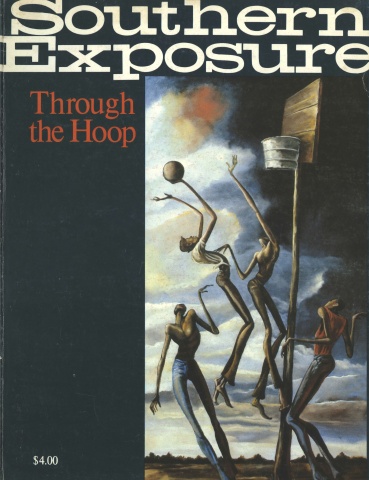

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 7 No. 3, "Through the Hoop." Find more from that issue here.

“Pull over here,” she says. There is a sign by the side of the road — MONEY, MISSISSIPPI. Across the highway, pointing down a dirt lane, is another sign — SWEET HOME PLANTATION. Up ahead on a sagging, unpainted, wood-frame building are the hand-lettered words GROCERY STORE. Farther on is a mobile home propped on cinder blocks. POST OFFICE. And finally, at the edge of Money, the tallest building, THE COTTON MILL.

A railroad track runs alongside the highway, and beyond are rows of green bushy plants flecked with white. A morning mist hovers over the plants. “I was born out there,” she says, pointing out the car window toward the cotton fields. “On the plantation. We lived way down in the fields. Now they build the houses closer to the road, but in those days, before anyone had an automobile, they built them in the middle of the fields. My first memory is of my uncle leaving home. My mother stood in the yard and watched him walk through the fields. You could see the top of his head moving between the rows. When he reached the road and turned left, my mother said, ‘Well, your uncle’s leaving home.’ He lives in Oakland now.

“I started chopping cotton when I was 10. We used a long hoe called ‘the ignorant stick.’ At five in the morning the plants were cold and wet and they soaked your clothes as you moved down the rows. It was a terrible kind of chill. But by late morning the sun would be hot. Lord, it was hot! You could see the heat waves simmering behind you. ‘Hurry up,’ someone would shout, ‘The monkey’s coming!’ And then others would pick up the shout, ‘The monkey’s coming, the monkey’s coming!’

“Lord, those rows were long! You could chop for a whole week and never finish a row. I got paid $2.50 a day for 12 hours. I never understood why my father made me chop until now. He wanted me to be independent, and it worked. I call him my father, but he really was my grandfather. I was born with red hair, gray-green eyes, and skin so pale you could see my veins. My real father looked at me and told my mother I was not his child. Three days later he took a boat across the Tallahatchie River from Racetrack Plantation, picked me from my mother’s arms and carried me 15 miles to my grandparents’. They raised me. I hold no animosity toward my father. It was just ignorance. Later on he realized that I was his child.

“We can go now.”

It is nine in the morning and the temperature is 92 as the car heads south to Greenwood. Inside, however, the only sound is the hum of the air-conditioner. The road runs through fields of cotton. Occasionally, there is a shack alongside the highway.

“They painted sharecropper homes all one color, according to the plantation,” she says. The ones along here are a faded red. “Plantation life was not bad, really. Every holiday there would be a picnic. They would dig a hole in the ground and start a fire, then throw a fence over the top and roast a pig on it. The owners supplied the food. Each plantation would have its own baseball team and the men would play against each other. If someone died on the plantation everyone would stock that person’s house with chickens and greens and stuff, and if it was a woman who was left, they would come and pick her crops for her. It was a warm relationship. The hardest adjustment to make when I moved to the city was learning I could not be friendly, that you did not sit beside someone on the bus and talk.

“This was a dirt road when I was a child. There were always people walking up and down, usually couples holding hands. They walked from Money to Greenwood and back, a distance of 20 miles. They were courting. Now that is heavy courting. Then people got automobiles, and the Ku Klux Klan started riding again. Right over there is where Emmett Till was lynched. You remember Emmett Till, in the ’50s? He was the 14-year-old black boy who supposedly whistled at a white woman in a grocery store. That night they dragged him from his uncle’s home, tortured and shot him and dumped his body in the Tallahatchie.

“I remember once my cousin came to visit, and she got off the bus at the wrong stop. It was already dark so she started to walk. Two white men drove by. They turned around and came back toward her. She knew what was going to happen so she ran into the cotton fields and lay down. They searched for her for hours but couldn’t find her. It was the most frightening experience in her life, she said. I imagine it was. I never had any experiences like that. I try not to put myself in that kind of position.”

The car crosses the Tallahatchie River into Greenwood’s city limits. A tree-lined esplanade divides the main thoroughfare, Grand Boulevard. On both sides are massive mansions, aging and untended. From the second-floor balcony of one hangs a Confederate flag.

“They raised me well,” she says. “My grandparents, I mean. It was not the same as having parents, of course. They were not affectionate. I never remember any warmth, any feeling that they really cared, but I never wanted for necessities. And they were strict. Very strict. Why, they would not even let me receive company until I was 16. Whenever a boy called the house and asked to speak to Miss White, my mother — my grandmother — would answer the phone and say, ‘I’m the only lady in this house who receives company, and I am sure you are not calling me because I am a married woman.’ And they would hang up quick. I appreciate that kind of thing now. It taught me self-respect. But then I just wanted to get out of the house. That was why I turned to sports. It was the only way I could stay out past five o’clock. And I was good at it, too.

“When 1 was in the fifth grade I played on the high school’s varsity basketball team, and when I was 16 I was running track for Tennessee State. Sports was another kind of escape, too. As a child I was an outcast. Blacks were prejudiced against me because I was so light-complexioned. Parents would not let their kids play with me. They said horrible things about me. In school, whenever there was a play or a dance, the instructors would choose the black girls with wavy black hair, starched dresses and patent leather shoes. It did not matter that I could sing and dance better. I was too light and had this funky red hair, and I was always running around in overalls with a dirty face and no shoes. The only way I could get any recognition was through sports. Now those same parents want me to stop by their house to visit a spell whenever I return to Greenwood. I can’t do it. I feel funny. I remember things. Lord, I had a miserable childhood. But I survived. Baby . . . I have . . . survived.”

The car passes over another river, the Yazoo, which is the color of mud. It smells of mud. It barely flows. A twig floats without moving. Greenwood (pop. 22,500) lies at the confluence of the Yazoo and Tallahatchie in the green heart of the Mississippi Delta. The city still bills itself as “The Cotton Capital of the World” and is building on the outskirts of town a replica of a pre-Civil War plantation. Downtown, the city’s streets and sidewalks are littered with balls of cotton that have spilled out of trucks and warehouses. Although cotton is no longer the only crop harvested here (soybeans and rice are increasingly popular), it remains a dominant force in the area, and the attitudes of the Old South endure.

Blacks cross the railroad tracks that divide the black and white communities in order to shop, and they can dine and dance without incident at the Ramada Inn out on U.S. 82 and Park Avenue. Still, there are plenty of white-owned restaurants and bars where blacks do not venture — which is why it is so noteworthy that the city, not to mention the entire state, declared March 12, 1972, “Willye B. White Day” in honor of a 32-year-old black woman who had passed her youth on a nearby plantation pulling “the ignorant stick.”

On that day the city was festooned with banners and bunting and larger-than-life photographs of Miss White. There was a motorcade. Miss White rode in a shiny Buick and waved to the townspeople lining the streets and shouting her name. The mayor gave a speech in which he claimed that the city of Greenwood was proud to have once been the home of Miss White. She was ushered into the town library, the same library for which her grandfather had once been the gardener and where she could never have gone years before. Inside, the walls were papered with her photograph.

Willye had warranted such an occasion because of her athletic achievements — she has been one of this country’s premier competitors in track and field for 20 years. She first won notice in 1956 when, as a 16-year-old, she surprised the experts by winning a silver medal in the long jump at the Melbourne Olympics. Her mark of 19 feet, 11 3/4 inches was bettered only by Elzbieta Krezsinska of Poland. This would be her best Olympic showing, but she made every Olympic team for the next 16 years, finishing twelfth at Rome, twelfth at Tokyo, eleventh at Mexico City. At Munich she was eliminated in the qualifying round.

In 1964 she won a silver medal at the Tokyo Games as a member of the 400-meter relay team. In that same year she broke Wilma Rudolph’s indoor 60-yard-dash record of 6.8 seconds with a 6.7. It was not until she was 28 that she gave up sprinting. She won four medals in the 1959, 1963 and 1967 Pan-American Games, and has 17 national indoor and outdoor track titles to her credit. Her 17th and last U.S. title came in 1972 when she won the long jump with a leap of 20 feet, 6 1/4 inches.

Willye’s fame lies less with any single achievement, record or medal than it does with the longevity of her career. The mere fact of having competed all those years is overwhelming. Willye says of herself, “I am the grand old lady of track.” On April 30, 1971, a story in the New York Times suggested that “women’s track and field began with Willye B. White.”

She traveled around the world twice and has competed in scores of foreign countries. She has been better remembered as a goodwill ambassador to these countries than as a victorious athlete. In the People’s Republic of China she was a favorite of both its athletes and citizens, and in Moscow she taught the male Russian athletes how to rock’n’roll. She has dated an Italian nobleman, whom she almost The Indoor National, Oakland, married, and American movie actors like Bernie Casey, who was once a professional football star. Among her good friends were some of the Israeli Olympians murdered in Munich. In 1966 she was cited for “fair play” by UNESCO and, along with other athletes, received her award in Paris amid much pomp and circumstance. The ceremony took place at UNESCO headquarters. A UNESCO official said, “Her poise and charm made her the star of the ceremony.” She has been elected to the Black Hall of Fame in Las Vegas and served on the President’s Commission on Olympic Sports.

For the last 19 years, Willye White has lived in an apartment on the South Side of Chicago instead of Greenwood. She holds a position as a health center administrator with the city and trains less often now. At age 39, she leads the cosmopolitan yet subdued life of an attractive, independent bachelor woman. She says, “I can go anywhere, talk about anything. My whole personality has been affected by my travels. My travels have broadened me. When you’re confined to one area you think the whole world is the same.”

Miss Willye B., wearing cut-off jeans and a loose-fitting white blouse, sits on a straight-backed chair on the front porch of her grandparents’ home and sips from a can of Tab. She had come to Greenwood thinking it might be for good. She was prepared to surrender her apartment in Chicago, quit her job, abandon her ambition of competing in another Olympics, give up sports, give up her lifestyle, in order to nurse back to health the 83-year-old grandfather who had raised her and who was dying in a small house on East Percy Street. She raises a hand to adjust the kerchief around her head. Her hair has been corn-rowed. She stares at the street and says, “Whenever I would talk to him I would say, ‘Now Daddy, don’t you die while I’m gone, you hear.’ These old people, you know, they’re like children. He had lost the will to live. I had come back to give him the will. He had been in the hospital and not moved for days. He had a 105 degree fever. I stayed up all night washing him with cold towels to bring down the fever. The next day he was siting up, smiling, laughing with me.”

She sips from the can, staring blankly at the street. There is only a dirt curb for a sidewalk. The houses are set close together and close to the road, some of them separated by picket fences, and are alike — long, narrow, some unpainted, some sagging this way and that like the deserted barracks of an army. Their fronts are dominated by porches, often screened. Now, in the afternoon of a scorchingly hot day, almost every porch is occupied, mostly by older men and women with dark skin and steely white hair. They stare at the street as if expecting, at any moment, an event. A passing car. Children returning from school. A dump truck delivering dirt.

Parked in front of the house where Miss Willye B. sits are a late-model Buick and a Cadillac, both with California license plates. They belong to her uncles, the Buick to the uncle she had seen leave home when she was two years old and whom she’d seen only once since. He is a husky man with a gold tooth. Hanging on the wall between them is a flyswatter. Inside the house there is the slapping of backless slippers against a linoleum floor. There is the sound of women’s voices, hushed, and then the dialing of a telephone, and now a man’s voice inquiring about a telephone.

“He was a man’s man,” says Miss Willye B. “In the South, you know, when older blacks are talking to whites they have a habit of taking off their hats. They shuffle their feet a lot and look down or off to the side, but never at a white man’s eyes. My father, now — my grandfather, I mean — he never took off his hat and he always looked white people in the eye. When I realized what he did — I was only a child — I began to practice it in front of a mirror. We didn’t get along then. He was a stubborn man, but as I got older I realized how similar we were. When he got sick I started commuting between Chicago and Greenwood.

“I could live in Greenwood, you know. Yes I could. It is not the same as it was during the freedom marches. You don’t fear personal injury anymore. And the other kind of thing I can handle. For example, when my grandfather passed I went to the doctor’s office to find out the exact cause of death. The receptionist there was hostile. Finally, I said to her, ‘Now listen, Miss, I think we have a misunderstanding here and we had best straighten it out.’ We did.

“I would have come back to live here. I feel I am what I am today because of my grandparents. If I could give them some happiness by coming home, I was willing to do it. I have roots. It does not matter how far I have traveled and where I live. Sometimes I envy the younger athletes. They just take off anytime they want. They never worry about returning home. I would like to be like that sometimes, and then other times I am thankful I do have roots.”

She flicks a fly with her hand and her silver bracelets jingle. Her fingers are long and thin and adorned with sparkling rings, metals and precious stones of various hues. Her nails are frosted pink. Around her neck she wears assorted gold and silver chains and pendants.

“God has it all planned,” she says. “He does not give you burdens you cannot bear. I was only home a few days when my grandfather passed. And then my brother came home and had a seizure right on the kitchen floor. He would have died, too, if it had not been for me. And I said, ‘Oh Father! Oh Father! what have you in store for me next!’ All I could think of was getting out on the track again and running and running and running and letting the tears come.”

[Break]

Ah ...Willye . .. leaps ... hangs ... lands in a spray of sand. She sits in the sand like a child, legs outstretched.

Behind her, Rosetta Brown, dark, plump, wearing slacks and a jersey, gets down laboriously on all fours and begins to measure the jump with a tape.

Two blacks in their late teens watch from the cinder track that surrounds the football field and long-jump pit at Greenwood High School. Home of the Bulldogs. One of the youths is muscular, athletic-looking, the other thin, knowing, wearing purple shades. The athletic-looking youth says, “I heard Miss Willy B. was back so I come to watch.”

Willye takes off her track shoes and stands up. She is five feet, four inches tall, 130 pounds. The muscles in the front of her thighs are so developed they partially obscure her kneecaps. Her stomach is flat. She is wearing a kerchief, a Pan-American Games T-shirt that has been cut off just below the bust, exposing her navel, and tight-fitting track shorts. Her toenails are painted pink. The youth with the purple shades stares as she dusts the sand off her rump and the backs of her thighs. He says, “My main interest is Miss Willye B., too.”

Whenever Willye works out, she is watched by boys. They follow her to the weight room, where she can squat upward of 380 pounds; then to the football field, where she sprints from goalpost to goalpost, her thick thighs writhing and her knees rising almost to her chin; then to the track where she takes each of the 10 hurdles with an effortless leap and a rhythmic crunch of her feet; and finally to the long-jump pit where she concludes her workout. After she leaves a segment of her workout, a few boys remain behind to imitate her just-completed feats. They try to heft the weights she had mastered, or leap the hurdles she had cleared, and when their feet get tangled and they tumble to the cinders they are jeered and hooted at by their friends. They laugh at themselves, too, when they fall, because in their mimicry of Miss Willye B. there is no desire to equal or surpass her efforts. They are merely trying to show how inadequate they are by comparison.

Willye resumed training shortly after the death of her grandfather. Since she promised her grandmother, a gaunt woman with quivering hands, that she would not leave Greenwood until a tombstone had been arranged for, she is conducting her workouts at Greenwood High. She could never have used its facilities years ago. But the school has been integrated, and now as she works she can see on the practice field the Bulldogs’ integrated football team going through its paces under the watchful eyes of black assistant coaches and a white coach, heavy men. The head coach, dressed in shorts, is only too happy to make available the school’s facilities for Miss Willye B. He seems to have little choice in the matter. Willye approaches him during a coaches’ meeting and says, “Coach, I want to use the weight room now.”

Walking toward the weight room with the coach, Willye smiles and says with only a hint of a drawl, “Say, Coach, didn’t you play at Mississippi College?”

The coach lowers his head and says, “Yes, I did, Miss Willye.”

“I heard you were some kind of football player.”

Watching from a distance, Rosetta Brown laughs. “That Red, she’s something else. She gonna have him all over her in another minute.”

Willye’s workouts are conducted during the hottest part of the afternoon, and when she is in Greenwood, Rosetta, her childhood friend, always comes along. Rosetta sets up the hurdles on the track, spacing them just so at Willye’s instruction, and then Rosetta rakes and hoes the sand in the long-jump pit as Willye prepares her jump. Finally, at Willye’s urging, Rosetta may begin to train, too. Not for any international competition, but merely to lose weight. She begins to jog. While Willye lopes gracefully over the hurdles, Rosetta huffs and puffs around the field with tiny steps. Passing Willye, Rosetta calls out in a high voice, “Oh, Red! I’m gonna be a traffic stopper again!” and plows on. Willye smiles.

Their lives, once concentric, have long since branched off on different tangents. Willye pursued sports, traveled, became famous, while Rosetta remained at home, married, had five children, saw her husband leave, and took a job as a supervisor in the cafeteria at Mississippi Valley State University. Once Willye invited her to Chicago. Rosetta stayed only a few days and returned to Greenwood. “I didn’t like the city,” she says.

“Rosetta has never traveled,” says Willye. “I’ve experienced things in my life she would never see in her world. Whenever I get the chance I like her to share in some of those things. They are not big things, but they are experiences she can talk about for the rest of her life.”

Although Willye’s life may have been a succession of victories, Rosetta’s has not been entirely devoid of them. She has raised her children and participated in civil-rights protests in Greenwood. “She was a freedom marcher,” says Willye. “On one occasion she was attacked by police dogs.

“I look at Rosetta sometimes and think, that could have been me. Sports gave me an escape. My mother — my grandmother — was against my being in sports. But it kept me off the street. The time I spent at practice wore me out. If I needed 20 hours of sleep to compete successfully then I got it. And I learned early that to survive in sport I had to be a thinker. I was better organized than most girls my age. I knew what was best for myself. That is one reason why I turned from sprinting to the long jump. It is very technical. It requires strategy, thinking, not just power. The other reason was that I saw for every 500 sprinters there were only two long jumpers. I played the odds. It was easier. Long-jumping is something I could do successfully when I became older. When I was younger I had the talent, the determination, the hard work — and no coaching. I have learned more in the last few years than I did in the previous 25. That is why I am still competing. But nothing is forever. I do not expect to jump forever.

“The hardest thing for me to do when I quit will be to find some way to fill the hours between four and seven p.m. Those are the workout hours. But I will be able to quit when the time comes. Some people say I am afraid, that time has passed me by and I am still hanging on. I see athletes I once competed with, and they say, ‘Willye, when you gonna quit? You’re too old.’ And I say, ‘You are the same age as me, why did you quit?’ And they say, ‘Well, I got married and I had kids.’ ‘Well, I am not married,’ I tell them, ‘and I don’t have kids and I am not 50 pounds overweight like you are.’ I know my body and its capabilities.”

When Willye completes her final workout before returning to Chicago, she walks over to the football coach to thank him for his kindness. The coach is standing among uniformed players. He is shouting instructions to the part of the squad that is scrimmaging. A few parents, all white, are standing on the sidelines. Willye, wearing shorts and her cut-off T-shirt, slips between the players, is dwarfed by them and their grotesque shoulder pads. She taps the coach on the back; he whirls around and seeing her there smiles. She says something, shakes his hand firmly and gives him that dazzling smile. She slips out from between the players and walks toward the car. The eyes of everyone — players, coaches, parents — are on her.

“They are so friendly in the South,” says Willye. “In Chicago I always make sure I’ve got protection. Eventually, I will come back to Greenwood. I can see myself as an old lady living on East Percy Street. I will get up at five o’clock and go stand on the porch to watch for the garbage truck. Maybe I will go out to my garden and sprinkle dust on the beans and then go inside to prepare breakfast, lunch and dinner, all at the same time. Then I will go back outside to take care of everybody’s business on the street. I will sit on a straight-backed chair on the porch and nod. My head will nod down to my chest until I am asleep. That is it. My life.”

Tags

Pat Jordan

Pat Jordan is an experienced writer who once played for the McCook Braves, a Class D baseball team in the Nebraska State League. This article, originally written for Sports Illustrated in 1975, appears in the excellent new anthology on women’s sports entitled Out of the Bleachers, published by The Feminist Press. It is reprinted here by permission of Dodd, Mead & Company. (1979)