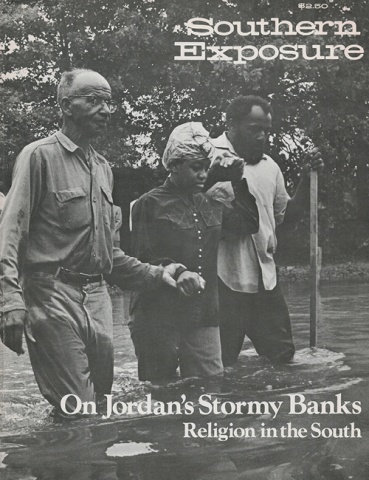

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 4 No. 3, "On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South." Find more from that issue here.

When I was nineteen years old, I joined the Air Force, mainly because my one year of college had been less than satisfying and 1 had absolutely no idea of what else to do. The education that I gained during the next four years changed my attitudes about a great many things. In truth, it was my first extended encounter with the world outside the mountains of Appalachia. 1 found quickly that my life had been very different from my fellow airmen.

It was the first time I was ever offended by the use of the word “hillbilly.” At least I was not alone. A friend from high school had joined with me, and even though they probably didn’t deserve it, two other young men were labeled hillbillies because they were from Arkansas.

When you join the Air Force, they issue identification tags that you are expected to keep on your person at all times until you leave the service. 1 thought the process of obtaining “dog tags” would be the easiest thing 1 had thus far encountered during my brief military career. A young sergeant sat behind a metal stamping machine, a complicated version of the bus station model. I handed him a piece of paper with my name, newly-assigned serial number, blood type and religious preference — the latter two are required in case you are wounded and need blood, a minister, or both. We had no trouble until we got to religious preference.

“Old Regular Baptist.”

“What’s this?”

“Sir?”

“What the hell is this Old Regular Baptist?”

“It’s the church I go to, sir.”

“Where the hell are you from, boy?”

“Southwest Virginia.”

“Oh, West Virginia.”

“No sir, Virginia, the southwestern part.”

“If you’re from Virginia, then say you’re from Virginia and if you’re a Baptist, then say you’re a Baptist. Don’t give me all this crap about southwest and Old Regular. Are you a Baptist or not?”

“Yes sir, I guess I am.”

I rationalized the encounter by feeling sorry for a man who had to spend his days sitting behind a machine stamping out little metal tags. Still, I was disturbed by his attitude, and was immediately defensive. The Old Regular Baptist Church was the only church I had ever known.

After several weeks, it was decided that we would all go to church on Sunday. It was, in fact, part of our training schedule; we were divided by denomination and marched off to church. By that time, I had been further defined out of the general category of Baptist and into the much broader category of Protestant. Even my Arkansas friends knew when to stand and when to sit, when to repeat lines or when to be silent. I bobbed up and down, mumbled words and followed as closely as possible the actions of everyone else. The closest I came to prayer was my fervent wish for the service to end.

It was a confusing time for me. One of the more disturbing aspects of the experience, however, hinged on an area that was somewhat of a surprise. Although I had always attended church, 1 had never considered myself a religious person. Only once before had I seriously questioned my feelings about the matter. While lying in bed with a pillow tucked up under my side to relieve the pain of a brand new appendectomy, I had been easily cornered by an evangelical preacher who wanted to know if I were a Christian. When I answered an honest “no,” according to my own definition, he immediately promised I was bound for hell. Since I thought I was going to die anyway, I did some thinking about my religious convictions. Two days later, however, these thoughts had subsided with the pain.

Now I was discovering that this minister was not the only one who had no way of knowing what I meant by being a Christian.

The Old Regular Baptist Church was once the center of Appalachian community life. Stressing the need to establish unity and cooperation among its own members and to act as a working example of harmony, its influence extended into the broader community. Today, the church still clings tenaciously to its religious traditions and to its own view of the spirit of Christianity and the Word of God. Yet in an age of massive cultural and technological advancement, it is often viewed as a unique sect of backwoods Christians with neither the mentality nor the spirit to survive. But to me, this church, which embodies the spirit of unity, cooperation, harmony and fellowship, is the very essence of Christianity.

The denomination traces its history back to the internal splits between the Arminians, the Calvinists, and Revivalists. There is no national organization and no one designated spokesman. Each church is separate and independent. Churches in a several county area form their own association and annually elect one elder as moderator, the religious and spiritual leader of the entire association.

Although I had always attended the Old Regular Baptist Church, I was never a member. Only those people who have been baptized are considered members; the rest of the community is the congregation. Church seats are arranged accordingly. Covering nearly a third of the floor space is a raised platform for preachers and members. The congregation sits behind and below them on a long bench seats arranged in typical church fashion. Women and men sit separately.

The Old Regulars’ belief in the great magnitude and responsibility of being a church member and the importance of the individual’s decision to receive God into his total life outweighs their desire to swell the ranks of the church. There is no pressure from church members to stimulate others in the community to join. There are no revivals and no membership drives; no undue influence is brought on family and friends. My great grandfather, J. C. Swindall, was moderator of the Union Association of southwest Virginia and East Kentucky for 42 years, yet only three of his nine children joined the church and they did so only after they were married with families of their own.

After each meeting, the closing minister opens the church for new members. Any person who has reached the “age of accountability,” usually 14 or 15, may come forward and express their desire to join the church. Usually the prospective member will relate how he or she has come to this deccision. It is obvious that the deliberation has been careful and long and, in many cases, related to a personal religious experience.

Any dissent from a church member can keep the prospective member from being received into the church. However, the person who raised the question must be prepared to defend his reservations with church doctrine. There is usually no question of acceptance, and a time and place is set for baptism.

The Old Regulars baptize by total immersion, usually in a stream or river near a church. One of the more interesting by-products of strip-mining in Appalachia is the difficulty the church now has in finding unpolluted streams or rivers for their baptisms.

Baptism is one immersion in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. As the new member wades from the water into the arms of family and other church members, he is greeted by glorious shouting and singing.

Members retain lifetime membership in the church where they are baptized, but may transfer without rebaptism to a new church with a letter of recognition from the old. Any member of another denomination must be rebaptized into the old Regular. “Backsliders,” as my granny called them, can re-establish church membership if they show proper signs of repentance for their wayward actions and upon examination can convince the other members of their desire to return to church.

Church services follow closely the schedules of the old days when preachers were scarce in a communty, and services were held on alternate weekends. ‘The furnishings of the church are bare necessities. The front wall usually contains pictures of beloved elders who have contributed their life to the church; inspirational pictures and wall plaques may hang there as well. There is a communal water bucket and dipper. Children often wander from the lap of a relative on the stand to the parent who sits with the congregation and anyone may come and go at will during the service. This is in no way considered a breach of etiquette. Only the very new churches have indoor toilets and many still do not have central heating. Air conditioners are almost non-existent, so many local businessmen still pass out fans with a picture of Jesus on one side and an advertisement on the other.

Each church has an Elder who serves as Moderator and primary preacher, although any preacher in full fellowship may preach also. Elders in the Church are treated with great respect. They are not trained and educated for the ministry, but are “called,” their abilities derived from the power of God.

New elders must be baptized church members and must receive sanction from other preachers within his church to take on the role. After a trial period to test speaking ability and knowledge of the Scriptures, which may last from a few months to a year, a special presbytery of church members is appointed to further question the candidate. If all members of the group are in agreement, an elder then “lays” hands upon the Brother and ordains him. Elders receive no pay and, unless they are retired, work at a regular job, assuming all costs of their ministerial duties.

Although some have inferred that the preachers’ sermons are random rambling loosely based on the Bible, specific biblical texts are chosen and carried through to conclusion. Since several preachers may preach on any given day and the order is determined just prior to the beginning of service, an idea may be abandoned if another minister delivers his sermon on that text. Sermons are not written and the Old Regular minister must rely heavily on his knowledge of the Bible and “a double portion of the Sweet Spirit” to get him through. It is not uncommon for a preacher who flounders to be “sung down” by the members. They may also be sung down if they tend toward long-windedness, for Old Regular services are uncommonly long even in normal circumstances.

There is no way to relate the emotional impact of Old Regular Baptist singing. There is no music but the voice. The songs are “lined,” sung by one person and then repeated by the group. This practice comes from a time when there was a shortage of songbooks and from the fact that the melodies, which do not follow standard notation, have depended on the oral tradition for their continuation. The melodies are closely “modal” and are hard to follow using the standard scale of music. Without drastic changes they cannot be translated for musical accompaniment. Although there are now abundant songbooks, they contain only words, no music.

The songs maintain the “long meter” tradition with great emphasis on feeling rather than rhythm. To some, the sound is melancholy and mournful; for others, it is a glimpse into the very soul of man. Some people, in their uneasiness, try to deal with it by laughing or total silence, but no one can ignore it.

It is common for people who like to sing to exchange songs they learned in church, and I am often asked to sing some of mine. Though I understand their interest, I cannot bring myself to do it. In many cases, the words are familiar because the Old Regulars simply adopt any song they like. The delivery, however, is a different matter. The first time I heard “Amazing Grace” outside of church, I believed it to be a popularized rendition of an Old Regular Baptist hymn. It is deeply satisfying to sing these songs, but at the same time, it calls for deep reflection in order to approach their true quality.

In their practice of the sacraments, the Old Regular Baptists interpret literally the words of the Bible. The bread is unleavened, usually baked by the wife of the deacon. The wine may be real or it may be grape juice. Women partake of the bread and wine separately from the men. Each takes a small bite and a swallow of wine and passes it to the next person until all have shared.

As the singing continues, the deacons and usually their wives prepare basins of water and towels for the foot washing. One by one the Brethren and Sisters kneel and wash each other’s feet, drying them with a towel which hangs from the waist. Here, vanity is cast aside, and their faces reflect the great joy in the humbleness of this act. Memorial services are scheduled on a yearly basis. In my memory this date has never changed. I know that wherever I am, on the third Saturday and Sunday of July, memorial services for my great-grandfather and other members of my family and community will be held.

Memorial services were the first church services I ever attended. My mother and father took me to the graveyard where we sat in an open shed built of skinned poles and a tin roof. The structure was built on the slope of a hillside and the seats, made of rough boards nailed to small poles, rose gradually with the hill, so that everyone could look down upon the platform in front which serves as a stand for the preachers and members. Many structures such as this are still used yearly in Appalachia.

Memorial services are a time of great excitement and joy as well as remembrance. For some, it serves as an annual reunion. Hospitality and community spirit run high; cooking may go on for weeks prior to the meeting.

Saturday is a warm-up day, with services at the church. On Sunday, everyone gathers on the hillside, dressed in their finest, be it a new pair of overalls or black patent slippers. As the last prayer ends, the somber air is instantly transformed with shouts of “Ever’body who’ll go home with me is welcome.” People from the community, especially families of the deceased, are expected to ask everyone in sight.

I had a great-uncle whose name was Columbus, though everyone called him “Burrhead.” It was said that he sold moonshine, and memorial time was about the only time he attended church. His wife had been dead for many years and he lived a bare existence. Yet each year his voice was first and loudest, “Ever’body who’ll go home with me is welcome.” Everyone knew that it was doubtful he had anything prepared, but everyone also knew he would share whatever he had.

I remember a conversation my Dad had with him which was repeated almost yearly by someone. “Why don’t you come on down to the house and eat with us. You can save your food and eat it next week. It’ll keep.”

“Well, I believe you’ve talked me right into it,” he said with a laugh.

Though there have been drastic changes in the life styles of many Appalachian communities, the Church still plays an important role in the attitudes of the people. In their efforts to exemplify the teachings of Christ, members and Elders lend strength and assurance to those around them. Their deep personal commitment is felt but never intrudes.

As long as I can remember , there have been black preachers and members in the Old Regulars. I think it is important to point out that while this country has labored under the burden of continued racial strife, this Church has maintained the equality of people as a natural part of the Christian ethic, not as defined by the legal limits of a person’s civil rights.

The Old Regulars also believe that the church must exist with total harmony among members. Each person must carefully search his heart and mind and there must be full harmony for the services to begin. Any dissent must be voiced with the full recognition that the unity of the church is broken, the most grievous state which can exist; but to stifle a question one feels should be asked is just as harmful.

Even today, there is a cooperative spirit among people in the communities of Appalachia that has its roots deep in the historical development of the region and, I believe, in the development of the Church.

As long as there are people who have taken part in the Old Regular Baptist experience, it will never die. I will most surely carry a part of it with me for as long as I live. With the great Appalachian out-migration, the church has now spread from the hills of east Kentucky and southwest Virginia to the cities of the North. Like me, many younger people are confronted with the dilemma of being part of two worlds. I call on my mountain roots for strength and security, but I live in a society that demands a more complex attitude for survival. 1 am still surprised at the effect the Old Regular Baptist church has on my attitudes, and the intensity with which I recall the things I saw and heard at church services. The memories may be clouded with childhood innocence, but my intellectual attitude cannot break my emotional ties. A part of me refuses to be totally swept up by a culture that has long forgotten the values that I have taken for granted most of my life.

Tags

Ron Short

Ron Short grew up in the Old Regular Baptist Church in southwest Virginia. He is on the staff of the Highlander Research and Education Center and is editor of Highlander Reports. (1976)