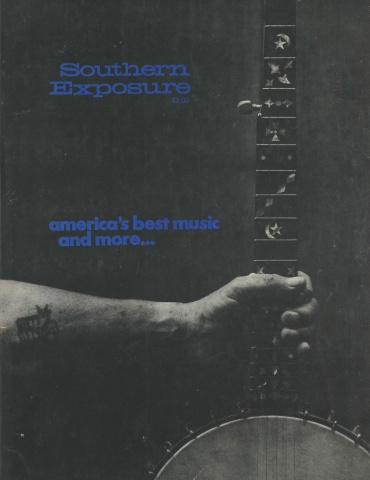

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 1, "America's Best Music and More..." Find more from that issue here.

Bruce Bastin's Crying for the Carolinas (1971) demonstrated the continued existence of the Piedmont blues tradition which has produced such notables as Blind Boy Fuller and Gary Davis (discussed in Bill Phillip’s article herein). Bruce’s fieldwork in the Piedmont also led to the discovery of several survivors of an earlier Afro-American musical tradition. Bruce introduced us to John Snipes, a banjo player, and to Kip Lornell, a young field worker who led us to John’s sister, Mary Poteat. Mary also plays the banjo and may once have been the best of those whom we have visited. Again thanks to Kip, we were able to meet Joe and Odell Thompson, cousins, who play fiddle and banjo together in a style suggestive of the Appalachian string bands. Kip also tracked down James Phillips “Dink” Roberts, a banjoist and guitarist some eighty years old, who has lived in Alamance County, North Carolina, most of his life. Bill Phillips directed us to Dink’s home in January, 1974, and since then Dink and his family have allowed us to record many hours of music and conversation on sound tape, video tape, and film. The interview below is excerpted from a lengthier conversation with Dink, his wife Lily, and son James, on February 21, 1974.

The existence of these pre-blues musicians is of some importance to the student of southern musical culture. The banjo, or some proto-banjo, is almost universally believed to have been brought to the New World by African slaves. Early written references to the banjo indicate its presence in the upper Piedmont in the 18th. century and it spread to the deep South somewhat later. According to Thomas Jefferson, the “banjar” was “an instrument proper to the blacks which they brought hither from Africa” (Notes on Virginia). Several black banjoists (and to our knowledge, no whites) are depicted in the late 18th and early 19th century American painting. Most of the instruments shown have three or five strings, one shorter than the others, and appear to be prototypical of the five-string banjo more recently “proper to” the Anglo-American mountaineer. It is evident that the instrument passed from blacks to whites in the last century. Little or nothing is known, however, about the styles and repertoire which surely made this same passage.

Among the mysteries which cloud this musical exchange are those surrounding the origins of technique. For example, one of the most common traditional methods for sounding the banjo involves striking down (i.e., towards the instrument) on one or more strings with the nail of the right forefinger. This method is known as “knocking,” “rapping,” “trailing,” etc., and has many regional and individual variants. Along the Blue Ridge in southwestern Virginia and northwestern North Carolina where it is most fully and artistically realized, this is called “clawhammer banjo.’’ The down-picking technique has no clear antecedent in European music and would appear to be of African or Afro-American origin. This speculation, vague as it may be, is consistent with the fact that all four black banjoists we have visited employ this method of playing. Since they all learned from Piedmont blacks whose musical lives extended well back into the last century, it is fairly certain that the development of down-picking predates the banjo’s currency in the mountains. Still all our informants share characteristics of style rather specific to the clawhammer region of the Blue Ridge.

The data which will prove black invention of the clawhammer style has yet to be gathered, and such matters may never be satisfactorily settled. Be that as it may, we can safely say that, with few exceptions, every truly vigorous American musical idiom has drawn from roots among black musicians of the Southeast. We are fortunate to have met and learned from Dink Roberts, his family and his contemporaries. There are doubtless many more such musicians scattered across the South waiting for folklorists and oral historians to come knocking.

Most of Dink’s early memories are housed in oft-repeated anecdotes, one or another of which usually serves to answer any question about the past. Like other forms of folk narrative, these memories possess some constancy of wording and structure in their retelling. Certain characteristics of Dink’s speech, its rhythmic cadences and two-fold repetition of phrases, find their way into his songs, and are of a piece with the patterns which crystallized in the country blues.

Dink is a skilled, sometimes inspired, performer and apparently his music once commanded great respect in his community. He plays finger-style (up-picking) as well as clawhammer banjo and the slide guitar with a pocket knife. His performances are casual; his tunes possess little internal structure, and his verses migrate freely from song to song. He often incorporates commentary and explanation into his songs without breaking stride. Lily sometimes accompanies his singing, and she and James are excellent dancers.

The conversation picks up with a discussion of two members of the band Dink played in, George White (another banjo player) and John Arch Thompson (a fiddler and Joe Thompson’s father). They played for dancing (“hands up eight”), sometimes as often as six nights a week—three for blacks and three for whites.

Cece: Did John Arch Thompson and George White learn from you?

Dink: I learned from them. See, they old, way older than me. I’m 79. God has blessed me. That’s the truth. Going now [to play] in a few minutes. Gonna drink this one. Y’all ain’t in no hurry?

Tommy: No. Did you learn from your uncle, too?

Dink: Yeah, I learned from my uncle, man raised us, George Roberts. Weren’t but three of us. My mother died when I was nine years old. He took us and raised us. Weren’t but three of us, and he treated us all alike, and it didn’t make no difference between his’n and us. That’s the truth. [He] had eight children. They played [music], too.

James: That thing ain’t taping now, is it?

T: Yeah. We want to tape the whole family history, not just the music. (General laughter).

D: Now if I had a guitar, him [James] could play a guitar. Right over there, that boy. He can go on a guitar. He knows them new pieces. I don’t know nothing but old pieces. I used to play guitar. I never will forget it. My second wife [Jewel], she bought me a guitar, brand new guitar, and I never will forget it long as I live. I said, “Well.” And she said, “Now you ain’t gonna open it ’til Christmas morning.” I said, “You know I know old Santa.” She said, “Yeah, but I’m not gonna let you take it out ’til Christmas morning.” Well, Burch’s Bridge, my brother-in-law lived across over there. Moon shining bright as day. There’s two men, white men, and two white women—I’m telling you the God’s truth—says “Uncle,” says “How about playing that piece you was a coming down the road playing a while ago.” I said, “I just got a guitar for Christmas,” and I says, “Old lady didn’t want me to take it ’til Christmas morning.” And I said, “Well, you know I know old Santa Claus,” like you know. And I was playing “Careless Love.” [They] said, “Well, I’ll tell you what I’ll do if you just play the piece coming down the hill there.” And they had liquor and everything. Had a little old paper cup. Say, “Ya have a drink friend?” And I said, “Too much raised to ’fuse it!” I’m telling you I played two tunes, and they handed me six bucks. That’s the truth. But I could play then; I can’t play now.

C and T: Aw, sure can.

J: That beer makin’ him talk ain’t it. Get another one, he’ll be right, won’t he.

C: Did you ever hear a piece about someone named Riley?

D: Riley?

T: Breaking out of prison. [In some versions of “Old Rattler,” Riley escapes from tracking pursuers by wearing his shoes backwards.]

D: Use to play it, but can’t play it now. Played it for a fellow—he’s dead and gone now. He was a good man walked on, in two shoes. But he didn’t give a dog. Walt Weaver was a good man as walked in two shoes, but he didn’t give a dog. He use to go to school on a jackass, just a jackass. Now, I don’t mean no harm by saying that. But he’d get on a jackass and ride it plum through school ground. That’s right. (Laughter) ... for fun, just for fun. Dead and gone now. Good a man as walked in two shoes. Just mischievous, just mischievous.

J: Did everything in the book. He could dance, too. I learned to dance from him.

D: Talk about buck dance, he could go, he could go. He was a white fellow but he could go. Well, getting bout right now. Old banjo done got dusty and everything. I been telling James and them, “tighten it up and everything.” But, just don’t want to do it. [Tunes his banjo]

C: In that Riley song, did Riley get away?

D: (Laughs) Yeah, Riley got away .... He could go.

C: Do you remember where you learned it?

D: Ah, Lord knows it’s been so long. Don’t know now how long it be. My memories ain’t like they use to be.

[Dink plays “Laid Poor Jesse in His Grave.’’ He learned this song from his brother Johnny Roberts who was much older than he. As well as learning from George Roberts, the great uncle who raised him, Dink played and learned from George’s children. The first piece he heard from his family and the piece he learned was the “Fox Chase.’’ He played that one next for us. “Roustabout,” a song known in the Blue Ridge Mountains, was the third one that Dink played.]

T: What does “roustabout” mean?

D: Well, I just don’t know.... It means a whole lot but I just don’t know the meaning of it, you know. I tell you, I learned them old pieces lookin’ at the other people play. I had the music on my mind, you know. I’d go to town and hear somebody playing, you know. Walk up— I’d say, “I’ll play that.” Get out to yourself, you get out to yourself and you can play it. But if you get with someone else and—they cut you off.

T: Right. Lily, I’m glad you made it back.

Lily: Yeah, I’m back. Stuff was high in Byrd’s today. Took every one of them there tickets to get groceries. Thirty-one dollars—that left me with nothing.

C: For the rest of the month?

L: That’s the truth—I’ll have some next month. [To Dink] I got you some bacca but I can’t get you no snuff.

[Dink plays "John Lover’s Gone.” This title and some of the verses are also known in the mountains.]

John lover’s gone;

John lover’s gone to war.

John lover’s gone;

Ain’t that lucky, too?

Yeah, Momma told me

Some folks say the Devil’s dead,

But I saw the Devil the other day

Kickin’ up the dust to get away.

Danville’s ....

Yeah, who been here since I been gone?

Little bitty girl with a red dress on.

She can do that trick all night long.

(Dink laughs)

Yeah, my Momma told me ’fore she died

She gonna buy me a rollin’ hill.

Some folks say the Devil’s dead;

Caught the Devil the other day over in Danville.

He kickin’ dust way over in Danville.

Oh, lord, . . .

C: Where did you learn that one, Dink?

D: Lord, that’s been years and years ago. I used to go to parties and things. The other man been playin’ the banjo. When I’d walk in the house he’d lay his banjo down. Give it to me.

C: Since you were the one who could play best.

D: Yeah. Be in a room about like this here, and ah—He’d come in; he’d be playin’ the banjo. I’d come in with mine, he’d lay the banjo down. Then he’d go to frolickin’—you know ‘‘hands up eight?” That’s right! Wouldn’t be a cross word said. But now you carelessome now, somebody get killed. (Laughter) That’s the truth. That’s the God’s truth.

L: Lord no. You can go to a ball game ....

D: Up to my fingers and down to my toes,

Where many quarts and gallons goes.

Boys, if I don’t drink it all, you can have some.

I played with John Arch [Thompson]—he was an old man like me—[for] gatherings and frolics and things like that.

C: Square dances?

D: “Hands up eight and don’t be late.” George White played banjo [like me]. Everybody plays music got a different sound. He could go. He married my first cousin, George White did. Oh Lord, [we played] in different places, different places. In people’s houses, people’s houses.

T: When you played one set did you change tunes while people were dancing? [According to Dink and John Snipes, a set could last a full hour!]

D: No. Run a set—you play one piece for that set. They get up another set, you play another piece. Lily dances so—

C: When was the first time you saw Lily dance?

D: She knowed my first wife [Sara]. She did, that’s the truth. Did you see her picture? I married and married again. I had three women and all of them sweet and everything, but the Lord knows best.

Tags

Cecelia Conway

Cecelia Conway is writing her dissertation in folklore for a Ph.D. in English at the University of North Carolina. (1974)

Tommy Thompson

Tommy Thompson is a Chapel Hill-based writer, actor, and musician who plays banjo with the Red Clay Ramblers. Thompson and the Ramblers performed in the world premiere of Sam Shepard’s drama A Lie of the Mind at the Promenade Theater in New York City from December 1985 through June 1986.