Will He or Won’t He?

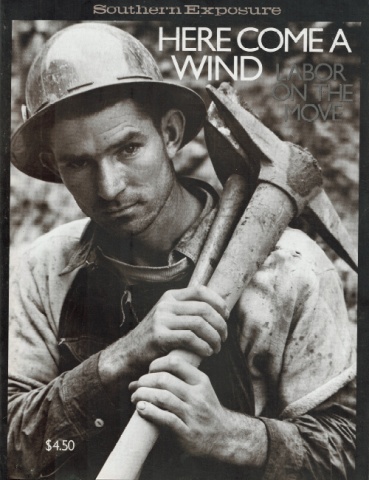

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 1/2, "Here Come a Wind." Find more from that issue here.

“I don't want them," snaps an Atlanta Steelworker when questioned about unions. "I do alright for myself and I don't need any union taking my money to settle somebody else's problem."

At the opposite extreme, a textile worker for J.P. Stevens & Co. explains that the same kind of stubborn individualism drove him to join the union. "The main thing I want," he says, "is my freedom of speech. Even if the union don't get us any money or benefits at all. I'd pay them dues just to know that I got my rights to speak in the mill without getting run out the door."

The difference between these two men illustrates the problem with typical generalizations about Southern white workers. Academics have concluded they are hopelessly racist, while many radicals embrace romantic stereotypes of plain, proud workers. Even blacks reflect the overall confusion. A Black Muslim factory worker, for instance, recently denounced the racism of whites who served with him in Vietnam. "But, man," he mused incongruously, "those Southerners were real men. When they get their minds made up to do something, they don't let anything stop them."

What is the true character of the Southern working man? What bearing do his basic values have on his attitudes toward unions? In considering such a ponderous and emotion-laden topic I have enlisted the aid of a previous student of the subject, Wilbur J. Cash, the noted journalist and agonizer of the Southern spirit. Though published in 1941, Cash's The Mind of the South is still the most accurate written account of white Southern wage earners. Many union and community organizers have read it and agree with its perceptions. The book has serious limitations, perhaps best expressed in an earlier Southern Exposure essay by Neill Herring, "The Constancy of Change" (Winter 1974). Cash, for instance, included only minimal reference to the female and black minds, and he spoke with a class bias that clearly revealed his "place in the world." But probably better than any other writer, he suggested answers to the questions that — 35 years after publication of The Mind of the South — we are still grappling with.

The Southern Mind

In his description of the Southern character, Cash emphasized the rigid adherence of all classes in the region to "the old brutal individualistic doctrine that every man was, in economics at any rate, absolutely responsible for himself, and that whatever he got in this world was exactly what he deserved." It might be argued that this rugged individualism is properly an American, rather than simply a Southern, trait. But Cash contended that it has left a particularly strong impress on the Southern character. He saw, in the economic dislocations following the Civil War and continuing into our own century, the preservation of primitive frontier conditions long after the region's physical frontier had been subdued. And, said Cash, "the essence of the frontier — any frontier — is competition" and the stern attitudes it evokes among the competitors.

Closely related to the white Southern worker's fierce individualism, according to Cash, is his extremely personalized view of the world: the certainty that any difficulty he faces is attributable purely to the meanness of the individual immediately confronting him. Cash felt that this personalization sprung from a lack of detachment, a nearly complete inability to stand back and analyze the social and economic forces affecting one's life — an inability, Cash might have added, to develop a sustained class consciousness.

Acting together, individualism and personalization would contribute to the development of another, more widely recognized trait of the Southern working man. For Cash, he "would be far too much concerned with bald, immediate, unsupported assertion of the ego...which was full of the chip-onthe- shoulder brag of a boy — one, in brief, of which the essence was the boast, voiced or not, on the part of every common Southerner, that he would knock hell out of whoever tried to cross him. . . being what they were, simple, direct, and immensely personal, conflict with them could only mean fisticuffs, the gouging ring, and knife and gun play."

Some will dismiss the notion of Southern violence as nothing more than just another paranoid stereotype. But in this case, the intuition and personal observation of Cash is corroborated by sophisticated public opinion research techniques. In his study. The Enduring South: Subcultural Persistence in Mass Society, University of North Carolina sociologist John Shelton Reed used a variety of statistical surveys to document the region's greater tolerance for private violence. For example, he found Southerners more likely to own guns and to favor corporal punishment in the schools. Union organizers verify that workers often release their frustrations with low wages and abysmal working conditions by beating each other up or by venting their anger on "socially accepted" targets, namely blacks and women.

When combined with individualism and personalization, private violence diverts Southern workers from considering an organized response to corporate injustices. "Historically, white Southerners do not think in terms of group problem-solving beyond the family," says Scott Hoyman, Southern regional director for the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA). "They're more inclined to think, 'If the boss doesn't treat me right, either I'll quit or I'll meet him outside the plant on Saturday night and beat the hell out of him.' This is changing today," continues Hoyman, who has been organizing Southern workers for 25 years, "but it's a starting point we can't afford to forget."

Cash was less equivocal: Southerners, he asserted, make bad union men. Their impetuous militance has triggered numerous spontaneous walkouts, but these have had "the character of unstudied mass action rather than of unionism"; they lack the consistency, discipline and long-range commitment which build permanent unions. "The Southern worker," wrote Cash, "is an impatient figure when it comes to paying dues to a union, wants to see swift and spectacular results, and is likely to fall away if he doesn't get them."

The Southern Mind Revisited

Despite his insightful descriptions, Cash's conclusions may be dated. He correctly identifies the chief characteristics of white working men, but he casts them in the negative context of the South's resistance to social change. I would argue that many of the traits, including individualism and personalization, are essentially neutral, rather than inherently evil or anti-union.

While the social and economic patterns of the Southern past have in fact reinforced their sinister potential, changing conditions like the influx of impersonal corporate employers and spread of unions might bring their more positive aspects to the fore.

Consider, for instance, what these developments have done to a good ol' boy like Jack Eudy. Eudy once seemed almost a caricature of the rugged individualist. "I don't need a union or anybody else to represent me," he said, "cause I'll struggle and make my own way."

Eudy, 34, took pride in the way he had worked his way up to a foreman's job at the Florida Steel Corporation's Charlotte, N.C. mill. He still speaks wistfully of an attention to detail and an insistence on quality. Yet he was liked by the men under him because of what Cash would consider a highly personalized way of looking at things. "I have a feeling for people," he says. "I like to get to know them and how they think. When a person came in in the morning, I could tell by looking at him whether he was going to have a good day or not."

Like many Southerners of his generation, Eudy was genuinely excited by the prospect of joining the newly expanded middle class created by the scores of flat, neatly-manicured industrial plants springing up all over the South. But his life was complicated in the spring of 1973 when organizers from the United Steel Workers of America (USW) began signing up his employees. With a union representation election scheduled, Florida Steel began firing union supporters.

"My instructions," says Eudy, "were to start building disciplinary cases against young people under 25 and against black people, because these are the easiest groups for the union to get to. My boss gave me a list of names and said, 'Something's got to be done. We don't want these people around when it comes time to vote.' And I said, 'What am I going to terminate them for?' He looked at me hard and said, 'That's up to you. You work with them eight hours a day. You find a reason. And if they don't give you a reason, invent one.'"

Eudy's highly personalized view of the world led him to fix the entire blame for the firing strategy on two local plant officials. He could not conceive that a removed, almost abstract entity like a corporation could plot something so "low-down."

Yet this outlook also produced another kind of reaction, one which Cash did not foresee. "Fighting the union didn't bother me back then," recalls Eudy. "That seemed like part of the job. The thing that really got to me was the tactics, having to fire people I knew were good workers. It kind of works hard on a man. It eats away at you on the inside." Then shifting to an analogy from the Vietnam War where he served, he continues, "You know, when you talk about war just in terms of two big political regimes fighting each other, people don't care much. But when you get down to the part where you're looking across the rice paddies, looking the man you're going to shoot in the eyes, then it gets on a personal level."

Eudy's individualism, which supported his fight to share in the South's new affluence, also shaped his response to the company's orders. "You always speak out when you know you're right," says a popular chewing tobacco commercial extolling the hardy virtues of the Southern working man. That characteristic compulsion to say what's on one's mind, and damn the consequences, proved Eudy's undoing. When he refused to fire a black worker with a large family, he was fired himself for having "a poor management attitude.” But he didn't stop there. He took a job as a production worker for Cannon Mills and became active in the TWUA organizing drive in Kannapolis. And he went to the National Labor Relations Board where his forthright testimony against Florida Steel brought the verdict that 12 employees had been illegally fired for their union activities.

Eudy's story clearly demonstrates that characteristics like individualism and personalization can cut both ways. Cash's complicated analysis of the baleful effects of the Southern working man's "puerile” tendency to personalize is quite convincing as far as it goes. But it was just such an inability to follow impersonal instructions that motivated Eudy's courageous act.

A New Day

Those who assume that Southerners are improved insofar as they are less Southern can learn from Jack Eudy. In fact, the best hope for unionism in the region may come from an appeal which joins the traditional values of the South — from stubbornness to personalization to a friendly openhandedness —with the progressive qualities of organized labor. At a time when gigantic impersonal corporations employ an increasing portion of the workforce, Eudy's determined resolve against dehumanized work relations and the J.P. Stevens worker's demand for free speech may demonstrate that Southerners have a special capacity for grasping the seeming paradox that lies at the core of trade unionism: a wage-earner's individuality is best asserted and protected through collectivity.

The difficulties involved in bringing large numbers of Southerners to this recognition cannot be overlooked. A George Wallace supporter-turned-union organizer echoes Cash's pessimism and points to one tendency among workers that has consistently been turned to their disadvantage. "Whenever I think about the Southern worker and my own efforts to organize him and change his thinking, I have a deep feeling of frustration and despair," he says. "They are determined to work against their own best interest because of a strong traditional identification with certain political and economic labels. There seems to be a willingness to accept the fact that they can only hope for a way of life that provides the bare necessities. They will continue to accept this, unless somebody tries to explain to them that it doesn't have to be that way, even at the risk of being called a radical or a race traitor."

Overcoming name-calling has been a constant problem to those who would unite the workers' interests. And the demagogue's special weapon has been the divisive tool of racism, dividing one group of workers against another and forcing them to settle, as the organizer says, for fewer rights and privileges instead of demanding more. As Cash pointed out in his typically florid style, the special appeal of demagogues to Southerners came from their brilliant use of rhetoric, their ability to exude "bluster and gasconade" and exhibit "great skill in using high histrionic gifts to body forth the whole bold, dashing, hell-of-a-fellow complex..."

But oratorical skills, the ability to project concern for people's problems and the capacity to get them to identify with one's self are not pernicious things in themselves. Again, they are neutral skills which have most often been used against workers' interest, but which might hold potential for the future. Organizers and modern-day populists will be successful in the South not only to the degree that their proposed programs meet people's real needs, but also to the degree that they are able to cultivate an inspiring style which brings traditional enemies together.

Few have understood the importance of rhetoric better than George Corley Wallace. "Wallace's speeches of several years ago are recorded in our minds and hearts," says the organizer. "There's a small part of me that still loves the man, even though I realize now that he's manipulated and used us. It's difficult to put into words why we like Wallace so much, but I think it has something to do with the fact that he was the first to articulate working people's grievances, before it became fashionable, and many of my people will vote for him for that reason alone."

Although stark realism forbids an unbound optimism about the swift organization of Southern workers, several recent developments give cause for hope that the positive side of traditional traits is gaining ground. A new generation of workers has entered the South's industrial workforce. "Young people are smarter today," says Jack Eudy. "They're taught about unions in school. They see on TV where people in Detroit are making five and six dollars an hour, and they say, 'Why can't we earn that much down here?' " Civil rights legislation passed in the '60s has brought another generally pro-union group into the Southern workplace. "Most blacks have already learned to think in collective terms before the union comes to town," says TWUA's Hoyman. "They've learned they can make certain minimal improvements in their lives by getting together and organizing." Blacks today constitute about 30 percent of the workforce in many textile mills. Finally, white people's general acceptance of their new black co-workers and the proliferation of integrated locals in the South represents one of the most hopeful — and unreported — news developments in recent years.

But in the final analysis, the outcome of the struggle to organize the unorganized may depend far less on the character of the Southern working people than on external factors over which they have little control. Companies like J.P. Stevens continue to use outrageous, illegal tactics against union sympathizers, while the NLRB and other government agencies hand out inadequate penalties. Congress ignores the need to strengthen the National Labor Relations Act to protect the rights of pro-union workers. And the American labor movement, after several notable failures, has been hesitant to commit the manpower and money required for Southern organizing efforts. Combined, these factors may determine, as much as any feelings held by the workers, whether or not Southerners get the chance to prove they can be loyal and conscientious union members.

Tags

Ed McConville

Ed McConville is a free-lance writer who has also worked in the South as a union and community organizer. He is at present writing a book on the struggle to organize J. P. Stevens Company. (1978)

Ed McConville is a freelance journalist who has written articles on Southern workers for a number of publications including the Nation, Progressive, and Washington Post. (1976)