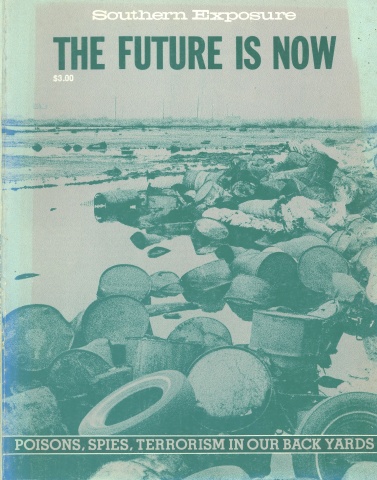

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

Not long ago, a local citizens group in rural northeastern North Carolina got some unexpected help when they started a campaign to change the admissions policy of Maria-Parham Hospital so poor people would not have to pay deposits before being admitted.

A community radio station, WVSPFM, featured frequent and detailed reports on the Assembly of Vance’s* organizing efforts, providing information carried by no other media in the area. When the campaign culminated in a mass meeting at the county courthouse, WVSP aired the entire four-hour meeting live.

“They magnified our audience all over the county and beyond,” recalls Kenneth Smith, one of the campaign’s chief organizers. “It was an electrifying and stimulating experience, and the mass attention they gave people’s dissatisfaction with the hospital had a dramatic effect.”

A few days after the hearing, the hospital made several basic concessions on deposits, hiring blacks and improving staff attitudes toward black and poor patients.

Located over a beauty shop, one block from the main crossroads of tiny Warrenton, radio station WVSP has been living up to its call letters — Voices Serving People — since it first went on the air in August, 1976. By giving people a sense that radio is a medium for two-way communication, it is a model of information sharing that goes beyond the normal idea of broadcasting programs at listeners. It is the only rural, community-based National Public Radio (NPR) member, and the only listener-supported, non-commercial, rural, black-controlled station in the country.

The roots of the station and its bonds with the community it serves go back to 1973 when activists living and working in the incredibly poor black belt counties of North Carolina met to assess the region’s needs and possible solutions.

“We didn’t decide that radio was more important than housing, or housing more important than education or health or whatever. We saw, however, that it would perhaps be possible for us to have some impact on all those areas with a radio station,” says Valeria Lee, who grew up in Warren County and is now the station’s general manager.

“You ran down the dial and you had a choice of country, soul, gospel and easy listening. Not much by way of information, variety or entertainment. We knew there could be something better.”

A lot of trial-and-error went into those early days. None of the original staff had any experience in running a radio station. Valeria Lee was a high school guidance counselor. Her husband Jim, who became news director and engineer, knew virtually nothing about radio technology. Without wealthy backers or on-the-air experience, the founders learned to rely first and foremost on their personal tenacity and political commitment to a vision of public radio pieced together from sources as diverse as an FCC handbook on “How to Start a Broadcast Station to a first-hand trip to Cuba to see rural radio in a revolutionary context.

During one three-month stretch in 1977, when funds nearly dried up, three people — Valeria and Jim Lee and Walter Norflett — managed to maintain the entire 18-hour day themselves. “It was a desperate situation,” Norflett remembers. “We just refused to let the station go under. We sat with our faces looking toward the meters, but I can’t say our brains were alert.”

Not having enough money or people is still the station’s biggest problem, although now the budget runs over $175,000 and there is a fulltime staff of nine. Staff complaints about too many 12-hour days and seven-day weeks and too little equipment are only muted by their senses of humor and concern for the work.

“Some days I feel like my goal is to take too little time and too little equipment and try to get something out there that folks need to know,” Candy Hamilton says. “Other days, when I’m more up, I feel we have a chance to share our resources with people who can perhaps gain more control over their fives by having more information or seeing ways they can become involved.”

With huge projects like covering the hospital campaign or the multi-year organizing of J.P. Stevens plants in nearby Roanoke Rapids, it’s easy to see how Hamilton and the two other members of the station’s news staff get stretched thin. The same expansive, community orientation permeates every aspect of WVSP. Indeed, its triple focus for programming flows directly from a recognition of the unique mission and condition faced by a radio station serving a largely black, rural audience, as expressed by Valeria Lee’s statement to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting: “To be black and a part of the rural South and not have access to the blues or jazz or African music was to be denied access to our culture; to be removed from the power centers and not have access to detailed reports of national and international developments fostered isolation; to have as models the urban experience without recognition of contributions of minorities and country folk was to foster notions of second-class status.”

The three pillars of the station’s 19-hour daily schedule, which rest on this philosophy, are music (“mostly jazz”), news from NPR and the in-house staff, and community-oriented shows that involve one segment or another of the potential listening audience of 350,000 — including shows for young children, teenagers, consumers, and a nightly call-in show, “Community Expressions.”

Serving as an alternative source of information and entertainment has not been easy. The challenge of fulfilling WVSP’s two-way communication potential is even harder. For example, the “Community Expressions” call-in show is still plagued with a lack of listener participation. “Too many people have come to think that what they say and think isn’t important,” explains David Cole, host of the 90- minute program.

Georgia Collins, the station’s development director, believes the lack of interchange is due to the deep-rooted belief that listeners have no role or right of participation. “People have been trained to look at the media in passive kinds of ways,” she says. “We are reaping the results of adults who grew up with media without having any understanding of how it can be used.”

Cole also cites as a deterrent the fact that many listeners have to call long-distance, a financial burden the station can’t relieve because of its own limited resources. Some shows, however, spark heated debate. The night the six Klan-Nazis were acquitted in Greensboro “the phones were fit up for the solid program,” says Cole.

Staff member Jere King believes that changing the view of radio as a one-way medium must begin with children. Toward that end, she produces “Tickle Me Think,” a 15-minute morning program designed for five-to-eight year olds.

“The biggest thing I try to do is expose kids to different kinds of cultural activities,” says King. “There’s a lot of songs and traditional folk pieces. In the series, ‘The World is Big, The World is Small,’ we hear a lot of international stories. It lets kids know to look around the world for ideas.” Closer to home, King has featured kids reading stories selected in a countywide competition.

The popular afternoon program “Let’s Rap,” produced by teenagers involved in the station’s Health Education Project, also “gives kids a kind of outlook on how to take care of their problems,” Vince White says. White, 21, is a volunteer who works with eight VISTAs hired by the station under a grant to introduce teens to health issues. As with several other special projects begun by the station, it’s not always easy translating education and service projects into quality radio programs.

Mary Taflinger, another VISTA, says she found it frustrating at first to use

“Let’s Rap” as an organizing tool. “Initially it didn’t seem like anybody was interested in the health aspect of it. All they wanted to do was discjockeying. But later we found it allowed us to get to know the kids a little better and then find out where their interests are.” “Let’s Rap” still mostly features disco music, but the teens also produce audio spots on health, poetry and a daily newscast. In addition, the Health Education Project and Warren County students produced a one-hour program on adolescence called “Changes: Feeling Good About Growing Up.” Five other features are planned for this year on nutrition, chronic disease detection, VD, teen pregnancy and drug abuse.

The Health Project has also performed a radio drama entitled “How the Junk Floyds Took Nutritianne.” The drama is about how the Floyds “took this lady who was teaching nutrition and tried to damage her mind because they were really into junk food,” explains Steve Hyman.

Hyman, a 26-year-old Health Project VISTA, has used other innovative methods to get the message of health nutrition across to a sometimes unsympathetic audience. He has produced two 30-second health spots on good nutrition which he calls “a little reflection while you boogie.” Hyman is a good example of what an accessible radio station can do for community members and vice versa. He says he first became involved in WVSP about four years ago after discovering the then-new station right in his hometown.

“I’ll never forget it,” he says. “I came to this little room here and I saw Chick Corea [the record album] laying on a table and I said, ‘Oh wow,’ because I was just beginning to cut my teeth on this kind of stuff.”

Hyman has stayed involved ever since, eventually learning “the board” — the production studio equipment — and hosting his own shows. Most of the other VISTAs and youth working in the Health Project have earned their FCC licenses and host various programs. Volunteers from as far as Durham and Greenville also produce several of the music shows that dominate the programming day. The station hopes to recruit more volunteer hosts and to continue to experiment with its mix of music; for example, it plans to expand the time devoted to blues, which always brings more listener requests than can be fulfilled in its present two-hour Sunday slot. The station’s music, especially its five to eight hours of jazz a day, has undoubtedly brought it most of its listeners and volunteers, but the bulk of the staffs time goes into producing the news and community features and administering the growing list of special projects.

In addition to the Health Project, a Media Project Against Crime has produced three illustrated booklets, a touring play featuring children and adults from the community, a videotape series on alternatives to prison, and a weekly radio show on crime problems and solutions. This project, funded by the U.S. Justice Department’s Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, indicates how the station has expanded into other media forms and how it relies on unusual sources for its operating funds. A recent matching grant from the Commerce Department’s Small Business Administration allowed the station to double its wattage from 50,000 to 100,000 — a move which should improve reception for listeners on its fringe areas, but which has also increased the monthly electric bill from about $500 to over $950. A pending grant from the Presbyterian Self-Help Development Fund will pay the salary of the station’s first fulltime engineer, and $9,000 from National Public Radio will support Jim Lee to produce nine half-hour programs on Cuban and Haitian refugees that will be distributed through the NPR network.

Georgia Collins says listeners now contribute about 10 percent of the total budget. She hopes to raise that to 60 percent by 1986 and also to convince area small businesses, especially black-owned companies, to underwrite specific programs in return for a mention of their name as WVSP supporters.

The station retains the nonprofit, worker-managed structure originally created in 1973, with a 10-member board governing the parent organization, Sound & Print United, Inc. Five people are elected by the station’s founders, two by the staff and three by the “members” — anyone who contributes $25 or 12 hours of work per year.

Over the years, the staff has found that advocating worker management was one thing, but sitting down and struggling over group decisions is a difficult learning process. “We had a lot of problems the first year,” admits Valeria Lee. “We simply didn’t know how to work as a collective. But we knew that to build something that advocated different ways of doing things, it was important to live it, to do it, to be it. And, you know, that’s been the only way we could have survived.”

“School prepares people for the job market by teaching them they have to have someone to tell them what to do,” says Jere King. “The good thing about WVSP is that no one tells you how to do anything. The problem comes when I cannot do something a certain way and the deadline is upon me. Then it’s the responsibility of the collective to have some input and say, ‘would this be helpful?’ or ‘should you try this?’”

Going beyond the established roles and empowering people to make decisions for themselves, with each other, is what WVSP is all about. Its possibilities as a community radio station are clearly unlimited. As Jim Lee asked in a speech to the National Black United Fund Conference on Public Policy and Economic Democracy last year: “How many microphones and tape recorders can be placed in a community or region? What happens when people realize that telephones contain microphones or that home tape recorders can produce radio programs?”

WVSP is a challenge — a direct challenge to the mystique of commercial and most non-commercial broadcasting, which claims that only certain people have the authority and the right to the microphone.

“Just how much of a threat to the status quo is an informed population? In our part of North Carolina,” says Jim Lee, “we are just beginning to find out.”

· For an article on the Assemblies, a network of black rural organizations in southern Virginia and northeast North Carolina, see Southern Exposure, Vol. VII, No. 1 (Spring, 1979).

Tags

Bill Adler

Bill Adler is an organizer with the Roanoke Rapids chapter of the Carolina Brown Lung Association. (1981)