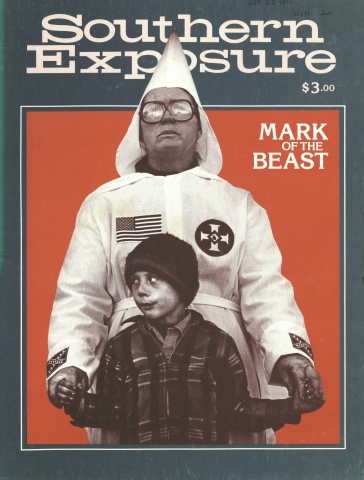

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 2, "Mark of the Beast." Find more from that issue here.

News Item

Poem by John Beecher, 1942

I see in the paper this morning

where a guy in Gadsden Alabama

by the name of John House

who was organizing rubber workers in a lawful union

against the wishes of the Goodyear Rubber Company

and the Sheriff of Etowah County

was given a blood transfusion

after being beaten with blackjacks

by five parties unknown.

The Police Chief is “investigating”

and I have a pretty good idea of what that will amount to.

A few years ago they took Sherman Dalrymple

President of the United Rubber Workers of America

out of a peaceable union meeting in Gadsden

and right in front of the Etowah County court house

before the eyes of hundreds including the Sheriff

the deputies

beat him almost to death.

Plenty more

who have tried to organize workers in Etowah County

have had the same thing happen to them.

The Government of the United States

should know about John House

but maybe they won’t notice the little item

on the back pages of the Birmingham paper

because the front pages are all filled up with Hitler

and how he is threatening democracy

so I am asking

the Government of the United States

to pay a little attention to this.

To defend democracy

the Government of the United States

is building a lot of munitions plants around the country

with the people’s money

because the people want democracy defended

One of these plants is being built at Gadsden

in Etowah County Alabama —

twenty four million dollars worth of plant to be exact —

twenty four million dollars of the people’s money

going into a county

which isn’t even a part of the United States

Or is it?

I think it would be a good idea

for the Government of the United States

to look into this

and see if they can’t persuade Etowah

to come back in the Union

If persuasion won’t work they might try a little coercion

because the laws of the United States ought to be made

good

and as luck would have it

there’s a great big army camp at Anniston

just thirty miles away

Not long ago I drove through this camp

and I saw new barracks and tents all over the scenery

and thousands upon thousands of soldiers

getting ready to defend democracy

They looked to me

as if they could do it

and they looked to me

as if they wanted a try at it

Maybe they could get a little practice over in Etowah

before they pitch into

the foreign fascists

When John Beecher wrote the poem below in 1942, labor organizers risked their lives to bring the message of economic democracy to some towns in the South. Today, brass knuckles have given way to a new breed of professional union busters who carry briefcases and know how to walk along the fine edge of the law. They are masters at using the National Labor Relations Act and its loopholes to cajole workers and tie up their union adversaries in endless court battles. They hide behind sanitized, impersonal claims of “maintaining an environment of open communication between employee and employer” for the sake of “industrial harmony and mutual prosperity.”

Yet for many workers in the South and across America, the tactics employed by this new breed of professionals are as effective and personally threatening as any beating delivered by an Alabama mob. “You still get sheriffs scaring people away during an organizing drive,” says Harold Mclver, Organization Director of the AFLCIO’s Industrial Union Department, “but the biggest headache now is these damned lawyers and their consultants.”

Consider these cases, for example:

· In Laurel, Mississippi, women who earn slightly more than the minimum wage for cutting up five chickens a minute for Sanderson Farms went on strike in February, 1979. “Little Joe” Sanderson, grandson of the poultry firm’s founder, allowed only three bathroom breaks a week, docked workers a day’s pay if they were six minutes late for work, made them operate cutting machines without safety guards, and arbitrarily transferred, fired or promoted “my people” without regard for seniority. When the mostly black women and their union, the International Chemical Workers, demanded better conditions and wages, Sanderson hired a New Orleans anti-union law firm: Kullman, Lang, Inman and Bee.

The law firm proved especially effective when the resulting strike spread to a petition drive for a union election at Sanderson’s nearby Hazlehurst plant. Anti-union letters and leaflets barraged workers with carefully phrased threats (for example, your plant may close, rather than your plant will close, if a union wins) that violate the spirit though not the letter of the law. If the union comes in, one pamphlet said, “You could lose some of your present benefits, your pay could be cut, your job could be eliminated. . . .” Another featured a picture of a black worker with the caption, “I’m voting No union for my family and myself. I’m voting No dues, No fines, No violence, NO UNION!” The union lost the election at Hazlehurst by a vote of 101 to 85; demoralized strikers at Laurel have begun trickling back to work, though a handful continue to hold out. (For other examples of anti-union tactics by attorneys Kullman, Lang, Inman and Bee, see the box below.)

· In Newport News, Virginia, 14,000 black and white workers at the largest shipyard in America finally lost their highly publicized strike in April, 1979. The defeat followed 11 weeks of police harassment and the legal ingenuity of Seyfarth, Shaw, Fairweather and Geraldson — the law firm hired by the shipyard’s owner, Tenneco, Inc. By a substantial margin, workers along the two miles of docks, warehouses and fabrication centers voted in January, 1978, to be represented by the United Steel Workers of America (USWA). “We need a union,” electrician Ronnie Webs, Jr., told Phil Wilayto of Southern Changes. “There’s a lot of safety hazards in that yard. The scaffolding we work on is dangerous. There’s no ventilation in the paint areas. We need a grievance procedure.”

Blacks, who comprise 40 percent of the workforce, had asked the Steel Workers to help organize Newport News in late 1976 because they felt it would take a big union to tackle the mammoth Tenneco, the nation’s nineteenth largest industrial corporation. They were right. Tenneco proved its toughness by adopting a new strategy — the “management” strike — which has become the trademark of its legal advisors. The Chicago-based law firm sells a 300-page “Strike Planning Manual,” and its tactics worked like a charm against the Newport News workers. By refusing to recognize the USWA’s election victory, the company forced the union to call a strike; lawyers from Seyfarth, Shaw then delayed settlement of the strike with clever legal maneuvers that contested the union’s bargaining rights. Disheartened by the prospect of long court delays, workers began crossing the picket line in increasing numbers, up to 30 to 40 percent by the end. USWA president Lloyd McBride finally confessed it might have been a “tactical blunder” to call the strike as a “test for organizing the South.” Eyeing the dwindling strike fund and diminished rank-and-file support, he announced that the strike would be “suspended” until the legal battles ended. After a total of 23 months of litigation, the courts ruled invalid Tenneco’s refusal to recognize the union’s election victory. Finally, on March 31,1980, the Steel Workers and Tenneco signed their first contract, but the union will have a hard time regenerating the solidarity lost during the Seyfarth, Shaw-inspired “strike.”

· In Durham, North Carolina, the liberal Duke University hired a team from Modern Management Methods to snuff out the flames of unionism at the school’s huge hospital complex. They were “communications experts,” explained Richard Jackson, head of personnel at the Medical Center. “Their function was to educate our supervisors in the best ways to communicate to the employees the many good things that Duke was doing and to counter, by legal means, the arguments of the union.” In fact, the $500- to-$700-per-day consultants from “3M” subtly engineered a vicious campaign of rumors, threats and intimidation that reversed the pleasant relations between administration and union which had characterized the early stages of AFSCME’s organizing drive.

Through a crash program of personal interviews and group seminars, 3M cajoled supervisors into becoming frontline advocates for management’s newly articulated anti-unionism, and trained them in the use of various key phrases designed to fuel anxiety among Duke’s 2,100 hospital employees. The campaign worked. Workers became fearful of discussing unions on the job and began to worry about how secure their jobs would be if they were identified as AFSCME supporters.

“Oh Lord, the rumors they were spreading around were unreal,” says one pro-union employee. “Supervisors told the people if they went with the union they might lose their jobs whenever someone with more seniority wanted it. They were told that the first thing the union will do is go on strike, and you’ll never get another job, and you won’t get unemployment, and you won’t get food stamps. People were scared to death. People would come up to me and say, ‘I think this is a good thing, but I can’t talk to you.’”

On February 16, 1979, the hospital workers voted 995 to 761 to reject AFSCME.

From election manipulation to stonewalling the bargaining process to sabotage of union contract renewals, these three campaigns illustrate the pervasive and pernicious use of attorneys in every phase of modern management-labor relations. With the help of attorneys like Kullman, Lang and consultants like 3M’s Raymond Mickus, corporations are increasingly determining the outcome of each of these phases in labor relations. Nationally, unions won only 46 percent of the representation elections held in fiscal 1978 (it was 57 percent 10 years ago); and they have watched the number of annual decertification elections swell from 239 a decade ago to 807 today, with unions losing threefourths of them. Back in the ’40s, when John Beecher wrote his poem, unions won over 80 percent of their elections, and by the end of World War II represented nearly 36 percent of the non-agricultural workers in the nation, compared with 23.6 percent in 1978.

Lawyers and right-wing consultants are not the only reason unions are losing ground nationally and barely keeping up with the expanding number of industrial and service jobs in the South. Economic instability, traditional reluctance among Southern white workers to join organizations, and the failure of union hierarchies to take risks, adopt innovative strategies or commit substantial funds to organizing all hurt. But the increased boldness of national corporations like Tenneco and liberal employers like Duke University to assert anti-union positions has crippled labor’s old style of organizing. Instead of holding its own in the North while gaining contracts with national companies who move South, labor now finds the Southern bosses’ strategy of “fight em tooth ’n nail” spreading across the nation. As Alan Kistler, director of field services and organization for the AFL-CIO, says about the proliferation of anti-union lawyers, consultants and right-wing lobbies, “They are creating a Frankenstein monster that is doing damage to the entire fabric of labor-management relations.”

On the national level, the Business Roundtable — composed of such old-line unionized and supposedly forward-thinking corporations as U.S. Steel, General Electric, DuPont and General Motors — recently joined forces with a hodgepodge of right-wing committees, led by Robert Thompson (J.P. Stevens’ Greenville, South Carolina, attorney) to smash the union-backed 1979 Labor Law Reform Bill. With this defeat of the proposed changes in the National Labor Relations Act, which included stiffer and swifter penalties for violators, the legal protections of workers’ right to free speech, petition and assembly remain shamefully inadequate. Companies can save themselves the cost of a union contract by simply breaking the law — threatening or firing their pro-union workers — and then paying a relatively small fine. This situation is frustrating not only to unions but to many judges. After reviewing the frequency with which corporations ignore the rulings of the NLRB, an Appeals Court judge declared, “It raises grave doubts about the ability of the courts to make the provisions of the federal labor law work in the face of persistent violations.”

On a state level, labor suffers the handicap of “right to work” laws (every state in the old Confederacy has them), which are kept in place by the organized right wing and the corporate elite. The laws prohibit the closed shop, and encourage the freeloader, workers in an organized plant need not pay union dues to get the same benefits as union members. While the laws inevitably erode the union’s membership and weaken its bargaining strength, supporters successfully appeal to the white Southerner’s general belief in “freedom of choice.” A host of state-level employer associations, business lobbies and conservative organizations also capitalize on the rhetoric of state’s rights and the conservative impulse against “outside interference” to keep labor on the defensive. There are now even conservative black consultants who, for a fee, instruct companies on how to improve their image in the black community and persuade black workers to vote against labor organizations (see box page 32).

On a local level, labor faces the growing specter of two-fisted attacks from any company it attempts to organize. For example, when the United Steel Workers began organizing Clark Equipment’s runaway plant in Richmond County, North Carolina, in 1977, they fell victim to Modern Management Methods’ precision training of supervisors inside the plant and an assortment of good-ole-boy anti-union tactics from Clark’s newly courted friends in the larger community.

To dissuade workers from visits and meetings, the Richmond County sheriff began parking his conspicuous Lincoln Continental outside the organizers’ motel rooms. The Chamber of Commerce of Rockingham had a motel clerk monitor their telephone calls. Police set up random road blocks near a bar owned by one of the pro-union workers, a man the company eventually fired. The husband of another pro-union worker was fired from his job at a local service station because “he was talking union.” And many others were threatened and told to vote against the union for the good of the community. The day before the election, the real estate agent who sold Clark the land for its plant took out a huge ad in the local newspaper, signing it only “Concerned Citizens of Richmond County.” It proclaimed:

Richmond County has lost numerous new industries because of the interest of unionism at Clark Equipment Company. . . . Please think of the position you were in before your employment at Clark. Richmond County needs new industries for continued growth. . . . Vote NO February 2.

Meanwhile, inside the plant, Modern Management instructed the supervisors and foremen to interview each worker, carefully noting their union sympathies. “The front-line supervisor is the best possible communicator in a campaign,” says Herbert Melnick, chairman of 3M. “He can talk to somebody without fear of breaking the law” — and he can be “easily fired” if he fails to do management’s bidding. Clark increased its supervisory personnel until the ratio of workers to supervisors dropped from 30-1 to 15-1. Beginning with those most loyal to the company, the supervisors conducted one-on-one interviews with workers, stressing the importance of the campaign to the individual’s job. Each day they reported their progress to 3M.

“The interrogation and pressure from supervisors was unbelievable and it ultimately turned the election against us,” says Mike Krivosh, the AFL-CIO organizer in charge of the campaign. “Modern Management stayed so far in the background, we never knew they were around. All we saw was a very polished pressure campaign to isolate and intimidate pro-union workers.” By the time the union realized 3M was behind the strategy, the union had lost the election 355 to 249.

The blatant instances of community interference — including the newspaper ad and sheriff’s harassment — ultimately led the NLRB to throw out the results of the February, 1978, election. The union also sued the sheriff and other business leaders for operating illegally as agents of the company in violating workers’ rights to support collective bargaining. The suit was dropped when the NLRB overturned the election, but, says Krivosh, “It effectively neutralized community interference in the second campaign. It became a fight between us and Clark.”

The pressure inside the plant during the second campaign remained intense. In the months following the first election, Clark hired 200 more workers who were screened for their union attitudes. Supervisors continued to call workers in for daily one-on-one “conferences.” Without any witness and separated from any support, each employee was grilled about work habits, job aspirations, family commitments, loyalty to the company and willingness to fight “outside threats” to his or her job. Meanwhile, the union organizers tried to keep up morale and build momentum in the departments where their committee members worked, hoping that the core of pro-union sentiment would influence less supportive workers. But the union’s second defeat — 409 to 391 — essentially reflected a difference between who controlled which department in the plant.

Clark gained a final edge by following a pattern often used by companies: it escalated its campaign in the days before the election, introducing a barrage of new arguments against the union. During the final 22 days, 26 pieces of Clark propaganda were sent to the homes of workers, posted on bulletin boards or distributed at the plant.

Later in this report we will review some of the techniques which consultants teach supervisors and personnel managers to use in screening, interviewing and influencing workers. But first we turn to an in-depth look at the anti-union propaganda which so often turns the tide and which remains a central tool in the attorneys’ and consultants’ bag of tricks.

MESSAGE OF FEAR

A detailed look at the vast network of anti-union forces stretching from Southern communities to the halls of Congress appropriately begins with the nuts and bolts of the union-busting campaign on the local level. Behind the dramatic and often crucial part played by community leaders like the county sheriff and Chamber of Commerce head, the core of a company’s day-to-day battle against a labor organizing drive involves a steady barrage of leaflets, letters, posters, speeches and special events.

The company’s propaganda attempts to personalize management’s power and draw the employee into the corporate “family” while reducing the union to those stereotypes which evoke the most fear and revulsion. Paradoxically, workers are made to feel both valued and expendable. They are wholly dependent on the company for their livelihood, but have an important role in deciding whether it will prosper and their job remain secure. Meanwhile, the union is portrayed as an alien organization with selfish interests set by outsiders which are divisive to the community’s harmony and ultimately lead to strikes, violence and loss of jobs.

With great finesse, the modern company’s attorneys and consultants design each form of communication to maximize the force of this message while narrowly avoiding an overt break with the law (e.g., by not specifically promising more money to workers if they vote against the union). And in the latter stages of a close campaign, they may even recommend conscious violations of the law in order to save the election. Some consultants, like Whiteford Blakeney, demand total control of a company’s propaganda — or accountability to only one or two top managers — so they can adjust the message to suit their reading of the campaign and the law. Other consultants take a less aggressive role, but still review all materials distributed by management and offer standardized letters or phrases for the company to follow.

Whiteford Blakeney’s propaganda illustrates several aspects of the appeal. The senior partner of the Charlotte, North Carolina, firm of Blakeney, Alexander and Machen, Blakeney is well known among union organizers. The wording, even the punctuation, of the “Blakeney letter” or “Blakeney notice” often do not change regardless of the particular company which signs it. Invariably, Blakeney plays on the themes of personal security and community harmony versus strikes and violence. Portions of the one sent by Perfect Fit Industries to its employees three weeks before an election are reproduced at the right.

Fear is probably the greatest weapon a company uses in its anti-union campaign. In addition to constant talk about job loss, company propaganda instills anxiety in workers by emphasizing “the uncertainty the union would bring into your future.” An atmosphere of disorder and potential chaos is heightened inside the plant with rumors, unexplained shifts of production or people and the presence of police or other authorities. Meanwhile, company literature presents workers with ugly images of union officials, contracts and rules. Collective bargaining, for example, is consistently pictured as a mysterious process by which “you can end up with less wages and benefits than you now have.” Similarly, all union dues are said to go directly to New York to “feed the coffers of union bureaucrats and fat cats.”

Among the most popular stereotypes used by the companies is that of the greedy union. It is an image that appeals not only to workers’ fears but also to their pocketbooks. Martin Marietta’s Sodeyco division successfully fought a drive by the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers in North Carolina with an elaborate booklet featuring the cartoon figure “Sam Sodeyco” spouting the company arguments. One two-page spread titled “High Paid Union Organizers” contained a list of OCAW staff, their salaries and expenses, with cartoon Sam saying, “109 OCAW representatives, plus directors, publicity people, clerks and analysts need your dues. . . .” On the next page, Sam complained, “In 1978, local OCAW members coughed up over 12 million dollars ($12,489,685.00) in per capita taxes. Plus another $213,544.00 in Employee Fees!”

A letter to employees of Dunlap Slacks in Dunlap, Tennessee, signed by three company officers, and written with the guidance of attorneys Bradley, Arant, Rose and White of Birmingham, Alabama, posed a series of weighted questions to drive home the company’s point about union greed:

Did the union tell you it has the right at any time to charge you fees and assessments in addition to monthly dues? Did the union bother to tell you that you could be forced to pay money in addition to monthly dues to support strikes in other parts of the country or to put money into the union treasury when it gets too tow? Did the union tell you that the International Union in New York City has over 280 employees and that those 280 employees are paid an average of over $35,000.00 each year by the union? Did the union tell you that it pays over 10 million dollars of your dues money each year in salaries to its officers and staff members in New York City?

The letter ended with fatherly advice: “I don’t like to see my friends taken advantage of by a group of outsiders who will say or do anything to get their money and give little or nothing in return. For this reason I urge you to vote NO on October 13.”

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters lost its election 23-to-2 against Walton Industries in Dallas after the company, on the advice of attorneys from Seay, Gwinn, Crawford, Mebus and Blakeney, called the workers together for a “captive audience” speech and dramatically stacked $4,200 in a pile to show how much they would collectively pay in dues. The following letter was sent out by the management of Donlin Sportswear of New Tazewell, Tennessee:

This union wants to take about $100.00 out of each of your paychecks each year, for union dues alone. It may also want to get additional money from you by INITIATION FEES, FINES, and ASSESSMENTS. This is the first, the most important, and the only reason the union is here. In only 10 years, the union can take ¼ of a million dollars from our employees in union dues alone. Each of us should understand that the union is not here to give anything away — it is here to take away. And the money that it hopes to take away comes out of your paychecks.

To dramatize the theme of false promises another favorite anti-union motif companies often pass out "Guarantee Forms" and tell workers to ask the union to sign. The one pictured here was used by National Steel Products in LaGrange, Georgia, with the advice of Atlanta attorneys Elarbee, Clark and Paul. It calls on the union to guarantee a wage increase following the election, and implies the threat of a strike by mockingly demanding that the union foot the workers’ bills during any work stoppage. Of course, it is illegal for the union to make such promises, but it may have trouble explaining that to workers.

Another popular device, distributed by the thousands in campaigns all across America, is the book of “Warranty Coupons.” “Protect yourself against the rash promises by some irresponsible organizers,” the coupon urges; a space is left for the union official to sign his name to such statements as: “I guarantee you will get a pay raise of an hour in the very first contract we get with your company.”

Lately, union organizers have turned the tables on management by passing out warranty coupons of their own — before the company gets a chance to pass out theirs. In a recent successful election campaign at the YKK Zipper Company in Macon, Georgia, an organizer with the Cement, Lime and Gypsum Workers International passed out a two-sided leaflet. On one side he listed guarantees the union could legally make and signed them; on the other side he listed several for management to sign: “If you will vote against the union, I promise and guarantee that — I’ll stop all harassment and get rid of all the petty work rules; — I’ll pay every worker the average wage that unionized workers in Macon, Georgia, now receive; — I’ll never again show favoritism to anyone in hiring, wages, job assignments and promotions. . . .”

Management uses dozens of other materials to undermine the image of labor unions — from Peanuts cartoon figures sticking out their tongues at union “trash” to stock booklets that tell ‘‘The True Story” to posters claiming, “The professional union organizing distortion will continue between now and the election.” Says James M. Miles of South Carolina’s anti-union law firm Haynsworth, Baldwin and Miles: “Of all the issues involved in a campaign, one issue, credibility, is absolutely critical to success. When the employee goes into the voting booth, the decision often comes down to the answer the employee gives to the following question: ‘Who should I believe, the company or the union?”’ Miles tells his clients — which included Clark Equipment in the campaigns discussed earlier — that “Every union statement or letter should be read carefully” and information in them should be contradicted “wherever possible.” In addition, the company should make special use of newspaper “articles depicting union insurance and pension fraud, fines, strikes and violence” to show that other authorities challenge the union’s credibility.

Without a doubt, however, the favorite theme in antiunion propaganda is the strike — long, costly, violent and disruptive - called by union outsiders and invariably leading to new workers replacing old. The message comes through letters, like this one sent to employees of South Carolina Electric Corporation.

We believe there is something vitally important to your future. The subject is “STRIKES”! Sometimes, unions and union pushers try to get people to believe that all they have to do is vote for the union and — as if by some wonderful type of magic — higher pay and better benefits and other changes in the operation of the plant will automatically result. We all know that this is simply not true!. . . The only thing the union could do to try to force the company to give into these demands would be to PULL YOU OUT ON STRIKE.

The destructive image of strikes also comes across in flyers and booklets, such as the two pictured here — one showing a series of newspaper articles with huge headlines about union violence; the other featuring a distraught woman with the caption “A Striker’s Wife Speaks Her Mind About the Cost of Strikes.” The inside of the second booklet displays a list of the companies and towns where the union in question went on strike, and the length of the strike; the company can buy quantities of the outside and print a list inside to match the union they are fighting.

Several anti-union consulting firms also supply companies with the “Strike Counter,” a device distributed to workers so they can calculate “what would a strike cost you.” By using a complicated table, the worker can compute the number of weeks of work “it would take to get back what you lost” by striking for a five or 10 cent hourly wage increase. The impact, in the midst of a heated union campaign, is to further confuse workers about the benefits of union membership.

More visual and straightforward anti-union literature projects the picture of pervasive strikes. For example, a two-sided flyer passed out by a Dyersburg, Tennessee, manufacturer of electrical equipment showed a map on one side dotted with miniature picket signs marking strikes by IBEW; on the other side was the warning, "Don’t Let the IBEW Put Dyersburg On the Map.”

In addition, companies use strikes as their strongest themes in captive audience speeches, slide shows and films. Perhaps the most bizarre and effective device used in recent months appeared in Salisbury, North Carolina, in a Fiber Industries’ offensive against Teamsters organizer Viki Saporta. A couple of days before the election, the company mailed a 20-minute record to each employee. The astounded workers listened to a War of the Worlds-style dramatization of a strike in their town, at their plant. The record opens with a radio show being interrupted by the emergency news that a strike has begun at Fiber Industries’ Salisbury plant. An on-the-scene reporter, describing the walkout in frantic tones, begins what becomes a tension-filled, “realistic” portrayal of a lengthy and bitter strike. The soundtrack includes interviews with anxious workers, several scenes of gunfire and fights between pro- and anti-union workers, and speeches by the sheriff, local ministers and the actual Salisbury plant manager — all denouncing the disruption of the community’s previous harmony. At the end of the record, the announcer explains that what you’ve just heard is based on an actual strike which occurred when the Teamsters tried to organize the Murray-Ohio Manufacturing Plant in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. “This dramatization is sent to you,” the announcer intones, “as just one example of what the Teamsters Union has done to employees and their families who put their trust in the Teamsters.”

The record capped a bitter campaign by Fiber which the Teamsters lost by a vote of 1,272 to 883. The NLRB later set aside the election results because of Fiber’s intimidating tactics — but the company succeeded in keeping the union out. “That record was the key to their campaign,” says Chris Scott of Teamsters Local 391. “It not only made strikes and violence a real threat, it also made it seem like 34 any worker who was pro-union would be betraying their community. And having the whole thing come across as scenes from a radio broadcast gave it legitimacy as a real event, something that could really happen.”

A year later, in the week before the new election was held, Fiber again sent a record to its employees. But this time the tactic backfired, and workers voted 1,002 to 990 for a Teamsters contract. “After the ‘79 experience,” says organizer Bill Grant, “it was an insult to the people’s intelligence” to send another record. Workers also refused to accept the plant manager’s promises of better conditions for a second time. “They [the company] started clamping down on us, and I know that made a lot of people mad,” employee Bobby Campbell says. “LeGrand [the plant manager] asked us to give him a chance, and I did in the first election — but not twice.”

Playing on the workers’ loyalty to community harmony and desire not to hurt their neighbors is another theme running throughout anti-union campaigns. The positive, paternalistic approach, which stresses the company’s commitment to the town and its employees’ welfare, is illustrated by this portion of a captive audience speech delivered by the manager of the West Jefferson furniture factory:

Now here's the main reason I called this meeting here this week. It’s because I’m upset, I’m disappointed that after all the years that we’ve worked together side by side suddenly our friends and neighbors who work here are ready to throw our good relationship out the window and turn to some stranger outside. Let’s look at what Thomasville Furniture Management has done. Sure things are not perfect here, but look how far we’ve come since 1964 when Thomasville Furniture Industries bought the plant. I was here then and so were some of you. I can remember the working conditions were very poor. Benefits was low. Thomasville Furniture Industries has put five million dollars in this plant, to make it a better place to work, and I think you all agree that this is the best place in Ashe County to work.

On the other hand, pressure tactics about the union’s harm to the community appear in ads like the one in Rockingham (p. 30) and the suggestion from attorney James Miles of Haynsworth, Baldwin & Miles that “business leaders and local government officials . . . contact the close friends and relatives of employees in the company which the union is attempting to organize and discuss with them the disadvantages of having a union in the community.”

An appeal to the worker’s individuality, “manhood” and self-pride ironically often accompanies these calls for greater citizenship and community loyalty. For example, in the same captive audience speech at West Jefferson, the plant manager chided the workers: “You don’t need a union organizer to come in here and speak to me for you. . . . You’ve always been able to talk for yourself as an individual. I sincerely hope that before you sign one of those union cards or support a union and give up your right to talk for yourself that you think real hard.” Other attorneys and consultants emphasize “the loss of individual freedom is a high cost to pay,” and soberly warn, “You should carefully consider whether you are willing to pay the bill of turning your right to speak for yourself over to the union.”

TEACHING THE TRADE

Thirty years ago, union busters learned their tactics through trial and error and from such boo ks as How to Meet the Challenge of the Union Organizer, written by Joseph Lawson, founder of the first anti-union consultant firm, SESCO (see box, page 41). Despite the reservoir of pre-designed leaflets, today’s union busters must still experiment with new tactics that capitalize on weaknesses in, or new rulings regarding, labor law enforcement. Today, the principal medium for learning the business is the management seminar. In a dozen or more cities each month, groups of 10 to 60 consultants, attorneys, personnel managers and other company officials pay $175 to $600 to learn the latest anti-union tactics. Much of the content of these seminars focuses on crass manipulations of labor law and the NLRB, but most of them adopt a public posture of offering clinical sounding lectures on “positive management” techniques.

Any management that gets a union deserves it — and they get the hind they deserve. No labor union has ever captured a group of employees without the full cooperation and encouragement of managers who create the need for unionization. Management language does not even have a positive word for operating non-union. The positive approach is: MAKE UNIONS UNNECESSARY.

So says Dr. Charles Hughes, an alumnus of “two of the most successful non-union companies in the country,” Texas Instruments and IBM. Hughes is probably the nation’s most popular lecturer on the art of fighting unions. He travels over 350,000 miles a year, appearing at anti-union symposia sponsored by two New York City firms - Executive Enterprises, Inc., and Advanced Management Research, Inc. (AMR). The two- or three-day seminars, in cities like Atlanta, Dallas, New Orleans and Houston, cost top executives $450 to $575, and they get a fact-filled pep talk on the techniques for keeping employees happy, productive and non-union.

Billed as “one of the best-known behavioral scientists working with industry,” Dr. Hughes teaches each class of executives how to use behavioral modification to keep employees away from unions. Workers are viewed as “loveable bears” who can be controlled by a “jelly bean” method of rewards and punishments. Hughes’ technique requires management to classify each employee by his/her value system, under such categories as “tribalistic,” “manipulative” and “conformist.” Dr. Hughes then advises management to use an assortment of “carrot and stick” favors and reprimands to bring the alienated, disaffected or lonely worker into the tribe. If these ploys fail, that worker will become a prime target for the union’s values.

Hughes’ brand of industrial psychology is increasingly imitated by consultants, lawyers and management teachers across the country. Labor Relations Associates, based in Houston, features a two-day “Union Organizing Game” (for $350 per player) which uses role-playing and group therapy techniques to emphasize that “supervisors must be trained in how to recognize and deal with the very early signs of union interest.” Fran Tarkenton, former Minnesota Vikings quarterback, set up Behavioral Systems, Inc. (BSI) in Atlanta to teach behavior modification techniques to supervisors and other management personnel. His firm’s 25 “management consultants” conduct intensive training programs stretching over months for companies ranging in size from J.P. Stevens (40,000 workers) to Alba-Waldensian in Valdese, North Carolina (1,500 employees). BSI also offers training on a crisis basis for companies “caught” in the midst of a union organizing drive.

A New Jersey outfit, Professional Seminars, Inc., which includes New Orleans, Atlanta and Dallas on its itinerary of two-day, $350-per-person seminars, also promotes the “preventive” method of “maintaining a non-union environment.” One of its principal lecturers is Raymond Mickus, executive vice president of Modern Management Methods, who claims involvement in over 1,000 union elections and bases his advice on his consultant firm’s credo: “We don’t believe workers vote for a union. Rather, they vote against management.”

The psychological approach in these behavior-modification programs actually recognizes the legitimacy of workers’ desire to join unions and accurately identifies its roots in a system of management insensitivity that goes deeper than a particular wage dispute or single grievance. But, perversely, the pop-psychologists of the seminars are determined to reject unions and the idea of workers’ collective power, and inevitably adopt hard-line anti-union advice in their own presentations. At Charles Hughes’ seminars sponsored by AMR, attorneys from the New York law firm of Jackson, Lewis, Schnitzler and Krupman follow the behavior analysis sessions with the nuts-and-bolts lessons of how to destroy a union campaign. Among the chief elements:

· Stall and delay when workers request a representative election. “Time is on the side of the employer,” the lawyer-instructor says.

· Fire workers who might be receptive to unionization. “Weed them 36 out. Get rid of anyone who’s not going to be a team player. And don’t wait eight or nine months. I’d like to have a dollar for every time there’s union organizing and the employer says, ‘I should have gotten rid of that bastard three months ago.’”

· Exclude groups of workers most sympathetic to unions from the proposed bargaining unit. And then “stack the deck” by adding new workers before the election.

· Use legal and illegal means, including threats, exaggerated promises and spying, to discourage workers from voting for the union. Even if you are caught by the NLRB, Raymond Mickus tells his seminars, ‘‘you have to put penalties for unfair labor practices in perspective.” Getting fined for firing a worker, or being ordered to post a sign saying the company will not commit any labor law violations in the future, is a cheap price to pay for defeating the union. Even if the election is set aside and a new one ordered, ‘‘You will probably win the second election,” says Mickus. And few unions try a third time. The advice from another Northern expert who regularly visits the South is even more explicit. At a recent seminar in Charlotte, North Carolina, sponsored by Wake Forest University, Woodruff Imberman of Chicago’s Imberman and DeForest consulting firm told a group of furniture, textile and other manufacturing executives:

It’s absolutely legal to scare the beejesus out of your female employees with threats of strikes, violence and picket lines, and I suggest to you that this is a very good way to scare the hell out of them.

Imberman recommended that companies hire more women because of their vulnerability to anti-union propaganda. ‘‘You have to give the females some idea of some input,” he said, and he advised creating the proper psychological climate by keeping the plant clean and maintaining “feminine bathrooms.” Imberman further suggested that companies establish their own grievance procedures not only to resolve complaints, but also to keep management in touch with its own weaknesses and to strengthen employee morale. From this progressive sounding advice (which several textile and furniture managers at his Wake Forest seminar pooh-poohed), Imberman slipped back to a cornerstone of union-busting: racism.

It is my strong finding that blacks tend to be more prone to unionization than whites. Now you have EEOC these days and you have to follow the EEOC laws and have whatever the percentage of blacks you are supposed to have. There is no reason for you to be heroes about this, and interested in abstract justice or upraising the downtrodden. So don't be heroes about the whole goddamn thing and fill up the work force with blacks. If you can keep them at a minimum you’re better off.

Then he added, “I feel the same way about Indians that I do blacks. . . . Stay the hell away from Puerto Ricans.” The goal, Charles Hughes said in another seminar, is “hiring beautiful people who do what they’re told” and who are so “programmed that the union can’t even communicate.”

Another old management tactic — the lockout — has taken on a new twist under the tutelage of lawyer-consultants from both North and South. Even if the union wins the election, “It doesn’t mean you have to sign an agreement,” Atlanta attorney McNeill Stokes told a group of building contractors at a Los Angeles seminar. A company can offer meaningless concessions at the bargaining table until the frustrated union either quits or calls a strike. If it doesn’t quit, “You goad them into a strike,” says Stokes, and then hire new workers.

At another meeting, this one sponsored by the Illinois Chamber of Commerce, the prime architect of the “management strike” spelled out illegal techniques to break a union. "If you say we say it, we didn’t say it,” warned attorney james Baird of the Chicago firm of Seyfarth, Shaw, Fairweather and Geraldson, which represented the Washington Post and Tenneco’s Newport News Drydock Company in their union battles (see page 28). “Off the record,” Baird discussed how a strike can weaken the union, create disenchantment among some of its members and open the door for the suggestion from management that a decertification election is possible. It is completely illegal for a company to promote an anti-union drive among its workers, but Baird detailed “how to set it up so the employee comes in and asks all the important questions on his own.”

At sessions like his Wake Forest seminar, Woodruff Imberman also promotes management’s illegal involvement in the “Vote No” committees and decertification elections. He tells the assembled executives to support the employee’s efforts by “slipping $20 bills in their pay envelopes” and by telling local merchants the company will make up the difference if they agree to charge the decertification committee only token amounts for printing and supplies. Significantly, Imberman’s co-instructor at the Wake Forest seminar was Robert Valois of Raleigh, the attorney representing the J.P. Stevens Employee Education Committee (see box, page 44). In his part of the seminar, Valois made it clear that managers should encourage workers to form pro-company committees and guide the direction of community support by keeping a “tight rein” on activities by other businessmen and “concerned citizens” ranging from the Ku Klux Klan to local ministers.

RIGHT-WING NET

Consultants like Bob Valois operate through an elaborate network of state, regional and national anti-union organizations. In contrast to the newer consultant firms and for-profit corporations, these organizations have roots deep in the older right-wing establishment and often perform other functions for the conservative businessmen they represent. For example, attorney Valois arranged for the non-profit North Carolina Fund for Individual Rights (NCFIR) to help raise money for his client, the Stevens Employee Education Committee. NCFIR sent out fundraising appeal letters over the name of Stevens employee Gene Patterson and in short order pumped $36,000 into Valois’ campaign to decertify the union in Roanoke Rapids. Since it is illegal for Stevens to support the activities of its anti-union employees, the NCFIR served as a convenient — and tax-exempt — conduit for contributions for other businessmen and company foundations, including those of Blue Bell, Chatham Mills and Deering-Milliken.

NCFIR was established in 1975 “to further the defense of the rights of individual men and women who are suffering legal injustices as a result of unlawful government action.” Union busting apparently falls within NCFIR’s idea of defending individual rights; suits by the non-profit group also contest the right of the University of North Carolina campus newspaper to endorse political candidates, and the UNC student legislature’s policy of allocating two of its 20 seats to blacks. Similar cases upholding “white rights” against minority hiring and admission policies make up the greater part of NCFIR’s docket.

The organization’s director is Hugh Joseph (“Joe”) Beard, Jr., a young Charlotte attorney active in Ronald Reagan’s campaign and the North Carolina Conservative Union. The president is Wilson J. Bryan, a sales manager for the staunchly anti-union Sodeyco division of Martin Marietta. Bryan speaks glowingly of the growth of NCFIR (it had an operating budget of $30,000 in 1978) and the “fantastic guys” in the state Republican Party, Conservative Union and Conservative Society who have made it go. Bryan himself was the first president of Charlotte’s Mecklenberg County Conservative Union, and he replaced NCFIR founding president Richard J. Bryan, who moved to Washington to serve as Jesse Helms’ Administrative Assistant. The right-wing links of NCFIR people are too numerous to list here, but it is noteworthy that union-buster Bob Valois’ law partner Tom Ellis has been the chief strategist behind Jesse Helms’ several campaigns and multitude of off-shoot organizations.

Another state-level non-profit organization sponsoring a host of anti-union, anti-black and other conservative causes is Frank Krieger’s Capital Associated Industries, Inc. (CAI). Bob Valois has worked through CAI on several occasions, but the Raleigh-based group differs from NCFIR in being a membership organization for employers in the eastern and central part of North Carolina. Member companies share a common labor pool, and CAI represents their interests through preaching the gospel of anti-unionism at civic clubs, promoting political candidates hostile to labor and attacking those with AFL-CIO endorsement, sponsoring union-busting seminars and distributing to members a “Confidential Bulletin” on labor trends and union activities in their area. While the association is chartered as a non-profit organization designed to “promote industrial development and . . . the friendly exchange of information among” its members, in fact much of its work borders on the illegal.

In 1974, for example, CAI president Frank Krieger helped the personnel manager of Rockwell’s Raleigh plant engineer a decertification election which ousted the International Association of Machinists (IAM). In apparent violation of labor law, Krieger helped an employee of Rockwell drum up support for the decertification campaign inside the plant. The personnel manager at Rockwell, Robert Click, also retained Krieger’s friend, union-buster Bob Valois, to file the decertification petition with the NLRB. On July 22, 1974, IAM was formally voted out by a margin of 136 to 74. Later Click left Rockwell and, with the help of Krieger’s network, became personnel manager of a Texfi Industries’ mill. When he left that position, he became a free-lance personnel consultant operating through Krieger’s CAL His experience with company-inspired anti-union workers’ committees quickly served him well, since his most important client soon became Valois’ J.P. Stevens Employee Education Committee in Roanoke Rapids (see interview with George Hood, page 44).

Capital Associated Industries belongs to a much larger network of conservative business organizations coordinated through the Washington-based National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). NAM represents 12,000 companies and 260 manufacturing trade associations. NAM is best known for its straightforward pro-business lobbying on Capitol Hill, but it is far more heavily dominated by the right wing, and more preoccupied with the anti-union crusade, than even the regular leaders of the business press may suspect. NAM directors include such John Birch Society council members as F.E. Masland and Ernest Swigart as well as National Right to Work Committee directors M. Merle Harrold and C. Neil Norgren.

NAM’s own “Strike Force for Business” is the National Industrial Council (formerly the Council for Industrial Defense), composed of about 150 member associations — like Capital Associated Industries — organized according to regional identity rather than type of product. Under a non-profit status, businesses in a given area pool their resources to fight state and local government regulation, promote right-to-work laws, oppose increases in workers’ compensation benefits and minimum wages and combat unions active within their geographic boundries. Others in the South, besides CAI, go by such names as the Georgia Business and Industry Association, the Texas Association of Business, Associated Industries of Alabama and the Tennessee Manufacturers Association.

North Carolina, one of the best organized states in the country, has five separate associations, each with a clearly defined territory: they are headquartered in Raleigh, Gastonia, High Point, Charlotte and Asheville. Frank Krieger’s counterpart in Charlotte, for example, is Edward J. Dowd, president of the Central Piedmont Employers Association, which represents about 350 area companies, making it the largest of the five NAM-affiliated “industrial relations groups” in the state. The membership list covers everything from metal fabricating plants to hospitals. Though born and educated in Massachusetts, Dowd has been Charlotte’s watchdog against unionism for 21 years.

Dowd’s office is spacious and tastefully furnished with couches and coffee tables, and he has a battery of secretaries to impede an intruder’s progress. Dowd has not had particularly good luck with reporters, and when asked recently about his duties as co-chairman of yet another NAMrelated anti-union vehicle, the Council for A Union Free Environment, he ordered the tape recorder off and said, “If I had known you wanted to talk about unions you wouldn’t have gotten in the front door. The unions have been trying to get something on me for years.”

Among other things, Dowd’s staff will conduct “attitude surveys” inside a member’s plant to diagnose employees’ morale problems and to pick out key workers for management to groom for “future positions of leadership” — or throw out as potential agitators. The “lack of contamination” in the South is a topic he is not reluctant to talk about, and the region’s “pure stock” who take their work seriously, have a low rate of absenteeism, and have limited North Carolina’s unions to a 6.9 percent slice of the work force — lowest in the nation — are a source of pride for him.

Over at the Dixie Village Shopping Center, R. Thurman Taylor, president of the six-county Associated Industries of Gastonia, is more forthcoming about the actual purpose of the organization. “Of course most of the companies coming into our area from the North are coming to escape unionism. And when they come in here, we tell them very frankly if you don’t come with the determination to stay un-organized we don’t want you. And if you do come, we want you to hire a Southern personnel man. And also, if you’re followed, as we fully expect you to be, we want to recommend a Southern labor relations attorney who understands the psychology of the Southern people. And they’re all buying that philosophy.”

The 175 companies which each pay $100 plus $2 per employee a year to be a member of the Association are pledged “to champion the free enterprise system, which is the American Way of Life ... to assist in the preservation of the largest measure of industrial freedom consistent with the rights of others . . . [and] to oppose undue encroachment of governmental authority on the Freedom of Industry, labor, individuals or groups.”

“Associated Industries, Inc., is more or less a policeman,” its brochure states. “Its work is a constant protection of the whole community, but like the police, it assists those who need help in specific problems.” Those include “securing information” on the rank and file, checking references for personnel departments, advising on “labor unrest” and generally fostering “an atmosphere in which profitable businesses can be encouraged.”

“Only two companies have been organized in this county,” Taylor says with pride, “and I don’t feel like they wouldn’t have been organized if they had listened to us.”

Ideology and militant anti-unionism also pervade material distributed by the Birmingham-based Associated Industries of Alabama. “You cannot maintain a non-union status with an attitude of indifference,” asserts a program brochure for a recent AlA-sponsored seminar. “A continuing vigilance, a periodic review of your policies and practices are necessary steps to retaining the important right to make unilateral judgements in the control of your business.” AIA president Gilbert Mobley joins Thurman Taylor, Ed Dowd and 75 other union busters on the board of something called the National Labor- Management Foundation.

The National Labor-Management Foundation is one of the oldest of the non-profit anti-union lobbying and propaganda groups operating independently from, but overlapping with, the sprawling NAM network. Now headquartered in Washington, it has been coordinating legislative efforts since 1947 for about 3,500 companies and employer associations against what it calls the “increasing arrogance of union officials in the use of their monopoly power in the economic and political arenas to exert control over governmental bodies.” For many years, the organization was relatively inactive, but it has taken on new life under the direction of a new president, S. Rayburn Watkins, who operates out of Louisville, where he is the president of the NAM-affiliated Associated Industries of Kentucky.

The National Right to Work Committee has harassed the labor movement since 1955. Created by Congressman Fred Hartley (of the Taft-Hartley Act) and a Virginia manufacturer and john Birch endorser, Edwin S. Dillard, the Committee continues to focus primarily on the preservation of open shop and “right-to-work” laws, with help from affiliated state committees and front groups like the Women Organized for Right to Work and the Citizens Committee to Preserve Taft- Hartley. It publishes a newsletter with a circulation of 175,000, about 150 press releases annually and the Right to Work Digest for about 7,000 legislators and local politicians; its films “And Women Must Weep” and “Springfield Gun” are widely used by companies to prove to their workers that unions lead to strikes and violence.

The organization rapidly expanded with the formation in 1968 of the taxexempt National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation (NRWLDF). The Foundation now raises millions each year from direct mail contributions, runs ads for workers allegedly victimized by unions and takes many publicity-worthy cases to court each year with its in-house staff of 15 lawyers. In 1976, the Committee created the Employers Right Campaign Committee to raise money for key conservative candidates. Today, the National Right to Work Committee and Foundation boast a staff of about 130 in spacious headquarters just outside Washington (Springfield, Virginia) and an annual income of over $9,000,000 — most of it raised through direct mail appeals.

Its board of directors features several prominent anti-union attorneys, including Whiteford Blakeney, the notorious North Carolina union buster who represented J.P. Stevens for years (see page 31). Jesse Helms’ chief strategist, Tom Ellis, has helped the NRTWC in the past through his law firm Maupin, Taylor and Ellis, and Helms himself has signed letters for the organization’s direct mail efforts.

Helms also serves on the advisory board of a similar non-profit outfit, Americans Against Union Control of Government (AAUCG), which is itself a division of Jim Martin’s Public Service Research Council. Reed Larson, president of NRTWC, helped Martin set up AAUCG in 1973 with a number of other right-wingers; it focuses its anti-labor program on opposing unionization or collective bargaining rights for public employees on municipal, state and federal levels. After six years, its annual budget already approaches $3.5 million, although much of that goes into the cost of more direct mail appeals.

Outside the NAM network, the most important association of unionbusting companies is the Nashville-based United States Industrial Council. The USIC, formerly known as the Southern States Industrial Council, was founded in 1933 when John Edgerton, a Tennessee textile magnate and former president of NAM, decided the South needed an ultra-conservative business organization to resist child labor laws and oppose the National Recovery Act’s goal of raising wages in the region. In order to reflect its expanding constituency, it became the United States Industrial Council in 1971. The Council now claims 4,600 corporate members drawn from every state, employing more than 3,000,000 American workers.

Edward J. Walsh, public affairs director for USIC, says many of these corporations also belong to NAM, but they support USIC because of its “principled stand for the free enterprise system.” Larger companies like GM and U.S. Steel may contribute as much as $10,000 annually, but Walsh declined to estimate the organization’s total budget. Eighteen of the 27 USIC executive members are still presidents or chairmen of Southern corporations, but Walsh is correct in noting that the hardline approach taken by the organization and its tax-exempt USIC Educational Foundation has attracted businessmen from every region.

The USIC takes positions on nearly everything: SALT II, pornography, the death penalty, encroaching socialism, the financing of education, the erosion of the middle^class, the price of welfare, the troubles of small business and, of course, the “monopoly power” of trade unions. USIC president Anthony Harrigan, a former Gannett newspaper reporter, authors many of the position papers, which are then printed by the thousands in pamphlet form and distributed as ideal “cheat sheets” for dinner speakers at Toastmasters and Rotary Clubs all over America. Member companies can purchase pamphlets in quantity at a discount and insert them in pay envelopes and executives’ mailboxes. Harrigan “is sensitive to the pulse of America,” Walsh says. “He travels all the time, rides all over the country, stopping in small towns and visiting with local businessmen, newspapermen, educators and ordinary people, getting the feel of what people are thinking out there in the ‘provinces.’ ” Twice a week Harrigan mails out his views on current events to 250 daily newspapers, and about 100 routinely use the column.

Harrigan takes a dim view of the “arrogant regimes of the Third World which have little capacity to create wealth on their own but a huge appetite for the wealth produced by a dozen generations of Americans,” and he calls on the United States to "maintain and widen the distance between the advanced and retarded nations.”

Of the last three booklets published by USIC, however, two deal with successful employer resistance to unions. (The third is an expose of "The Anti-Nuclear Movement” and the "burntout hippies” who command it.) One details how Chatham Manufacturing Company of Elkin, North Carolina, won a 23-year struggle with the textile workers union. The second recounts the story of the failing union drive at J.P. Stevens; it was purchased in bulk by the Stevens company, a USIC member. Other USIC anti-union pamphlets include: "An Employers’ Guide to Staying Non-Union,” "Excessive Union Power,” "Fighting for Free Enterprise” and "Unions Are Obsolete.” All hold to the basic theme that unions possess "intolerable privileges and immunities” which imperil America.

Through its Educational Foundation, the USIC tries to "broaden the younger generation’s understanding of the conservative philosophy.” The Foundation establishes "free enterprise study groups” on campuses, has a summer intern program for "young conservatives,” gives grants to "free enterprise scholars” and promotes national lecture tours of such wellknown conservatives as Michael Ivens, a British opponent of nationalization (1978), and Peter Clarke, a Scottish enemy of socialism (1979).

The USIC strongly supports the new "free enterprise” curricula being offered on some U.S. campuses, usually courtesy of an endowment by big business — for example, the Center for Private Enterprise Education at Harding College in Arkansas. The first private enterprise chair at a state university was created in Georgia, where such unionized but conservative corporate giants as the Georgia Power Company and Southern Bell had long been active in the USIC’s predecessor, the Southern States Industrial Council. Other businesses and universities are following the Georgia State University model. Kent State and the University of Akron each now have a Goodyear Professor of Free Enterprise, and the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga has a private enterprise chair bequeathed by a local attorney. It is the hope of the USIC that the days of the liberal educational establishment are numbered. By way of contrast, an attempt by unions and liberal educators to establish a Labor Education Center at North Carolina Central University in Durham, a branch of the University of North Carolina, was soundly crushed in 1978 through the efforts of a coalition of conservative and business interest groups.

The newest "non-profit” network threatening unions is an interrelated group of foundations which initiates conservative suits working on a combined budget of over $3 million. Begun in 1972 in California to defend Governor Ronald Reagan’s welfare cutbacks, the Pacific Legal Foundation and its backers — chiefly the Fluors of the Los Angeles construction-engineering combine, Fluor Corporation — moved eastward with what they considered a good idea. The Fluor Corporation itself bought up Daniel International of Greenville, South Carolina, a powerplant builder and one of the South’s top non-union general contractors. Meanwhile, the Foundation became the National Legal Center for Public Interest, opened headquarters in Washington under the direction of rightwing corporate attorney Leonard J. Theberge and set out to mirror Ralph Nader’s network with a string of regional foundations sponsoring court suits against minorities, women, the environment and labor. The Southeastern Legal Foundation is directed by former Republican Congressman Ben Blackburn and counts among its trustees the heads of Lenox Square, West Lumber Company, and Redfern Foods, all of Atlanta. The office was funded with $25,000 "seed money” from the National Legal Center, and its first major victory was an Appeals Court ruling upholding an Atlanta factory owner’s right to shut the doors on any OSHA inspector without a search warrant.

The Southeastern Legal Foundation also sought — unsuccessfully — to persuade the Supreme Court to allow construction of the Tellico Dam despite the snail darter’s protection under the Endangered Species Act. The Foundation is now challenging Virginia Commonwealth’s affirmative action policy designed to add new women faculty. The national office in Washington now concentrates on providing backup services, fundraising, research and expert witnesses for regional affiliates. The Center’s chairman is founder J. Simon Fluor’s son, J. Robert Fluor, now president of the Fluor Corporation. He joins another Center trustee, Joseph Coors of Coors beer, on the board of the ultraconservative Heritage Foundation, which Ben Blackburn chairs.

There are countless other nonprofit institutes, centers, foundations and committees that subvert the struggle for human rights, including labor rights, with deceitful studies, direct mail appeals (often guided by the master of rightwing direct mail lists, Richard Viguerie) and strident lobbying. In their most recent major victory, the organizations named in this report, plus other giants like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable, concentrated their full energies on defeating the 1979 Labor Law Reform Act. “They literally blew it out of the water,” confides one insider in Congress. ‘‘They had every small businessman, medium-sized company and corporate leader in the country flood us with letters. They came in person. They came in groups. They twisted arms till there were no arms left to twist. I’ve never seen lobbying like that in my 20 years on the Hill.”

On a local level, these groups provide the necessary network for union busters — both modern and old-fashioned — to share information, personnel and money. Our study revealed nearly all the consultants and employer-sponsored associations discussed here are violating provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act by failing to report that their time and money go to “persuade employees to exercise or not to exercise ... the right to organize and bargain collectively” and “to assist employers in presenting their point of view to employees in connection with organizational activities by labor organizations.” Furthermore, any employer who spends money for outside help to influence any employee’s union beliefs is supposed to file a form LM-10 with the Department of Labor. Failure to file carries a minimal fine, and the government has been lax in enforcing even this anemic provision.

If companies were forced to report, however, and if the myriad of nonprofit union-busting organizations were forced to state on their membership and appeal letters that contributors must file with the government, these regulations might discourage some employers from subsidizing the present framework of anti-union consultants. Making union-busting professionals and their supporters register, and thus become possible targets for union-sponsored lawsuits, would obviously influence the kind of support a Fund for Individual Rights or Capital Associated Industries receives. In recent months, congressional hearings on union busters, and increased enforcement by the Labor Department, have slightly improved the situation. But at this point, local organizers still confront hostile companies at an extreme disadvantage, often not even aware of the cast of consultants, lawyers and industrial psychologists that stand behind the company.

The fact that labor can face these odds and still occasionally win is testimony to the determination of workers in many locations to have the full rights of collective bargaining. The bristling array of company tactics also suggests why modern unions depend increasingly on their own lawyers and consultants. The UMW’s Brookside strike of 1973 and 1974 pioneered many techniques — including a sophisticated media campaign, consumer organizing and Wall Street pressure tactics — that have since been adopted by other unions. But organizing efforts are still shaped all too often by management’s force and strategy. The J.P. Stevens campaign, which has taken many turns in strategy over the last 17 years, has been most affected by the company’s willingness to fire, transfer or otherwise intimidate prounion workers. Before the union could establish its credibility as an organization that helps workers in the South, its lawyers first had to prove a more basic reality — that workers who express an interest in union affiliation will not be singled out and victimized with impunity by their employer. Hence the union and company have spent incredible energy fighting each other in courtrooms over the proper redress for Stevens’ obviously illegal behavior. Courts bound by the limits of the NLRB can still do very little to stop Stevens — or any other company — from firing, spying, buying off or harassing employees.

Until major reforms come to the NLRB, a union can win only through the dogged persistence of its entire organization and the self-conscious commitment of the local workers who want its benefits. Without reforms in the nation’s labor-management relations laws to ensure swift and substantial punishment of employers who repeatedly break the law, unions in America and the South face a difficult — nearly impossible — task every time they attempt to organize workers in a company advised by shrewd consultants. And even if the reforms pass — which is doubtful unless rank-and-file union members and unorganized workers join the sorely outgunned union lobbyists in pressuring Congress — even then, the only factor that will keep a union in a local plant will be a well-trained, active local which is ready to withstand the deadly plotting of management to co-opt, weaken and ultimately silence the collective voice of workers. In the evolving dynamics of American labor-management relations, labor must continue to pit committed people against the everchanging array of agents hired by big business. It took a massive movement of dedicated workers to pressure Congress to harness company gun thugs in the 1930s; today, only a united effort at the local and national levels can effectively challenge the power behind the corporate attorneys, crafty consultants and right-wing lobbyists.

In addition to their research and interviews, this report is based on work done over the last several years by interns and staff members of the Institute for Southern Studies, including Patty Di/ley, Margaret Lee, Bob Arnold, Jim Overton and Susan Angell. The authors would also like to thank Dick Wilson and Charles McDonald of the AFL-CIO’s National Organizing Coordinating Committee, which publishes the monthly RUB Sheet: Report on Union Busters.

George Hood: "I'm the Leg Man"

The following interview with union buster George Hood was conducted by Tony Dunbar in the summer of 1979. It provides an unusually candid picture of the perspective, problems and personality of a modern anti-union professional. It’s also an example of a skilled interviewer at work. Tony Dunbar’s questions are set in italic type.

I’m in a position right now of being able to write about things that particularly interest me, and one of these ... is to do sort of an examination, or re-examination, of “Southern individualism” as a movement and as a philosophy. ...lam going to publish it, but I’m not sure where or when. I had a good talk with the folks at the North Carolina Fund for Individual Rights, and they suggested you.

Well, let me just tell you something first. I was born in Columbus, Georgia, but my folks are New England Yankees, and I grew up there. We moved up when I was six, so I guess I’m kind of inclined to tell things like they are. I’m not very good at covering up anything.

The story of the SEE-Fund at this point is principally the story of the J.P. Stevens thing. We’re working with other people. In fact, I made two stops coming over. I would have stopped in Salisbury and seen some Fiber Industries people I’m working with, but they’re in good shape, and I can pass them by this time. But the Textile Workers Union . . . has been working on Stevens people for 16 years, since 1963. Right here in Shelby was one of the first places where they made any real attempt — at the Cleveland plant of Stevens. They arrived here, I think, in ’64, and I believe it was about ’67 or ’68 when they petitioned for an election here, and then apparently just prior to the date of the election the union asked that their petition be withdrawn. One man here, one hourly employee (a loom fixer) pretty well, near as I can tell, gets the responsibility or the credit for discouraging the union back at that time from proceeding with the election.

They disappeared for a while and came back again a few years ago. I don’t know just when. And this same fellow was still here, still on the same job, and is still battling with them. I’m here every other week trying to give this fellow some material and moral support. At least he isn’t having to pay whatever his expenses are today, as he used to have to, whether it was handouts, or ads, or T-shirts, or whatever. He’s done it himself, and now that’s the kind of job we’re taking on.

SEE-Fund exists, then, to give material and moral support to the employees who are trying to stay out of the union?

Right. Roughly two or two-and-ahalf years ago the union announced a boycott as a means of bringing Stevens to their knees. And at that time that was a terrible tactical mistake in my opinion because it hasn’t really accomplished very much for them. In the big cities apparently they get a little publicity, but the sales figures show that the business is continuing to grow more than inflation.

But why it was really a mistake was that up to that point many of the employees had been kind of lethargic. People at Roanoke Rapids had a union and some negotiating going on, but the employees were unhappy, really. Then the boycott came along. This was a threat to the employees’ jobs; that’s the way they interpreted it, and this was what the union hadn’t perceived. And the union continues to ignore this fact. But all of a sudden this just brought many of them out in the forefront, and they formed an Employee Committee in Roanoke Rapids. They formed one in the Greenville area — several plants there; Bill Blanton was already working here in Shelby, and a group formed in the Stuart, Virginia, area where there are four Stevens plants.

And in each case there were business people and others in the community who were interested in helping them, mostly in a small way. But some of them provided a little money. T-shirts would show up being delivered by UPS, and nobody knew where they came from. Bumper stickers, badges and that sort of stuff.

Most all of them have stayed anonymous, except one fantastic guy in Martinsville, Virginia, who’s not a Southerner, Julius Hermanes, who owns Martin Processing Company, has claimed, and there’s no question in my mind about it, to have spent more than $10,000 supporting Stevens people up there.

We also think that he’s been responsible for some of the bumper stickers, badges and things that have showed up in other places. And I’ve got probably 75 or 100 T-shirts in my car right now that came from him that I picked up in Roanoke Rapids last night and will take to Wagram, North Carolina, when I get back from Greenville and Anderson, South Carolina, Thursday.

The group and their advisors in Roanoke Rapids, and the group and their advisors in Greenville both about the same time got to thinking, “Gee, we ought to formalize this thing and provide a vehicle which people could make tax-free donations to.” So that’s where the SEE-Fund started, and it didn’t become at all concrete until last August at which time one of the attorneys, Bob Valois in Raleigh, who had been working with the thing, said to some folks, “Why don’t you see Joe Beard in Charlotte. He’s involved in

“I’ve got probably 75 T-shirts in my car right now that came from him that I picked up in Roanoke Rapids and will take to Wagram.”

raising money for some good causes, and he’s not the busiest lawyer in the world. He can put together your corporation and get your IRS status and so forth.” So that’s what happened.

How was Bob Valois involved?

Valois was hired when the Roanoke Rapids people got upset about the boycott and said, “Those bastards are going to take our jobs.” They went to several lawyers in Roanoke Rapids and said, “We’ve accumulated about $530 among ourselves, and we want to hire a lawyer to help us get this damn union out of here.” They all said, “Well, we work with J.P. Stevens one way or another, but we’d recommend Maupin, Taylor, Ellis, Valois in Raleigh. They specialize in labor law.” So they went over and saw Bob Valois and laid their $530 and some-odd 44 dollars on the table and said, “Will that get rid of the union?” He said, “Hell no, nowhere near,” but he was impressed of course with their determination, and he is one of those rare, if you’ll pardon my bias, lawyers who’s motivated by something other than just money.

That does make him a rare lawyer.