadays, companies seeking new sites are inclined to inquire about local services and schools and do not seem to be searching just for low taxes for themselves. Several companies have brought unions with them. Moreover, the processing plants are not nearly as vital to the town's economy as in 1954. And the racial situation is quieter; the school system is integrated.

Of course, Shelby County did survive and, in fact, prosper. Champion editor Pinkston pointed out in 1972 that the county was growing, the banks were "filled with money," and the old hatreds had "faded away." Former strikers confirmed that bitter feelings had disappeared.

The outlook for the union in Southern poultry has brightened in the past 20 years, as the structure of the industry has changed. During the 1960s and the early 1970s the independent poultry operators were largely supplanted by the integrators, a few big vertical oligopolies that own hatcheries, feed companies, processing plants, and even distribution facilities. The trend toward major corporate ownership may have leveled off in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but agribusinesses dominate the industry. Dick Twedell, successor to his father as regional director of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters, asserts that the Southern integrators are more amenable (or vulnerable) to unionization than the independents. Though less than a third of the 30 or so poultry plants in Texas, for instance, are unionized, the one in Center, now part of the Holly Farms empire, produces more birds than half the non-union plants put together.

The roles of the union and the federal government in the nationwide drive for compulsory poultry inspection were duly noted by Senator James D. Murray of Montana. In his report that followed one of the congressional hearings in 1956, Murray spoke for the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare in praising the "definitive and thoroughly documented expose of conditions in the poultry processing industry under the Department of Agriculture's voluntary inspection program. . . ." The report deemed the department "seriously remiss" in never having called the poultry conditions to the attention of the public and in never having taken the initiative in recommending corrective measures to the president or Congress. The committee was shocked that the Agriculture Department opposed compulsory inspection even though it was in command of more facts than the union in regard to diseased poultry. The committee report added:

While we are grateful to the union and believe the American people will share that gratitude, we think it a shame that an organization of workers whose earnings are very modest should have to spend its funds to alert the Nation to a situation which is already known to a division of a governmental department which has apparently put processor relationships ahead of its responsibilities to the people of the United States.

So it was that on the national level the organizing drive in Center and the subsequent boycott and cleanup crusade scored a success for the American consumer. After a three-year, uphill fight the union overcame the opposition of the poultry industry and the Agriculture Department (which changed its position in 1956). On August 28, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Poultry Products Inspection Act, establishing compulsory federal inspection of all poultry moving across state lines and in foreign commerce. The law is supposed to assure the wholesomeness of poultry and poultry products placed on the market, the maintenance of sanitary facilities and practices at slaughter and processing plants, and correct and informative labeling.

Unfortunately, there is considerable doubt that the 1957 law (as well as the 1967 Wholesome Meat Act) is being enforced. For one thing, the tradition of "close relations" between some inspectors and plants continued. The poultry industry vigorously opposed the consolidation of meat and poultry inspection in 1969, which placed them under the leadership of officials trained in the red meat inspection traditions. Also, the definition of "wholesomeness" is constantly in flux. Standards are powerfully influenced by the Advisory Committee on Criteria for Poultry Inspection, established in 1963, comprised of veterinarians and consultants from the industry; neither its meetings nor its minutes are open to the public. There is also a distinct shortage of staff to enforce the laws. In 1971 the Dallas district office the Food and Drug Administration, for instance, had 6,000 food firms to supervise with 35 inspectors.

Even if enforced, the laws do not require the monitoring or control of microbiological contaminants in fresh meat or poultry. In the spring of 1971 a government spot check of 68 poultry slaughtering plants found sanitary conditions "unacceptable." One inspector for the General Accounting Office discovered that in one plant "the ceiling areas gave the appearance of a cheap horror movie scene with numerous cobwebs and heavy dust accumulations." In December 1972 the Agriculture Department admitted that about 465 million broilers and fryers, nearly one out of every six grown that year, went to market with illegal residues of organic arsenic in their livers. In 1979 the General Accounting Office charged that the Agriculture Department's inspection program checks for only 46 of the 143 potentially harmful drugs and pesticides that could be present in meat and poultry and estimated that 14 percent of meat and poultry reaching the public contained illegal residues.

Under the Reagan administration, inspection standards appear to be deteriorating even further. In the winter of 1981-82 the Program Review Branch of the Agriculture Department investigated the sanitary conditions in 272 poultry and meat plants. Adulterated products were discovered in a fifth of them, and in a third of the plants reviewers considered it likely that rancid products were escaping to the market. Shortly after the evaluation the Reagan administration crippled the Program Review Branch. Indeed, the administration not only is loosening enforcement standards and reducing the frequency of inspections, but also is speeding up the time pressure on a diminishing number of inspectors and attempting to prevent inspectors' reports from reaching the public.

Meanwhile, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters (now merged with the Retail Clerks to form the Food Workers Union), joined by such consumer advocates as Ralph Nader and Kathleen Hughes and such periodicals as the Food Chemical News, Nutrition Action, and Southern Exposure, continue to plead with Americans to ask more searching questions about the meat and poultry that they eat.

Tags

George Norris Green

George Norris Green teaches history at the University of Texas at Arlington. (1985)