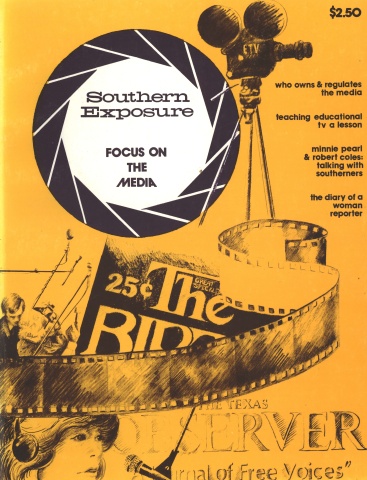

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

A chief news editor at CBS put a tape on the playback machine and called a few of his colleagues around. It might have been standard procedure for the New York staff, which works in shifts around the clock, handling reports that pour into the newsroom from CBS correspondents around the world. But the editor treated this tape differently. He wasn't calling his staff together to decide whether to use the tape on the news. He had already heard it once and was now calling his staff together for a laugh.

From the newsroom speaker boomed the drawling voice of a Tennessee lawyer concerned with the image of his profession since Watergate's disclosures. The attorney was telling a Washington meeting of lawyers that they should face the damage to their profession squarely, and, as he put it, "belly up to the buzz saw."

Everybody listening laughed. The tape was such a social success that the editor ran it again a little later for some people who had missed the first playing, and it drew another round of laughter. If this incident showed only that the staff appreciated a crisp figure of speech, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But several of the people who listened to the tape started smiling before the lawyer reached the "belly up" punch line. His manner of speech amused them, as well as his figure of speech. They wanted to laugh at him.

Another tape revealed the newsroom's sense of humor again. A prisoner was telling a CBS reporter how he had been taken hostage by some other convicts during a brief uprising at an Appalachian prison. His story contained nothing to laugh at. His accent, though, was straight out of the hills. The head editor ran the tape three times that afternoon, with the volume turned up. Each time, the newsroom rang with laughter. The CBS news team thought the man's accent was screechingly funny.

The hilarity did not end there. Some people tried to double the fun by mimicking the accent as best they could. One young woman spotted a newscaster, a native of a small Appalachian town, working at his desk and chewing a matchstick. She launched into a speech about "land sakes alive and lawdy me how downright surprisin' it was to see a purebred downhome cracker make it in the big city and land a job with CBS." He sparred with her awhile to be polite, and then ended the game. Her New York City humor had struck a little too close to home. She was implying that if a person from the Appalachian mountains could somehow get into the central CBS newsroom, it was a mistake. Hillbillies don't belong there. To her and others at CBS, the southern mountain accent was not merely amusing: it was also a mark of ignorance and incompetence.

In fact, these accents struck the staff as funny only because so many of them regarded such inflection as the sign of lame brains. Three men much in CBS news lately —Henry Kissinger, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, and Israeli Foreign Minister Yigel Allon—all speak English with accents as distant from standard American speech as the convict's or the Tennessee lawyer's. But editors do not play back tapes by these men and gather the staff around to chuckle. The staff regards them as intelligent and able. Therefore, their accents are not laughable, no matter how peculiar compared to the staff's own speech. In contrast, the Appalachian accent is a panic.

CBS has a relatively new reporter specializing in legal matters who previously worked on newspapers, where he didn't have to correct his accent. His voice sounds like it comes from somewhere far south and somewhat west of New York City. One afternoon someone asked an editor across the newsroom if he had any tapes coming in. A story was due from this reporter. So the editor shouted back, loudly, "We'll have one in ten minutes from our crack court reporter —or should I say our cracker court reporter?" When your native accent produces treatment like this from your colleagues, the rational lesson to learn is to conform. Refining your speech stands out as the first step.

Although folks from the hills are ridiculed in the CBS newsroom, they are not alone, if that's any comfort. Jokes with punch lines aimed at other minorities are socially acceptable. People with names that sound Italian can be talked about in terms vaguely suggesting that they are ridiculous or sinister. Among foreigners, Arabs are a fair target. But among the regional, ethnic, and social groups of America, openly-expressed prejudice in the CBS newsroom clearly falls hardest on all people out there somewhere beyond the Hudson River, known as hillbillies, crackers, or rednecks.

I.

If the same prejudice against Appalachians existed on, say, the staff of a Bulgarian fishing boat or a lumber mill in Maine, this would be a strange situation — worthy of a laugh or two perhaps. When it is true in the newsroom of a major network, a serious question comes up: what effect does this have on the way the CBS radio network reports the news?

It certainly affects what goes out over the air. Every major broadcaster and newspaper receives much, much more information than it sends out as news. For each line of news that actually goes out over the air, hundreds are thrown away. The minute-by-minute decisions about what to keep and what to discard shape the news. Simple ignorance can not explain how some news is consistently dropped or distorted. An old saying claims that familiarity breeds contempt. But contempt also breeds unfamiliarity. When the CBS staff faces heaps of information, it makes choices to cover the events and people that best mirror its sensitivities and prejudices. Other perspectives are simply ignored. For example, on many occasions—like presidential speeches—CBS telephones various "important" people to get their reactions. Names well known to the staff come first to mind, and they get most of the calls. Frequently-called senators come mainly from the Northeast and the West Coast, plus a couple from the north-central states. Such attention helps them become famous and powerful, as well as effective advocates for the areas and interests they represent. CBS does not normally call Southern or Appalachian spokesmen for their opinions.

This fixed sense of what is important and what is not, of who counts and who does not, also affects how news items are covered. Take, for example, last year's squeeze on the independent truckers and the strike that it produced. At its height, the CBS radio network carried reports almost every hour about the "violence" as some striking truck drivers tried to "force" reluctant truckers to shut down, too. From the truckers' viewpoint, when fuel prices and speed limits make it impossible for them to clear enough money for the payments on their rigs and food for their families, then they too are being "forced" off the road, and "violence" is being done to them and their families. Yet CBS never used such words to describe the actions of the oil companies and government. CBS stories about the truckers did not simply report the facts; they also encouraged the listeners to look down on the truckers. Respect, according to the network, is reserved for the urbane, relatively rich, politically powerful.

Another example illustrates how Appalachia, which ranks close to the top in poverty and powerlessness, ranks close to the bottom at CBS news. When a heavy rain eroded the Pittston Coal Company's gob pile dam at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, three years ago, more than a hundred people perished. Hundreds of others were injured and had their homes swept away. The first few days after the disaster, CBS covered the story. Since then, CBS has not reported on related developments: the court cases against Pittston, inadequate Federal assistance, the psychological pressures on the survivors, and the general problem of coal waste disposal. The continuing story of Buffalo Creek's attempt to rebuild a community is not as important as the single devastating torrent that rubbed it out.

Contrast CBS' treatment of Buffalo Creek with its zealous —and legitimate—concern for the denial of human and civil rights by the Soviet government. CBS decided to focus attention there and has kept it there month after month. This attention creates interest, awareness, and pressure. A bill making trade with the Soviet Union contingent on the loosening of emigration passed Congress this year, largely because CBS and other media turned complaints about the denial of civil rights in the Soviet Union into a persistent news story. Are the rights of the people at Buffalo Creek any less basic and human than those of the people in the Soviet Union? If CBS had publicized the dangers of coal waste dams before the disaster, could 125 lives have been saved?

Tragedies are not inevitable. CBS could help prevent them. If, for example, CBS would report week by week the toll of mine fatalities, it is reasonable to suppose that within a short time labor, industry, and government would be pressured into making U.S. mines as safe as foreign operations. Instead, CBS will wait until a methane explosion kills a large number of men in a single instant and continue to ignore the higher number of fatalities accumulating from slate falls and haulage accidents.

These seem like obvious, useful, and necessary ways to employ the influence of a national news network. They wouldn't even require the newsroom staff to alter or abandon its job, which is gathering and reporting the news. It's not that mine safety and dozens of other events in Appalachia are not newsworthy; it's simply that CBS has other interests.

II.

Moaning about the activities of ''big government is a popular pastime in many parts of the United States. Government agencies of all sorts poke their fingers more and more into the daily lives of ordinary people. At the same time, however, the major concentrations of private power — namely, the large corporations, including CBS— operate with enviable freedom. Anyone possessing great power checked by few controls over its daily use may dream at night of piracy. The owners and managers of America's great concentrations of private wealth have sometimes surrendered to the temptation.

Ordinary citizens, sensibly enough, have wanted some watchdogs around to sound an alarm when the breeze carries an odor of piracy. Common people have relied mainly on two sources for these watchdogs: unions and government. Both have failed to do their jobs in many ways, but there simply have not been many other places to seek help.

Network broadcasters are supposed to help with the watchdog job. CBS and the other big-time media have indeed been watchdogs —of a certain sort. In particular, they have devoted much energy to exposing abuses and excesses in the government and the unions. The major media uncovered the Watergate crimes, and they took a big hand in ending the career of Tony Boyle as head of the United Mine Workers of America, for example. But could they have prevented the energy crisis if they had regularly turned as sharp an eye on the presidents of the seven major oil companies? In short, the media — including CBS —have been much busier hounding the watchdogs, than keeping an eye peeled for the skull and crossbones.

Perhaps the news media like CBS could offer themselves as protectors of the public interest. Through their network control over public communication and their budgets, they surely have the ability to report the news in ways that would make them awesome defenders of ordinary citizens everywhere. But the suggestion looks silly as soon as it is made. To carry it out, week after week, CBS would have to challenge and embarrass publicly the very companies that it does commercial business with every day.

Beyond this, the members of the news staff do not have the attitudes necessary for such an approach to the news. To raise a persistent challenge against the abuses and excesses of power, they would need personal commitments to the effort. They display, instead, a large capacity for overlooking such abuses, plus a personal inclination to indulge in the same thing themselves.

Several months ago, the word leaked out that President Nixon had shrunk his personal taxes almost to the vanishing point by giving the government his vice-presidential files and papers. It was a scandal, thoroughly and critically reported by CBS. A couple of CBS reporters were discussing this one day in the newsroom. One of them mentioned that Walter Cronkite, CBS' most famous star, had done the same thing. According to the reporter, Cronkite had given a load of his old news scripts and other such "worthless stuff" to a journalism school and then subtracted it from his income tax return as a donation. The two reporters discussing this shortchanging of the public purse did not hesitate a second in shock or amazement at the idea of Cronkite's deducting "worthless stuff." They laughed. Then they went back to work. The truth of the reporters' conversation is immaterial. That they were undisturbed by the picture of Cronkite's slick maneuver is the point to remember about CBS.

(Editor's note: Speaking through a CBS spokesman, George Hoover, Cronkite claims that his donation of "scripts and correspondence" to the University of Texas at Austin was not claimed as a federal tax deduction. He offered no evidence to support his claim, however. Hoover argued that even if Cronkite had taken the deduction, "It was legal, wasn't it?")

For CBS to become a true defender of the public interest against both public and private abuses of power, it would have to dedicate itself to exposing its own newscasters and advertisers with as much zeal as Richard Nixon. CBS will never develop this dedication, for doing so would breed public anger against big business, just as all the news about Nixon and the Watergaters has bred suspicion toward government in general. And, the CBS Board of Directors — whose members also direct Atlantic Richfield, AMAX, Union Pacific Railroad, Pan American Airways, American Electric Power, Eastern Air Lines, Borden, Cummins Engine, Corning Glass, among others —would not want to see the CBS News team focus the public's attention close to their homes.

It's one thing for CBS to fault unions and the Nixon Administration; criticizing blocks of private power is something else again. CBS News knows where its bread is buttered.

Tags

David Underhill

David Underhill worked in the New York CBS news room as a "transcriber of electronic transmissions" (typist) to finance his graduate study at Columbia University. He has published in various political science journals, been on the staff of the Harvard Crimson and Southern Courier, and currently lives in Mobile, Alabama. (1975)