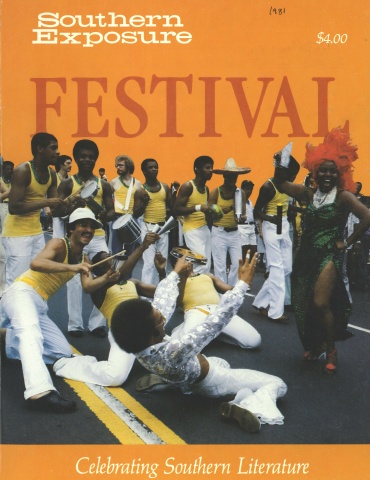

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 2, "Festival: Celebrating Southern Literature." Find more from that issue here.

Since childhood I have been fascinated and influenced by storytelling. I can remember as a boy listening for hours as my grandmother told me stories: tales about the wildcat that fell down her mother’s chimney into a vat of water and she boiled it down to “rags and molasses;” and about Captain Rudd putting out a big hotel fire, then sitting down to eat breakfast in his undershirt at a table with six high society ladies; and about the time she was riding the trolley and looked out the window, mortified to see her husband and her son pulling a circus wagon they’d won in a poker game.

It was not long before I was imitating my grandmother’s storytelling techniques and strategies. I was soon the neighborhood storyteller. As dark came on, kids gathered round me on my steep porch steps to hear my versions of movie or radio heroes. When rain or snow kept us indoors at recess, I leaned against the blackboard and told the class more tales about Huck and Jim. As we sat on the tracks, waiting to hop a freight to a swimming hole out in the country, I told the adventures of a kid who was a fantasy projection of myself. In a dormitory cell in the juvenile home where my brother and I lived while my mother was hospitalized, I told ghost stories, while kids huddled under my quilts and under my cot, risking a whipping.

Before I ever read any fiction, I had already written 2,000 pages of stories, radio plays, movie scenarios and poems. Bijou, an autobiographical novel, depicts the transitional year, 1946, in Knoxville, Tennessee, when I was a 13-year-old movie usher, telling stories while writing them, enthralled by the movies, and only just beginning to read. A year later, I had read Wolfe, Hemingway and Joyce; their literary techniques overwhelmed the effects of the oral storytelling compulsion.

As I worked for 15 years on novel and play versions of Cassandra Singing, I was not very conscious of the enduring effect upon my writing of the techniques of the oral tradition, not even as Cassie, an invalid girl who lives in her imagination, and Lone, her brother, who pursues a life of action on a motorcycle, tell each other stories.

Writing “The Singer” (unrelated to Cassandra), in which movie and oral storytelling images compete and conflict, I became acutely conscious of my debt to the oral tradition and celebrated it in my dramatic readings. While giving about 300 readings of my fiction, North and South, over the past 13 years, I became increasingly aware of the almost mystical relationship between storyteller and listeners, and the profound effect that a well-told story has upon listeners’ imaginations.

In a novel of the same name, I describe the “Pleasure- Dome” — “a luminous limbo between everyday experience and a work of art.” The listener enters the Pleasure-Dome, as Lucius — the central character of Bijou — sometimes did while listening to his grandmother, only on those rare occasions when storyteller and listener interact most powerfully. It is the essence of that experience that I try to preserve in my fiction.

My fascination with the dynamics of storytelling clearly manifests itself in my work, where I have not only dramatized storytellers and their art, but in writing about them have worked out literary equivalents of oral technique. In my novel Bijou, there are a great variety of oral storytelling relationships, in various contexts, with other media inter acting: movies, radio drama, plays, popular and literary fiction and poetry, songs, games. Folklore and popular culture, like two decks of cards, are shuffled together, enhancing and conflicting with each other.

In this scene, Lucius’ grandmother Mammy’s storytelling is prompted by the family’s perusal of a large collection of movie stills a girl has just bestowed on Lucius. The family retells the stories of movies and alludes to episodes in their own lives.

Sitting in her favorite chair across from the front door, looking like Wallace Beery, Mammy reminded Lucius of the summer nights during the war when they sat in the open doorway in the blackouts and scanned the sky for German planes, telling stories by the bomber’s moon.

“Mammy, tell ’bout the time Gran’paw Charlie beat up the principal.”

“He didn’t beat him up, honey.”

“Tell it, tell it,” said Bucky, sitting on the magic carpet in front of Mammy.

“Well, children, the way it was, the principal sent little Luke home one day with this note to Gran’paw Charlie, sayin’, ‘Mr. Foster, it has'been brought to my attention that your son has poured library paste all over Mrs. Rankin’s erasers. I must insist that you accompany your child to school in the morning. Bring a switch with you, as I want you to be present when I give Luke a whipping.’” Mammy bent her head and rubbed her nose to recall the scene. “Boys, I tell you, when Gran’paw Charlie read that note, he hit the ceding.” Bucky looked up at the ceiling, Lucius looked up. “He stormed and he raged from room to room of this little of house, yelling, ‘that g.d.—’”

“He may a been just a little feller,” said Momma, “no taller’n you, Lucius, but he had a bullhorn voice. Used to go out and stand in the backyard and holler for Luke to come on in for supper and Luke, curb-hopping at Howell’s Drug Store, would hear him all the way through the woods, across Crazy Creek to Grand Boulevard and Luke’d come running lickety-split.”

“Irene, I’m telling this.”

“Well, pardon me for living.”

“So, next morning, Charlie says to Luke, ‘Son, go cut me two switches!’ ‘Two?’ ‘Don’t wrangle with me. I said “Two,” now git ’em.’ So little oT Luke drags hisself over to the hedge outsyonder and breaks off two switches - I was watching from the kitchen winder, wondering what Char lie was up to myself — when all of a sudden, Luke threw them switches down, and broke off a littler one and a bigger one, and come back in the house just a-smiling to beat the band. Looked like he’d figured something out, but I didn’t know what it was till Luke come home that after noon and told me.” Knowing what was coming increased Lucius’ fascination.

“Way it turned out, was this. Gran’paw Charlie marched hisself up to Clinch View Elementary, little Luke trottin’ behind — and he was almost by then as tall as his daddy — but Charlie was just like a buzz saw when he got wound up. So he sashays into the principal’s office, and this old man looks across his desk at this sawed-off little feller. ‘Wait outside, sir, until I’m ready to see you,’ says the principal.

“Well, he ort’n a done that. Should a kept his mouth shut and let Charlie talk. Charlie raises up on his toes — wore a size six shoe that’s even too small for you now, Lucius — and in that deep, cocky voice of his, says, ‘Mr. Turner, you will see me now, for I have come just like your note says, and I have brung two switches.’ ‘Two switches?’ asked Mr. Turner .. . and a hatefuller man you never met. Wore out a switch on Earl the second year he went. Dead now, ain’t he, Irene?”

“I don’t know nothin’.”

“So, anyway, Charlie says, ‘Yes, sir. One for you to use on my boy, and when you g’done, I’m a-gonna use t’other on you!”

“Then did he whup him, Mammy?” asked Bucky.

“Don’t know, honey. That’s the end of the story.”

Later that same night, as their parents fight, Lucius distracts his little brother, Bucky, with a story he is writing.

In the back room that Gran’paw Charlie built on when he and Mammy moved in, in Luke’s bed, Bucky, sticking his feet straight up under the sheet, asked, “Tell me a story, Lucius?”

The room’s only window was open, the honey suckle-laden air came through the latched screen door.

“Once upon a time . . . there was a mouse! And his name — was — Mighty Mouse!” Lucius announced dramatically, and paused, as Bucky, thrilled, kicked his feet rapidly, his body shuddering with delight. “The end.”

Bucky whined. “Telllll it, Lucius.”

“One morning Laurel and Hardy woke up. . . . The end.”

Bucky whimpered. “Looooo-shus!”

Somebody in Mammy’s room pounded on the wall. “Lucius, you all shut up in yonder!”

“Mammy, make Lucius tell me a story!” “You all pipe down now, or I’ll come in there with Gran’paw Charlie’s belt.”

“Momma!” yelled Bucky. “What’s you and Daddy whispering about?”

“We’ll put it in a milk bottle and give it to you in the morning.”

“In the old days of the West,” whispered Lucius, “lived a Mexican prince, and when it got dark, he turned into. . . Zor-ro! . . . The end.”

Bucky growled and kicked.

“Okay, Bucky, I’m going to tell this one. The moon was shining bright on the prairie and coyotes were howling on one of the buttes above Tombstone, when a lone rider appeared on top of another butte, like a shadow, against the big, big moon. And reckon who it was?”

“Zorro?”

“No.”

“The Durango Kid?”

“No. It was — Buck Jones!”

“Oh, boy!”

Anticipating Bucky’s reaction made Lucius giggle. “The end.”

Bucky let out a loud, body-wracking, throbbing cry-whine.

“I said, You’uns hersh!” yelled Mammy. “I got your momma squabbling with Fred in the living room and you all raising a ruckus in yonder.”

“Get under the sheet,” Bucky whispered in Lucius’ ear, his breath smelling of stale blow gum. Lucius pulled the sheet over their heads.

“‘While the Sea Remains,’” Lucius announced, and whispered some background music. “The Adventures of Sam Gulliver.”

“Oh, boy, you gonna tell the rest of it?”

“Remember somebody shot him in the belly.”

“And he woke up in a dungeon on this ship.”

“Yeah, and for weeks the only person he sees is this doctor. Well, the doctor wouldn’t answer any of his questions about Jonathan Crockett or the little man or the Indian in the cave, and he got so he was madder’n hell, so when his belly got healed, he got hungry for the smell of the ocean, being a sailor, so he called in one of the guards that stood outside his door. And all of a sudden the door jars open and this great big monster steps in, his eyes bloodshot with hate, a dagger in his hand ready to make sliced baloney out of Sam’s neck. Sam sees a chain and grabs it and slams it into the big guy’s chest and a swift kick in the jaw finished it.”

“Then what did the other guy do?”

“He come charging in wearing these brass knucks, and Sam threw him over his shoulder. He locked the door, then strolled down the deck just like he was one of the crew.”

“And then he dived off and swum back home.”

“No, too far out, so he decided to take his chances when they docked, if he lived till then. So he goes into the mess hall and starts talking to this little French cook. ‘Say, where we bound?’ ‘Africa.’ Then the cook turns around and his mouth falls open. ‘You a sailor on board, ain’t cha?’ ‘Yeah, why?’ ‘What cha got that bandage on for? You’re Wyatt Thorp. Get the hell out of here, you son of a bitch, or I keel you!’”

“Shhhhh,” said Bucky.

Lucius listened with Bucky under the sheet, then peeled it down to hear more clearly the yelling in the kitchen. Something crashed against the wall.

“Irene, that better not be one of my dishes!” yelled Mammy, from the bedroom.

“I have dishes too, Mother! Some things in this house are mine, you know.”

“Too many things! I wish you’d take what’s yours and move it out of my sight!”

“Don’t worry. I’d do it tonight if I had even a cardboard box to move into.”

“Till then, you’uns hush that racket. I got to open that cafe at the crack of dawn. Thanks to Fred and poor little Luke,” she began to cry, “they’s peace in all Europe and Asia, too, but not two minutes a whirl at 702 Holston Street.”

Bucky started whining. An ache in his throat, Lucius said, “Stop that bellering, and listen,” and pulled the sheet over their heads and patted Bucky’s shoulder.

“So, Sam just stood there, wondering who the hell Wyatt Thorp was, and why the cook called him that. The little French cook must of thought he was dangerous because he came at him with a butcher knife. But ol’ Sam grabbed his wrist and slid his arm around his neck and twisted his arm behind his back. ‘Say, what gives, Buster?’ Sam asks.

“It seems like ever’ time he asks a question, he gets clipped from behind. Which is what happened, and when he opened his eyes, it was a filthy sight. He was in the ship’s dungeon again. . . . Tune in tomorrow night for the next episode of the thrilling adventures of Sam Gulliver in ‘While the Sea Remains.’ This is WXOL signing off. ‘Oh, say can you see. . .Lucius stood up in bed and saluted, and Bucky smothered his giggles with a pillow over his face.

In this last episode, Lucius tries to impress Mammy, the expert storyteller, by telling her the story of a play he is writing.

Lord, Lucius, you sure you ain’t in some kind of trouble? Ever’body else is.”

“Naw, I’m just having trouble getting started on this play I’m writing.”

“A acting play?”

“Yeah.”

“What’s it about?” Mammy asked, absently, fixing chicken and biscuit dumplings. “Too bad it ain’t quite warm enough, we could eat outside under the mimosa. Did you see that marble table the Chief set up?”

“Yeah, saw it last Sunday. Looks good. . . . What do you think of my title?”

“Your what?”

“My title — of this play I’m writing. I named it ‘Call Herman in to Supper.’ Sound good?”

“Yeah, I reckon so.”

“It’s about this little boy named Herman, and he lives up in the Smoky Mountains with his momma and daddy and his gran’paw, who’s blind and deaf, but he can talk, see.”

“Lord have mercy, I meant to tell the Chief to bring some country butter on his way in.”

“And his daddy — whose name is Will —”

“That was my daddy’s name. . . .”

“I know it.”

“Now, listen, I don’t want you writing nothing about my family.”

“No, Mammy, it’s just the name. But he works in this coal mine, see. . . .”

“Well, my daddy wouldn’t go in a coal mine if you vowed to shoot him.” “But what he really wants is to be a farmer, like his daddy was.”

“Now, you’re gettin’ hot. My daddy owned half of West Cherokee at one time, had it all planted in corn.”

“Let me tell you, now.... So his wife — Cora’s her name — thinks she might have cancer.”

“She’s a goner. Ain’t no cure for it.”

“Except she’s probably pregnant.”

“Now, you hush that kind a talk in my kitchen.” Hurt, Lucius sat down at the table and played with the broken shells from the boiled eggs Mammy was shearing into the dumplings.

Shortly, Mammy said, “Is that all they is to it?”

“To what?”

“To the story.”

“No, it goes on to where it’s a day in the fall and supper’s ’bout ready, Cora’s fixing it, and Will comes in, and he ain’t found no job and they’re poor and hungry and all she’s got on the stove is beans, and Will starts talking mean about Gran’paw, ’cause all he does from morning till night is rock in the rocker and spit tobacco juice in a lard can, and when it comes time to eat, and he smells beans cooking, he calls for Herman to come lead him to the table. So Cora tells Will to call Herman in to supper.”

Mammy went over to the stove and fiddled with the candied sweet potatoes, and Lucius followed her and stood by as she bent over the oven to put the corn bread in it.

“And Herman doesn’t answer, so he says he’s gonna give Herman a whuppin’ for being late, and Cora says he better not be down there at the creek again. See, he’s just about four years old. And Gran’paw keeps calling Herman to lead him to the supper table, ’cause he smells them good ol’ beans cooking, and it bothers the fool out of Will. Will keeps talking about blowing up the mine, and it worries Cora, then he’ll threaten to shoot himself, then all of them —”

“Don’t, Lucius. . . .”

“He dreams of growing stuff next spring, and when Cora finds a bottle of whiskey in his pocket, he tries to get away from her as she comes at him with a stick of firewood for wasting what little money they got on moonshine, and she hits him with the stick where he’s got the bottle in the back pocket of his overalls, and Gran’paw smells it and whines for a swaller of it. Then Will gets worried about Herman, so he goes out looking for him, and Cora looks at herself in the mirror and talks to her daddy about when she was young and happy —”

“I thought he couldn’t hear?”

“Well, he can’t, but she just gets to talking to him — sort of to herself. . . . Then she gets out this wedding dress. . . .”

Mammy rattled coal from the bucket into the cookstove. “Chiefs gonna get me one of them ’lectric stoves, soon’s we get married. Boys, won’t that be the berries?”

“Want to hear the rest?”

“I’m listening.”

Lucius followed Mammy around as she moved about the kitchen, running water, stirring stuff in pots.

“Well, she looks at herself in the mirror and it starts her to crying to see how run down she looks.” “Them mountain girls go fast, honey. Your gran’paw Charlie took me over the Cumberlands to Harlan in 19 and 21 before the first railroad, and girls five years younger than me looked old enough to be my mother.”

“Anyway so — Really? I always like to imagine what it’s like in Kentucky. Did you see Trail of the Lonesome Pine?’

“Sure did, but it ain’t like that.”

“Oh. . . . Well, so, Will come back in, and he didn’t find Herman. And so they dream about things, how it might be if he was to plow in the spring, and then they fuss again, and ol’ Gran’paw cranks up to whine for Herman again, and then this neighbor of theirs, named Hank, comes in, and he sort of beats around the bush, but Will and Cora feel what it is he’s going to say, and —”

“Better not nothin’ happen to that little Herman, now. . ..”

“Well, wait and see — and so, he says, he was fishing down at the bridge and he saw something in the water, floating —”

“Now, Lucius, you hush.”

“Mammy, it’s just a story.”

“I don’t care! That poor young’un!”

“So Cora and Will run out to the car — it’s a old-timey T-model Ford — and Hank sorta ambles out, and it gets real quiet on the stage. .. .” Sensing the fear and sadness he had excited in Mammy, Lucius was thrilled, eager to make it show even more in her mouth and posture and gestures. “And then ol’ Gran’paw stops rocking, and he says, ‘Hermie, Hermie, boy, Gran’paw’s hungry.’ ” Imi tating the old man’s voice, Lucius noticed Mammy stopped turning the sweet potatoes and held a dripping fork, look ing at him, her mouth open, the heat from the oven making sweat burst out on her forehead. “Come on over, and lead ol’ Gran’paw tuh the supper table. Aw, man! Smell ’em beans, son? Ummmmph! Come on over, Hermie, boy, Gran’paw’s a-waitin’ to eat. Got good ol’ beans fer supper. Hermie. . . . Hermie, boy. . . .” And then he slowly leans back, relaxes, moans a little — as the curtain comes down."

Lucius and Mammy looked into each other’s eyes.

“For the Lord’s sake, Lucius, will you tell me where in this world you get sich stuff as that?”

“Oh, I was just walking down a railroad track past these ol’ poor people’s houses, and the sun was going down, and it was real chilly and I could smell the coal smoke, and I heard his voice calling Herman to come in to supper, and it just got me.”

“I never heared such a tale in all my borned days. Do you have to make it so sad? Can’t the little feller turn out not to be drownded after all?”

“That would spoil the whole thing.”

“You already got the story wrote?”

“Play. No, I sort of made up part of it as I was telling it to you."

“Then it ain’t too late to change it. Why can’t it be a log?”

“Why can’t what be a log?”

“That the man saw a-floating towards the bridge.”

“Oh, Mammy. .. .” Lucius drifted into the living room, sat on the flowered davenport, hunted for the book and the show pages among the Sunday paper spread out around him.

Tags

David Madden

David Madden is writer-in-residence at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He is the author of eight works of fiction; a Civil War novel is in progress. His grandmother died a month after he wrote this piece. He dedicates it to her memory. (1981)