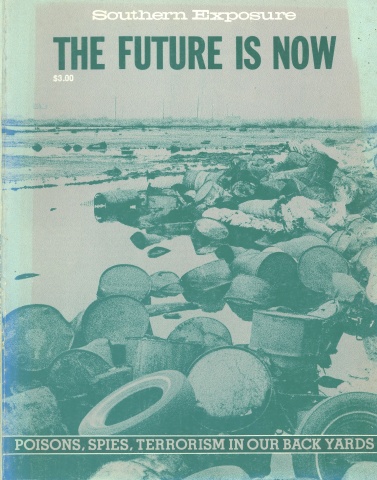

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 3, "The Future is Now: Poisons, Spies, Terrorism in Our Back Yard." Find more from that issue here.

Nell Grantham has lived all her life in Hardeman County, Tennessee. She, her parents, her brothers and sisters and their families make up most of the residents of the Toone-Teague Road. Just down the road from their houses sits their most important neighbor, however — a 242-acre chemical dump site owned by the Velsicol Chemical Company.

In 1977 Nell and her family began to wonder about the quality of water found in their wells. After months of questions, they finally learned the truth: Velsicol’s dump had leaked deadly chemicals into their water supply. Since then, these rural people have battled against the giant corporation to seek compensation for the injuries caused by Velsicol’s improper disposal practices.

The troubles she’s had over the past few years might have overwhelmed a lot of people. But Nell Grantham has kept her spirit and fought on with amazing vigor. She is now the chairperson of TEACH — Tennesseeans Against Chemical Hazards — a statewide group of dumping victims and landfill opponents banded together to seek sane waste management policies and to protect citizens from the sort of atrocity visited upon Hardeman County.

Nell recently took the time to sit down and relate her ordeal to Southern Exposure and also outline the exciting efforts now being undertaken by TEACH.

In 1964 the Velsicol Chemical Company bought a 242-acre farm in Hardeman County. Or someone did, and it got mysteriously turned over to Velsicol. We looked up the deeds, and it changed hands six times in two months before they finally got the deed to the thing. The health department came out when they were permitting the site. They told Daddy that there was no way the stuff would get out. At that time there were only three families that lived within four miles of the place.

Velsicol dumped 300,000 55-gallon drums of unknown chemicals at the site. The way they buried it was they took a dozer and dug 15-foot trenches and had a dump truck back up and dump it. Some of the barrels were not capped; others burst open when they dumped them in the pit. They just covered them over with about three feet of soil and ran a bulldozer over the top of them.

You could follow the trucks from Memphis and smell the chemicals. We had no vegetation growing on the sides of the road whatsoever where they were hauling that stuff in here, cause it killed it.

They had a fire up on the dump one time when they were still using the site. Thought the world had blowed up up there. That was around ’68, ’69. I think it burned the dozer up.

In 1967, a USGS [U.S. Geological Survey] report showed that the chemicals were leaking out, five years after they started dumping. We found another document that in 1967 the state of Tennessee had a public hearing that no one knew about. In 1967 I was 12 years old; that’s how much good it did me to know about that meeting. No one was there except Velsicol and the state. George Wallace, the environmentalist for Hardeman County working for the state department of public health, was there.

We got a copy of what was said in the meeting. At one point George Wallace stated that the chemicals were getting into the residents’ water supplies, that he couldn’t go out there and tell the people this cause he’d have a mass panic on his hands. In 1967, from Highway 100 to the Teague Road — that’s about four miles — there was only three houses. That’s the type of mass panic he would have had.

Finally, Eugene Fowinkle, commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Public Health, closed Velsicol down here in 1972. He was at the public hearing in 1967 and knew about the leaking, but he didn’t close the dump down for five years.

Velsicol Chemical Company was thrown out of Shelby County in 1964 because they were dumping in the Hollywood Dump. They dumped in Hardeman County until ’72, when Fowinkle closed them here, then they went right into other parts of Tennessee to dump — and one of those places is Bumpass Cove, Tennessee. I know they have dumped in South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama — all through there.

In November of ’77 citizens in our area began to notice a foul odor, a smell and taste to our drinking water. We all had private wells, anywhere from 90 to 200 feet deep. Our water had gotten so bad that you could set a glass of water on the table overnight and it would congeal — like a jelly-type thing. There was oil film on the water when you’d run it; when you’d run a dishwasher it’d leave a powdered film on the dishes.

Everyone out here is family. I have two brothers and two sisters. We all married, but we never left home. We brought em back with us, and we built next door to Momma and Daddy. Daddy — Steve Sterling — is a little bitty short guy, couldn’t weigh but about 120 pounds, but he seems to rule with an iron hand, and always has. If you can convince my dad, you can convince anybody in the world.

Everybody takes their complaints to Daddy. Everyone always has. We were all complaining, “Daddy, there’s something in our water.” Or: “Daddy, there’s these funny little white things floating around in our bathtub. Can’t you smell that stuff in the water?”

“Oh, all you kids are crazy. You don’t know anything.”

Anyway, Daddy got sick; he had a real bad kidney infection. Momma took him to the doctor, and the doctor put him on medicine and told him he had to drink 12 glasses of water a day cause of the medicine he was taking. My Momma’s pretty stubborn, so she decided while he was home he would drink his 12 glasses of water a day. She gave it to him for about three days; he ended up in the hospital, and we thought he was gonna die. Because of the water. It was never proven that it was because of the water. But it didn’t happen until Momma was making him drink the water.

After Daddy got out of the hospital he said he wasn’t gonna drink any more of the damn water, and we started hauling it in. Everybody started hauling. So we all got together and got to talking about it and that’s when we went to George Wallace. As my Daddy said then, “George Wallace works for our health department; we pay these people; we voted them in office; they’re going to protect us.” We wanted our water checked, but the only thing he tested for was bacteria. He never said a thing about the USGS report — said there wasn’t anything in our water.

So we kept asking the local health department what was wrong. They kept saying they couldn’t find anything — they tested two or three times. They finally told us we would have to see the [state] water quality division in Jackson. We took a water sample to these people; they told us that they couldn’t test it because they didn’t take the samples themselves. We started in November with our local health department; in March we finally got water quality to come out and take a test — March of 1978.

They came back and told us that we might have a problem. After two or three more tests, they told us that we had chemicals in our water — what type they didn’t know. But they kept testing and they came up with a list of 12. I think five of these were known carcinogenics at that time — benzene, chlordane, heptachlor, endrin, dioxin, those are the major ones I remember. That was April that they finally told us that.

They kept on testing and finally got the EPA down. They sent a sample to the EPA and we waited about six weeks. We hadn’t gone to the media with any of this cause the health department and the state had asked us to keep it quiet until they found out what was going on. After we waited about six or eight weeks, we called the EPA in Atlanta. We were told that we were not a public water system and that since we didn’t have 25 or more people on one well we would have to wait our turn; that could be six months to a year.

We called our senator, Jim Sasser, and told him what was going on and he called the EPA and got our water tested. At that time they found 21 chemicals and 11 known carcinogenics. They came out and they told us — they never told us to stop drinking our water, they just advised us that we shouldn’t use it to cook or drink, that we could only use it to take baths in, or for household cleaning, and to take cold showers no longer than five minutes at a time. So we did this for three or four months. Then they came back and told us that the percent of chemicals in our water had risen real high and they told us not to use our water, other than just for bathroom facilities.

We finally went to the media cause we were really getting the runaround. In October of ’78, after we got some media attention for our problems, EPA came out and advised us not to use our water at all. They told us we couldn’t have any gardens because of the chemicals getting into the food chain. No stock animals for food such as beef or pork or poultry — anything like that. A neighbor of ours had a hog that we sent to a lab in Nashville; it was highly contaminated. They told us do not risk eating them at all. We also have a lot of natural springs around here that come under this dump and pick up the chemicals.

At the end of October, my brother Woodrow and his wife Christine went to congressional hearings in Washington. They got into the hearing and found out that we had the most dangerous chemical of all, which was carbon tetrachloride, running at about 13,000 parts per billion in our drinking water, and we were drinking it. If you look up carbon tetrachloride, you’ll find that a teaspoonful of it is lethal. We don’t know how much we got.

So they finally came out and told us to cut our wells off — not to use them at all. It was like camping in your home. Families would carpool together, and each family one night a week would take all the kids, or whoever wanted to go, and go to a public shower in Chickasaw State Park, which is about 15 miles from our home, to give our kids a bath at night. You’d go visit a neighbor and you’d say, “Can I take a bath?” or “Can I give my kids a bath before I go home?” You’d go to a public laundromat to wash your clothes when you’d bought and paid for a washer and dryer to use in your own home. All this was at our own expense.

The National Guard was bringing us in the water tankers that they use on maneuvers; they were bringing us 500 gallons of water twice a week, and this was for a community of 32 people, including children. We were totally cut off for about six months — all the water we used we hauled. They even told us that our kids shouldn’t be laying on the carpet watching TV if we’d steam-cleaned the carpets. The stuff was in our carpets, in our paneling — it was in everything. All of our plastic dishes, tupperware — anything that had plastic in it — these chemicals would absorb into them and when they were used we’d get another dose of the chemicals.

Once we got the media to cover our story, Velsicol finally said, yes, maybe it was their chemicals. They never said that it was their chemicals; they said that it probably is. I guess you would say as their Good Samaritan act, they’re doing all this stuff. They started running water out of Jackson, Tennessee. We got water in a gasoline tanker; the water was rusty, but it was water.

Then they came in and put in a temporary tank — 10,000 gallons, I believe — and they started running water to some of the homes. They had to come into our homes and replace the plastic PVC pipes, our hot water heater, our faucets. We were granted some money from HUD and the Farmers Home Administration to put in a main water line from the city of Toone. They granted us $250,000 together to put in the water, and the city of Toone had to come up with $30,000. The city of Toone turned down the proposal. We asked if we could not be incorporated and build our own water tower. Then the city of Toone wanted us to have the water.

It wasn’t costing me $5 a month to run my own well, but now I have to pay a minimum of $10 a month for water and have since 1979, and no one has offered to pay it back. Velsicol said they would pay for all the fixtures we had to have changed like our hot water heaters, dishwashers, washers and dryers — they said we could not use these anymore because of the plastic fittings in them because the chemicals would stick to them. They did replace my hot water heater, but I’m still having to use my washer and dryer and dishwasher because I couldn’t afford to buy another one and can’t afford to go to a laundromat each week. So I’m still using those.

Shortly after that, Velsicol started work on putting a cap on top of the dump site. They finished late last fall. They put in three feet of clay, loam and topsoil, and they seeded it. The cap is now washing away; there’s some ravines up there that’s knee-deep to waist-deep on me. Velsicol is now filling in the holes and re-seeding. When the seeds came up this spring, they came up around the pits; over the pit areas the seeds did not grow at all. It looks beautiful from the road cause all you can see is this tall green grass; it looks like a golf course. But you get out on it and there’s not very much grass on the pits. They tell us that it’s expected it’ll do this, and it’ll take two or three years to get the cap settled in — that’s a bunch of bull.

They also put in some monitors at the dump when they put the cap on. What it does is measure the rainfall that comes through the cap. The type of clay they use should turn the rainwater back so it doesn’t penetrate and pick up the chemicals and get into the water table. Supposedly. They went in to see how much water had gone through their cap in six months’ time. When they pulled the tops off their monitors they found that the monitors were full of water and also contained nine chemicals; they’re trying to figure out how they got in there.

They say the stuff is still vaporizing out; when it rains here you still get the foul odor and the smell from the dump, your eyes burn, and what have you. There are 1,000 acres in Hardeman County that are contaminated. They have even lowered our taxes because we live in the contaminated area.

I moved away from Hardeman County for six months. I moved to Chester County cause my father-in-law had had a stroke and we were taking care of him. When I came back, I noticed there was a smell and a taste to our water. Everybody else said I was nuts, but to me it seemed they had gotten used to it and I hadn’t. So I started asking around and got some water testing done by Dr. David Wilson. He found some PVCs. He’s not sure it comes from the plastic used in our water lines. Velsicol does make a chemical that is similar to PVCs; we’re waiting to find out if we have chemicals or we do not. One reason that we suspect Velsicol is that they put in our water tank on the dump site and our water lines come directly across the land Velsicol owns close to the pit.

There are no men who have lived in this area for 20 years that are over 60 years old. The last three that died all worked for the chemical company. My uncle, George Wilson, worked on the dump; he just did little odds and ends. He died last September. Roy Wilson, another uncle, died in January; he ran the bulldozer there. Clyde Thomas died a few months ago; he bought the trucking firm that hauled the stuff in. Leroy Agee owned it before that; he is in real bad health. He looks terrible; he has emphysema, cancer, heart damage and I don’t know what-all. Another fellow who hauled the chemicals is on a dialysis machine three times a week. A first cousin of mine has had 24 skin cancers removed. I’m not saying that working up there caused it, but it looks sorta suspicious.

The long-term health effects are what I worry about, plus continued exposure to chemicals vaporizing off the dump, or what might be in our water. Who knows? In 20 years my kids may have cancer. I may never have grandchildren. I may not even live to see my kids grown. That’s something we don’t know. That’s something no one knows. But when you’ve been drinking contaminated water with chemicals that you know can cause cancer, that makes it look worse. My kids are my biggest concern. What kind of life are they gonna have?

There’s not been a child born in this area in the last four years. The last child was born without an abdominal wall. He was rushed to a children’s hospital and spent three months there. They did surgery three times; since then he’s had surgery on both eyes, been back in the hospital several times — they didn’t think he’d make it for a while.

Out of my Momma’s 11 grandchildren, nine wear glasses. Hearing problems, vision problems — their teeth look awful. Every kid on this road has had extensive dental work. My two kids had $1,500 worth of dental work done on baby teeth; the dentist said he didn’t know what was causing it, but that if he didn’t fix them it would deform their permanent teeth. My younger daughter, Penny, lost three teeth last week. I don’t know if she’s trying to raise money or what. Both my children complain of muscle cramps, fatigue really. They refuse to drink the water at school cause they say it has a taste. I think everybody through here has arthritis. Nerve damage, numbness of the limbs. You get up and you can’t walk; your legs don’t work. Skin rashes that you don’t know what causes it.

We left for a weekend and my husband’s skin rash cleared up; he comes home and takes a shower and he breaks out again. You just wonder. After all we’ve been through, there may not be anything wrong with my water now, but I’d like to know for sure. Maybe it’s in my head, but I wish somebody’d prove it. It’s like a nightmare you didn’t wake up from. You have all these people telling you, you feel like everybody’s patting you on the head like you’re some little child, saying, “Just calm down, calm down, everything’s gonna be all right, I’m gonna handle it.” And nobody does anything. So I’ll do it myself.

If I have the money I will move out. Right now I can’t afford to, but I’ll get my kids out of it one way or another. And I’ll certainly check out the area before I move anywhere, see if they got anything laying around.

There are about 80 people right now in a class action suit against the Velsicol Chemical Company for the sum of two-and-a-half billion dollars. We go to federal court October 21 at 9:30 a.m. We have seven families that have settled. The lowest amount a guy settled for was about $12,000, and I think the one that got the most got about $50,000. Everybody I talk to — the different lawyers and all — say we have a perfect chance; they don’t see why we can’t win it. There is no way these citizens down here could afford to hire a lawyer. So the lawyers will get a third of the settlement — but only if they win. I may not get but 10 cents, but they’ll know I’ve been there — the state of Tennessee and Velsicol, too.

In the spring of '80 I went to a meeting with some people at the Highlander Center outside Knoxville, a workshop on toxic chemicals. I didn’t know what I was going for, but I am a licensed practical nurse and it’s something I thought I might learn from, so I went to their meeting. While I was there, I met people from five other counties that had the same problem I did — chemicals were in their drinking water, or they were having a landfill put in, or they had a landfill and the state of Tennessee was doing nothing but patting them on the head and telling them, “Don’t worry about it.”

The biggest thing I found out was that Eugene Fowinkle had gone into Bumpass Cove, Tennessee, and told these people, “Why, don’t worry about your little ole dump; you ought to be with the people in Hardeman County.” He told the people in Hardeman County that Bumpass Cove was worse; he was telling us two different stories.

When he came back down the next time and told me that, all I did was hand him a press release from a paper in east Tennessee where he stated that the dump in Hardeman County was worse than Bumpass Cove; then here he was telling me that Bumpass Cove was worse than me. Uh-uh. He backed up at that.

That’s how TEACH — Tennesseeans Against Chemical Hazards — came about. The six counties that were at that workshop got together and decided the citizens of Tennessee would band together and fight the state as one, not one little group at a time. We voted to become a coalition and started working on it in the spring of 1980.

So far we have shown films on chemical hazards in the different counties. We’ve met with people that were willing to help educate us, like toxicologists, and have worked with organizations like TNCOSH [Tennessee Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health], the Highlander Center and the Tennessee Toxics Program. They’re showing us what the state’s supposed to be doing. We have also gotten citizens in other communities together. We have groups like the Cypress Health and Safety Committee, Concerned Citizens of Frayser; Hardeman, Hickman, Madison, Davidson, Sullivan and other counties now belong. We have the POW, that’s People of Woodstock; they’re going under the name of Prisoners of Hazardous Waste (they just leave the “H” out). It’s really a statewide organization, from one end to the other.

Our biggest success was when we had a group from Hickman County come in and ask what TEACH was about. We told them we were a group to educate other citizens, show them how to organize, what types of things to look for if they had a dump or were about to get a new one. With our help, the Hickman County folks went back home with about six weeks’ notice before there was a public hearing for a landfill to be put in their county. These people, when the state got there to hold their little hearing, had 1,000 citizens banded together to fight that dump. The state backed out; it was not approved. HALT — that’s Hickmans Against Lethal Trash — then went into the next county and started to organize there, because the company proposed to move over to that county; so they’re still fighting the landfill.

Another victory we had was in Sullivan County. Sullivan County has a municipal landfill. The owners wanted to put in a “special waste” landfill for highly toxic chemicals. The special waste permit was denied to the owners of the landfill because the citizens got an independent USGS report that proved the land was unfit for a special landfill. When the state had the hearing, TEACH members from all across the state of Tennessee were there to support the Sullivan County group. After they all testified, the permit was turned down.

We heard that some people in Smyrna were going to court against a company. We hadn’t even gotten in touch with these people, yet we were there when they had their court date and we testified for them. And they won against the landfill that had polluted their wells.

Now the citizens of Tennessee are keeping their eye on what the Tennessee Departments of Public Health, Solid Waste Management and Water Quality and all are doing. We’re asking questions and we’re wanting answers. And we’re looking for our own answers. We’ve looked into alternatives for landfills. We’re not in the position now — financially and otherwise — to hire lobbyists and all this, but we do ask questions of the state.

The biggest thing we’re doing right now is educating the citizens of Tennessee so they’ll know what’s happening — how to keep records, what to look for, what the state and industry are doing. For instance, we got a copy of a report that Water Quality did on all the rivers. They’re all polluted, but the worst two are the Loosahatchie and the Wolf River in Memphis, and people have been fishing out of these commercially. Fowinkle finally got up and said, yes, they were contaminated and that somebody needed to put up signs telling people not to fish and not to swim in these areas. He said it was up to the Department of Wildlife to do this. We did some checking and found out that it was not the Department of Wildlife, it was the Department of Public Health that was responsible, so we all sent letters and pressured the governor and Fowinkle to put the signs up. The last word I had was that the signs were in the making and that they would be up before long. So it’s small victories, but we’re getting there.

Betsy Blair is working with TEACH through the [Vanderbilt University] Center for Health Services. She’ll be condensing all the information on the different counties that are in TEACH, the problems they’ve had, what’s happened with them — just a brief summary of it. She’s gonna be working on a health survey to profile the health of people in the state of Tennessee. We know that the Appalachian mountain area — Bumpass Cove, Erwin, Washington County and all that — has a lot of cancer and heart attack victims. So what we’re gonna try to do is take the state apart in sections and see what factories and chemical companies are located in those areas, what they make and what health effects might be associated with them. Big job, huh?

Rob and Carol Pearcy and I have gone through a training program to take over the work of our staff person. I hope I know more than what I did, I think I do. Now we’re working on some fundraising for TEACH. All donations are appreciated.

I’m fixing to go to Connecticut, Rhode Island and New York to talk to some people up there, statewide coalitions, people that have the same problems, and see what they’re doing up there. I want to see if I can find anything that’ll help TEACH and just try to make myself more aware of what’s going on. Educate myself, really.

When people I talk to get discouraged, I try to let em know that what is happening in their county is the same thing that happened in Hardeman County. I’ve been there; I know what’s gonna happen. But neither them nor I by myself is gonna stop it. It’s gonna take us all working together, and together we can do it. But by ourselves we can’t.

People are all the time saying to me, “Well, somebody needs to do something.” I look at that person and I say, “Well, what’s wrong with you? You can do it. Get in there and fight. Don’t give up. Together we can do it.”

For more information about TEACH and Tennessee dumping hazards, contact: Nell Grantham, Route 2, Box 192, Meden, TN 38356 (901) 658-5963.

A CHEMICAL GLOSSARY

Arsenic is a metal released during different industrial processes such as coal combustion and pesticide production. It causes lung, skin and liver cancer and birth defects. Exposure symptoms include nausea, vomiting, skin inflammation and muscle weakness.

Benzene results from the production of organic chemicals, pesticides, solvents and paint removers. It is a carcinogen which causes aplastic anemia and leukemia, as well as other blood diseases. Prolonged exposure can cause headaches, dizziness and injury to blood vessel walls.

Cadmium is a metal produced by mining and smelting operations, coal combustion and other industrial operations. It hampers breathing, can damage the lungs and cause cancer of the lung, liver and prostate, as well as cell mutations and birth defects.

Carbon tetrachloride is used as a solvent, as a cleaning and degreasing agent and as a fire extinguisher. A carcinogen, it is highly toxic to the liver and kidneys and causes severe depression of the central nervous system.

Cesium primarily results from nuclear power generation. It concentrates in soft tissue and the genital organs and may cause cancer.

Chlordane and heptachlor are insecticides that cause cancer and affect the central nervous system, eyes, lungs, liver and kidneys. They also can create acute poisoning symptoms: stomach pains, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea and convulsions. Their use was suspended by EPA in 1978.

Chromium is a metal used as a corrosion inhibitor, in chromium plating and in various metals industries. Exposure to chromium compounds can cause ulcerations on hands, arms and feet; chest pains and bronchial inflammation; and perforations in the nasal cartilage. It is suspected of causing lung cancer.

Cobalt is used in steel and paints and also in medical therapy. It irritates the skin and eyes; causes illness when swallowed; and can cause heart stress and thyroid damage.

Dioxin is a side product of 2,4,5-T, a component of Agent Orange. Animal tests and some of the evidence from exposure to humans indicates that dioxin causes both cancer and birth defects.

Endrin is an insecticide that has caused cancer in test animals. It affects the liver and central nervous system, and also causes the acute poisoning symptoms listed for chlordane.

Iodine-131 is primarily a product of nuclear power generation. It accumulates in the thyroid gland and can cause cancer.

Kepone is an insecticide that affects the central nervous system and is toxic to the liver and the testes. Its production was suspended in 1979.

Manganese is used in a variety of industrial processes, including mining and ore processing. It affects the respiratory system and can also cause central nervous system damage such as acute anxiety and hallucinations.

Plutonium-238 and -239 is a fission product of nuclear plants and weapons; it is found in radioactive wastes. It concentrates in the bones, liver and spleen and can cause liver and bone cancer, lung cancer and leukemia.

Polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) are used as fire retardants. They are carcinogenic and mutagenic to test animals and cause symptoms such as headaches, muscle pains and diarrhea.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are used in electrical and transformer fluids and for flameproofing. They are carcinogenic and particularly damaging to the liver and skin. PCBs can cause neuralgia, hearing disturbances and stillbirths.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is used to make hundreds of plastic products ranging from baby bottles to food packaging to cosmetics. It causes birth defects and cancer, psychological disturbances, impaired liver function, central nervous system depression, dizziness, nausea, dulled vision and changes in skeletal joints.

Strontium-90 is a fission product from nuclear power plants and weapons; it is often found in radioactive wastes. It causes bone cancer and leukemia in animals.

Toluene is used in the manufacture of benzene, chemicals, plastics and paint. It causes liver damage; irritates the skin, eyes and upper respiratory tract; and causes weakness, fatigue, confusion and dermatitis.

Tritium is a radioactive form of water primarily resulting from nuclear weapons manufacture and use and the production of luminous dial watches. Its health effects are uncertain at present, but it does get distributed to every cell of the body.

Ytterbium-169 is used as an x-ray source for portable irradiation devices.

The information above is adapted from We Are Tired of Being Guinea Pigs! A Handbook for Citizens on Environmental Health in Appalachia. It is an excellent publication which also contains useful information for people in other parts of the country. It is available for $5.00 from the Highlander Center, Route 3, Box 370, New Market, TN 37820 (615) 933-3443.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.