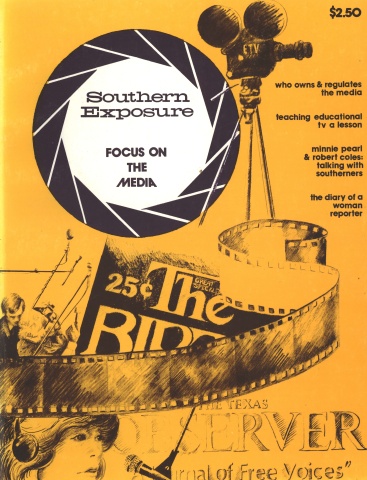

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Christ, I just don't know what should be included in a list of alternative media outlets. I really don't. I used to know. Once I was sure. But not any more.

In the spring of '71, I hitched around the South trying to decide which underground paper I could work with. I knew I would have to leave North Carolina, since the protean Radish had already folded, and I felt too much an outsider at Fort Bragg to work with Bragg Briefs. So I headed South. I knew where to go. First to Atlanta and The Great Speckled Bird, which since its '68 beginning had been the leading underground of the region. It was thriving, with a circulation still approaching 20,000. It blended news of national and international liberation struggles, with music and art reviews and a recently improved collection of local news and analyses. It was an angry, defiant paper, bitter and cynical, which took joy in itself and the people around it. It was a model for others. From there to Jackson and The Kudzu, New Orleans and NOLA Express, motive magazine in Nashville, a couple black papers, a few college radical publications, Gl papers. I knew where to go.

Terms like "alternative media" were never defined, but I assumed everyone sensed what they meant. You know, man, underground papers, like the Bird. Right? Everyone knew. You picked up a copy of NOLA, and it was filled with full page wavy-lined graphics covered in bleeding colors, and long prose poems wound in and out of the drawings. You knew it was an underground paper. The Daily Planet had a cover photo of the Florida governor slouched in a chair with his balls clearly outlined as they drooped into his pants. Kudzu described the latest attacks on their offices or staff. The Radish printed directions for the manufacture of Molotov cocktails. The Bird featured a long article about the Allman Brothers' free concerts in Piedmont Park with the statement. "There are times when it's easy to think that the rock and roll musician is the most militant, subversive, effective, whole, together, powerful force for radical change on this planet. Other times you know it's true." You know, underground papers. Right? Everyone knew. But of those publications I visited, only the Bird is left, and it has changed its orientation a half dozen times since it announced that rock music would lead to a revolution.

I no longer understand the terms. Now any paper occasionally to the left of the Democratic Party is described as "alternative." An FM radio station that simply plays rock album cuts instead of Top 40 singles is called "progressive." Does "alternative media" refer to the creativity of the staff or their radical political beliefs? The two rarely coincide. I know what I'd like the term to designate: outlets not dependent on business interests for survival. Staffs given the freedom to rely on their own creativity and interpretations and those of the people around them. A flexible format that allows for plenty of experimentation, in both content and form. Audiences willing to accept that flexibility without immediately switching loyalties. A willingness to open part of the outlet to whomever is interested. Honesty about the beliefs and concerns of the people behind the media. A news staff with time and skill enough to investigate news reports and social conditions with some thoroughness. According to that definition, though, there is absolutely no alternative media in the South. Nor in this country. Some papers and stations are simply closer to the ideal than others.

I.

A popular trend in weekly papers is to produce consumer publications that are virtually services for local businesses. Their pages are filled with long reviews: of restaurants, shops, movies, plays, concerts. Pages are filled with access guides to recreational facilities, bars, art resources, the best places to buy off-beat items. So much of the paper is filled with this that there is room for only one or two articles. Liberal or radical editors, who might have put out truly alternative papers (or once did), have found that this format allows them to squeeze in a few articles and reach a large, diverse audience. In addition, many editors have found that if they increase the press run and distribute the paper at no charge, they can more than make up for the lost sales revenue by the increase in advertising that will result. But, of course, that admits the power of the advertiser and identifies businesses as the final censors, for it is their money that totally controls the paper. A few papers are willing to accept that.

In Atlanta, The Great Speckled Bird is one of three papers vying for a young, white audience. At various times, it has been a youth culture paper, anti-war, anti-imperialist, feminist, gay, and muckraking. It never was, and still isn't a consumer publication. It is the only one of the three that isn't.

The main emphasis of the Bird recently has been on its local news reporting. Throughout a series of damning revelations about corruption within the city's police department, it was the main paper to write in-depth analyses and investigate the grumblings of people on the force. It was at least a week ahead of the dailies in much of its coverage. The Bird blends extensive city governmental reporting (many would say it is too extensive, and that articles are nit-picking and unbearably boring), brief descriptions of recent music performances, and articles of national and international events from left news services. It's a continuous voice within the city, frequently impressive, occasionally inaccurate, in its research. The quality of the paper varies with every issue, as the staff changes, volunteers emerge and disappear, people find time to complete a few articles or are rushed to finish several. But it is the only paper of the three which does not bow down to advertisers. Subscriptions and street sales account for a large percentage of its income (the other two are distributed free), and benefits, donations, and ads make up the rest. The staff receives subsistence salaries only when there is enough money on hand. It's an aggressive paper, the only one in the city with a sense of outrage, the only one ready to challenge governmental officials.

Creative Loafing, one of the other two weeklies, offers no writing of any substance at all, but makes no pretenses about it. It is simply an expanded calendar: more than half the pages consist of ads, the rest list upcoming events. But what it attempts, it does well. It is a comprehensive service and is frequently useful. Its restaurant reviews are especially good.

The Atlanta Gazette attempts to blend the two concepts, and succeeds in equalling neither the Bird nor Loafing. Like the latter, it attempts to review local activities, though it is not nearly as extensive. And like the Bird, it includes feature articles about Atlanta. But so far its only political view has been a vaguely liberal bent. It frequently stays away from political topics and includes cast¬ off articles that the dailies in town have rejected.

The Gazette does, however, include a column entitled "Ripsaw," covering local politics in a cynical, sarcastic tone. The pieces are pseudonymously authored and based on rumor and innuendo. But its main contributor is a long-time, extremely knowledgeable activist who applies years of political and personal experience in his native state to his writings. He is capable of writing strong, factual articles of political analysis, as he has for the Bird and on one occasion for the Gazette. But as a political gossip column, his writings cannot substitute for the expanded coverage necessary for a credible political section.

In format, neither of the two papers offers any competition for the Bird. But every week they each distribute 30,000 free copies around the city. The Bird sells only 7,000. Their music and culture sections are far more extensive than the Bird's. They have far more to offer those who run the music enterprises of Atlanta, who have for years been the Bird's main advertisers. It's no coincidence. Rick Brown, former advertising manager for the Bird and now one of the editors of the Gazette, said recently, "The record companies don't advertise with anybody but the Gazette. You haven't seen a record company ad in the Bird since I was its ad manager. I brought them with me. They looked at our paper when it first came out and said, 'This is exactly what we need. We're going to get behind it and support it.' They need a review medium. It helps their business."

II.

Jim Clark is director of the Ministry for Social Change in Greensboro, North Carolina, an organization attempting to increase communication among various groups in the city. In 1972, as part of that effort, Jim and the ministry began to publish a monthly newspaper, the Greensboro Sun, that is distributed free throughout the city. The Sun is one of the most un-polished papers I've seen. Lines are crooked, graphics are small and dark, objective journalism rules are ignored, and few articles read smoothly. It is definitely not published by professionals, and somehow in its lack of pretension, its honesty, its openness to people of many viewpoints, it's a refreshing paper to read. It doesn't claim to present the answers, doesn't suggest that it is the final word in journalism or analysis. But reading it is as enjoyable as listening to people who excitedly describe previously-unimagined concepts and newly-discovered friends. It's a community bulletin board for diverse groups in the area, and each eagerly presents its views and projects. Articles are personal and generally unrhetorical. A few scattered ads pay only for the printing; all editorial work is donated.

The ministry's interest in communications has now led it into another area of media: cable television. It started pretty simply. Jim Clark was sitting at home watching television. He says he does that occasionally to escape. “And I was watching 'Dragnet,"' he explains. “You know, the Joe Friday detective show. I couldn't believe some of the things that were being said. I mean it was offensive, straight out of the Nixon Administration! So I called the station to protest about the contents. The woman just sent me, to the Federal Communications Commission in Washington. I wrote them a letter and they said that with 'Maude' and 'All in the Family' on, they were giving equal time. But I couldn't buy that. I mean there are plenty of people who really dig Archie Bunker. And how does that combat images of freaks and gays and blacks that are presented?"

Soon after that Jim began investigating the steps for gaining control of a channel on the local cable network. "I was ready to fight. We were all set to take the local cable operation into court when they turned us down; we were ready to sue. But when we finally talked to them, they were just pleased to find people interested and ended up giving us the channel and this studio and a hundred thousand dollars worth of equipment." Jim stood in the new studio of CAT-CV6 (Community Access Television) which broadcasts 5-7 p.m. Monday and Wednesday nights. Two cameras faced a talkshow setting, with table and chairs before a curtain. A number of microphones covered the table and a nearby shelf. In the mixing room he inserted various tapes into a large machine and showed some previously recorded shows: a talk with members of the Venceremos Brigade, recently returned from Cuba; a puppet show produced by a local school; a discussion involving black Greensboro athletes.

Every local cable outlet is required to offer one channel for public access. With the help of the local Jaycees, one group ran the Greensboro public channel for four years, attempted some local origination shows, and then gave it up. They sold all their equipment to the sponsoring company. In the two years since then Clark and the ministry were the first to ask about the possibility of using it. Local cable officials helped them prepare a board, taught them to use the equipment, and are paying much of the operating costs.

"When we began, we sent out letters to every group in the city which we thought might be interested, offering them air time. So far groups like the U.S. Labor Party, the AFSC, the ACLU are the main ones to take advantage of the offer. But we don't want to be identified as a radical channel. We don't want to be branded like that, and turn people off immediately. We're hoping to have programming of local bird clubs, maybe, of Y's, of churches, you name it. Really make it a community station. The radicals are just part of that community. We definitely want them to have access, but not just them. There are plenty of other groups that can't get on private TV. We want to do with the station what the Sun accomplishes: public access media. It's a powerful tool. We want to open it up to everybody."

III.

Though in many parts of the South cable television is a relatively new phenomenon, in the mountains of Appalachia cable has transmitted national network broadcasts for the past twenty years. "In fact," claims the 1975 catalogue for Appalshop, "National TV has done more to change (and perhaps destroy) the Appalachian culture than anything else in the last 200 years." Appalshop (P.O. Box 743, Whitesburg, Kentucky 41858), a rapidly expanding mountain media group, attempts to offset some of that national programming with its own cable presentations on the public access channel. Four hours a week Appalshop broadcasts music shows, children's programs, local sports, news, and the group's own films. In addition, their catalogue explains, "a system of trading videotapes with Broadside TV in Johnson City, Tennessee, has brought in a series called 'In These Hills,' which features such aspects of mountain culture as herb gathering, music and midwifery, and provides further exposure of our own tapes." Like the Greensboro access station, the Appalshop staff maintains that they provide "open access to anyone who wants programs televised."

But cable is just one of many projects being pursued by the group. It was originally begun as a film production outfit, and that is still the staff's most noted enterprise. They have made more than two dozen films and are now at work on a feature length production of Gurney Norman's Divine Right's Trip, the novel originally serialized in The Last Whole Earth Catalog. As in all their work, Appalshop's film division has two main goals: to involve the people in the surrounding mountain area in their work, and to present an accurate picture of the region. Their cameras capture individuals at work — midwives, moonshiners, butchers, farmers, musicians - and probe political issues. Two years before the presidency of the United Mine Workers was taken from Tony Boyle, the group made a film identifying mine workers' complaints, and shortly after the Buffalo Creek mining disaster of 1972, Appalshop crews arrived to produce what has become a devastating expose. Their films contain political commentary, investigative reporting, and present sensitive portraits of a culture.

Besides cable, Appalshop has expanded into other areas: a theatre workshop, recording studio for producing traditional Appalachian music, and The Mountain Review. September, 1974, marked the first issue of the quarterly Review, featuring both previously-published and unknown contributors. It included photographic essays and articles on religion, music, politics, media, and education. Single copies sell for $1.50, annual subscriptions for $5. Considering the work of editing the Review, preparing it for publication, printing copies, and distributing them (I don't know if contributors are paid), the cost is reasonable.

But that points out one of the ironies of these alternative media outlets. Media is an expensive field. How many Appalachian homes can be expected to subscribe to the Mountain Review? Not many, I suspect. Appalshop (like most quarterly publishers) probably exists to gain sales primarily from libraries, not individuals. The print medium, after all, is inherently elitist. Who does it reach? A still significant number of people are illiterate, especially among the working class to which so many alternative media projects claim to direct their material. Do a majority of the people in this country even enjoy reading? I doubt it. And who can afford it? Even should they want copies, most households must consider quarterly literary publications as unthought-of luxuries.

Printing is an expensive process. No publisher or print shop can change that. Yet it is one of the most accessible media forms of all. Certainly one of the least expensive. The Greensboro cable station—which cannot yet film outside the studio —has a minimum amount of equipment: $100,000 worth. FM radio station licenses (if obtainable at all) can rarely be bought for less than that price. AM radio licenses are even more.

IV.

One way a radio station might avoid the massive expenses of buying a license is by incorporating as a non-commercial station. No cost. The only requirement for such a classification is that no advertising may be aired. Without ads, however, income to run the station must come from elsewhere. Most often, stations in this situation are supported by the sponsoring group, usually a university. Two non-commercial stations in the South, however, have chosen a different group on which to rely for their funding: their listeners. The two are WAFR-FM in Durham and WRFG-FM in Atlanta.

WAFR, begun in 1971, is the only black owned and operated public radio station in the country. It broadcasts a blend of jazz, gospel, blues, and other black-oriented music. African music is played, with each piece described by an African student from nearby North Carolina Central University. Durham high school students have their own show; the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People presents a series on local political issues; speeches given at NCCU are taped and rebroadcast; local Muslims provide the station with tapes of "Muhammed Speaks.”

"We've been the kind of station,” explains station manager Obataiye Akinwole, "that a brother would come to. There's one brother in particular who plays a very nice blues harmonica. He'll come up here and pull his harmonica out and say, 'Can I blow, man?' I'll turn the microphone around and say, 'Go right ahead.' We'll record it while he's blowing; he'll sing some blues and whatnot. And that's a nice little show.” The radio station is that flexible, that open to the input of individuals within Durham's black community.

Although the station is occasionally described as listener-supported, and in fact it receives more support from its audience than most stations, contributions actually account for a small fraction of the WAFR budget. It has received a number of grants from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to buy equipment, from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, from the Inter-Religious Foundation for Community Organization, and others. Benefit concerts have been staged to raise money, a 168-hour marathon broadcast netted $10,000, and two years ago a group called Friends of WAFR was organized to seek extra funds from the surrounding community. Thou¬ sands of dollars were contributed at cocktail parties, fashion shows, and a beer bust.

Atlanta's WRFG also continually sponsors benefits — everything from concerts to barbecue dinners in the backyard of the station. The staff prints a monthly program guide which is sent to subscribers. But the budget for WRFG is considerably below that of WAFR. It has received no grants. Including the salary for the program director, the only paid staff member, $800 is spent each month. Soundproofing consists of walls covered with egg cartons and long curtains. But from the station comes some of the best jazz, blues, gospel, folk, and bluegrass programming in Atlanta. It offers the most complete coverage of City Council meetings and some other local news of any station in the city. Its schedule easily includes the most political commentary of any station, which is often presented clearly and honestly. Commentary peppers most of the musical programs. The station provides studio space for community groups who would like to produce a show. The result is a varied schedule, in both musical content and commentary. Yet WRFG remains loose enough to feature its own street blues harmonica performer who wanders into the studio at various times and is put on the air.

Both stations, however, have recently been crippled by controversies. WAFR has become embroiled in a dispute between the president and station manager of the station, and the Board of Directors. The two staff members have fired the Board and attempted to replace it with another; the Board has tried to fire the president and, when he refused to leave, has taken the issue to court for a declaratory judgement concerning just who actually does control the station. The Board claims they have no criticism of the station's programming; Obataiye Akinwole, the station manager, disagrees and says the Board hopes to eliminate all political programming. If the courts determine that the original Board has control, says Akinwole, “We're dead. This station is dead."

Board members maintain that the only point of contention involves the management of the office. Over the years a number of suits have been brought against the station for payment of numerous debts. The staff has been lax in its attention to many FCC regulations. Elections for the two top positions at the station, required by the by-laws, have not been held since WAFR first went on the air. Akinwole, who admits the station owes $15,000 despite its many grants, claims these problems will be taken care of. "We've got a plan that's going to take care of all that, that will bring in professionals for the key jobs. We'll take care of that," he says.

"They've said that for a long time," responds one Board member. "The court case should determine if we on the Board are responsible for the debts of the station. If we are, we'll have to make some changes concerning internal business practices."

The situation was further complicated when the station went off the air on December 26, 1974. Station president Robert Spruill claimed WAFR would resume broadcasting after a three week absence. "We just need a little time to raise more money," he says. "Lately all we've gotten have been the kind you or I could give: $10, $15. We want enough to run this station the way it should be. We're looking for big money. Grants."

One grant, in fact, has already been made. HEW has earmarked $62,000 for new stereo and automation equipment, which will be paid when the courts determine responsibility for the station.

In Atlanta, WRFG has run into its own difficulties. It originally broadcast over 18 watts (now increased to 1250) from an antenna placed on television station WQXI's tower. In mid- September, 1973, WQXI told the radio station to remove its antenna, claiming that it interfered with television transmission. WRFG personnel say they have checked with a number of engineers and have found no reason to think any interference could have taken place. They have also discovered, however, that shortly before WQXI's decision the general manager of the station was visited by a pair of detectives from the Atlanta Police Civil Disturbance Unit. That same unit was thought to be investigating the station and its involvement with "subversive" political groups. They are convinced that the police detectives' visit triggered the station's decision to demand that the antenna be removed. The general manager claims he was not persuaded and that the visit simply reminded him of WRFG's interference. The station eventually erected their antenna on a 50 foot mast on the roof of their studios. At that height, transmission was blocked on one side by a school building, and on another by a large tree. Only after weeks of searching for a new location did Clark College agree to allow the WRFG antenna on its tower.

V.

And there are the special media projects that defy description and categorization — like the Texas Observer and Southern Patriot, probably the longest continually published alternative papers in the South.

Begun in 1942, the Patriot is the monthly organ of the Southern Conference Education Fund, or SCEF. It is a source of information and copy for many of the alternative papers, for despite its zealousness it provides the only in-depth coverage of many southern political conflicts, including strikes, demonstrations, and arrests. It is especially concerned with organizing efforts among poor black and white people and with multi-racial union drives. And it is consistent in its coverage. When the Patriot gives space to an issue, it stays with it. If a demonstration is mentioned, the events leading up to it have usually been described at length and the results will be covered in a future issue.

Twenty years ago, the liberal wing of the Democratic Party in Texas started a paper. The first issue, edited by Ronnie Dugger, was critical of the liberals; the party demanded that the paper step into line, Dugger refused, and the Texas Observer became an independent publication (see more detailed discussion in Larry Goodwyn's article in this issue). It has remained so ever since. Like most alternative papers it has led a metamorphic existence, depending on the staff and its interests. It has covered the Texas legislature and the University of Texas, attacked the oil powers, supported the civil rights movement, proffered a southern consciousness, espoused feminism. Over the years the Observer has come to represent the richness of the state in its format and has virtually stood alone in struggles against the moneyed and powerful.

Yet like the best of the alternative media, the Observer's circulation has never been especially large. Now it has waned even more as it has come into competition with one of the most successful new slick magazines, The Texas Monthly (P.O. Box 1569, Austin, Texas 78711). An award winner as the best regional magazine in 1974, the Monthly has taken the popular consumer format for newspapers and has applied it to magazines. It's fantastically successful in terms of circulation (over 300,000 after its first year) and advertising. Every issue features more than 120 pages. Dozens of pages are spent describing activities in the state's largest urban centers, comparing stores and restaurants, identifying recommended shopping sprees. Along with this are one or two extensive political articles, many of them well researched and written. It may not be "A Journal of Free Voices; A Window to the South" as the Observer's masthead claims, but among mass-circulation slick magazines it is impressive.

From its Clintwood, Virginia, base, the Council of Southern Mountains publishes a monthly newspaper entitled Mountain Life & Work. Much of the paper is given to descriptions by local people of the activities of the Council's constituent groups; the rest is made up of feature articles about life in the southern mountains, from social gatherings to political controversies. Topics are covered thoughtfully, as seen in an entire number on the lives of mountain women. The issue stayed away from strident rhetoric, from the charges and challenges of big city feminists, and instead produced a warm, strong, and insistent publication that educates without indoctrinating, and provides enjoyable reading as well.

In North Carolina, one of the South's most unique alternative media outlets exists in the home of the Durham branch of the Southern Africa Committee. Years ago the Committee, a research group supportive of African liberation struggles, decided to decentralize its work, and a group of staff members moved South. A few months after they arrived, they began to publish "Africa News" (P.O. Box 3851, Durham, NC 27702), a news service that provides subscribers with the only inexpensive source of extensive and continuous reporting of African events. Twice weekly, the "News" staff prepares approximately 10 pages of news and features reports from a variety of sources, including special correspondents, dozens of African publications, and the BBC. They currently supply about 40 papers, broadcast stations, and libraries, with their reports.

VI.

Dozens, hundreds of alternative groups are scattered throughout the South. They're often found in the seedier parts of town. The offices are not panelled, nor carpeted by Bigelow. Equipment is old and breaks down regularly. Many of the staff live nearby in the same low rent buildings in which they have set up their businesses, their media outlets. Storefronts on secondary streets, nestled between dry cleaners and locksmiths. Walk-up offices with broken windows. A back room. Second-hand furniture that was cheap when it was new. In the winter they're cold.

The people who work in them do so for their own individual reasons. They include a great many volunteers who help when they can. People who have always been fascinated with media perhaps. They have political beliefs that they want people to hear, and need a means of reaching others. They're looking for new art forms. They seek to avoid the limited responsibilities and freedom they might find at the better financed stations and publications. Some are ego-tripping. Few of them know whether this is their life's work. They don't set up institutions from which they can expect years of employment. They take risks.

And more keep springing up. Alternative papers. Movement print shops. Progressive FM outlets. Community access cable franchises. Quarterlies. Film groups. Theatre. Dance. Bands. More than we could ever mention, even more varieties than we can cover here. Few of them break even. Even fewer expect to turn a profit. Occasionally they produce the most innovative and powerful work being done in media. They persevere, forever begun by those with vision, with a message to deliver, with a desire to communicate as much by their own rules as possible. Dozens arise and dozens fall every year, as they always have and will.

Tags

Steve Hoffius

Stephen Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, South Carolina. For a year he edited the state newsletter of the Palmetto Alliance. (1984)

Steve Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, and a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1979)

Steve Hoffius is a Charleston, SC, bookseller and free-lance writer. (1977)

Steve Hoffius, now living in Durham, N.C., co-edited Carologue: access to north carolina and is on the staff of Southern Voices. (1975)