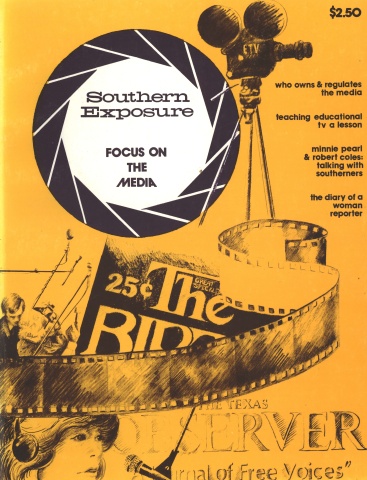

The Texas Observer: "A Journal of Free Voices"

Quinney Howe Jr.

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

To be candid. I suspect the planners of this forum invited me to participate because of their awareness that sometime in that past that now seems so remarkably distant - the era before John Kennedy’s Camelot — I was one of a species that Lyndon Johnson was known to describe, not always with love and affection, as “those Texas Observer boys.” I suspect, in short, that some sort of roman a clef is expected from me, a bit of “inside folklore” about some of the lonely dissidents of the “silent generation” of the Fifties. I will endeavor to oblige, at least in the highly personal and idiosyncratic way that has over the years become characteristic of the Observer itself.

I recommend The Texas Observer - if not invariably to potential subscribers, then certainly to young writers, to students of power in America, and to those aspiring literary types willing to discover the range of their own weaknesses. The Observer is a remarkable training school — intellectually on a par with graduate school and emotionally quite beyond it. Willie Morris, Robert Sherrill, Chandler Davidson, Bill Brammer, among others, all attended the Observer school, variously afflicting their readers with the results, and then moving on to other work with an observably altered perspective. I mean this quite literally. Their writings, before and after their Observer experience, are readily available and reflect rather clearly, I would argue, the extent to which certain lessons were absorbed and made a part of what is self-evidently a post -Observer perspective. But before I can attempt to characterize what we became, I must pause to describe what I think we were, the raw material that the Observer experience reshaped.

Beyond the Cowboy Culture

Growing up in Texas in the 1940s and 1950s, one read a kind of literature that, in retrospect, can be seen to have addressed a question that we, the provincial young, had not quite found a way to ask. We read, first and most importantly to us, William Faulkner. We also discovered the sad cafes of Carson McCullers. We read Lie Down in Darkness by William Styron — and heard a decent, ruined, drink-sodden father tell his son to “be a good Democrat and, if you can, be a good man, too.” We read Southerners.

We also read Norman Mailer, Bernard Malamud, and Saul Bellow —that is to say, we read Jews. They seemed to speak to us with every bit of the power conveyed by the saga of Faulkner’s delta.

And, finally, we read Melville and Henry James and disagreed mightily as to the tolerance we could bestow upon the education of Henry Adams. We read the children of the congregationalists, the transcendentalists, and the abolitionists. The old New Englanders. In their own curious way, they were revolutionaries all.

Unconsciously, perhaps, we were imbibing the fruits of powerful cultural traditions —Southern, Jewish, and patrician Yankee— traditions that dealt with the deepest range of human emotions. But when we turned to our own roots, to the heritage of our own land, here on the Southern frontier, we did not learn very much about hope and despair, striving and tragedy. We found instead a thin, celebratory literature of western triumph. We found hardy frontiersmen, tall in the saddle, riding up the Chisholm Trail, overcoming sundry hazards and, like Charlie Goodnight, carving baronial domains in the plains wilderness. The centerpiece of this gigantic western drama — the cowboy (and his governmental counterpart, the Texas Ranger)-was to be taken seriously. Southwestern writers —the ones who were white and male — tried to make us understand this, by the very way they wrote about their archetypical figure. He was a very special kind of frontiersman, with a Colt revolver rather than Hawthorne’s Long Rifle. We were told that Barbed Wire and Windmills, when coupled with the Colt six-gun and grouped together on the Great Plains, produced an important kind of democratic culture. Walter Webb told us this and, in his own way, so did Frank Dobie.

It was our lot, in the Forties and Fifties, to grow up in Texas and not to believe. If there is any intellectual justification in having Larry McMurtry grouped with The Texas Observer writers as a subject of academic attention, it is in this solitary fact — that we were all approximately the same age and we shared a generalized disbelief in the alleged virtues of the received regional culture, as well as in the larger national ethos that drew so heavily from the mystique of the western frontier.

McMurtry has been discussed by Warren Susman and I will not intrude upon his domain, other than to say that, to me, McMurtry’s early works, like the pages of The Texas Observer of that era, can profitably be read as exercises in the loss of innocence. As literary criticism, I think it is imprudent to venture much beyond this: the “end of innocence” —while rather essential— is not coterminous in time with the beginning of profundity. Indeed, one misses the essence of the youthful probing and disarray of the Fifties (what there was of it), if one fails to focus upon what was clearly, to those of us in Texas at least, the paramount concern: finding a usable past out of the thin shelter of the frontier South.

We had great respect for Walter Webb as a man and as a venturesome historian, but when, in the climate of the McCarthy era, we read Webb’s eulogy to The Texas Rangers, it seemed not only to be a singularly unsatisfactory exercise in racial and cultural aggrandizement, but, much worse, a profoundly innocent book. As for Dobie, we only wished he had as keen an eye for the narrowness of vision of the actors in his western saga as he did for similar defects he found in contemporary American society.

In sum, though we disagreed among ourselves as to the extent of the failure, we found the regional heritage to be thin, romantic, and not to be compared to the intellectual legacy bequeathed to the young of New England, or of the Old South, or to those of the Jewish cultural tradition. These three disparate groups, of course, have long shared a common anxiety about the prospects of man generally, as well as the prospects of man in American democratic society. In contrast, the saga of the cowboy somehow did not stir such creative introspection: it encouraged a generalized Texan and American complacency. Eisenhower in a Stetson: America at mid-century.

The numbing tragedies that suffuse American life, including the monumental tragedy growing out of the American caste system, but including also the structural failures that periodically surface within the American democratic system itself, are thrust upon Observer writers with a sobering power. This has been going on for quite a number of years now and enough evidence is in to provide an interesting perspective both on the Observer itself and on the surrounding culture which its journalists have experienced and attempted to describe.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s — while other young people were reading history texts that proclaimed “the genius of American politics,” the Observer thrust its reporters into the very maw of the on-going political world. The press releases of administrators, the public committee meetings of legislators, the personal techniques of governors, senators, presidential aspirants, and presidents — all the public paraphernalia that contributed to the surface sheen of politics-were part of the experience of a young Observer writer, as it was for other journalists. But the nature of the Austin journal, as pioneered and set in place by its founder and guiding spirit, Ronnie Dugger, thrust his young minions quite beyond the visible epidermis of democratic appearances into a tangled interior of bone and marrow that proved fascinating, if not unfailingly appealing. This interior world of realpolitik is not easily described, though one of its principal features seems beyond dispute: in this nether world, frenzied arteries and errant capillaries pumped the blood of politics —money—into all manner of receptacles largely unknown to the founding fathers. After sustained contact, Observer diagnosticians tended to conclude that the patient, attractive and heralded though he was, seemed in reality quite sick. I think it can be proved, from the pages of the Observer itself, that this discovery was conveyed with some sense of shock and considerable outrage. For most young Observer writers, the end of innocence was not a pleasant moment.

The form of the Observer's literary response to the world of democratic corruption varied in interesting ways. Lyman Jones had a kind of earthy anger that conjured up the image of a trail land whose steers have suddenly and perversely begun to stampede out of control. If Jones did not invariably locate the cause, he had few rivals in cussing the results. Bill Brammer was captured by the transcendent power of the lobbying process itself, one that seemed to him to render reform utterly futile and left the reformers vulnerable to ridicule. Bill turned his deepest attention to the politicians who brokered the demands of lobbyists. He became a student of Lyndon Johnson and, one surmises, an admirer as well.

Willie Morris never ceased to be offended by the gracelessness of it all. Few of the plunderers seemed to him to possess a redeeming style and none seemed to have more than fleeting intuition about the human costs involved in “the game.” Willie attempted to extract humor from the more grotesque examples of corporate regime in Austin, but the laughter often was hollow and, at such times, the underlying despair in Willie became visible. Bob Sherrill married hyperbole to satire and walked through the daily mine fields of his political beat with the fatalistic poise of a combat infantryman. If he was seldom surprised by the periodic explosions of scandal, he rarely lost his capacity for indignation either. He wrote as if his revelations could make a difference, even though he felt they would not.

To the underlying ethos of the Observer, Ronnie Dugger brought an ethical constancy that was impressive to know. He knew the merits of skepticism and the pitfalls of cynicism and rather effortlessly and consistently distinguished the two. He assumed all public men were honorable, and based his personal relations on that premise, meanwhile reporting his disappointments with unrelenting detail. Though the sheer buffeting of experience on his journey wore out any number of energetic young writers in the prime of youthful resiliency, Dugger has continued year after year to expose himself to the fissures and crevasses that define so much of the democratic landscape in Austin. He is now a middle-aged I. F. Stone, which makes him a mere apprentice in that rather lonely and splendid craft of personal journalism that Stone best epitomizes. I, for one, anticipate that some 20 or 30 years hence, Dugger, in full iconoclastic maturity, might well resemble his illustrious and uniquely useful predecessor.

However, Dugger cannot be characterized quite so quickly. I don’t think one can make much sense out of The Texas Observer, or its writers, without pausing first to mark the defining impact on both of the founding editor. The circumstances of those early years, when Dugger toiled away in isolation as editor, writer, copyreader, and layout man, shaped the Observer in fundamental ways and imparted the special independent character that has since identified it.

The Observer dates from 1954 — those grim days that marked the foreboding twilight of the McCarthy era. In Texas, Governor Shivers, as spokesman of what Dugger would soon label the “Tory Democrats" had led most of the official Democratic hierarchy into public support of the 1952 Republican presidential candidate, General Eisenhower. This event disrupted the Texas Democratic Party and precipitated a tumultuous struggle for the soul of the party that matched Shivers against a Populistically-inclined judge who subsequently became rather well-known in these parts —Ralph Yarborough.

Big Beginnings

That 1954 campaign had a transforming emotional impact on Texas politics that visibly persists to this day. In terms of money spent, chicanery, corruption, demagoguery, and rhetorical violence, it was the nearest thing to a class struggle that the state has endured since Populism and Reconstruction. The legends it inspired became part of the received culture of each new Observer writer through the Fifties and Sixties. The central one concerned the filming and distribution by the Shivers forces of what came to be known as the Port Arthur Story. It merits a brief review here for it was the centerpiece of a maturing partisanship that The Texas Observer, under Dugger, both heightened and —in telling ways - ignored.

It seems that during the 1954 campaign a strike of retail clerks was in progress in the little southeast Texas city of Port Arthur. The crew arose before dawn in order to be in place in downtown Port Arthur literally at the first sign of light. The purpose was to photograph a silent, faceless city, one deadened by the nefarious agitators of the labor movement. According to the legend, passing bread trucks and other early morning intruders forced the cameramen to stay on the job for three or four consecutive mornings before they were able to amass the required footage of empty streets. At the climax of the Yarborough-Shivers campaign, the television screens across the state issued forth a dramatic documentary that began in utter silence, with long seconds of panoramic sweeps of what seemed to be a deserted city. Then, after a minute or so of eerie silence, a narrator suddenly intoned: “This is Port Arthur, Texas. This is what happens when the CIO comes to a Texas city.” The 30-minute documentary that followed had other novel elements, such as footage of pickets, notably black pickets, bedeviling the serenity of little Port Arthur. The “Port Arthur Story” became the central campaign document of 1954 and was shown repeatedly in prime time throughout the state.

The extremely narrow Shivers victory that concluded that wild summer of campaigning set in motion the dynamics that created The Texas Observer. In a post-mortem illuminated with outrage and indignation, the “Loyal Democrats” of Ralph Yarborough decided the political process had been purchased by the Tories, who had “manipulated the media, deceived the voters, and sabotaged” the democratic idea. A number of them, including a group of prominent Democratic women, got together and decided to underwrite a newspaper organ that would spread “the truth.”

Late in 1954, their dream became a reality, though not precisely the way they intended. They selected as editor a young man newly home from Oxford. His return route to his native hearth in Texas had included a brief sojourn in Washington that had apparently stirred some latent reform instincts. In any case, Mr. Dugger assured the underwriters that though he was a “good Democrat” (in the parlance of the times), he really didn't believe in newspapers as “organs.” He promised instead what he called “a journal of free voices.”

Within a month, young Dugger had the loyal Democrats of Texas in an uproar. The first controversy developed out of the subtitle Dugger selected for his paper: “An Independent Liberal Weekly.” In the high tide of the McCarthy-Shivers era, the word “liberal” did not have galvanizing appeal to Southern voters. Old partisans of the Jefferson-Jackson-Franklin Roosevelt tradition in Texas identified themselves as “loyal Democrats” or as “good Democrats.” never as "liberals.” The latter word identified people who were too preoccupied with the civil rights of black Southerners, and Dugger’s quixotic adoption of the term did not augur well for the propagandizing techniques of the new “organ.” The issue was scarcely a merely theoretical one. The subscription list of the new Observer was largely composed of some 2,000 white East Texans who had earlier subscribed to a paper known as the East Texas Democrat. These subscribers were thought to be particularly sensitive to matters of race. Dugger seemed to be flirting rather dangerously with the very foundations of the shaky new journalistic enterprise.

Dugger’s response was characteristic—and defined for all time that the operative portion of the Observer's sub-title was the word “independent.” Seeing a little one-paragraph AP item in a newspaper about the shooting of a small Negro boy in East Texas, Dugger packed his camping gear in his car for the first of many forays into the Texas hinterlands. The next issue of the Observer featured a grim story of joy-riding white youths who fired wantonly into buildings occupied by blacks. One of the bullets had killed the boy. Dugger’s account, filled with startling answers from law enforcement officials in East Texas, was dramatically punctuated with a front-page picture of the victim that Dugger had taken in the morgue.

The young editor’s first experiment in investigative journalism nearly wrecked his paper. Something on the order of half the East Texas subscribers promptly cancelled. The deficit leaped dramatically and the backers called for an accounting from their young editor. What they got in the next issue was another article entitled “The Devastating Dames” in which Dugger made it rather clear that though the editor was only 24 years old, he did not feel in the need of ideological counseling from his elders. The backers thereupon fell by the wayside until there was only one, a quiet, steel-willed Houston woman named Mrs. Frankie Randolph. She liked the idea of a “journal of free voices.”

In 1955-56, Dugger played a key role in breaking the land scandals in Texas and his struggling journal received its first national attention. As circulation rose, the Observer edged toward the financial break-even point. This was successfully avoided by doubling the staff to two. Dugger paid himself $110 a week. The other editor, William Brammer, received $100. By the time I arrived in 1958, the Observer was again threatening to break even. Dugger raised himself to $120 and I received $110. Mrs. Randolph’s aid now became more of a gesture of solidarity than an absolute necessity. Dugger’s journal had become a fixture in political Texas. In the 1960s the Observer balance sheets ceased to show red ink and, I gather, expenses have subsequently risen to meet income. I would not be surprised to learn that the current incumbents, Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott, receive $130 a week.

The New Journalism

As Observer editors came, learned, exhausted themselves, and left, Dugger’s presence sharpened the definition of his journal. In my judgment, the real story of the paper, and of its writers, lies in the relationship each of them had with the founding editor. Dugger may not have John Updike’s gift for metaphor, but in a quiet and unobtrusive way that only his colleagues understood and appreciated, lie played an absolutely crucial role in fashioning the ground rules for a new kind of expanded American journalism. It was one that went quite beyond the “who-what-when-where-and-why” of the old school to provide the essential background information necessary to coherent interpretation. Long before Norman Mailer wrote his celebrated account of the I960 Democratic national convention, long before Tom Wolfe and Hunter Thompson became the beneficiaries and proponents of “the new journalism,” Dugger developed and taught his editors the stylistic and conceptual basis of authentic, fair, but remorselessly interpretive journalism. It is time the story be told.

I cannot speak for the other Observer editors, of course (though the evidence of their gradual mastery of the new form on the Observer is easily discernible), but I can illustrate the process through an event that occurred to me in 1958. The very first news assignment I had on the Observer concerned a meeting in Austin of the highly publicized and eventually productive “Hale-Aikin Committee” to revamp the public schools of Texas. The heralded “Committee of Twenty- Four” was laced with men who possessed the political clout to get their own recommendations enacted into law.

But I discovered, from the otherwise empty press section, that the Hale- Aikin Committee was dominated by oil lobbyists whose chief intention, it became abundantly evident, was to argue with educators on the committee who wanted a wholesale revamping of the schools - one that would cost real money and put the ramshackle state school system on a genuinely professional basis. This cleavage on the committee, transcendency clear though it was, had gone unreported in the state press. I took down pages of revealing quotes and strode happily back to the Observer office. As I walked in, I summarized the meaning of the story for Dugger and then sat down to write it. I wrote like a journalist – and though I was in my twenties, I wrote like an old journalist. I based the story on quotes, until, paragraph by paragraph, the pieces of the mosaic were slowly pushed into place. It was a long story and when it was finished, I was pleased. Dugger, however, was not. A frown appeared as he read the lead and deepened as he moved laboriously through the succeeding sentences. Finally, he looked up and said quietly, “Larry, this is not what you told me — The Oilmen vs. The Teachers —it doesn’t come through. It is not here.” Defensively, I said, “Well, there are rules, Ronnie.” Hurriedly I found a key quote in the ninth paragraph and another one in the fifteenth. “The inference is pretty clear, don’t you think?” I asked. “What more can I do?” I asserted. “No oilman actually said that he was outflanking the teachers. No one was carrying a placard, you know.”

Dugger leaned forward earnestly and for the first time I heard the new philosophy of what is now widely acknowledged as the new journalism. “What you do,” said Dugger, “is write a story that explains — a kind of dope story. In the lead you just explain what is going on. Include whatever background on the oil connections of these men that you need to make yourself comprehensible to the reader. Don’t worry about attributing anything to anybody. That comes later in the story. Just tell the reader what really is going on and tell him right away. The rest of the story provides the structure of support you need. You’ve got the evidence, God knows. Just explain the real meaning right off the bat. Visualize that you’re writing an interpretative essay, with evidence.”

This was a strange new world, indeed. I struggled. Dugger edited. I rewrote. Dugger re-edited. After two hours, we were done and adjourned to Scholz beergarten for a celebratory beer. The right-hand side of the front page of the next Observer carried the story, with Dugger’s succinct headline: “Oilmen vs. Teachers.” The story made quite a few waves, as public demand for better schools was a genuine political reality in Texas and one in which a number of metropolitan editors participated fully. The Hale-Aikin committee began to function before a growing press gallery and, eventually - though the teachers did not win all their battles by any means - the new structure of state aid to the public schools was fundamentally sound, lasting and significant.

The story was not mine, however, it was Dugger’s. In some despair, I learned that it took months of hard work to learn how to write an interpretive essay that was both penetrating and fair, that both summarized clearly the inherent meaning of political events and contained adequate evidence to support the underlying interpretation. By the time I became reasonably competent, I was emotionally and physically drained by the 70-hour weeks, and by the constant life in the swamp of corruption that inundated political Austin. Like Brammer before me and Morris and Sherrill after, I quit when I had learned to write. Dugger had to find someone else to teach.

It is not my intention to diminish the achievement of that bizarre group of fellows called the “Texas Observer boys” or, as would follow later, the “Texas Observer girls.”

But I think all these writers would attest, in their own private ways, to the impact of Dugger’s ethical tenacity on our own little provincial literary world. Dugger inherited a cultural environment in which Speaker Sam Rayburn was teaching Lyndon Johnson that, in Mr. Rayburn’s famous words, “you have to go along to get along.” Dugger decided that too many people had been “going along” for too many generations. It was not the corruption of individual politicians that worried him —he did not celebrate when the land commissioner of Texas, Bascomb Giles, went to jail. Rather, he worried, and still worries, I gather, about the erosion of the culture itself, of the very fabric of shared values that alone can sustain a democratic society.

The electoral needs of embattled Southern liberals received his due respect, but not when those needs intruded upon more central needs of black Americans. Yet, even on this most seminal issue - one on which the Observer for years and years stood absolutely alone among Southern journals - Dugger’s specific posture was but a part of a larger purpose: to seek out the essence of political democracy, and locate the sources and modes of its corruption. In historical terms, his ethics are traceable to John Stuart Mill, his political vision to Jefferson, and his economics to the literature of European and American social democrats. But the environment he created — in the cavernous, disorderly office on 24th Street in Austin - was his own. There, near his fragile and beloved university, he became a pariah in his homeland, cussed and ostracized by the Tories, cussed and courted by Lyndon Johnson, cussed and be friended by Ralph Yarborough and the liberals.

I have known him most of my adult life and I am not the one to pass detached historical judgment on his journal or literary judgment on its writers, all of whom I have known for the better part of 20 years. They would be the first to concede that the sheer physical demands of getting out the paper left no time for polishing prose. The Observer has intermittently been strident, righteous, and badly written. It has also been wrong. It has —thank God — never developed what could be called a finished style - in the sense that the New Yorker or Time magazine have — for it has contented itself with Dugger’s original purpose, to be “a journal of free voices.”

One knows, intuitively, that the Observer belongs to the young. It should never have a wise and urbane staff, but rather an aggressive gathering of indignant muckrakers. Muckraking especially cultural muckraking —is hard work, work for the young. The Observer ought to get in trouble and stay there. And when its writers get sophisticated in interpretation and graceful in style, they ought to get out: they are too old.

I think it would be proper in this kind of piece to close with a story. In the early 1960s Willie Morris called me and asked me to meet him at Scholz, the Observer’s ex-officio conference room. Over the second pitcher, Willie divulged that he was leaving the Observer. “Why?” I asked.

“I’m worn out. ‘Plumb wore out, as they say.”

“That’s the reason,” I replied. “I wore out, too.”

As we were leaving, Willie asked, “How old were you when you wore out?”

“Thirty-one,” I said.

“I must have worked harder,” said Willie. “I’m twenty-nine.”

On the steps in front of Scholz, Willie said, with a touch of wonder:

“I don’t know how Dugger does it.”

Tags

Lawrence Goodwyn

Professor of history at Duke University and author of Democratic Promise, the landmark history of the Populist movement. (1990)

Larry Goodwyn teaches history at Duke University. His son, Wade, born in Austin during the family’s years with the Texas Observer, is currently a member of the Longhorn Marching Band. (1979)