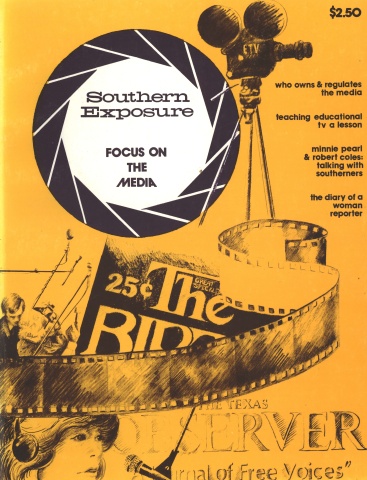

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

"There are some reasons I have for being proud of being a Southerner, and Clifford Durr is one of them." — C. Vann Woodward

Clifford and Virginia Durr who have worked for decades in the causes of civil liberties and human rights now live near Wetumpka, Alabama, in a low, rambling farmhouse set at the edge of the woods where, in the early 1900's, Clifford and his grandfather hunted and fished. Clifford attended the University of Alabama, he read law at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, and returned to Alabama in 1922 to be an attorney with a Montgomery firm. For the next few years he practiced law and worked in a political campaign.

In 1933, Clifford accepted a job with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. "I came to Washington for one year and stayed seventeen, "he remembers. At the RFC he first helped to organize the bank recapitalization plan which saved more than half of the banks in the United States. He also established and directed the RFC's work for the negotiation of billions of dollars in war production contracts.

Durr characterizes his appointment to the Federal Communications Commission in 1941 as a "political accident" involving the southern strategy of Franklin Roosevelt and the wishes of Alabama Sen. Lister Hill, a former school mate. Although he had no experience in broadcasting, he recognized the enormous power of the electronic media to influence and propagandize. During his seven year term on the FCC, he advocated a strict interpretation of the First Amendment right of free speech (similar to that of his brother-in-law Hugo Black), fought against corporate domination of broadcasting, and insisted that frequencies be reserved for non-commercial uses.

In the last years of his appointment, he battled the spirit of McCarthyism in the person of J. Edgar Hoover. Once, when asked what sort of person would be qualified to serve on a regulatory commission, Clifford Durr suggested that they might best be chosen from that group of people described by his father-in-law as, "Men that don't scare easy and women that don't rape easy."

The following interview was recorded at the Durr home, December 29, 1974.

When I went on the Federal Communications Commission, the only thing you had in the way of broadcasting was AM radio; that was the standard system of broadcasting, and there were only about 900 stations on the air when the war broke out. Well, everything was brought to a standstill because all the communications equipment being manufactured was turned over to the Army and Navy.

"My God! This Is A Terrific Medium!"

In the 1940's, the FCC was monitoring all the Axis broadcasts because we had the facilities to do it; we had linguists, propaganda analysts, quite a staff. So I began to read their daily reports. I wasn't interested in broadcasting. I was more or less a refugee from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. But I began to read these daily reports of these Axis broadcasts and then all at once I said, "My God! This is a terrific medium here. It can be magnificent or it can completely ruin you if you get this thing in the wrong hands." So then I began to take a more closer look at American broadcasting. Well, I got pretty discouraged about the commercialization, not that every hour was filled with commercial broadcasts, but the dominant theme was making money. Just by chance I read about some educational stations. You see, our educational institutions, our universities and colleges, were really among the pioneers in broadcasting. But so many saw it as only something for their electrical engineering and physics students to play with, and didn't fully appreciate the potential.

I was invited to come out to a meeting of the Institute for Education by Radio at Columbus, Ohio, to meet some of the people that had held on to their stations — generally a group around the Midwest. WHA (University of Wisconsin) was one of the leading ones, also the stations at the University of Minnesota and the University of Illinois —but they had been shoved back to inadequate frequencies, many of them daytime only because they didn't have the money to operate on.

I got pretty excited about the potentialities of this thing, and then I began to discover that in the areas served by these educational stations, the level of commercial broadcasting was considerably higher, the people began to demand something better, a little better music, a little more discussion in-depth of news. So I began to think that if we could really get some educational stations on the air, they would not only have value in themselves, but would serve as a yardstick and could contribute greatly to broadcasting throughout the country.

But there was no possibility. There was no possibility of taking the frequencies away from the commercial broadcasters. As I said, many educational stations were among the pioneers. WAPI, the big station at Birmingham, was at one time jointly owned by the University of Alabama and Auburn. Georgia Tech had a station which is now completely commercial. What happened, as the commercial advertising potential began to develop, was that the commercial broadcasters would go to these university stations and say, “Look here, you're not using but three hours a day sitting here on this frequency. You step aside at renewal time and let us come in and apply for that frequency and let us pay all the expenses for operating the transmitter, and we'll give you free time —as much as you have now." A lot of them fell for the deal and began to step aside and let the commercial stations get their licenses.

Well, what actually happened was this. Maybe a university would have a program at eight o'clock at night aimed at an adult audience that had been built up over several years. So now the station in commercial hands would come and say, "We're awfully sorry, but the network says they have got to have that eight o'clock hour. Now we can give you seven o'clock." So they would nicely go along and take the seven o'clock hour. Of course they would lose their audience until people found it again, then the audience would be rebuilt until the station would say, "We're awfully sorry, but the network wants the seven o'clock hour. How about four o'clock in the afternoon?" Well, you don't get any kind of audience at four in the afternoon. So that process continued until the universities were pretty well broken down, except a handful.

"The Biggest Thing For Education Since Gutenberg"

After I went to the meeting at Columbus, I began to work very closely with the fellows in these colleges. That seemed to me about the only hope we had to avoid complete commercial domination. Now, as the War seemed to be coming to an end, some hearings were set at the FCC to see what we would be doing with FM. FM had been started just before World War II, and it had shown its potentialities. I think there were about 40 stations on the air; they were small stations, but there were so few sets out, only about 300,000 FM sets in the entire country. These FM stations were generally run by people with licenses for standard broadcasting (AM), thus there was lots of duplication of programming which could be done very inexpensively. Great developments in the field of electronics came during the war. The British were pioneers in the development of new kinds of "valves" as they called them, rather than tubes, and they began to get way up in the higher spectrums, very-high frequencies, ultra-high, and so on. FM was changed to another range in the spectrum where you could get more stations, and they thought it would operate more effectively.

I told these educational people about the hearings at the FCC. "Look here," I said, "you haven't got a chance of ever getting frequencies taken away from commercial stations and given to you, but here is a new area of the spectrum opened up. Come in with a petition for the Commission to set aside x per cent of those frequencies for non-profit educational broadcasting." So we got up a pretty good head of steam on that. I sort of carried the ball for the Commission. Some of my colleagues were reasonably enthusiastic, but most were in the position that being against education was like being against God and Mother and Country and so on. I got them sold on the idea, and the time came when we had to have the hearings to justify the setting aside of these frequencies.

But who was going to come in and make the claim —to testify? Well, the fellows that had been doing the job around the universities were generally at the associate professor level and the average salary of a full professor in those days — except around Harvard, Yale and Princeton — was around $6000, so these guys hardly had railroad fare to Washington, and they had no prestige at all. And you couldn't get the administrators interested. They were just completely apathetic. So here was a hearing coming on, and nobody of any standing in the educational field to come in and testify to the use they could make of it and the importance. I was feeling pretty discouraged. But we went to the hearings and here were a group of presidents of land grant colleges, and, you know, they were the ones that had the political power. They took the stand one after the other and read very excellent statements about the importance of this thing to education. And the long and short of it was we set aside I think it was 15% of all the FM frequencies.

I discovered the next day what had happened. (And this is the way government operates that you don't get in your government administrations classes.) There was a guy named Ed Brecher, who is now a free lance writer, who was working for the Commission. Interestingly, his background was in philosophy. He was the kind that could put things together when you needed a report in a hurry — he was a genius for going through records and pulling out information. So I used to take Ed with me to a lot of these meetings of educational broadcasters, and he got pretty much interested in it. I found out a day after the hearing when these land grant college presidents had appeared that Ed had got on a private telephone outside of the Commission and had called all these presidents a week before, saying to them, "You're about to miss out on the biggest thing for education since Gutenberg and his printing press."

And they would say, "What do you mean?" Then Brecher would explain educational radio to them and tell them they had better be at the hearings. They would say, "It sounds good, but we'll have to think it over." "Well, don't think long because the hearings are in five days," Ed told them. "But what would we say?" "You don't worry about that; I'll have something ready for you to say when you get to Washington." So Ed spent the next few days writing the statements that these presidents read when they came to testify.

"Free Speech, For Whom?"

When I first went on the Commission, the chain broadcasting regulations had already been adopted in order to try and maintain a degree of independence for the local stations, protection from the networks. You know a network contract was the most valuable asset a station could have economically because the network was providing the revenue; they were the ones that had access to the big advertisers and provided the programs. So more and more time was network time, and less and less time went to the development of local programs, whether news discussions or art and music. The three big networks were NBC, CBS, and Mutual. Of these, NBC was the largest. (It finally became so large that it was made to divest itself of a lot of its stations, forming a new network, ABC.) There were limitations to the amount of prime time the networks could contract for. They had a way of getting what they called "option time" for which they would say to a station, "Well this nine to ten o'clock hour, you've got to give us an option on that, so if we do have a program we want to put in, we can demand that time." This meant that the local stations which had built up a program of their own would have to cancel that whenever the network wanted it.

The National Association of Broadcasters and the networks moved in Congress to get legislation to nullify the chain broadcasting regulations. Meanwhile they had challenged the constitutionality of the regulations in the court. But James Fly, the FCC chairman, was a pretty tough character. Again, an illustration of how government works: so much power is vested in men on the key Congressional committees — Appropriations Committee or the Interstate Commerce Committee which then had jurisdiction over the FCC. The networks would get to these key guys and then win them over or buy them over. But Fly was tough enough; he continued to fight this thing. We had our appropriations cut several times as the battle went on for about two years. And then we found we had more support in Congress than we ever thought. Some of the members of Congress that were not on the key committees began to understand what was going on. So not only was the case won in the Supreme Court, but Congress ultimately defeated all the legislation to nullify the chain broadcasting regulations. I don't think that turned out to be too effective, but it helped some on the monopoly standpoint.

About this time I got interested in trying to show where the economic controls in broadcasting really lay. We had a very good guy as head of the economics section named Dallas Smythe, who turned up the data. And I wrote an article which was carried in the Public Opinion Quarterly at Princeton, entitled "Freedom of Speech, For Whom?" I said, "Well, we talk about government control but let's just see who's really running the show." Here were 900 stations on the air —you'd think that you would have enough diversification in programming and in ideas. But you take a look at it, and 85% of the coverage of these stations was by stations that had a network affiliation contract. And the networks not only controlled the time they used for network programs, but they could bring a lot of pressure to bear on the stations as to other programs they carried. For example, a station might have a local program that did not have too large a listening rating, but did have an enthusiastic audience. The networks would say, "We don't want all the sets off when our network program comes on, you've got to put a more popular program in that time period." So they were doing a lot of dictating of programming.

When you took a look at the networks, you found that they were not such free agents themselves. Network advertising is per se national advertising. You take a local newspaper of that time and the advertising revenue was about 85% local and about 15% national or regional. You had the reverse situation in the case of the stations and the networks. I found that something like 20% of the revenues of each network came from one national advertiser. And something like six national advertisers provided more than 50% of the revenues. Well, you follow that through into advertising agencies and you find even more concentration because an agency might handle quite a number of accounts.

"Not The Best Applicant But The Biggest Liar"

I suppose program-wise, the most significant development came with the so-called "Blue Book," the report on the public service responsibility of broadcast licensees, which was issued in a blue cover. It created quite a bit of consternation. This happened after Fly had left the Commission and Paul Porter had become chairman, a very likeable guy, but quite a politician. Ordinarily, renewals of licenses were brought up by the engineering department in batches of anywhere from ten to twenty at a time: "We have no interference problems, no technical problems at this station, we recommend that their license be renewed." And the Commission would just say, "Renewed." That was all there was to it.

Well, I had gone along with this —this was the way they had done things, for quite a while. Then I just happened to take a look at the Communications Act one day and it said, "All renewals shall be governed by the same considerations as original grants." In making original grants, the Commission traditionally, going back to the days of the old Radio Commission, considered proposed program service as a very important element. And very often you might have several applicants for one station, and the grant had turned on the proposed program service. So, after I took a look at the provisions of the Act, when the next batch of renewals were presented by the engineering department, I said, "Well, wait just a minute here. We haven't got enough information. We're acting entirely on engineering reports." The response was, "This is the way we've always done it." "But," I said, "that's not what the Act says. And I want the record to show that I am refraining from voting because of lack of information."

The Commission also had required every station once a year to present a composite program log. But these composite logs had gone right into the files, nobody had even taken a look at them. So from then on, when a group of renewals appeared on the agenda, I would get a member of the staff to go down and get the original programming proposals and compare that with the latest program log. And I found out that there was no relationship between promise and performance. There were all these promises about the agricultural programs, and the music programs, and how they were going to develop the community, and discussion programs, when actually 85% of their time was going to network programs or "platters" (disc jockey shows). So I laid the promise and the performance beside each other and I said, "Look here, here's what this guy's doing. We're granting it not to the best applicant, but the biggest liar. This is not fair to the public nor the competing applicants."

So this thing began to build up for months. Every time I would be ready with the dossiers. Finally —you know in government, when the evidence builds up to the point where you've got to do something, you have a study. So I said, "Well, I think we ought to have a study." I was appointed to head up the study and given a little money to hire two or three people from the outside, including Charles Siepman, who was quite knowledgable about broadcasting. I put Dallas Smythe and Ed Brecher of our staff to work on it, too, with the result that instead of this study dragging on for a couple of years, in a month it was completed. That really baffled them; there was nothing to do about it but go along. Now everybody thought that there was going to be hell to pay, but the public's reaction was just remarkable: "God, this is great! Now if the Commission will just make the stations live up to this, we'll have good broadcasting."

We said that the stations which did not live up to their promises were going to be set for a hearing, but I think I am the only member of the Commission during those years that ever voted not to renew a license. Charles Denny was now Chairman. He'd go around all over the country making these speeches, "The Blue Book will not be bleached." But whenever a station came up for renewal, they'd give them a lecture, instead of taking away their license; and so, gradually the process began to drift back into the old pattern.

The Avco case was another dispute that attracted a great deal of attention. My position was that broadcasting ought to be run by broadcasters and should not be permitted to become a mere adjunct of large business concerns. Not only would it be unfair from the business point of view, competitively, but I thought that you had to have people devoting their full time to considering the effect of broadcasting on the minds and emotions of people. Well, one of the biggest stations in the country, a 50 kilowatt station, WLW, operating out of Cincinnati and blanketing the whole Mississippi Valley was owned by the Crosley family. They came to the Commission with an application to approve the sale of the station to the Aviation Corporation of America. I insisted that it be set down for a hearing — it was one of the most important stations in the U.S. Paul Porter, who was still Chairman at the time, and the other members agreed to go along with the hearing.

The high officials of Avco said, "We're buying the broadcasting properties as part of a package. We're more interested in the Crosley manufacturing facilities." They hadn't the slightest idea what the responsibility of a broadcast licensee was, or even what broadcasting was all about. But they had on the board of directors a fellow named George Allen, a lobbyist around Washington, a funny guy who told good stories and, as a result, had access to most anywhere. So they put him on to testify, and he made some wisecracks. I knew right then what was going to happen — Paul Porter was going to go along with him. The sale was approved, but I wrote a dissenting memorandum (Commission members Wakefield and Walker also dissented). The Avco case became one of the key policy decisions.

"Balance Between God and Free Speech"

Besides the Blue Book, the ruling that attracted the most attention — and got me in the most trouble —was the Scott case. You know, nobody can be more devout than a devout atheist. Scott was a retired court reporter out of San Francisco. He was an atheist who made it his lifetime cause to see to it that the atheist point of view was broadcast. So after the Blue Book came out and we had talked about the responsibilities of stations to present all points of view, Scott had approached the three leading stations in San Francisco asking for time and they had all turned him down. Then he proceeded to draw up a formal complaint, asking that the licenses of the stations be set down for hearing on renewal. And it was a pretty intelligently done job. He said in it, "I'm not the kind of fellow who goes around throwing bricks in church windows or scoffing at people kneeling in prayer. I respect a person's right to have the religious views he wants, but where I part company with them is when they say I can't present the atheist point of view. I don't want to berate anybody; I just want to make a rational presentation of the atheist argument. As far as balance is concerned, these stations are giving free time to religious broadcasters and they are letting a lot of these preachers get on who devote themselves to attacks on atheists, saying we are irresponsible and criminally inclined because we don't have the sanction of a belief in God, and I think we are entitled to be heard."

So the Commission did what it normally did — sent the complaint to the stations and asked them what they had to say about it. Well, one of the stations came back with a very intelligent response. They said, "It's all a question of the degree of interest in an issue. Unlike a newspaper that can add another page, we can't add another hour to the day. If every single point of view is presented, we'd have to be giving time to people to prove the earth is flat, and all of that. But with a showing of enough interest and assurance there would be a responsible presentation, we think it ought to be considered." The other two stations got very righteous about it: "It would be contrary to the public interest to ever permit the cause of atheism to be heard on the air. We will not permit that."

So the Commission was on a spot. They said, "Let's just dismiss that with a simple order of dismissal." I said, "Now if we just dismiss this with an order, in the public mind it will be taken as a confirmation of the position that these two righteous stations took. I'm not going to vote for revocation of license or even a hearing, but I want my views to go out as a notice to the broadcasters and the public generally. Then we can be specific about it and next time take more drastic action."

I wrote a memorandum relying upon the first amendment and going back to Lincoln and Jefferson, neither of whom would have been allowed on the air because he was accused of being an atheist. And I must have hit a right balance because the Commission didn't want to be against God and they didn't want to be against freedom of speech either. So, much to my surprise, they agreed to adopt my memorandum as a unanimous statement of the Commission's position. Well, ordinarily the Commission's decisions are issued over the name of the secretary unless there is a dissent, then the dissenter's name is listed. Though I didn't care, it got out that I had written the decision and Sol Taischoff of Broadcasting magazine came out with an editorial strongly for God. And from then until I left the Commission he would attack me about every other week in his magazine. Also, I began to hear from the good religious folks. Some were telling me how hot hell was, and others were saying they were going to see to it that I got there quick.

"J. Edgar Hoover and I Had A Slugging Match"

Running through the 1940's was the Red hysteria. We came through the War with civil liberties pretty well intact, except for the horrible Japanese internment thing out in California. We didn't get worked up as much as we did during World War I when anybody that had a German name was in danger of his life. But I did get involved (I won't go into that in detail), soon after I was appointed to the Commission. Martin Dies of the Dies Committee made an attack on a Commission employee, a man by the name of Goodwin Watson who was a social-psychologist who had come down from Columbia to head up the propaganda analysis section. I had had nothing to do with hiring him; he had been on the job several months and was doing excellent work when Martin Dies writes the Commission and says, "This man is socialistic and belongs to the following communist front organizations and I demand that he be fired forthwith."

This was about December, 1941, right after Pearl Harbor. He didn't call us quietly and say, "I've got some information you had better check into," but he hands his letter to the press before he puts it into the mailbox. So we hear about it first in the Washington Post. Because I had nothing to do with hiring the man, the other members of the Commission ask me to check into the charges. I didn't even know this man, so first I sent for his personnel folder and he had some pretty strong recommendations from some solid people in the academic field. He had also been commended a number of times even by the military because he had called several of the German military moves from some of their propaganda. So next I asked Watson to come over and questioned him quite seriously for about five minutes and then I began to scratch my head and say, "There's something funny going on here. Maybe I had better know about some of these communist front organizations. This fellow impresses me as being of pretty substantial character."

I got the staff to bring in some of the literature of these organizations; let's see who else are members and what their cause purports to be. Well, the next day they were back with their first "communist front" organization, The League for Non-Participation in Japanese Aggression, the chairman was Henry L. Stimson and the vice-chairman was Admiral Yarnell. It was set up right after Japan had invaded China, and the general idea was, "For God's sake let's put an embargo on oil and scrap iron going to Japan, because if we don't she's going to be throwing it back at us" — which, of course, she did. The next was the Council Against Intolerance in America. On its national board was Alfred E. Smith, who had run for President; Tom Dewey; William Green of the A.F.L.; Senator Carter Glass of Virginia, who was a little to the right of Senator Taft; and about every religious leader that had any national reputation, Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish. The best I could figure out, their function was to sponsor Brotherhood Week.

The long and short of it is that I got this whole list of organizations and among the members were twelve senators, every member of the cabinet, thirty-six members of the House including Jerry Voorhis who was a member of the Dies Committee (and by their standards a communist on three counts), five members of the U.S. Supreme Court, led by Charles Evans Hughes who was on the Marian Anderson Concert Committee — you remember that the Daughters of the American Revolution wouldn't let Marian Anderson, the great singer, hold a concert in Constitution Hall because she was black. Chief Justice Hughes got busy and helped stage her concert on the steps of Lincoln Memorial where she had an audience twenty times the capacity of Constitution Hall.

Anyway, the Commission refuses to fire Watson by a 4 to 3 vote. We issue a public statement saying that we couldn't fire a man on charges such as these. The other three's attitude was, "Well this is all absurd; this man is doing a good job and we'll have a hard time finding anybody that can take his place, but what does one man matter anyway? We've got to consider our relations with Congress, let's fire him."

After we refused to fire him, the next thing we knew a rider was on our appropriations bill, "No part of this appropriation shall be used to pay any compensation to Goodwin Watson." So I got busy doing a little lobbying in the Senate, including Harry Truman whom I knew well and had done some favors for, and Alben Barkley the majority leader, young Bob LaFollette, George Norris, and a few of that type. When this bill hit the Senate it was rejected unanimously with Senators saying such things as, "When the Congress of the United States begins to concern itself with a man's politics and what he thinks, we're going down the road to Nazi Germany."

The next thing I knew I was being investigated by the F.B.I. I have read my F.B.I. file, which was quite amusing. I was "respectable," but my wife, according to the communist Daily Worker, had appeared before a committee of Congress and made a statement in opposition to the poll tax as a pre-requisite for voting in a national election. It was also "according to the Washington Post, the Star, the Baltimore Sun, the New York Times," but it was "according to the Daily Worker" and what F.B.I. man worthy of his badge would pay any attention to what the capitalistic press had to say? The thing finally went to the Supreme Court in the U.S. vs. Lovitt, Watson and Dodd, where the Court unanimously ruled in our favor.

We relaxed during the rest of the War, but when Roosevelt died, and the atom bomb came on, hysteria began to build up. J. Edgar Hoover started sending us gossip he got on applicants for radio stations or news commentators. Congress was scared of him, and he had his key men on Congressional committees. We had been in a constant battle ever since I came to the Commission over wire-tapping legislation. Every year almost, Hoover would try to get some legislation through authorizing him to wiretap under the Communications Act. He put in "national security" considerations and all of that. But FCC Chairman Fly was a good, tough civil libertarian, if nothing else, and we would beat them in Congress every time on that issue.

Finally, these pressures began to build up on the good newsmen and the commentators, and in time it went on to some of the actors, performers, and musicians. But it came to a head with the application of the Hollywood Radio Corporation, a group in Los Angeles who were drawn from U.C.L.A., University of Southern California, and quite a number of people in the movie and radio field. They wanted to begin a commercial station that was program oriented, for people primarily interested in good broadcasting. Well, a letter comes to the Commission addressed to the Chairman from Mr. J. Edgar Hoover saying that it has been brought to his attention that the majority of stockholders in this corporation were communists or actively engaged in communistic activities. So we write him back asking for his evidence. And a letter comes back, "Of course I can't give you that for it would disclose my confidential sources. But here is some relevant information." One I thought was a classic was, "This individual in 1944 was in contact with another individual who was suspected of possible pro-Russian activities." (In 1944, Russia was our ally and Russian relief was the thing.) And then another university professor had made a Phi Beta Kappa address urging that we try to set up a cultural exchange with the Russians.

The Commission then sent a couple of lawyers out to Los Angeles to see what they could find about these communist activities and they came back to report that most of the Hollywood group were members of the Democratic Club and had been very active for Roosevelt in '40 and '44. In spite of this, the Commission didn't act at all. They had visions of going before the Appropriations Committee and some Congressman saying, "Didn't you grant a radio license to the Hollywood Radio Corporation after having received derogatory information from J. Edgar Hoover? Well, off goes $500,000 of your appropriations just to show you."

So they just sat on this thing until I decided that it had to be brought out into the open. I was invited to make a speech to an education group out in Chicago. About this time Tom Clark was Attorney General, and we sent the Freedom Train around the country, cars painted red, white, and blue, with the original Declaration of Independence and the Constitution so the school kids could see it. Also at this time Parnell Thomas was chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, and he began to move into Hollywood. So I decided I had to blast this thing out some way because we were really in violation of the law, denying an application by non-action. I took this occasion to sound off by digressing from the main thrust of my speech to say, in effect, "While the Freedom Train is going around the country carrying all these documents, things are going on in Washington that refute every document on that train. Don't get the idea that this well-lighted affair of Parnell Thomas' is just a one-time Hollywood show, because what happened there is going to permeate the broadcasting industry. It's going to be in our schools and universities and going to wreck the country. Moreover, as bad as it is, I think these kleig-lighted lynching bees are not as dangerous as the secret dossiers that go into government files which the applicant doesn't even know are there, but which can haunt him the rest of his life. If you could see some of these F.B.I. reports, as I have done, I think you'd have to agree with me that much of it is little more than baseless gossip."

Columnist Mark Childs heard about my speech and in a couple of days came out with an article saying he thought I was a responsible public official and, if this kind of thing was going on, it was Nazi stuff. He wrote a very powerful article. The next thing that came about was Mr. Hoover's writing the Commission: "Unless all the other members of the Commission repudiate Commissioner Durr, I will assume it is no longer interested in any further information from me." Well they were all just scared to death. My relations, with one exception, were always good ones on a personal basis, so I said, "You know I have a reputation of being something of a dissenter, and was not purporting to speak for the entire Commission. But if you feel like you have to repudiate me, I realize there will be nothing personal in it." So they sweat over this thing and, though they couldn't bring themselves to repudiate me, they came out with a letter saying that they had the utmost confidence in the F.B.I. and wanted to continue getting this information.

I took this occasion to get some things out publicly. So I wrote a memorandum to go out with the Commission's letter. In this I said that the Commission should welcome, from any source, information pertinent to the performance of its duties. But when it comes to act, that information must be under oath and subject to cross-examination. Then I proceeded to paraphrase all the crap that was in the F.B.I. report. Well, the fat was in the pan and Hoover and I had a slugging match the rest of the time I was on the Commission.

"I Admire What You Are Doing, But. . ."

I opposed Truman's loyalty order and I wrote a dissenting opinion on that. But Truman, nevertheless, offered me reappointment. I turned him down because, as I told him, I couldn't be part of having to administer this loyalty program. His response was, "I got to take the ball away from Parnell Thomas. If he has his way, he'll get some legislation through and we'll have the damnedest gestapo any country ever had, and I don't want J. Edgar Hoover running this country. All I want is to protect these people."

I said, "Mr. President, I don't think you realize the effect this is having on the morale of government employees whose loyalty has been demonstrated in war and peace. You sit there and accuse us in F.B.I. reports with anonymous informers. The mere charge against a man can ruin him. You don't realize how the morale is going to pieces and moreover, more seriously to my way of thinking, is not Parnell Thomas, who most people see as a political demogogue capitalizing on this red hysteria, but you coming along with this loyalty order. People look at that and say, 'My God, Parnell Thomas is right. Here's the Government, according to the President himself, so infiltrated with dangerous subversives that every federal employee, no matter how insignificant his job might be or how far it might be removed from any considerations of national security, has got to be checked by our secret police.' That's going to destroy confidence in government."

"Well," Truman says, "this is all a bunch of crap. The Government employees are as loyal as any people ever were. All I want is to protect these employees. I'll amend this order if necessary, I'll repeal it."

He issued a very nice statement expressing regret that I wouldn't take re-appointment. He was about to enter the '48 campaign and had enough problems so I just let him issue the statement. He had been magnificent in the Goodwin Watson case in the Senate, but he got caught up in the '48 campaign—go back and read the Truman-Dewey speeches. "I'm a bigger anti-communist than you are, so there.” The hysteria just grew and grew.

I stayed in Washington and thought I was going to have a pretty good law practice. At first I wanted to teach. I had received a number of feelers, including the Yale Law School, but after I got in this last battle with J. Edgar Hoover, all these things just died out. My clients would meet me on the street corners and tell me "I admire what you are doing, but I've got to get a more conservative lawyer." So the first thing I know I was representing nobody but the victims of these loyalty cases, particularly before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. That ended my possibilities of making a living practicing law in Washington.

Tags

Allen Tullos

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1978)

Allen Tullos, special editor for this issue of Southern Exposure, is a native Alabamian. He is currently in the American Studies graduate program at Yale University. (1977)

Allen Tullos, a native Alabamian, is a graduate student in folklore at the University of North Carolina. (1976)

Candace Waid

Like Cliff Durr, Allen Tullos and Candace Waid are native Alabamians; both are pursuing their interests in the South as graduate students — Allen in folklore at the University of North Carolina and Candace in women studies at George Washington University. (1975)