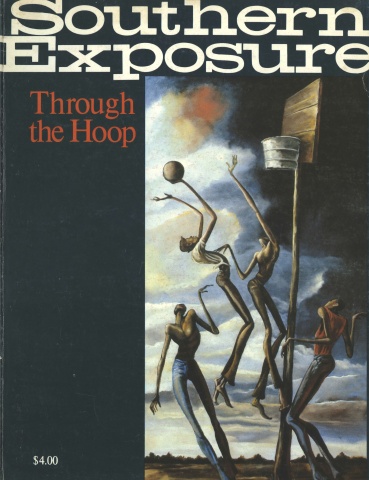

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

“I love action. I love fighting. I just ain’t big enough. If I was, I’d be in there with em. I belive it’s mostly fake, about 75 percent. They get mad at each other every once in a while, but I think a lot of it is strictly put-on. But I just like the action, just to see em get whupped, the bad ones. I’m here every week. This is my reserved seat right here. ” - Mike Broughton, professional wrestling fan from Wetumpka, Alabama

DOTHAN, ALA. - This is the wiregrass region, gently rolling farmland with sandy soil and a tropical sun; the Gulf of Mexico is only 90 miles away. Peanuts are the main crop, and the National Peanut Festival is celebrated here every fall. Many of the region’s people still make their living farming, and on Friday nights they may come into town to the Houston County Farm Center for an evening of entertainment.

The Center is a giant barn, windowless, unair-conditioned and hot. On two sides, banks of concrete bleachers reach to the roof. The center of the arena is open, with a dull red-dirt floor mottled by tobacco spit and spilled Cokes and littered with cigarette butts and peanut hulls. A layer of blue smoke drifts across the room. Several rows of folding metal chairs are arranged in a square out on the dirt floor. This much of the setting is drab — concrete, dirt and metal. All the color is concentrated in the middle of the arena, in a wrestling ring of blue canvas and red, white and blue ropes, brilliantly lighted by a row of television lamps.

For 18 years, the farmers from the Dothan area have been coming to this ring on Friday nights to watch professional wrestling; in the years before that, reaching back to the 1930s, they came to older arenas. Part athletic competition and part soap opera, pro wrestling is the only sport many of these fans know, and they are intensely loyal and enthusiastic. The Farm Center will seat about 5,000 fans, and on a May night earlier this year, 1,500 more who wanted in to see Andre the Giant — 7’4”, 485 pounds — were turned away at the door by fire marshals. The fans had come that night to cheer Andre, whom some call the Gentle Giant, because he is a good guy. In the wrestling ring, good and evil are distinct, and the fans pour into the arena to cheer the good guys and to jeer and curse the bad ones.

Generalizations are dangerous, admits wrestling promoter Dick Steinborn of Montgomery, but “it is mostly your blacks and your poor whites who come out here.” On a given night the audience may include a handful of white-collar types, such as Houston County Probate Judge R. J. Stembridge, a front row regular, and the two women from Panama City, Florida, who drive up every Friday night, come to ringside wearing evening dresses, check into the motel where some of the wrestlers stay, and spend Saturday poolside chatting with the behemoths who were pounding opponents in the ring the night before. But these are exceptions, and the average wrestling crowd is made up of the kind of working people whose pickups in the parking lot wear bumper stickers with messages such as, I FIGHT POVERTY, I WORK.

Dothan’s fans are probably typical in these respects, and nationally millions more share their passion. The National Wrestling Alliance claims that for the six years from 1972 to 1977, professional wrestling drew 219 million paying customers. In that same period, the NWA says, college football drew 198 million; major league baseball, 195 million; pro football, 83 million; and pro basketball, 57 million. The wrestling season, of course, is 52 weeks long, and matches are promoted in countless towns and cities so small other sports would never give them a second thought. An estimated 60 percent of the national attendance is in the South, in arenas like Dothan’s.

The price of an average wrestling ticket is $4, and the annual paid gate for the industry is estimated at between $100 million and $150 million. Whether sport or entertainment, professional wrestling is big business. It is also a closed business, in many ways a family business. At one time, promoters in almost every city in north Alabama and Tennessee were related by blood or marriage, and many of the wrestlers and promoters active today got into the business through their families or in-laws.

Dick Steinborn, for example, is the son of Milo Steinborn, who is a living legend in the wrestling world. A German, Milo went to sea as a young boy and was in Australia when World War I began. He was interned there with other German nationals in a prisoner-of-war camp. There was nothing else to do, so the men organized themselves into prison intramurals. Every day, the prisoners wrestled and lifted weights; when the war was over and Milo Steinborn was released, he was a perfectly proportioned and perfectly developed young man of tremendous strength. In 1920, he stowed away on a ship for New York City and eventually made his way to Philadelphia, penniless and friendless.

In Philly one day, Milo visited a gym where a weight-lifting contest was in progress. Milo realized he had been picking up more weight in the POW camp than these world champions were handling. So he entered the competition and astounded the other lifters, the spectators and the press, which had a field day with the man off the streets with the superman strength. Milo Steinborn was discovered.

The giddy ’20s and depressed ’30s were years for spectacles, and entrepreneur wrestling promoters were always looking for new attractions. Milo Steinborn, the young superman, was enticed into wrestling, and it soon made him wealthy and famous. In those days, big-name wrestlers, like the great boxers, got their names and pictures on the front pages of the newspapers, reporters met them at train stations, and they made lots of money, sometimes 50 percent of the house — Madison Square Garden was selling out for wrestling even at the worst of the Depression. It was a business of handshake contracts and cash payoffs. Milo would be standing at the dressing room urinal when the promoter came in, stood at the urinal next to him, and peeled off $1,200 for a typical night’s work — a new car sold for $700 then.

The promoters were also looking for new markets, and there were none more promising than in the South. Big names like Milo Steinborn drew the fans in, and he became well-known in Richmond, Charlotte, Birmingham and Nashville. In Atlanta, he met and married a Southern belle who came with her sister to watch him wrestle. Her name was Vivian Baxter, the daughter of a plumbing contractor.

Milo and Vivian had two sons, Henry and Dick. Both became successful amateur wrestlers, won scholarships to Columbia University in New York, and lived and breathed the world of professional wrestling. Later, after the father had retired from the ring and taken up promoting in Orlando, Florida, the sons learned that, too. (When Milo retired from promoting — in 1979 at age 86 — Henry also got out of the business. He is now a professional musician.)

Dick was the son who loved wrestling, loved the stink and sweat of filthy dressing rooms, and, like his proud German father, loved the discipline of the gymnasium. Dick is 45 now, but on a Saturday morning in Dothan, he will be in Garry’s Gym, working out with other wrestlers and offering a local kid his technical advice and anatomical knowledge. A Steinborn workout tests and exploits every major muscle in the body. Sweat pours from him as he works out on the bench, and one notices the peculiar breathing pattern of the weightlifter: suck the lungs full, grunt the weight up, explode the breath out at the peak of the lift. The idea in building strength is to take the muscles to their limit and a little beyond in every workout, stretching the muscle fibers so that next time they can do just a little more.

The fact that some wrestlers work out regularly and vigorously while others don’t makes it even harder to answer the question most often asked by non-wrestling fans: Are these guys athletes or entertainers? A fair answer is that they are both, that most of them have the skills, stamina and strength for legitimate wrestling. But the wrestlers say that the fans, especially in the South, want to see “catch as catch can” competition, replete with exaggerated falls, wild punches and frenzied action.

“A wrestling fan is not like a football fan,” says Ox Baker. “They are more vicious, more sadistic. They want to see the bad guys out there ranting and raving. They won’t come to see anything else. You can have the NCAA finals in college wrestling and you can’t even get a crowd; it won’t even make the papers in most places. People want action and we’re professionals, we’re geared to it, so we give it to them. But when there’s blood out there, it’s real blood, it’s our blood. I’ve had teeth knocked out, my knees are boogered up, my wrist has been broken — and I’ve had a chair broken over my head by a fan.”

(Fans can do worse. In Hogansville, Georgia, one night, a fan leaped into the ring and stabbed wrestler Sonny Myers with a knife. In the words of another wrestler, “He stuck the knife in Sonny and then walked around him.” Myers survived; he is now a wrestling referee in Tampa, Florida. Steinborn was attacked once by a senior citizen wielding a cane. He suffered severe cuts to the head, but retaliated by punching the old man out.)

Still, Baker acknowledges that there are limits to the slugging wrestlers can do to one another night after night. “We do have agreement among ourselves. Wrestlers know they have to restrain themselves.” Wrestlers say this means not that matches are prearranged and rehearsed, but that to fit the schedule and to please the crowd the wrestling may be mixed with soap opera. “Say we’re on TV and it’s an hour program. Now I can beat my opponent in 45 seconds,” says Baker. “But the promoter may tell me, ‘Ox, I need seven minutes.’ So I’ll entertain the people for seven minutes before I put the man down.”

Wrestlers also have an incentive to win consistently and to build up a reputation because their earnings depend on it. A wrestler can do preliminary bouts every night and he may earn as much as $40,000 a year if he is willing to travel enough. But a main event wrestler like Ox Baker will earn $300-$700 for 15 minutes of work at the Houston County Farm Center; before a bigger crowd his evening’s pay may run as high as $2,000.

It is the money, Baker says, that is in the back of every wrestler’s mind when all the ranting and raving and posturing for the crowd has ended. “That’s why wrestlers don’t get together after matches. We’re like magnets coming at each other and the fans wouldn’t understand it if they saw us later being friendly.” At the Farm Center, for example, there are two dressing rooms (with the word “White” painted out but still visible over the door to each) and the “good guys” use one and the “bad guys” use the other. The wrestlers who stay at the Sheraton Motor Inn in Dothan all take rooms on the same wing, but a “good guy” generally will associate only with other wrestlers of the same image.

Some wrestlers, then, work out and stay in shape and try to get stronger so they can be more effective in the ring and at the bank. Some work out because they like it. Back at Garry’s Gym, Steinborn’s face is twisted with pain as he finishes a “set of reps” and leaps up. “The body wants it, the body says ‘thank you’ every time you do it, the body loves it,” he says.

Across the room, Terry “The Hulk” Bolder is in pain, too. He is sitting on a bench with his arms on a little padded shelf built for curling. Terry has reached the sixth of 10 repetitions in this set of curls, and he is almost crying in his effort to finish. Wrestler Ron Slinker, Bolder’s friend and road roommate, is counting, yelling encouragement and standing ready to take the weight if needed.

Weightlifting can be done to increase strength or to increase what bodybuilders call “definition,” or the prominent appearance of the muscles. Bolder does a little of both. Steinborn’s chest, arms and thighs ripple with hardness and power, but Bolder’s body bulges and swells with knots of muscle. During his workout, Bolder constantly watches himself in the mirrors which lines the gymnasium walls. He flexes his great tanned body and studies it, deciding which exercise he needs to do next to bring out some muscle not quite as defined as the rest. His body and his ring nickname, The Hulk, are Bolder’s trademarks, and they have made him a crowd favorite and a main event wrestler in only four years. The sign outside the Farm Center flashes with his name: “Tonight — The Hulk vs. Ox Baker.”

Terry is 6’3” and weighs 300 pounds. His blond hair is shoulder length and he wears a sweeping mustache. The hair on his chest is shaved into a geometric pattern which tapers to a point and disappears into his wrestling trunks. In the arena before his matches, Terry will stand in the corridor near the dressing room, surrounded by young women, some of them girls, really, who flirt with him and who sometimes reach out furtively to stroke the muscles in his arms and back.

“Young girls come up and say, ‘How can I marry a wrestler?’ They think the wrestlers are gods, they really do,” says Sheila Steinborn. “You wonder if your husband pays attention when these women get dressed up in their Sunday best week after week and sit at ringside hoping to be noticed. But that’s just part of the business. The older guys are used to it. It’s nothing to them so they let the young guys get the glory. But the ones who are just getting in the business, sometimes it goes to their heads. You wonder how well they can handle it.”

Wrestling wives must also cope with the pressures of frequent moves and the regular absences of their husbands, sometimes as much as four or five days a week. The wives of athletes in other sports — baseball, for example — frequently band together for support, but Mrs. Steinborn says that rarely happens with the wives of wrestlers. “I finally learned to make friends with neighbors. At first I wouldn’t want to say what Dick did for a living, because you never know how people will react. In the dentist’s office, even, when you have to put down your husband’s occupation, I’ve had them look at me as if they were saying, ‘Oh, one of those.’ But once people get to know Dick, they find out he’s just like anyone else.

“Wrestling has been good for us. The traveling and getting to know people and other places may be the best part. Sometimes I wonder a little if wrestling may have held Dick back. I wonder what he could have done with his energy and ability in other things — and Brad [the Steinborns’ three-year-old] loves wrestling! You want your son to be a doctor or a lawyer, not a wrestler. But Dick loves wrestling. It’s his life,” she says.

There are thought to be about 3,000 professional wrestlers in the United States, and only a handful of new faces break in each year. Those who do usually make it with some kind of gimmick, like Bolder’s body and his cultivated “good guy” image, to attract either the adoration or the hatred of the fans. It doesn’t matter which, because both sell at the box office.

A good promoter instinctively knows what will sell and when to introduce something new. Steinborn, for example, has found a pair of strapping black twins. Because they are black, they will go over well in heavily black south Alabama, and because they are polite and have “good guy” images (partly because they are matched against known “bad guys”) they will be popular the white fans as well. And in Dothan, Steinborn has been opening the card in recent weeks with a “challenge” issued by a young wrestler named Herb Calvert, who is trying to break in.

Calvert has offered S500 of his own money to anyone in the audience who can stay in the ring 10 minutes with him. A former standout at the University of Oklahoma, Calvert was an Olympic-class amateur wrestler before he left college to turn pro. At 6’4” and 255 very solid pounds, he could be expected to scare away anyone who has had a good look at him. Two fans at ringside on this night are recalling how Calvert rubbed a challenger’s nose on the canvas until the poor guy gave up last week. Two weeks earlier in Montgomery, he broke a man’s arm.

Still, 10 eager applicants line up, and Steinborn herds them off to the side. “All right, fellows. Now I’m going to pick three of you, but before I pick listen good. This paper is a release form. It’s two pages of legal stuff and I’ll read it if I have to, but I won’t bother as long as you guys understand that it means you can’t sue me, this building, Herb Calvert or anybody else if you get hurt or killed.”

Everyone nods and Steinborn quickly picks the three challengers who appear to be the stoutest of the lot. They are David Matthews, 21, 245 pounds, a farmer; Joey Matthews, 22, 202 pounds, a mechanic; and John Hagans, 19, 260 pounds, a student. None is taller than six feet. Steinborn gives them a final warning: “No biting, no trying to pull his eyes out, no punching. You try any of that and you’ll release the animal in friend Herb.” David and Joey have serious looks, and John looks as if he wonders what he is doing here.

David lasts 45 seconds before giving up. John lasts only 30. Joey is agile and mobile and quite strong and Calvert works him for three minutes. At the back of the arena a man in overalls, his face leathery from the sun, cries out encouragement to his son: “Hold ’im, boy!” Joey does hold on, but Calvert quickly maneuvers him into what the wrestlers call a “sugar” hold. Steinborn climbs into the ring with the microphone and shoves it right up next to Joey so that the crowd can hear Calvert shouting “Give up?” at him. Joey is stubborn and he hears the crowd cheering him so he mutters “No” a few times, weakly, before finally submitting.

Three nights later in Montgomery, Calvert will demolish two more challengers, and pro-wrestler Ron Slinker, a crowd favorite, will show up at ringside with $500 of his own money asking Calvert why, if he’s so tough, he won’t take on another wrestler. But the audience challenge is Calvert’s gimmick, and he is making the fans hate him, which is a guarantee that they will pay to see him. Calvert brushes Slinker off, and as he leaves the ring the fans are on their feet, some of them right in his face, calling him a coward and worse. Calvert snarls at them, asking why they don’t get in the ring with him. As the abuse mounts, Calvert turns to the crowd and roars, “I love it!” Two policemen escort him from the arena, but a young black man follows screaming insults. Finally, Calvert turns to him and yells, “I want you. Why isn’t your black ass in there? I want you!” The young man laughs and runs back to his seat; his friends slap his hands and laugh with him.

But that is in Montgomery. On this night in Dothan, the three challengers, despite the ease with which they were defeated, are congratulated by others in the crowd. Joey Matthews joins his buddies in the stands, and one, grinning broadly, speaks up: “Hell, boy, why didn’t you call me? I’d a throwed you my knife or pistol or something. Shit. We could’ve used that $500 in the race car. Could have bought a new radiator. You gonna try him again next week ?”

“I’m seriously considering it,” Joey says.

“Well, I’ll work you out all week so you’ll be in shape this time, boy. Shit. I’m thinking about trying that mother myself.”

Whether Joey or his friend wrestle Calvert next week doesn’t matter (in fact, neither does) because there will be other fans who will, and the rest will be screaming for them. Calvert excites the fans and that’s what they pay for. Keeping the fans excited week after week, however, takes more effort than it might seem. This responsibility belongs partly to the promoter and partly to a “matchmaker,” who is employed by the individual or group sponsoring the matches in a region. In the case of Dothan, that group is called Gulf Coast Championship Wrestling, and Dick Steinborn, who owns Montgomery and oversees operations in Dothan, is one of the promoters who owns a percentage of the action. Dothan and Montgomery are two of the seven Alabama and Florida cities on the Gulf Coast circuit. It is the matchmaker’s job to decide which pairings of wrestlers, because of reputation or chemistry or whatever, are likely to please and excite the crowd.

Because basically the same dozen or so wrestlers will be competing against each other in Dothan tonight, Montgomery two nights later, then Mobile and so on around the circuit, and then repeating it next week, the pairings have to be adjusted to maintain interest. Once the matchmaker gives out the assignments to the wrestlers, it is up to them to build up as much interest as possible before the match and then to make the match itself as exciting as possible.

The pre-match buildup is accomplished partly with a one-hour television show taped each Saturday at a Dothan station and then shown in each of the cities on the circuit a couple of days in advance of the live wrestling. The promoters pay for the television time, and the hour will include some wrestling and a generous amount of interview time in which the wrestlers describe what they are going to do to their opponents next week.

The matchmaker will also try to bring in outside wrestlers like Ox Baker (who is from Texas) to increase attendance. Baker is well known around the country partly because of his size and strength — 6’5”, 318 pounds — and partly because of his legendary heart punch, with which, the promos say, he has killed two wrestlers.

Baker is the picture-book bad man. “I was not the best-looking guy in the world, see. So the fans were going to dislike me from the beginning and I figured why not take advantage of it,” he says. So he shaved his head and grew a mustache which makes him look even fiercer, and he cultivated an image as a killer. (He also has pink painted toenails, but to know it a fan would have to visit the Ox’s hotel room while the big guy was sitting around in his boxer shorts eating pizza.)

“I don’t really believe he killed those wrestlers,” says fan Mike Broughton. “Think about it. Would they let him keep on wrestling if that had happened? He better watch out tonight, though. Terry has got a heart punch of his own now.”

One of Baker’s two alleged victims was Ray Gunkel, who died after a match in Savannah, Georgia, in 1973. Ox Baker says, “It was a hard match and he broke my wrist in the course of it. He died right after the match. The autopsy showed he had received a vicious punch to the heart.”

But Savannah promoter Aaron K. Newman was with Gunkel when he died. “Ray won the match, you know. It was a brass knucks fight [in which the wrestlers’ fists are heavily taped] and it lasted seven or eight minutes. He came out and went to the dressing room to take a shower. After that he was sitting in a chair, nude, asking about the house, about how well we did. He didn’t seem to be acting just right. He had eaten real heavy that day about two p.m. I asked him if anything was wrong. He put his hand up to his chest and heaved sideways. Ray just had a massive heart attack. He was 48 years old.”

The other wrestler who died after fighting Baker was Alberto Torrez, in 1970 in Omaha, Nebraska. Torrez had been warned by doctors that continued wrestling was a great risk for him because of a pancreatic condition. In the match with Baker, he received a blow to the pancreas; he died four days later.

Newman thinks it is wrong for Baker to capitalize on the coincidence that two wrestlers died after matches with him, but the Baker image nevertheless lives on. Wrestling is a sport which depends on image; it may matter to the wrestlers themselves whether they win or lose, but the fans stay loyal regardless. Psychologists periodically publish treatises on the symbolism and ritual significance of football, but it is professional wrestling which is really a modern morality play. If the good guy wins his match, that is simple justice, and if he loses, that’s life.

Baker probably couldn’t change his image if he wanted to because it is so well set in the minds of the fans. Mellonee Kapner of Daleville is 67 and has been an institution at the Dothan arena for two decades. She gives Ox Baker hell from the minute he enters the arena. She gets up from her ringside seat and walks up right next to the ropes, calling Baker profane names — names she would never utter outside this arena — until he leans over the ropes and shakes his giant fist at her. The sight is almost comical: the huge man towering over the little white-haired woman. Later, Mrs. Kapner is telling some other people what she thinks of Ox Baker.

“You know, he’s killed two men,” she says solemnly.

Tags

Randall Williams

Randall Williams is a fugitive staff member of the Institute for Southern Studies. He is currently living and working in north Georgia, where he is guiding the start-up of two weekly newspapers, the Chickamauga Journal and the Lafayette Gazette. (1980)

Randall Williams is an Alabama native, a journalist and former editor of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s newsletter. He is now on the staff of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1978)