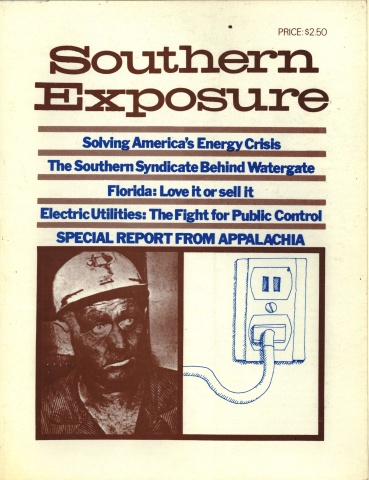

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 1 No. 2, "Special Report from Appalachia." Find more from that issue here.

It has been a long time coming, but the South is rising again. This time the weapons are economic and political, based upon the natural resources of the South, the population boom in the sun belt, and the largesse of the federal treasury; and this time the war looks like it will be won.

Perhaps it has been won already—at least for the wealthy few who are beginning to flex their muscles at a national level. The ascendency to power of Lyndon Johnson and then Richard Nixon has solidified a position for the South in the corridors of power beyond anything the nation has seen in recent years, and if Nixon now remains relatively undamaged by the Watergate disclosures, it seems likely that this power will increase in the next three and a half years. I would go even further: if Nixon remains undamaged, the political base which the South has so far built will continue on beyond the present administration and will assert itself for the next political generation at least. Whether the next president is Connally or Reagan, Howard Baker or Governor Askew, or even Agnew or Harris or Mondale, he will be in debt to the power of the Souht and will serve in those interests.

Now I should say right away that the power of this magnitude is not confined; it must be shared. In this case, it is shared with the Great Southwest, into which the South blends so naturally, forming a power belt from Southern California through Arizona and Texas down to the Florida keys, a geographical area which I have called the Southern rim. Of course the Eastern Establishment continues to have lots of power. But something is clearly shifting in our national “power structures,” and awareness of the old and still potent centers should not blind us to the major role of new and expanding components.

The power of the Southern rim is built—to oversimplify just a bit—upon oil, aerospace, defense, real estate, and tourism, all of which have gained importance only since the Second World War and are now sedimented into the economy.

Independent oil producers—the H.L. Hunts and John Paul Gettys, as opposed to the international giants like Exxon and Mobil—are based chiefly in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana, and their spectacular development of the area’s underground riches has given them a wealth which in the last two decades has found its way increasingly into politics, at both the local and national levels. Among the most important today are companies like Union Oil (Los Angeles), Occidental (Los Angeles), Atlantic-Richfield (Oklahoma), and Sun, Gulf, Ashland, Continental, Coastal States, Getty, Mesa, and America Petrofina (all Texas)—and each of these, in turn, spreads out into other Southern regions, from the coalfields of Appalachia to the off-shore wells of Louisiana.

Aerospace, similarly, has tended to be a Southern rim phenomenon, to the benefit of such firms as Lockheed (California), Rockwell International (California, Texas), Hughes (Texas, California, Arizona), Texas Instruments (Texas), and Electronic Data Systems (Texas); with the boom in space spending has gone the boom in economic and wide-ranging political power for these industries. Defense, which is closely allied to aerospace, reflects the same pattern: of the ten firms which are perennially at the top of defense earnings, seven are chiefly Southern rimsters—Lockheed, General Dynamics (Massachusetts, Texas, Florida), McDonnell-Douglas (Missouri, California), Rockwell, Litton (California, Mississippi), Hughes, Ling-Temco-Vought (Texas)—and many other defense giants have heavy Southern interests (Tenneco, AT&T, Textron, Honeywell, United Aircraft, etc.) (For a comprehensive and detailed account of specifically Southern defense interests, see the Spring 1973 issue of Southern Exposure).

Real estate and tourist corporations, by the nature of their ventures, are considerably more local than these other interests, but it is inevitable that they predominate in the Southern rim, where the great population explosion has taken place in the last 20 years (especially in southern California, Arizona, and Florida) and where most of the nation’s leisure time playgrounds (Las Vegas, Palm Springs, and Miami Beach prominent among them) are located.

The people who represent this considerable power base have been dubbed—first by Wall Street and then by popular commentators—“cowboys,” to distinguish them from the old-money, settled-family people of the Eastern Establishment, who are naturally called “yankees.” And though this smacks of a certain regional snobbery, there are particular characteristics which distinguish these Southern rimsters that fit in nicely with the image of the free-wheeling, frontier-oriented, live-for-today, tough-and-swaggering cowboy. They are new-money people, the first generation rich, many working their way up from poverty, and they tend toward the nouveau-riche traits of flashiness, extravagance, excessiveness—Judge Roy Hofheinz comes to mind, and H. Ross Perot, and H.L. Hunt, and Glenn Turner, not to mention their political spokesmen like Strom Thurmond, George Wallace, Ronald Reagan, and (supremely) Lyndon Johnson.

They like to think of themselves as self-made men, wrestling fortunes out of the hard land—though in truth, they are almost all government-made men, depending upon oil depletion allowances and (until recently) oil quotas, on enormous defense and aerospace contracts from Washington and a concomitant cost-plus banditry, and on beneficial federal rulings for air routes, radio and TV licenses, rail shipments, and the like. They tend to a notable degree to be politically conservative, even retrograde, usually anti-union, anti-black and anti-chicano, anti-consumer, and anti-youth, and many of them are associated with either the hate-mongering revivalist sects or the professional anti-Communist organizations (John Birch Society, Minutemen, Liberty Lobby, American Security Council). And they often seem to have developed a self-serving ends-justify-the-means amorality, a disregard for the usual niceties of business or political ethics, and they are therefore frequently connected with shady speculations, political influence-peddling, corrupt unions, and even upon occasion with organized crime.

Watergate Tricksters

Watergate, by a neat coincidence, has offered us a window on the mentality and operations of the Southern rim cowboys, and it is worth pausing to look through it for a moment. Much of the money that found its way into the Watergate burglars’ pockets and into those of other saboteurs and infiltrators came from the Southern rim: at least $100,000 came from Texas oil, raised by Gulf Resources president Robert Allen and delivered by a Pennzoil vice president, and an additional $25,000 was delivered from the Florida holdings of Minneapolis millionaire Dwayne Andreas. Additional funds, perhaps as much as half a million in all, were raised from California richies and controlled by Nixon’s personal attorney, Herbert Kalmbach, a wealthy Southern California lawyer and businessman; it is a measure of his Southern rim milieu that his comrades in the ultra-prestigious Lincoln Club of Newport Beach, California, see nothing either shocking or questionable in Kalmbach’s sabotage performance (N.Y. Times, June 19, 1973).

Overseeing these funds in Washington were people like John Mitchell (a ringer: from New York and Wall Street), Frederick LaRue (a rich Mississippi oil man), Robert Mardian (Arizona), Jeb Magruder (California by adoption), Dwight Chapin (California), Gordon Strachan (California), and above all (with the possible exception of Nixon, a Southern Californian) the leaders of the California Mafia in the White House, H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman. Not all of them were rich cowboys by any means, but they all seemed to have shared in the cowboy mentality of selective amorality, of justifying sleazy and illegal acts if they are self-serving, of using enormous wealth to satisfy private interests. And they all seem to have partaken in the latest form of anti-Communist hysteria, the fear of the radical forces of the Left whether violent or peaceable, the vision of Weathermen and Panthers under every bed—and they used this paranoia to justify an enormous campaign of repression, beginning in 1969 with Mitchell’s ascendancy to the Justice Department, through the series of grand juries, conspiracy indictments, wire-tappings and infiltrations, right down to the sabotage of the McGovern campaign, of which Watergate was only a small part.

Watergate was not just another example of the dirty game of politics. Watergate was a deliberate attempt to destroy some of the inherent values of the two-party system. And it would not have happened without the emergence of the Southern rimsters and their cowboy mentality into positions of high political power.

But the influence of the Southern rimsters goes far beyond the Watergate affair and remains even with the departure of the leaders of the California mafia. Let us look at some of the people whom Nixon has chosen to put into positions of power. At the top are the people who manage the budget, from which all else flows: Roy Ash, a defense-industry millionaire from California, and Frederick Malek, a tool-manufacturing millionaire from South Carolina. Next are the Cabinet rimsters: Claude Brinegar as Secretary of Transportation (California, Union Oil executive), Caspar Weinberger as Secretary of HEW (California, Republican politico), Anne Armstrong as Counselor to the President (Texas, rich Republican politico), Frederick Dent as Secretary of Commerce (South Carolina textile millionaire), William Clements as Acting Secretary of Defense (Texas oil millionaire), Robert Long as Assistant Secretary of Agriculture (California, Bank of America executive). Then follow the Republican National Committee chiefs, exercising even more power in the wake of Watergate: George Bush (Texas by adoption, co-founder of an oil company), Janet Johnson (California rancher), and general counsel Harry Dent (South Carolina GOP politico). The power of the rimsters is so strong here that Northern and Midwest Republicans have even complained publicly of a “Southern Mafia” (N.Y. Times, March 27, 1973). And we must not forget the two powerful swing-men on the Supreme Court, Lewis Powell (Virginia) and William Rehnquist (Arizona), both thoroughly imbued with cowboy conservatism, though the former more genteel, the latter more crude.

Sticking just to the formal and official positions in Washington, however, does not give the full picture of the Southern influence. For the people who are most potent are Nixon’s closest friends, the small circle of trusted companions which he has kept around him over the years, and whose advice he seeks both in times of normalcy and in times (as the present) of crisis. A few are yankees—though up-from-poverty yankees—like William Rogers and Robert Abplanalp—but the majority, and the majority closest, are Southern rimsters: Paul Keyes, a California TV producer and frequent visitor to San Clemente; Jack Drowns, a Southern Californian businessman and perhaps Nixon’s oldest friend; Roger Johnson, a lawyer for Superior Oil and old Southern California pal; Billy Graham, the fundamentalist evangelist from North Carolina, now based in Florida; John Connally, the Texas politician who is Nixon’s choice as successor and a trusted friend despite their recent spat that led to Connally’s departure from the White House; Murray Chotiner, the California wheeler-dealer and long-time campaign adviser; and above all, the man to whom Nixon fled after Watergate broke as he has so many times before, Florida real-estate operator and bank owner, Bebe Rebozo.

Nixon’s Top Crony

Rebozo deserves a somewhat closer examination here, for not only is he Nixon’s most intimate associate but he personifies the cowboy type with his disregard for business niceties, his open use of political influence for private gain, his new-money aggressiveness, and his rise to political power.

Rebozo, Cuban-born of American parents, grew up in relative poverty and by the beginning of World War II rose to become the owner of a small gas station in Florida. With the wartime tire shortage, Rebozo got it into his head to expand his properties and start a recapping business, so he got a loan from a friend who happened to be on the local OPA tire board (a clear conflict of interest) and before long was the largest recapper in Florida. Sometime around 1951 he met Richard Nixon, through Florida’s then-Senator George Smathers, who has remained to this day an influential friend of both men, especially in their Southern business dealings, and the two Southern rimsters seem to have hit it off from the start: both the same age, both quiet and humorless, both sports-minded, both aggressive success-hunters. Since that time Rebozo has never lost an opportunity to remind the world of his high-placed friendship.

Rebozo expanded from recapping into land deals and in the early sixties established the Key Biscayne bank, of which he is the president; the first savings account customer, naturally, was Richard M. Nixon. Now it is not known whether Rebozo at this point had any intimate connections with organized crime, but the fact that this bank was used by organized mobsters as the repository for stolen stocks certainly suggests some kind of understanding relationship. In 1968 a group of eight admitted mobsters (people like Jake the Mace Maislich and Joseph Anthony Lamattina) chose Rebozo’s bank as the “launderer” for 900 shares of IBM stock stolen from E.F. Hutton in New York City. Rebozo knew something was fishy about the stocks, apparently, so he phoned Richard Nixon’s brother Donald to ask him about them—though why he thought either Donald or his brother would know about the stolen stocks has never been made clear—and he claims that Donald gave him the OK. Shortly thereafter an insurance circular was sent out to every bank in the country listing the numbers on the stolen certificates and an FBI agent even dropped in at the Key Biscayne bank to inquire about them—and still Rebozo seemed not to realize he was dealing in hot property. Instead he converted the stocks for hard cash, for a friend of his, and has so far gone scot free in the whole affair.

That was neat enough, but Rebozo has other facets. In the sixties Rebozo also managed to get a substantial loan out of the Small Business Administration to build a shopping center in Miami for anti-Castro Cuban businessmen, those Batista men (gusanos is the term used by pro-Castroites) who have neatly become part of the anti-Communist Southern rim in the last dozen years. Now Rebozo, the wealthy banker, was hardly a small businessman, but he did have the advantage of being a close friend of the chief Miami officer of the SBA, who was also, just by coincidence, a stockholder in Rebozo’s bank; somehow, the SBA approved his $100,000 loan for the shopping center. Rebozo also had the advantage of having Nixon as a personal friend, so it hardly mattered to him that Representative Wright Patman, in investigating the loan, accused the SBA of making him a “preferred customer” or that the Long Island newspaper Newsday subsequently denounced the SBA for “wheeling and dealing … on Rebozo’s behalf.” (The full investigation by Newsday was published October 6-13, 1971, and is available from them upon request.)

And would it come now as any surprise that Rebozo chose, for the major contractor on this shopping center job, one “Big Al” Polizzi, a known figure in organized crime, a convicted black marketeer, and a man named by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics as “one of the most influential members of the underworld in the United States?”

And this is the man who shares holidays and weekends with the President, is said to be the only person—obviously excluding Pat—that “the President can really relax with.” Yes, and this is the man the President has even gone in with on real estate ventures, again with the whiff of organized crime around them. Again, one cannot make absolute assertions, for Rebozo and his friends keep things carefully murky: but it is known that a lot of organized crime money went into Florida real estate after it fled Cuba with the downfall of Batista; it is thought that some of this money bought up parcels of land on the southern end of Key Biscayne; it is known that Rebozo and a business partner, Donald Berg, own considerable land holdings in this same area, part of which they have sold to Richard Nixon in an area less than a mile from his Florida White House; and it is known that this same Donald Berg, who has links with at least one associate of mobster Meyer Lansky, has a background so shady that the Secret Service warned Nixon away from eating at his Key Biscayne restaurant for fear of the connections that would be raised in the public mind. Pretty unsavory, to say the very least.

And as for Rebozo’s other business partners? Well, we know of at least one. He is Bernard Barker, a gusano real estate man, one of the major figures for the CIA in the Bay of Pigs operation and the payoff man for the Watergate burglary and other campaign sabotage ventures last year.

With this type of person, of cowboy spirit and Southern interest, in positions of influence, what kinds of national policy can we expect in the immediate future? What kinds of developments should we look for during the rest of the Nixon administration?

First, I think it is highly likely that additional mini-Watergate scandals will emerge. Nixon’s Southern rimsters cannot change their spots overnight, no matter how many cautionary directives come from a chastened White House, and those spots are ingrained with shady dealings and dubious morality. It is hard to see how Roy Ash, who made his way to the top of the corporate ladder at Litton with enough ruthlessness to have involved him in a number of lawsuits, is all of a sudden going to be restrained and decorous in managing the nation’s budget; it’s hard to imagine that he will not carry on high-level variations on his past practices, like the neat little deal he made in 1970 when he dumped some $2.6 million worth of Litton stock just before it became public that Litton’s shipbuilding program was in deep trouble and the price of the stock plummeted by half. Similarly, it is hard to think of Defense Secretary Clements going through an overnight reform, turning his back on such previously profitable schemes as the one in which he suckered the Argentine government into giving his oil company a very profitable franchise through “profound immorality and corruption,” according to the Argentine legislature’s nonpartisan study. These Southerm rimsters are simply incapable of making some of the same kinds of ethical judgments as the rest of us who are not rich wheeler-dealers, and they are almost certain to blunder into one scandal or other sometime in the next three years.

Second, I think we can expect immediate benefits for those industries that are specifically Southern. We have already seen some kindness bestowed on the independent oil producers, both through the granting of hefty 8% rises in heating oil prices in January and the provision in the new budget for underwriting the industry’s new research and “technical assistance” at government expense. In the coming months we are likely to see the opening up of the Eastern seaboard’s continental shelf for off-shore drilling, the ramming through of the Alaska pipeline scheme, the relaxation of all kinds of fuel regulations and restrictions in the name of the largely spurious “energy crisis” (itself fueled by a $3 million industry PR campaign), and a continuing use of tariffs and special benefits to the advantage of domestic producers. The textile industry—especially given the importance of South Carolina in Nixon’s Southern power base—will certainly get the kind of tariff breaks it is looking for, particularly now that the worldwide market has turned around and American firms can be more competitive, Southern agribusiness—sugar, citrus fruits, tobacco, etc.—will also likely be given federal largesse, not only by omission (of price restrictions during the freeze period) but also by commission (of Agriculture Department subsidies and contracts). Defense firms will benefit from the $41 billion increase in the new budget—and this despite the cease-fire in Vietnam and reduction in armed forces—and the kind of reckless what’s-good-for-Lockheed-is-good-for-the-country attitude symbolized by the recent agreement by the US to supply the Third World with biillions of dollars worth of surplus arms.*

Third, I think we can expect Nixonian foreign policy to emphasize the opening up of contacts with heretofore forbidden areas to the benefit of American (and primarily Southern rim) businessmen. We have already seen who benefited from the new Soviet détente: Occidental Petroleum (Los Angeles) is getting the multi-billion dollar oil-and-gas pipeline contract. Brown and Root (Dallas) will build the thing. First City National Bank of Houston will be the primary funder, and John Connally, who is the lawyer for all three concerns, will be considerably richer. This sort of businessman’s détente is sure to increase, both with Russia and China, and I foresee it operating in the Caribbean as well, where so many Southern rimsters have major interests: an arrangement with Cuba allowing increased trade and the introduction of some American interests seems highly likely. As to the Middle East, Nixon has already taken steps to protect American oil interests there—he has chosen Iran as the linchpin, sending in a remarkable number of American troops and a top spook, Richard Helms—and he is likely to expand military aid there, which neatly redounds to the benefit of the defense firms as well as the oil companies.

The news in the morning paper can be confusing: keep in mind, however, that the actions of the Nixon government are likely to serve the interests of the Southern rim, and things become much less mysterious.

Watergate has certainly set back the hopes of the Republican Party, but it still seems possible that, by building on a power base along the Southern rim, it can soon become the majority party in Americna politics for the first time since the 1920s. By appealing to the new-money suburbs through law-and-order rhetoric and revenue sharing largesse, by encouraging defections from the ever-blackening Democratic Party in the South through the hidden racism of anti-bussing and the like, and by serving the interests of the newly powerful economic forces through such policies as I have outlined above, the Republicans stand an excellent chance of solidifying the kind of power they began to enjoy with last year’s landslide election. The defection of John Connally to the Republican Party may be a symbol and a harbinger of a sweeping change.

And the Democratic Party, in response to this slowly tipping seesaw and the possibilities opened up by Watergate, is attempting to regain its position by denying that 1972 ever happened and putting control of the party into the hands of people like Texan Robert Strauss and his new crew of Southern-rim conservatives. It sees its chances for success depending mostly on wooing the conservative Southern-rim vote and crucially on neutralizing the effect of George Wallace by keeping him within Democratic ranks; this accounts for the succession of high-level visitors (recently including Teddy Kennedy) to the Alabamian’s doorstep over the past few months.

So you see, either way, a small part of the South seems to have won. It doesn’t matter whether the banners over the White House are Republican or Democratic so long as the stanchion next to the American Flag in the Oval Office bears the Stars and Bars—or to be more geographically accurate, the Stars and Bars with Lone Star of Texas and the California bear added on. The Southern rim has come to power, and the South, it would seem, has risen again

*So far Nixon has managed to bestow lots of goodies on the defense corporations beyond those open and acknowledged: he permitted a $1 billion arbitrary increase in Lockheed’s prices in 1971 to bail the company out of troubles, and he allowed 131 defense companies to make illegally excessive profits of 30 to 2,000 per cent in 1972 without any government action.

Tags

Kirkpatrick Sale

Kirkpatrick Sale is the author of the just-published book SDS (Random House). His articles have appeared in such newspapers and magazines as the New York Times, The Nation, and The New Leader. He has taught history at the University of Ghana, and is the author of The Land and People of Ghana. (1973)