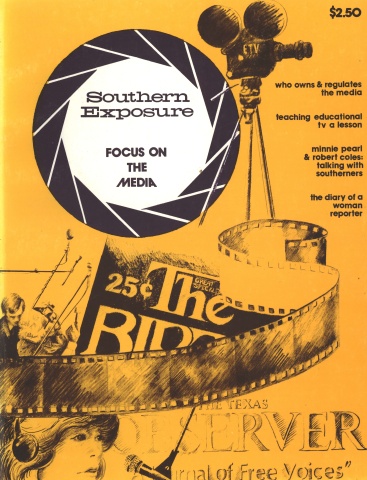

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

During the late '60's and early '70's, a small press boom hit the country and the South. Scores of papers sprang up, flourished briefly, and died. One of them, the Kudzu, was published by myself and others in Jackson, Mississippi, from 1968 to 1972. In those days, Tom Forcade of the Underground Press Syndicate liked to startle people by pointing out that the South had more underground papers in proportion to its population than the rest of the nation. But it was no surprise to us. After all, writing and music have long been the prominent modes of expression in the South, if for no other reason than the economic reality that printing is the cheapest medium, and therefore the most accessible one to Southerners.

Economics has a lot to do with the media, as does the larger political and social situation surrounding the people who use it. As a Southerner, I am also keenly aware of the intimate relationship between past and present. So in telling the story of the Kudzu, a little background is appropriate, and a continual reference to the broader political picture is necessary. And since the Kudzu, like many papers of the period, was largely a one-man show —despite all our efforts to the contrary— this story is also a personal account of my own experiences.

I.

The black community in Mississippi had begun moving into action in the early '60's, with the Freedom Summer of 1964 highlighting the times; at the time, only sporadic connections existed between local whites and the Movement. The first competent attempts to reach out to local whites in Mississippi were made by the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC) beginning in 1966. (Of course, I am speaking here of radical organizing, the term radical meaning loosely an approach to social change which seeks to go beyond mere reform, which seeks to build a consciousness of the inevitable need to change, from the roots up, all of the basic social, political, and economic institutions of society.)

When SSOC began organizing in Mississippi in 1966, I was a sophomore at Millsaps College, a small Methodist liberal arts college in Jackson. Millsaps was a place where kids went who didn't. have the grades or money to go to a big name school out of state; also a good number of working-class kids on scholarships and loans went there. I grew up the son of a rural Methodist preacher in north Mississippi, and as is usual with young Southerners with intellectual pretensions, my biggest ambition was to get away from provincial Mississippi to experience the supposedly exciting life in the urban intellectual centers. That being beyond my means or know-how in 1966, the next best thing was to make contact with the young intellectuals from New York and San Francisco who came to Mississippi to work with the Civil Rights Movement. I also became involved as one of the earliest and most consistent Deep South contacts for SSOC, a relationship which lasted for three years, and I began reading the Movement papers such as the National Guardian and the publications of SSOC and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

I wanted very much to expose other young Southerners to the information I was coming into contact with for the first time. Jackson's two newspapers, the biggest in the state, were so notoriously right wing that even Ho Chi Minh, on the other side of the world, had singled them out for special comment. (I forget the exact quote, but it had something to do with using racism to divide the working class.) I felt that much could be gained by just communicating progressive information and analysis to people. But I was faced with the traditional southern reluctance to take “outside propaganda" seriously. A possible solution to this obstacle seemed to be to produce a purely local publication which presented information in language more tolerable to local whites than the often excessively rhetorical language of the Movement press.

My earliest compatriot in this endeavor was Lee Makamson, an ardent political science major and debater from a working-class family in Jackson. Lee used to say that if he had been alive back in the early historic days of the labor struggle, he would have wanted to be involved in that; and since civil rights was the historic struggle of his generation, he jumped in with both feet. In late 1965, Lee and I began publishing a mimeographed sort of newsletter called the Free Southern Student, which we passed out to friends at Millsaps and mailed out to a few other students we knew in the black and white schools around the state. We used the mimeograph of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The Free Southern Student contained our opinions on civil rights and the Vietnam War, and a smattering of factual reporting on various civil rights projects we visited around the state. It was not, however, a mass publication and its effects were indeterminant; I think we printed four or five issues altogether.

In the spring and summer of 1966, I began traveling to southeastern and national civil rights and antiwar conferences. I joined the James Meredith March from Memphis to Jackson and finished out the summer working for the Freedom Information Service, a small staff organization in Jackson which serviced the Mississippi Movement with research and information. I returned to Millsaps in the fall more determined than ever to communicate with other students. Lee, however, had unexpectedly become disillusioned with publishing. Alone, I printed one issue of a sequel to the Free Southern Student which I called the Mockingbird, a play on the state bird and my intentions of mocking the status quo. My plea for help with the publication didn't get a single positive response, so I abandoned the project.

During this period, a new dynamic arose —the hippie movement. While the Movement had been my only means of escape from the straightjacket of Mississippi, younger students had found another avenue to freedom. Consequently, those few young people in Jackson who might have joined me in throwing in with the Movement grew long hair and played rock music instead. Not that they felt no kinship with the Movement, but integration was moving along without their help, was actually moving faster than anyone had expected, and the Movement leaned more and more toward a theoretical and rhetorical approach which intimidated all but the most intellectually oriented young people. Besides, the new hippie movement was far more glamorous. So over the next two years, drugs and music took precedence over political activism among those few white young people inclined toward rebellion against the ways of previous generations in Mississippi.

One incident alone during this period brought the emotional appeal of the civil rights struggle temporarily back to the forefront. In the spring of 1967, a sequence of loosely organized events surrounding student protest about traffic passing through the center of the predominantly black Jackson State College campus culminated in the shooting of a local civil rights worker by the police. A number of facts tended to discredit the official story that the man was part of a street crowd attacking the police, including the fact that the man, Benjamin Brown, was shot in the back. It appeared that at best he was the victim of typical police overreaction and at worst he had simply been recognized and murdered by a cop.

The following morning several of us at Millsaps made up some quick placards and organized a march to city hall. We were prepared to march with as few as five students, but were amazed to find twenty people lining up to march. Now this may not seem like very many people, but only two of us had ever been in a political demonstration before. And this was Mississippi. Everyone on the march was calling forth completely unknown consequences at the hands of school, family, friends, future employers, and the Ku Klux Klan —not to mention the police, who had the night before gunned a man down in public. It was the first demonstration of this type in memory, maybe ever, carried out solely by Mississippi whites, and it was a little different from your usual Movement march. The president of the junior class, who was also a first string lineman on the football team, took my placard away from me and led the march; and the campus karate champ strolled along beside the line to protect us from any threatening bystanders we might encounter. Well, nobody got shot, or even kicked out of school, but the event made the NBC evening news and caused untold turmoil in twenty Mississippi families immediately thereafter. It also threw a godawful kink in the school's big drive to raise funds from conservative alumni to match some promised Ford Foundation money.

That march was one of the most powerful experiences of my life. It was one thing to work and demonstrate with northern students and blacks; it was many times more moving to do so with my own people. In retrospect, however, problems appeared at that point which haven't substantially changed even now. The march indicated the potential strength of average people — and the Movement's failure to reach them on a day-to-day basis; thus, after the Ben Brown controversy, things settled back into the previous apolitical stupor.

II.

By the spring of 1968, the continuing impact of the national student movement had created an atmosphere which left some of the more morally inclined students—whether hippie or not —feeling a little restless to get on with things like ending the Vietnam War and reforming the university. A controversy developed at Millsaps over the firing of an anthropology instructor who had come from Columbia University two years before. The alumni had gotten upset about his research into social change in Mississippi, and the administration was uptight about his fraternization with the most rebellious elements of the student body, namely myself and several others. In response to this issue and to things in general, a number of us began publishing a little mimeographed publication of satire and comment called the Unicorn. I'll never forget the experience of walking into the school cafeteria right after the first issue had been passed out and seeing a couple hundred people intently pouring over our writing; after the previous years of frustration, the sense of communication was so gratifying. I was hooked on writing.

The trick that made it all so different from the old Free Southern Student and Mockingbird, the trick it took the hippies to teach us, was to make the publication more general in appeal and content. We used the Freedom Information Service's electronic stencil maker which copied illustrations, got artists to draw covers and cartoons for us, and published poetry and music commentary and other things besides dry, serious political writings. We had the writers from the censored school paper doing stuff for us and the whole thing was a great success. We probably could have made money if we had sold Unicorn, instead of giving it away. That spring we had an antiwar demonstration which we promoted as a "Peace Parade" with cars decorated with banners and crepe paper. The most successful organizational approach, both in terms of getting the participation of young people and communicating with the rest of the population, seemed to be to combine the aesthetic concern and fun-loving nature of the hippie movement with the political insight and moral direction of the civil rights and antiwar movements.

Another major event occurred in the spring of 1968 —the beginning of Atlanta's Great Speckled Bird. Many of the Bird's founding staff members were friends of mine through SSOC. I watched the Bird take shape and decided that such a paper could be done in Mississippi on a smaller scale and would be the most effective tool for organizing and communicating; besides, I really was hooked on writing. That summer I went to Atlanta and lived in a basement room of the Bird office on 14th Street for about a month while I learned the necessary technology and skills. Photo-offset made it all so simple and cheap; you just type your stuff up, paste it down with the artwork, mark spaces for the photos and give the whole thing to a printer, who photographs your pasteup and makes plates from his photocopies. Several thousand copies of a tabloid size could be printed at a cost somewhere around 10 cents a copy.

Also, during that summer I became the Mississippi organizer for the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC). Few people knew anything about SSOC; its history was brief, its development rapid, and staff turnovers so frequent that even people who were at one time or another part of the staff have an incomplete comprehension of SSOC's development and demise. In certain fringe areas of the South such as Texas and Florida, SDS was the major white student organization, but in most of the South SSOC played the major role. Its influence was so strong on us in Mississippi, and on other individuals and small groups working in isolated places in the South, that in some ways a discussion of SSOC is the beginning point, and in too many ways also the end point, of the story of my generation's experience of radicalism in the South. In many ways what happened to the Kudzu and other small press operations in the South was merely a delayed echo of what happened to SSOC.

SSOC was organized in 1964 by several young white Southerners who had been active in SNCC. At that early date they perceived what the national Movement learned somewhat later, namely that although integration was a beautiful ideal, it simply was not a practical reality at that time. Meaningful organizing required that blacks organize blacks, and whites, who were the real problem anyway, be reached by whites, and in particular, southern whites be reached by other southern whites.

In addition to their experience in SNCC, most of the original founders of SSOC also had roots in the few progressive, somewhat covert activities of southern churches, although by this time little vestiges of religiosity remained. From its headquarters in a small house in Nashville the staff raised funds, organized conferences, coordinated regionwide demonstrations, published a regular magazine and many pamphlets on various subjects, and sent out campus travelers around the South. Essentially, it operated as a loosely-knit network of organizers trying to keep up with the developments in the national Movement and at the same time reach out to the most unsophisticated, provincial, and reactionary constituency in the country.

After joining the SSOC staff, I began using Mississippi's share of SSOC's budget to publish the Kudzu, although most of the money came from local supporters and subscribers. At that time, it would have been impossible to say which meant more to me, SSOC or my dedication to the Kudzu and to changing Mississippi. When we started in the fall of '68, I was the only full-time member of the Kudzu staff; everyone else went to Millsaps, but by the spring a few others had dropped out and the full-time staff fluctuated around four to six members.

We were never doctrinaire leftists but instead were enthusiastic supporters of the new youth movement. Marxist-Leninism looked just great when you sat home and read about it —and we all began our understanding of economics with Marx — but I came to believe that while Marx was a genius at analysis, the father of social science, he was lousy at predictions. Revolution had not occurred in the industrialized capitalist nations as the old left claimed was inevitable. Revolution had occurred in the least industrialized countries and long years of practicing doctrinaire Marxist-Leninism in the U.S. had resulted in virtually nothing and only slightly more had been accomplished by Marxist-Leninists in Europe. It seemed clear that something more was needed and the new youth movement was the best we could do for the time being. It made no more sense to me to go out and try to coerce the American people into swallowing the CP line than it would have for me to try to get people to join my father's church; on the other hand my own generation was onto something which was spreading like wild fire and which seemed to offer unlimited possibilities for revolutionary change.

III.

Organizationally, the Kudzu was small enough that a maximum of democracy could be practiced. We decided on the content of each issue by consensus and nobody did much specialization. We more or less did things all together as the need arose. People would write for a few days, then we'd type up copy and start pasting up. When the paper was printed we'd all spend the next few days mailing out the subscriptions and exchanges and hawking the paper on the street.

We were scrupulously legal, but arrests were inevitable. We dared not print anything that could be construed by a judge as pornographic, and our political writings were quite mild by national standards, certainly nothing that could easily be called seditious. We showed no nudity to speak of but we often wrote in a conversational style interspersed with everyday slang. We wanted to bring the printed word down off of its bourgeois intellectual pedestal, and we felt it was class prejudice that prohibited the public use of the old peasant Anglo-Saxon four letter words. We wouldn't really have been disappointed if there had been no arrests, but we were ready for them. Several lawyers in Jackson had extensive experience dealing with the local authorities on civil rights cases, and we had great confidence in them. A rash of arrests of Kudzu vendors around high schools broke out with our second issue. Everyone on the staff was busted at least once. The charges ranged from assault to vagrancy, all false and all eventually dropped. But the publicity turned out to be just what the paper needed to get off the ground. The second round of arrests were for “pandering to minors," four letter words being the issue; these cases died two or three years later in federal court.

An accurate account of arrests, atrocities, and major incidents of harassment would be a whole story in itself; we averaged several arrests a month throughout the first year of publication. Most arrests didn't involve any brutality, but beatings occurred often enough that one could never be sure what to expect. The Kudzu also catalyzed a number of other incidents such as high schoolers getting sent off to military academies and college students being cut off from financial support from home. Things were moving very fast and we felt we were breaking a lot of ground and reaching huge numbers of people, so we really didn't care how often we got thrown in jail as long as we kept getting back out and kept publishing. The arrests drained time and energy from us, and sometimes it looked like we wouldn't be able to come up with bond money; but somehow we always found a handful of liberals willing to risk putting up their suburban homes as property bonds, and fortunately we never sustained a conviction except for a few traffic violations.

We considered ourselves very fortunate in that we never came under any serious physical attack from the right, except from the police themselves of course. We got threatening phone calls all day and night, and one time somebody loosened the lug nuts on our VW's front wheels hoping we'd wreck before we discovered it. Then there was one guy who took to following us around, but we eventually confronted him and he started coming in the office and arguing politics with us. And just once somebody fired a .22 through the front window several times. But considering where we were, and considering things that happened to others, Mississippi's renowned night riders never really did anything to us to speak of. Just the same, nobody ever did anything so rash as to spend the night in the front room of any office or house we ever had.

We worked hard that first year. We were called lazy hippies and the police charged us with things like loitering and vagrancy, but we worked sixteen hours a day. We didn't try to get a printer in Jackson; even if we could have found one, it would have been too easy for pressure to be brought to bear on him. We had a printer in New Orleans, a black man and a Kennedy liberal who printed the Louisiana Weekly. He had a lot of sympathy for what we were doing and gave us good rates and most important of all, credit. We would stay up all night finishing the layout and then take off at five o'clock in the morning for New Orleans trying to make the printer's nine o'clock deadline. While we waited for the paper to be run off, we usually visited the staff of one of New Orleans' underground papers, most notably Bob Head and Darlene Fife's NOLA Express. New Orleans became our second home, and one or another of us made the four hundred mile round trip to New Orleans once or twice a month for the next four years. We had a hundred thousand breakdowns and the car left the road with us twice that I was a witness to; I guess as long as I live I'll have nightmares of breakdowns and crackups between Jackson and New Orleans.

Our first issue was laid out on the kitchen table of an off campus apartment near Millsaps, and as a writer for Rolling Stone later wrote, the Kudzu always looked like it was actually printed on the run. The truth of the matter is that over the next four years we operated out of an oft changing succession of rundown rental properties. Only once during our third year of publication did we operate out of an actual office in a business district. That brief period ended one night when somebody snuck in the back window and set fire to the place. One of us just happened to come along at three a.m. and call the fire department before much damage occurred. At that point, we had a falling out with the landlord and went back to our usual arrangement of operating from a post office box and the kitchen table.

It was a rough existence in those early days. Five to fifteen people and a newspaper office crammed into some rundown one or two bedroom duplex. You had to eat, sleep, and work all day and night, every day and night within the same four walls and with the same people — except for the ever-present and ever-changing assortment of high school runaways, political travelers, California hitch hikers, etc. And while these people were a constant stimulation (and also distraction) in their own right, there inevitably followed in their wake knocks on the door by juvenile officers, parents, and FBI agents. We found ourselves learning many new skills, like how not to get attached to small articles which might disappear in the morning with last night's hitchhiker, and how to get a night's sleep undisturbed by ringing phones and knocks on doors, and how to tactfully ask someone we just met to shut-up and please leave the room while we held a staff meeting.

Naturally, under such conditions there were constant personality problems and in fact the ability to work out one's personal problems (either collectively or individually) quickly became an automatic prerequisite for survival on our staff. Of course, collective solutions were what we knew should be happening, and things ran much smoother when we forced ourselves to take the time to sit down periodically and talk things out rather than waiting until things built up beyond the point of no return. The struggle between individual freedom and collective needs within our little group was in our minds as much as the greater struggle of the Movement. Invariably it became clear how a person's politics and personality were inseparably related: those who tended toward anarchism were sometimes undisciplined and irresponsible on a personal level, and authoritarians sometimes disregarded democratic and egalitarian ethics in personal struggles. We found that while we struggled toward a certain idealized concept of interpersonal freedom and egalitarianism, it became necessary at times to draw the line and exclude disruptive individuals.

For me, the living and working conditions were the worst, and the pressures, publicity, and the harassment were the most stressful that I ever experienced — but it was the happiest period of my life, before or since. The best integration I could ever hope for of my personal talents, skills, background and interests with my moral goals occurred during these years. We felt we were accomplishing so much and threw ourselves so completely into dealing on a day-to-day basis with the greater moral issues of life. We really felt that we were an important part of humanity's struggle through history. It was the most fulfilling, meaningful, productive, and creative period of my life.

But I had never known how long to expect the paper to sustain itself. I had gone into the first issue fully prepared that it be the last, believing that even one issue would be better than none; if we came out of it able to publish a second issue then so be it, and on and on, issue after issue, for as long as it lasted. But the initial rapidity and intensity of our success only served to make more depressing the lack of direction and activity of the subsequent years. Really, I'm not over it yet.

IV.

In the spring of 1969, SSOC was reluctantly dragged into the national Movement's accelerating whirlpool of self-indulgent factionalism, hair-splitting rhetorical debate, and violence fetishism. Before it was all over the SSOC leadership had lost the support of any real constituency in the South, and SSOC was ostracized and denounced by SDS on the basis of highly questionable factionalist grounds. At that point SSOC dissolved itself. SDS's own dissolution was just around the corner.

But even before it became clear that SSOC and SDS were finished, I resigned from SSOC because I could see that even if the organization continued, it was irrevocably committed to a preoccupation with debate and theory. It was going nowhere that would help me in the everyday struggle in Mississippi, and that struggle in the end was the, only hold on anything real that I had. I really could find little help from the rhetoricians and debaters in SSOC and the national Movement. If it didn't help me deal with the people I had grown up with and lived among in Mississippi, the only people in all of history and in the whole round world that I really knew —the guys who I started to school with in the first grade and who came to school in overalls and bare feet and who grew up and worked at the corner service station, and the girls who wore dresses made out of flour sacks and who grew up and worked at the garment factory or in the dime store — if it didn't give me something to say to those people then I didn't want anything to do with it. If you couldn't talk to those people in their own language and say things to them that they could immediately relate to themselves, then you had nothing to say to them at all; all the meetings and conferences and debates and pamphlets and books were worthless unless they could help us develop something to say to those people, and the Movement was suddenly doing everything in the world but that one supremely essential thing.

But if SDS and SSOC were a lost cause, they weren't the whole Movement. The underground press was a mushrooming phenomenon all over the country, and papers seemed to be drawing in people who were more oriented to real communication than the organization freaks of SDS and SSOC; and these people also tried to integrate the divergent tendencies of pure politics and apolitical counter-culture, an integration that seemed essential to real communication. Even in the most backwards areas of Mississippi, young people of all classes were attracted to the hip culture by the mass media, and they were simply too turned on by the newness and excitement of it all to be susceptible to a purely political approach. They literally demanded greater and greater exposure to the new culture with all of its wide-ranging concerns. But as their participation in this new culture increased, they came up against the same brutish, reactionary, intolerant Mississippi power structure that the black activists had been fighting all those years.

We forgot about SDS and SSOC; the battle was right here in our own back yard now. We had to stake out some kind of sane territory which somehow balanced the superficial and naive idealism of the hippie love and anarchy tendencies with the deeper and more realistic understanding of society that politics could provide. This was the goal of much of the underground press at that time, and we exchanged publications with hundreds of papers all over the country and the world and went to occasional regional and national conferences of the Underground Press Syndicate. In Mississippi, we were building up a growing network of contacts around the state, mostly on college campuses and to a lesser extent in the high schools.

In the spring of 1969, we organized “The First Annual Mississippi Youth Jubilee." We used a former college campus leased to the Delta Ministry, a left-liberal civil-rights-oriented project of the National Council of Churches, and showed a bunch of Movement films and had a few speakers and discussion groups and invited local rock bands to come play Saturday night. The Jubilee was all things to all people. For some people it was just a party, but there was substantial participation by most of the two or three hundred people in the politically-oriented functions.

Saturday afternoon the highway patrol illegally entered the grounds and provided a fruitful center of focus. They had lurked around the entrance the whole weekend checking licenses, issuing an occasional ticket. Saturday they took to cruising through the campus without permission or invitation, and on one of their incursions an irate crowd closed in around two of their cars and prevented them from leaving. We confronted them and told them they could either buy a ticket like everyone else or they could promise not to return. When they refused to do either, people started breaking bottles in the road where they would have to pass. A heated debate started between the pacifists and the bottle breakers, and the pacifists picked up the broken glass and the patrolmen left. During the rest of the weekend, we kept the entrance blocked with cars so they couldn't return. The incident greatly enhanced everyone's sense of solidarity and collective power and it stimulated a lot of creative interchange over the issue of how to deal with repression. A statewide organization was established to keep people in touch and to plan another Jubilee the following year.

V.

The next years were a downhill struggle. We printed twice as many issues of the Kudzu during our first year of publication than in any of the next three. We became a monthly publication and finally couldn't even make that. We were never able to develop an advertising base and had to depend solely on the income from sales. But distribution was so bad we never really scratched the surface of our potential readership. Newsstands and commercial distributors refused to touch us, so we had to depend on student volunteers and a sort of hand-to-hand distribution system. Sometimes we had good distributors on the campuses and sometimes we didn't; and sometimes they sent us the income from the sales and sometimes they didn't. We didn't have the time or the means of transportation to make the rounds of the campuses and small town distributors. And Jackson is not a very big city and street sales were never profitable enough for us to develop reliable street hawkers. We usually ended up standing on the street corners ourselves, more to see the paper reach people than to make even enough bread to feed ourselves and pay the printer. A small core of left-liberals composed of the Delta Ministry people, a few holdovers from the earlier civil rights movement, and a few older local people kept a trickle in our bank account that helped us subsist. But we found it necessary to take turns holding down outside jobs and sharing the income with the rest of the staff. That worked for awhile, but as the years dragged on and self-sufficiency became more of a dream than a real probability, the personal strain of that arrangement became too great and the sacrifice became less and less justifiable.

But living in Mississippi had always been a constant struggle financially; hell, half the population of the state, white and black both, walked around scarcely knowing where their next meal was coming from, and always had. Back in my civil rights days I had walked the streets of Jackson collecting pop bottles from the gutters to get grocery money, had rolled countless cigarettes from stray butts found in ash trays, and learned to make the best of every opportunity to eat leftovers off the tables in restaurants and lunchcounters. No, it wasn't the hard times that finally got to us; God knows we knew how to live with that in Mississippi.

What took' the wind out of our sails was looking on the disarray of the rest of the nation and finding nothing real out there to identify with. Within a year of SSOC's demise SDS itself splintered into several factions and lost its national following. I was too busy with the Kudzu and things in Mississippi to even say "I told you so." But over the next three years the loss of national organization made itself felt more and more and before it was all over I came to realize that as important as local roots were, they could be rendered worthless by the isolation that the lack of national solidarity imposed on us. Liberation News Service had split down the middle over the counter-culture versus purist politics debate. The cultural faction disappeared into Vermont or somewhere and all that was left was the verbal diarrhea of the New York political heavies. Other underground papers around the country seemed to be moving relentlessly down the trail SDS had blazed of being increasingly obsessed with purist politics and violence fetishism. Meanwhile the whole counter-culture thing became increasingly superficial and reactionary under the onslaught of commercialism and escapism; and if that wasn't enough, people were taking more and more of a depressing turn to the mindless mysticism of religious cults and astrology. The middle ground of sanity disappeared and with it our hopes for the emergence of an effective national Movement. One after another Kudzu staff members became frustrated with the isolation of Mississippi and packed up and headed out for parts unknown.

But for awhile new people kept joining the staff, and if we no longer had quite the energy and vision of our original mission, we were at least turning out bigger and bigger demonstrations against the Vietnam War and recording Mississippi's recurring brutalities. We were there when the highway patrol, led by the same man we confronted at the Jubilee, shot up a crowd of black students at Jackson State College wounding a dozen and killing two; and we were there to cover the way the Jackson police provoked the Republic of New Africa leadership into a shootout and railroaded them into prison. One of our staff members, a former small town high school football first string guard, went to Cuba with a Venceremos brigade and managed to cut enough sugar cane to get elected a brigade leader. We had one more Jubilee, but our staff was too small by the third year to organize another one. The statewide organization formed at the first Jubilee withered from lack of national involvement.

During our last two years of publication, we recognized that the Kudzu would not achieve self-sufficiency in the foreseeable future, so we began working on a biracial youth community center hoping that it would have a better chance of survival and that we could support ourselves and keep the Kudzu going on the side. There was constant harassment from the police and from a right wing motorcycle gang. At one point it got down to me holding off with a 12-gauge shotgun a group of the bikers who were trying to rob the cash box. They weren't happy with the stand-off, and immediately went over to the Kudzu house, beat up the only person there, and stole a bunch of stuff. I moved out of the house and slept beside a gun for a month after the incident — they had sworn to see me dead.

After about a year and a half with the community center, we found ourselves unable to raise the funds to mount the necessary court battle against legal technicalities the City Hall threw up against us and we had to close down the center. The closing of the youth center was sort of the last straw. At that point, only two of us were keeping the Kudzu going, and the other person besides myself was driving a taxi twelve hours a day to keep us going. We were beating a dead horse. In the spring of 1972, we packed up the paper's files and gave them to Delta Ministry and I left Mississippi.

I had corresponded with Liberation News Service about writing for them. They had no one on their staff from the South. But finally they said they were trying to maintain a ratio of two-thirds women to one-third men on their staffs and couldn't take on any more men at that point. I went to Atlanta to see about working on the Great Speckled Bird. Several of the people wanted me to stay there, but when I criticized the Bird for losing its once large readership because it wasn't reaching people, some East Coast intellectual who had recently joined the staff called me a "tailist" for wanting to lower myself to where the people were at. It was the old chauvinism. I was just a bumpkin from the provinces who hadn't read enough Marx and Lenin. These people were just as happy as they could be sitting there being irrelevant and unread; I made plans to leave.

I wanted to take out a full page ad in every Movement paper in the country and say, "Well, what about 'failurism!' Doesn't anybody on the left care that the left's most consistent characteristic in this country is its failure to initiate and sustain real communication with the American working people?!" My experience was that nobody really did care. People cared about establishing their place in history as a Movement leader; they cared about working off their guilt for being middle or upper class by passionately embracing intellectually whatever the Movement's latest trend was; they cared about advancing their intellectual prestige in debates, and any number of the other games the intellectual class occupies itself with. But the American left has rarely been able to see the peculiarities of its own subculture and to transcend those peculiarities to establish communications with another culture, the culture of working-class America.

I got a job doing construction; not for any political reasons, but just to make a living. After two years of construction work, I've gone back to school to try to find something worthwhile to do with myself in the area of health care. Maybe I can find a way to express how I feel about people in a personal way even if I can no longer do it through the Movement.