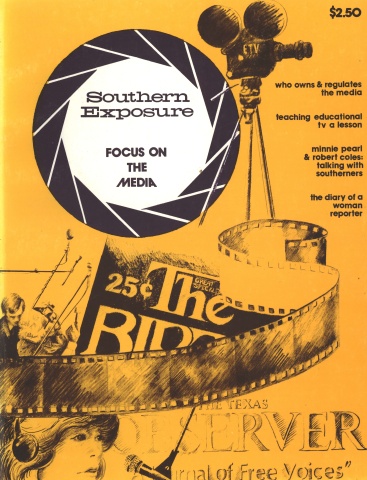

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 2 No. 4, “Focus on the Media.” Find more from that issue here.

Rare, odd moments can tell a lot. I was interviewing Buddy Martin, news-features editor of the St. Petersburg Times, when Nelson Poynter, chairman of the board of the Times Publishing Co., wandered through the newsroom and asked Buddy to check with the weather bureau and find out what the chill factor was today and publish it in tomorrow’s paper. It was a cold, windy day for Florida, but it seemed almost heretical to suggest that the Sunshine State might even have a chill factor, much less print it for the public and tourists to read. Yet, when I think about it, it was the perfect symbolic act ... a flash of honesty that would impress readers and give them a bit of unusual information about their environment. It is this candid attitude that distinguishes the St. Petersburg Times from other newspapers and the reason I had come to Florida to write about their special brand of consumer-oriented journalism and the philosophy that underpins it.

The Times began its consumer journalism a decade ago, I had learned from former editor Donald K. Baldwin, now a professor of communications at the University of South Florida. He attributed the inspiration to consumer advocate Ralph Nader, after their meeting in Washington in 1965. “I thought it was embarrassing that Nader had to put out a book on car safety and that newspapers weren’t reporting that kind of story,” Baldwin recalled in his campus office.

At the time, the Times was planning to remake its women’s page just as the Washington Post brought out its Style section. Baldwin, impressed with the freedom of the Post's model, instituted a similar Day section – devoted to the Home, Lifestyles, Food, Family, Leisure, and Real Estate—and consumer journalism was one of its staples.

In the early Days, Baldwin said, no one was assigned to a consumer beat. Instead, different reporters were recruited to do specific stories and then returned to their regular assignment.

“We also had lots of reporters volunteering to do stories,” the veteran wire service reporter and editor went on. “I created an idea clinic to get participation from the staff in sparking story ideas and they brought in anyone who had an idea, often including outsiders. Most of the consumer stories then came from the idea clinic. We weighed products on carefully adjusted scales and found lots of shortweighting and wrote about it.

“It took a brave man like Poynter to print the kinds of stories that were certain to annoy his friends in business,” he added. Baldwin retired to teach three years ago when current editor Eugene C. Patterson arrived, yet remains close to Poynter and others at the paper.

Patterson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the Atlanta Constitution, who edited the Washington Post and taught at Duke University before coming to the Times, takes no credit for the Times ’ tough consumer approach. “Don Baldwin and Bob Haiman had it rolling before I got here,” he says for openers. “We put a high premium on it, though. Consumer reporting is the most important thing we can do for our readers, many of whom are retired and living on fixed incomes and need to be careful buyers.”

“We ride herd for the public – not play giant killer,” says Patterson, a stocky man with wispy blond ducktails. “Our food price comparison charts, for example, often draw complaints and so each time we run them (monthly in ThursDay’s food section) we try to put a little more information in to explain the list to readers.

“We got one reader who called to tell us you can’t compare apples to apples,” he grinned, “so we invited him to come in because we figured we might learn something from him.”

Since he became the editor and publisher of the Times, Patterson has earned the admiration of his new staff and lived up to his reputation for toughness. Former Times' consumer reporter Joy Hart Hunter relates her favorite Patterson story:

“I once did a price comparison story with a chart showing the prices of 23 non-prescription drugs and cosmetics. Included in the survey were grocery stores, drug stores, dime stores and discount stores. The managers of the discount stores were upset and decided to complain to Patterson. The result was a conference. One manager told Patterson that he did not think newspapers should do that kind of reporting. He had had problems with other papers before, the manager added, but editors always understood his viewpoint after he talked to them. Not too long ago he had talked to the editor of a weekly in Bradenton and the editor had agreed not to do any more consumer reporting, he said.

“With that, Patterson stood up and declared that the St. Petersburg Times is not a weekly in Bradenton, that its editors have different ideas about responsible journalism and asked the managers of the discount stores to leave his office.”

Ms. Hunter, now a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune, says she never felt any pressure to go easy on advertisers. Another story typifies her experience on the Times: “One of the Times' biggest advertisers is Webb’s City, ‘the world’s largest drug store.’ For years Doc Webb has had several full-page ads in almost every edition of the paper. Whenever I did a price comparison, I always included Webb’s City and they certainly didn’t always have the lowest prices. But I was never told to cool it — even though I think the advertising department usually got a call from someone at Webb’s after one of my stories ran.”

Victor Livingston and Michael Marzella, the two Times reporters currently covering the consumer beat, are enthusiastic about the Times and their mission. “This paper has run the gamut of topics, more than any other newspaper in the country,” Livingston began. “We’re now coming back to redo major stories that have been done before. And we’re moving away from strictly factual or dry how-to pieces into a more people-oriented reporting. Our approach has hardened: consumerism is now part of the daily philosophy and content. Consumer stories now appear any time, not just in the TuesDay section.”

“I think the expansion of our coverage has sharpened our outlook and made us more discerning,” Marzella adds. “Consumer journalism must serve as a shopper’s guide and fulfill a watchdog capacity. We have to inform readers on the quality and price of goods and services and the state of the art. Newspapers need to keep an eye on our watchdog agencies. I was shocked to learn several years ago that there are no bacterial standards for ground meat in this country. We need to tell people what they can do about standards . . . who to write. We should take a stand on issues.”

“We act as reviewers and review the work of local agencies in the field of consumer protection,” Livingston goes on. “The agency, combined with newspaper coverage, does put businesses on alert that their performance is being watched. We monitor local agencies and give them plaudits when they function effectively and thumbs down when they don’t.”

“Readers" have to realize that any group with ‘consumer’ in the title doesn’t necessarily mean they’re functioning in their behalf,” Marzella adds. “It may just be serving the ends of business.”

“The net effect of our consumer coverage is to make our readers better buyers,” says Livingston.

“Watch This Space” is a column Marzella began three years ago as a TuesDay feature. To evaluate the accuracy of advertising claims for readers, Marzella conducts a series of tests to examine the claims the product makes. He then writes up the tests and his findings in a short column. For example, in a test of Super-glue, Marzella glued two one-inch square metal surfaces together, one attached to a lifting hook and the other to a load of lead weights. The glue, claiming to support 2000 pounds, gave way under an 800-pound load and Marzella wrote his story.

When Sunoco service stations began their “I can be very friendly” campaign, Marzella visited local Sunoco stations to buy a dollar’s worth of gas and see how much friendly service he got. He found: “No window washings or cleaned mirrors, no battery checks or oil inquiries.” In short, dealers weren’t delivering the service promised in advertising.

Marzella tested Procter & Gamble’s Pampers disposable diapers to see if they kept babies drier than cloth diapers, as their television ads claimed. After several trials, Marzella concluded that Pampers got just as wet as cloth diapers. On a lighter note, Marzella also found that Orville Redenbacker may make the most expensive popping corn (69 cents for 15 ounces) but that it didn’t produce the advertised “one-third more” popped corn than its competitors, thus failing to live up to its claim of superior volume.

Of his innovation, Marzella notes, “I’m not trying to debunk anyone’s advertising. I want to elevate consumers’ consciousness to make them cognizant consumers, aware of what they’re buying. It’s been shown that some advertisers will lie and we want to plant a seed of healthy skepticism about their advertising claims. We’ve never tested a product that doesn’t advertise because we’re testing advertising rather than products. We mostly test television advertising because it’s so visual and its demonstrations are so well-known, but we also test claims of products that advertise in our own paper, magazines and radio ads.

“The reader response is tremendous. I get at least one call a day from readers suggesting ideas for the next ‘Watch This Space.’ But the impact of my story — my 60 lines — on the local community is miniscule compared to the cost of advertising campaigns across the country. We’re not trying to put the screws to anybody, just trying to get the consumer to think a little more about his needs and whether the product advertised is the only one that can fulfill them,” the six-year Times man says.

Livingston, who occasionally does a column, too, cites the limitations of the project. “It would be very difficult for us to replicate very technical tests if products did this. We don’t have the facilities to run such tests. We couldn’t do Jim Dandy dog food because its claim — a graph on growth —defies testing.”

Marzella says he tried to test a Sears Die-Hard battery to see if it would start seven cars as shown on television. After receiving the technical data from Sears, he decided it was too difficult to duplicate the specifications and abandoned the idea.

While some critics have knocked the idea as gimmicky and others insist newspapers ought to test products as well, Marzella and Livingston are satisfied with testing the truthfulness of advertising claims made for products.

“We find many claims to be true, too,” says managing editor Robert Haiman. “We copyright it so we retain control over it and don’t let advertisers use it, even though some agencies have called to try to get permission to do that.”

When the “Watch This Space” feature first appeared, it generated some critical comments from advertisers, including Procter & Gamble. But Advertising Age, the major trade publication of the industry, heralded the innovation. “Not only is it unusual for a newspaper to test ad claims of advertisers—it’s damn gutsy,” said the AA editorial. “It offers a very real service to readers —and isn’t that what a newspaper is all about?”

Perhaps the best testament to the idea is its imitators. Four other newspapers—The Lakeland (Fla.) Ledger, Miami News, Louisville Times, and Vernon (Conn.) Journal-Inquirer — are running similar columns. Of the others, Marzella says modestly, “I’m flattered with the imitations but think much more needs to be done in this area.”

So does former editor Baldwin, who thinks a group of newspapers ought to get together and set up a modest laboratory to do their own product testing, in the manner of Consumers Union. “If a half dozen newspapers each put in $10,000 a year —the cost of one cheap reporter — you could run such a lab. It would work. It could be done. One serving the Southeast, for example, located in Atlanta, would be ideal. The newspapers would get lots of stories out of it for its investment and it would serve the readers and help credibility,” Baldwin concluded.

Despite the fears of losing advertising from such aggressive reporting, Livingston says the Times has lost only one local account and no national advertising from “Watch This Space” reports. “I tested the claims of Audi — that they’d get 24 miles per gallon — and when the model we tested didn’t and we said so, the local dealer withdrew his advertising.”

It was a “Watch This Space” column that led to the Times’ expose of a local advertiser’s illegal practices and an open test of the newspaper’s policy. The story of the expose and its fallout is a landmark in journalism.

In January, 1973, Marzella was checking into one local appliance company’s advertisement when the dealer complained that he was at least selling the merchandise advertised, which is more than his competitor — the Porter Appliance Co. —could claim.

So, Marzella checked the Porter ads and repeatedly tried to buy a TV set for $58 as advertised. Each time, he found it impossible to buy the advertised set and the sales personnel steered him toward higher-priced merchandise. It was a classic bait-and-switch operation which violated Florida consumer protection laws.

After Marzella’s article exposing the firm’s practices appeared, store owner Edwin “Po’ Boy” Porter said the violations were unintentional and caused by overzealous salesmen he planned to fire.

Several months later, a former assistant manager of Porter’s store in Lakeland called the newspaper to reveal more of the Porter sales technique. He told the Times about Porter’s 14-page sales course which instructed new salesmen on how to sell to different types of buyers - the Redneck, the Black Boy, the Jewish Buyer and the Sharp Young Buyer. (See selling tips in enclosed box.) The ex-employee drew up an affidavit affirming his story and even submitted a memo written by Porter that began: “Bate [sic] and switch is the American way.”

When reporter Joy Hart Hunter confronted Porter with the story, he admitted that the sales techniques were his.

With that, the story was shown to publisher John B. Lake who announced that the Times and its sister paper, the Evening Independent, would no longer accept advertising from Porter. That decision cost the newspapers nearly $237,000 in lost revenues.

Not long after the expose and cancellation of the advertising, the Porter Appliance Company was nabbed by the Internal Revenue Service for failing to file withholding tax for its employees. The compounded troubles forced Porter to go out of business.

“We decided we could probably expose several other big advertisers and cancel their advertising, too,” recalled Ms. Hunter. “But we wondered how far we could go without defeating our purpose. It wasn’t really our job to enforce the state’s bait-and-switch law. We felt the Porter story had been an effective way of informing the public about the problem.”

Editor Patterson was terse about the episode: “We bruised our nose with lost revenue, but we had to do it.”

“Our name has been used by others to get people to reform their practices,” Livingston says of the paper’s reputation. “Businesses are told if they don’t change they will be reported to the Times. ”

“We have to be careful not to tell people that we’re from the Times so we don’t get special favors and get into conflict of interest situations,” Marzella added. “Our staff gets no discounts or freebies, which probably helps improve our credibility.”

“I try to do all my business as an average consumer,” Livingston continues. “I use these experiences as part of my work.”

Marzella is quick to admit. “We’re no more immune to being ripped off than anyone.”

“But we know the steps to take and should be more effective,” counters Livingston. “Generally, when laymen are up against professionals, consumers are the ones that are out to lunch.”

“You never stop being a consumer reporter,” Marzella says. “When I go grocery shopping, I find myself reading the temperatures in the refrigeration cases and noting that it’s 40 degrees.”

Supermarket sanitary conditions are another of Marzella’s reporting interests. He began writing about supermarkets in October, 1972, when he accompanied a health inspector on his regular rounds and reported every nitty gritty violation: decaying meat scraps on a machine in the meat cutting room, filthy floors, dirty food cases, thawed and refrozen juice that should have been condemned. He also told readers to check up on their supermarket and report violations. In that first survey, Marzella found 13 of 14 Pinellas County supermarkets surveyed to have sanitation violations.

In July, 1974, Marzella did a follow-up survey and reported: “We found more supermarkets and more people, but fewer inspectors. Conditions hadn’t improved. Many violations were the same; most were in meat departments and in refrigeration and were caused by gross neglect.”

The Times ran Marzella’s reports for five consecutive days on the front page of the Day sections. The inspector’s complete reports for each store were printed in full and in the case of the 28-store Publix chain, the report covered 65 column inches of space. Although the cold, descriptive language of the inspectors was used, the report made for exciting if upsetting reading. Such horrors as moldy sausage on display and rat droppings in the meat room were recounted. Of the 83 stores inspected, only five got a clean bill of health.

Interest in clean supermarkets prompted the Times to join in a national meat test conducted in seven cities in November, 1973, by Media & Consumer, an independent publication that monitors consumer affairs in the press. The project involved visiting 20 different St. Petersburg supermarkets of the six major chains and buying hamburger on display and whisking it to a laboratory for extensive tests.

All 20 hamburger samples were shown to have high bacteria content, including E. Coli or fecal bacteria, a known disease-causing organism. One sample, from Kash and Karry, contained more than 3,000,000 bacteria per gram. The Publix stores were singled out for their overall high counts. In all, only four of the samples — all from A & P — were considered acceptable and seven were considered putrifying.

For their participation in the meat test, Media & Consumer commended the Times and the others for their commitment “to putting their readers’ interests above everything else.”

Victor Livingston, who has been at the Times for nearly a year after graduating from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, also exhibits a personalized, every-reader quality in his writing. Recently, for example, he wrote about how to decode a General Telephone Co. bill and compared the consumer information on sample local bills with those of Southern Bell (and found them better) and with those of New Jersey Bell (and found them deficient).

Just before Christmas, he conducted “The Great Interstate Parcel Package Derby” and sent six identical one-pound packages to Wilmington, Del., his hometown, to measure the efficiency and economy of service. His findings were graphically illustrated with Mr. Zip of the U.S. Post Office in first place with a three-day elapsed time from mailing to delivery. Cost: $1.16. REA Surface Express brought up the rear, arriving after seven days. Cost: $23.71.

“Part of the Day section philosophy is to react to the news,” Livingston says. “Newspapers can’t be encyclopedic or tell everything about everything. For example, the Times is weak in its environmental coverage because no one is assigned to this important area.”

Managing editor Haiman delights in describing how consumer journalism has permeated the entire staff and their writing. “After the Betty Ford and Happy Rockefeller operations, we were interested in telling our female readers how to check themselves for breast cancer. So we hired a model and a female gynecologist and took a series of photographs — showing full breasts and nipples—demonstrating the examination. The pictures appeared in color on the front page of the SunDay

Family section and we had lots of positive response and no complaints. We didn’t want to use the diagrams the A.P. moved and thought the public was ready for this kind of coverage.”

Food editor Ruth Gray earns Haiman’s respect with her full-fledged professionalism. Ms. Gray writes zingy restaurant reviews, carries Dr. Jean Mayer’s nutrition column, assembles the food price comparison charts, and writes features on such timely subjects as sugar substitutes and economy meals. Unlike other food editors across the country, she refuses to publish the public relations handouts and recipes that food companies send out and politely sends back all gifts from food manufacturers.

“We have the toughest conflict of interest policy of any newspaper in the country,” boasts Haiman. “We don’t accept anything from anyone!” The Times even refuses to accept review copies for books, preferring to buy the books they have a special interest in reviewing.

Haiman gives his staff full credit for their accomplishments. After the Times gave reporter Jane Daugherty a leave of absence and a scholarship to study gerontology, she returned to begin an investigation of local nursing homes. Not only did her series help readers with their selection of homes, but it also contributed to a shake-up in the state Department of Aging. Later, a blue-ribbon investigating committee authenticated most of her conclusions about the appalling conditions: filthy rooms and kitchens, rats, roaches and other pests, lack of proper medical care, shortage of skilled staff, high patient maintenance costs, unjust legal procedures, and lack of alternative services which could help an aged person continue living in his own home.

Real estate editor Mrs. Elizabeth Whitney has written some remarkable articles about Florida’s swamp peddlers and real estate swindles. She also uncovered traces of Mafia links to land sales operations here.

But Mrs. Whitney’s most widely heralded story dealt with the International Telephone & Telegraph Co.’s new Palm Coast development, billed as “the world’s largest subdivision.” When ITT slated a press junket to announce its new northeast Florida “city” the Times sent Mrs. Whitney at the newspaper’s expense. Several hundred other invited journalists freeloaded. Skeptical of the serious ecological and economic problems that were about to be spawned by a new community of 650,000 in an area that now has a population of less than 5,000, she wrote:

“Thousands and thousands of little investors will spend hundreds of millions of dollars on overpriced, poorly drained Palm Coast land because they have been convinced they will make a ‘killing’ in Florida real estate. A ‘killing’ will be made, but it will be by ITT, not the little people who go to dinner parties and buy lots priced from $3,600 to $26,000 for land bought for about $300 an acre.”

All of the junketing journalists, except Mrs. Whitney, cranked out obsequious stories and commentaries on the splendors of Palm Coast, many of them quoting extensively from the ITT-prepared press releases. Mrs. Whitney also took the press to task with a story headlined: “Junkets Lure Media to Sing For Supper.” In that story, she described the elaborate weekend of wining, dining and recreation which cost ITT some $20,000, and the other tactics the ITT press relations people used attempting to get press coverage. “Her stories were honest assessments of Palm Coast and at the same time raised questions about press performance and attempted to raise standards by reporting excesses,” Haiman reflected.

“Consumer reporting is a survival kit,” he said. “We have to provide information that will help people make it through.”

The best example of this philosophy in practice is the two-part SunDay section published in late September called “Focus on Inflation.” The stories centered on coping with a changing economy with features on the Depression years, safeguards to prevent the recurrences of the 1930s deprivations, parallels between 1929 and 1974, how the poor cope with limited budgets, plus inflation-fighting tips and budget management.

Marzella also did a series on lifestyles of family budgets, which included, in the event of a depression, the area’s priorities for WPA projects.

Critics of the arts also write critically. One film critic recently reported how a film that was X-rated in their newspaper ad had cut all the segments showing explicit sex and turned it into an “R” film without informing customers. Hard-core fans were being duped, the critic wrote.

Film reviews also carry a summary at the end to alert the reader about its content. A sample mini-review read: “The Groove Tube does indeed contain sex, nudity, profanity and violence, and each for its own unadulterated sake.” Appropriate symbols denote each characteristic.

Music critic Mary Nic Shenk went to a local nightclub to hear pianist Jan August, who was billed there. When she heard the wretched performance, she suspected the pianist was an impostor and threatened to expose him. The nightclub owner changed the name of the performer in the following day’s ad.

Newsfeatures editor Martin says of the Times reviewing policy, “Our reviews should tell our readers whether they should or shouldn’t go. We have no no-no’s here. Our only guideline is ‘be fair.’ ”

Even the sports staff has been slightly infected with consumerism and has taste-tested the food and complained about the price of drinks (Cokes are 75 cents) at the local stadium.

Investigative reporting is the other related area of journalism in which the Times flexes its independence in the name of public service. Patterson is proud of the newspaper’s 1974 record: reporting that led to indictments of three state cabinet officers and that found two State Supreme Court justices guilty of impropriety. “For volume, we’re ahead of the Miami Herald in good investigative reporting, though their work on Senator [Edward J.] Gurney was impressive,” Patterson says. (During its 90 years, the Times has garnered an impressive number of state and national awards — some 900 in all — including a Pulitzer Prize in 1964.)

Aggressive reporting occasionally results in legal hassles, which the paper is prepared for. Currently they are appealing an 8-month jail sentence handed down to reporter Lucy Ware Morgan for refusing to reveal her confidential sources in a leaked story about a secret grand jury presentment concerning police improprieties.

Never knuckle under or settle is the Times’ policy. “Be fair. Apologize in print. Make corrections as prominent as the original. But if sued, we fight. We don’t settle and this stance gives us a reputation,” Patterson said. He insists lawyers should only give advice or a word of caution to editors, not make policy. “You want the lawyers to tell you what they think about what you’re going to do and then you have to make that lonesome decision, just as Katherine Graham of the Washington Post did on running the Pentagon Papers against all advice of counsel.”

Patterson and Haiman cite Mr. Poynter’s four point priority list, when it comes to making decisions or resolving conflicts. His order of priority of consideration puts the reader first, then advertisers and staff, and, finally, the stockholders (Poynter and his family who own both papers outright).

Haiman is eloquent about the newspaper’s editorial posture. “People must not give up on the system. They must fight city hall. They aren’t impotent. The press is part of participatory democracy.

“We never fail to endorse candidates for election as some newspapers do. Newspapers do have special expertise after interviewing each candidate with the same questions. We have an obligation to choose one candidate over the other because one of them will win.

“Putting out a liberal democratic newspaper in a conservative Republican city is an interesting exercise,” he says with a grin. “We run a pro-con editorial page that helps disarm those who are against us — that know-nothing opposition. We run all arguments in favor of an issue down one side of the page, all those against the issue down the other, our editorial position in the middle and a coupon at the bottom of the page asking readers to send us their views. We also allow staff members to express dissenting opinions on the editorial page and occasionally have a taker. In all, it’s an attempt to get readers to participate. I think it’s also made our editorial page more persuasive and that’s what the page is supposed to do.”

Like other businessmen, Patterson is currently concerned with rising costs. The cost of newsprint, obviously a major item, has nearly doubled in a year. One small economy measure that most readers won’t even notice, but that will save nearly $250,000 annually is reducing the page size by one-fourth of an inch. Advertising rates are expected to go up, shrinking the number of pages, though increasing revenue. “Most readers already think our monster papers on Thursday and Sunday are too big,” Patterson says. “You make a bad mistake, though, if you take all the economy steps by just shrinking the news hole.

“Costs will reduce the size of all American newspapers and overall that will be good. It will be more of a challenge to write news briefly and be more direct. Better editing is the key. We’ll have to boil some stories down to get space for significant stories.”

Another austerity move that Patterson authorized in September was a “streamlining” of the staff or laying off of 120 employees in all departments—most were production people who were “double staffing” in the changeover to offset printing from letterpress. About 20 editorial employees were dismissed, leaving the staff at 205.

“Our profit picture was sliding and 1975 looked uncertain,” Patterson explained. “So we cut staff and tightened our belts but didn’t give up anything. We plan to bring in cathode ray tube outlets into the newsroom that will be on-line with typesetting computers and this technology will represent a tremendous saving in production as well as give the news department more control.”

The layoffs have affected employee morale and renewed some talk of organizing a union (the Newspaper Guild), a move opposed by management. Haiman dismisses the action by citing only 21 signatures to an exploratory letter and stating, “We’re a pro-labor paper with a tradition of dealing humanistically with the staff on a one-to-one basis and that relationship would suffer if we introduced a third party.”

Grumbles about low salaries recently led to a new pay scale, which Patterson made a priority. “We make no apologies to anyone for our salaries and other employee benefits such as the profit-sharing plan and cost of living supplements over merit raises,” Haiman notes.

In addition to local news staff, the paper has a one-man bureau in Washington, two in Tallahassee and several dozen reporters in surrounding counties covered by four regional supplements.

The paper also uses a judicious selection of national and world news from the Associated Press and United Press International and a host of newsfeatures from The New York Times News Service and the Washington Post-Los Angeles Times News Service.

The Times maintains a nearly “ideal” advertising to news ratio —60 to 40 per cent —for both profitability and service. Circulation, which fluctuates with the tourist season, is about 186,000. The paper’s total revenue for 1974 is expected to be $45 million, up some $4.5 million from the year before.

No doubt Patterson could wring out larger profits if he would be satisfied with less quality. “The owner is committed to making this the model American newspaper, so we innovate. I consider it an experimental newspaper,” he says with satisfaction.

Tags

John W. English

John English teaches magazine and critical writing at the University of Georgia School of Journalism and is finishing a book on Critics of the Popular Arts. (1975)