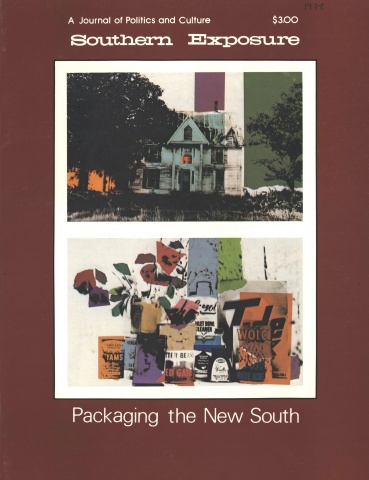

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 6 No. 1, "Packaging the New South." Find more from that issue here.

In South Carolina, “political observers” agree that Democratic gubernatorial candidate and self-proclaimed populist Tom Turnipseed is crazy, or cunning, or both. In the weeks following his Halloween campaign announcement, staged before power company offices in the state’s six largest cities, a traditionally restrained press has freely quoted unidentified politicians who describe Turnipseed as “an inspired madman,” “dangerous” and “demagogic.”

“Turnipseed is a latter-day Huey Long,” one Republican declared in a remark widely reprinted in the state’s dailies. “He’s crazy as a damn bedbug, but crazy in a smart way.”

Many progressives say they doubt Turnipseed’s sincerity, while the rock-hard conservative political establishment bleats warnings about the chaos sure to follow his inauguration. Potential supporters attracted by Turnipseed’s talk of fundamental governmental reform are put off by his rhetorical style, and his emotional stability is a frequent topic over cocktails.

Black leaders are ambivalent about the former Wallace aide and segregated academy organizer: “It would be a national disgrace and embarrassment for a former Wallace segregationist to come from Alabama and be elected Governor of South Carolina by blacks,” the senior member of the black legislative caucus told a reporter. But Isaac Williams, state field representative for the NAACP, demurred: “No one is capable of examining a man’s heart, so you have to look at his actions. We have been able to get Tom’s support on many issues of interest to blacks.... I think people aren’t discrediting Tom’s new convictions.”

And no one is seriously questioning the viability of Turnipseed’s convictions either. Political polls indicate he is presently better known and more respected among voters than any of the other candidates now being mentioned as contenders in the June, 1978, Democratic primary. Supporters believe, and detractors fear, Turnipseed may be able to organize the most broadly-based political coalition in state history, a coalition of blacks, labor, and middle-class suburbanites often dreamed of by Southern politicians. “He has a certain low-class charisma,” a political consultant grudgingly admits. And a veteran political writer concedes that “he may be crazy, but he’s right on the issues. And he’s the only candidate in the race right now who’s speaking out on them. He could win.”

In the context of his rise to prominence, Turnipseed is both a phenomenon and an enigma. Born in Mobile in 1936, he says he was educated in the “forget, hell” school of Southern sociology. “I remember during World War II down in Mobile, we had some Northern people move in behind us. I don’t know where we got it from, but it was like we were supposed to fight them. We were taught in the public schools some real strong biased-type things. We were taught that black people were not really ‘people’ people. It was the worst kind of insulation and isolation.”

Turnipseed was also exposed to Alabama’s populist tradition, and he says he developed a general resentment toward arbitrary power and privilege at an early age. His- father was an entymologist; when Turnipseed was ten, the family moved to Virginia where his father took a job developing oil-based insecticides for Shell Oil Company. “We lived there about two years and then all of a sudden Shell created the Shell Chemical Company, some big corporate move, you know, and all of my daddy’s colleagues were told, ‘You don’t have a job anymore.’ And here he is with three young kids, up in Virginia, an Alabama boy without a job. My father wasn’t a very articulate man, just very good at his research. I never will forget how disillusioned he was with the corporation and the idea that the bottom line is everything.”

Turnipseed’s father found a job with North Carolina State University helping Wilkes County, NC, farmers develop a commercial apple crop. At age sixteen, Turnipseed experienced the first of three emotional breakdowns and was hospitalized for three weeks for treatment of mental depression. (Details of his psychiatric treatment were released recently after opponents leaked the information to the press.) “I just got depressed,” he says. “I was president of my class in high school and playing football and doing everything, and then all of a sudden I started withdrawing. It was a situation of not being able to cope with society as it was.”

Turnipseed played football on scholarship for two years at a North Carolina junior college, then joined the military. Two years later, he enrolled as an undergraduate in history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 1958 and again in 1959, he was hospitalized for depression. “Always in late winter,” he recalls. “It was a terrible experience, but I think I’m stronger today because of it. I found out what I have to do to be happy is to become totally involved in society and absolutely totally involved in helping people.”

In the early ’60s, Turnipseed set out to help white Southerners. He finished law school at Chapel Hill and moved to Barnwell, SC, where he accepted a post as director of the struggling South Carolina Independent Schools Association, a loose-knit coalition of segregated private schools organized in anticipation of courtordered desegregation. “I just felt like it was another example of the South being set upon,” he explained recently. “I was a racist, no doubt about that. And I’m sorry for it. I felt instinctively that the South was being done wrong, but I didn’t really understand the reason. Now I understand and totally believe that the biggest problem we had was being an economic colony. And the thing that has helped perpetuate it has been the racial thing — keeping people divided on race, teaching white people to be poor and proud and hate black people.”

Turnipseed left South Carolina in 1967 and joined the Wallace presidential campaign. “I was attracted to his populism. He was a great deal more of a populist than a lot of people realize, but it was exclusionary to black people to a large extent and that was totally wrong.” Turnipseed served as Wallace’s national campaign director in 1968 and was instrumental in organizing the petition drives that helped place Wallace on the presidential ballot in fifty states. After the defeat, Turnipseed stayed on to organize Wallace’s successful bid for governor and to lay groundwork for the 1972 presidential race.

He left Wallace in 1971 for reasons that remain cloudy. Turnipseed says he was turned off by the political intriguers who surrounded the governor. Some accounts say Turnipseed was fired after he told Parade magazine he would “make Cornelia the Jackie Kennedy of the rednecks,” but Wallace has always insisted they parted on good terms.

Shortly after his return to South Carolina, Turnipseed organized the South Carolina Taxpayers Association and became its first and only executive director. In press releases he described the group as the foundation of a grassroots movement to return control of government to taxpayers. In the beginning a strong conservative influence was apparent within the group; and Turnipseed continued to be attracted to Wallace. After the Maryland assassination attempt and Wallace’s decision to withdraw from the presidential race, Turnipseed tried to organize a draft-Wallace movement in South Carolina.

The Taxpayers Association served as Turnipseed’s first forum for attacks on the political and economic establishment, and his first assault was on the South Carolina Public Service Commission (PSC). The commissioners, Turnipseed said, were dominated by a small group of senior state senators who controlled appointments to the PSC and who were themselves influenced by large retainer fees from utilities. The payment of retainers to legislators by regulated utilities has since become an integral part of Turnipseed’s rhetoric in three campaigns for public office.

Turnipseed says the formation of the Taxpayers Association marked the turning point in his attitude toward blacks. “I'd never really known any black people. When I got to know them through my work with the Taxpayers, I just said, my God, what have we done? 1 started thinking how it would be to be black. To endure what they’ve endured. I began to realize that blacks and whites were going to have to get together to change things.”

Turnipseed began to articulate what has become the underlying theme in all of his battles with the power structure. The South, he said, has been under the control of outside economic forces, epitomized by the New York financial structure headed by David Rockefeller. These forces control the flow of money and use this power to exploit the South, to keep wages low, to keep unions out and to encourage the divisiveness among poor blacks and whites that serves to maintain a cheap labor market. At rate hike hearings, Turnipseed closely questioned power company executives and was able to document a series of financial ties between Northern banks and state power companies. He charged that rate hike requests were a direct result of the banks' conspiracy to reap excessive profits from the Southern colony.

The state press generally evidenced a great deal of suspicion about Turnipseed’s change of heart on the race issue, and columnists claimed the Taxpayers Association was little more than a hollow shell organized by Turnipseed to further his own political ambitions. In the spring of 1972, Turnipseed made a well-received speech before the state NAACP in which he pled for black-white unity. The remarks by a former Wallace operative attracted national media attention; Turnipseed was interviewed on the CBS morning news, and Newsweek mentioned him as a politician worth watching. Turnipseed’s credibility was further enhanced when a prominent black Columbia attorney became the Association’s legal counsel and instituted a suit challenging the constitutionality of a state law that allowed utilities to collect rate increases under bond pending approval from the PSC.

Turnipseed claimed in the summer of 1973 that the Association had 4,000 dues-paying members and predicted that a fall membership drive would produce 200,000 new members “who are tired of this state being at the bottom of everything that matters.” The membership drive never materialized; in November, the Association’s staff resigned amidst charges Turnipseed was interested only in seeking public office. Turnipseed denied the charges, but a few months later, the Association was defunct and Turnipseed announced he would oppose state attorney general Dan McLeod in the July Democratic primary. Turnipseed relied on volunteers to run his campaign while he intervened in new rate hike hearings before the PSC. When he began to gain in the polls, McLeod’s supporters panicked and conducted a well-financed campaign in the black community playing up Turnipseed’s segregationist background. Turnipseed lost, but the margin was small enough to force a reconsideration of the claim that Turnipseed was a demagogue without a following.

Turnipseed’s political fortunes improved in 1976. He ran as a Democrat in one of the state’s few predominantly Republican senatorial districts and defeated his Democrat-turned-Republican opponent by 17,000 votes. During the campaign Turnipseed used tabloids and television spots to attack his opponent for accepting retainer fees from a state-regulated railroad, and he promised to speak out on the senate floor for fundamental reform in state government. Turnipseed told reporters after the election that “the people want leadership and that’s what they’re going to get. Every time a scalawag is paid off, I’m going to expose it.”

The South Carolina Senate is an all-white, all-male body steeped in tradition, and while debates often become heated, gentlemanly conduct is the first rule. Turnipseed was quick to show his disdain for the aristocratic heritage. His open-collared shirts and casual attire were in marked contrast to the three-piece suits and robes of office worn by other senators. His maiden speech was a direct attack on the senate leadership. He cited a nationwide study that found the state general assembly to be fiftieth in functionality, a situation he attributed to a state constitution that places all power in the legislative branch, and a seniority system that allows “a small group of old men” to control government. Turnipseed joined several freshman senators in an attempt to revise senate rules to provide for a more equitable distribution of committee assignments. When the effort failed, Turnipseed lashed out at the senate’s two most senior members, charging them with conflicts of interest. Senate finance chairman Rembert Dennis, whose law firm received more than $200,000 in utility retainer and legal fees over a ten-year period, had been a favorite Turnipseed target for years. On the senate floor, Turnipseed described the fees as little more than bribery. Dennis responded by telling reporters Turnipseed had embezzled funds from the Wallace campaign and was “a fugitive from justice.” When Turnipseed threatened to sue, Dennis admitted he could not back up the charges and made a public apology.

The bills introduced by Turnipseed during his first senate session are consistent with the themes he has voiced over the last five years. In general, they attempt to reduce conflicts of interest in the general assembly, to reform utility rate structures and regulation, and to provide for a more equitable dis- tribution of power. However, none of Turnipseed’s bills were reported out of committee last session, resulting in criticism that his abrasive manner and refusal to work “within the system” have made him ineffective as a senator. Turnipseed disagrees and points to a growing sentiment in the general assembly to alter the selection of PSC commissioners as evidence that his style has been effective with voters. “Besides,” he says “I’m not here to ‘work’ with the legislature; I’m here to change the legislature.”

“Turnipseed Has Appeal, But Can He Govern?” the state’s largest daily newspaper asked a few days after he announced his candidacy for governor. The columnist questioned Senator Turnipseed’s “mercurial temperament and slashing style,” yet still admitted, “He might be able to put together a rare combination of voters: retirees, working-class whites, blacks and liberals. He must be considered a serious contender.”

“I don’t think voters generally perceive him as demagogic or unbalanced,” another state political analyst says. “They seem to be attracted to what they see as righteous indignation. I think voters for the most part feel powerless, and they’re ready to respond to someone who’s telling them they don’t have to be powerless.”

Some observers think Turnipseed can lead the ticket in a three- or four-way primary if he can convince black voters his racism has been exorcized. He appears to be making progress. Last spring he joined black leaders in an unsuccessful attempt to block passage of a new capital punishment law. On the senate floor, he has frequently criticized state agencies for failure to place more blacks in executive positions, and he has appealed to the white business community to “recognize our collective guilt” and support affirmative action programs.

Turnipseed’s willingness to speak out in favor of collective bargaining for public employees and on other issues of concern to organized labor has earned him the support of state labor council president, Jim Adler, and is expected to produce contributions from national labor organizations. His relationship with former Wallace supporters is unclear; some have accused him of “selling out to the NAACP,” but others are volunteering to work in his campaign — evidence, Turnipseed says, that the time is right for a black-white political coalition.

Turnipseed estimates he will spend $150,000 in his campaign — considerably less than the $700,000 spent by reform candidate Charles “Pug” Ravenel in his aborted 1974 race. He says fundraisers are concentrating on small contributions, sales of turniprelated novelties, and “meet the next governor” cocktail parties. Professional political consultants say Turnipseed’s $150,000 won’t be enough, but he believes he can cut costs by severely limiting advertising. “I’m not going to run a traditional campaign. I plan to spend most of my time in the senate working on legislation and fighting for the people. I’d rather have thirty seconds on the news because I’m out doing something for the people.”

Turnipseed will probably face three opponents in the June, 1978,primary — Lt. Governor Brantley Harvey, former state senator Richard Riley, and former congressman Bryan Dorn. All three are moderates and long-time members of the state’s Democratic leadership. Harvey, who has most of the traditional money behind him and is supported by many older black leaders, is considered by some to be the frontrunner at this point, with Turnipseed close behind. Harvey’s Beaufort law firm has received retainers from a regulated utility and some of his supporters fear Turnipseed will be able to dump rising energy costs in Harvey’s lap. “We’re praying for a mild winter,” one says.

Leaders of the struggling state Republican party would like to see Turnipseed emerge as the Democratic primary victor. In their scenario, Democrats who fear Turnipseed will then join with Republicans to defeat him in November. Turnipseed believes he will receive a majority of votes on the first ballot and avoid a runoff, but few observers agree. “Unless he does something really outrageous, I think he’ll make the runoff,” one political consultant says. “If he does, you can bet his opponents will try to combine forces. I mean, let’s face it; he’s a threat to their whole way of life. There’ll be an all-out effort to stop him.”

Tags

John Norton

Formerly editor of OSCEOLA, a weekly newspaper in Columbia, SC, John Norton is now a free-lance writer in that city. (1978)